По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

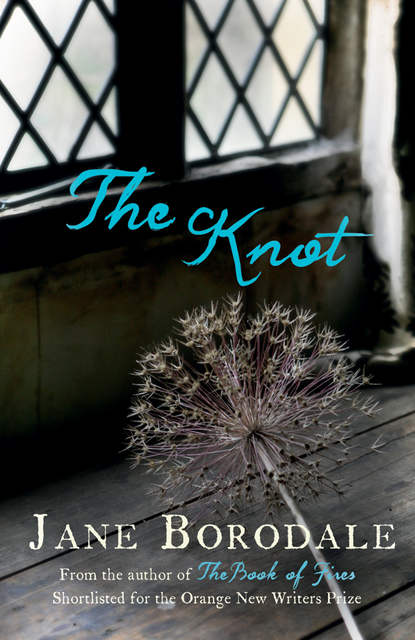

The Knot

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It is almost All Souls’, he thinks, as he goes back to his study to note down the last of his financial outgoings before the end of the month. October has flown by. There is little of note for the rest of the afternoon, bar a brief flurry of noise from the other side of the house when in the kitchen one of the servants scalds her hand on a kettle, and then the boy comes with the packhorse for his father’s grain. Henry Lyte has to pay his father two bushels each of wheat and dredge malt every week to supply their household brewing and bread over at Sherborne. Sometimes he wishes that they would take a fortnight’s worth at once, or more, and leave him in peace. His stepmother Joan Young (he will not call her Lyte, nor mother; she is no blood of his) declares that there is no provision for storage at their house, but Henry knows it is an excuse to keep a weekly eye on proceedings at Lytes Cary. She is becoming far too interested in it.

After this he is able to be utterly absorbed in his accounts. Henry puts aside what he needs to pay the tithingman of Kingsdon for the queensilver, which is sixteen shillings the quarter, and works out what he is owed himself on the field rents since Lammas. These accounts done, he is free to return to his work on the herbal.

As a grey evening draws in again, earlier and earlier now it is so close to Hallowtide, there is an interruptive, particular tap on his door that has become familiar to him this last fortnight, and Frances comes into the room.

‘You have not lit the candle yet, Henry,’ she says.

‘I can see well enough.’

‘They have been calling supper.’ She sounds annoyed, but goes to her husband’s side and touches him lightly on the shoulder. He puts down his pen and a sentence hangs unfinished; Medewort doubtlesse drieth much, and is astringent, wherefore it restraineth and bindeth … the word manifestly floats newly inked, untethered to any other on the page. It can’t be helped. Her fingers are indeed very pale and smooth. What she lacks in warmth of speech, he has decided, she makes up for in other ways. Her presence glitters softly out of the corner of his eye as she picks up a pebble on his desk and turns in the gloom towards the light to examine it idly, puts it down again. She smells of subtle things, something like damask rose perhaps or musk ambrette, a dusky, milky scent that he presumes she must buy from a London perfumier in a bottle, though he likes to think it is her skin itself that secretes such promise, such difference from what he is.

He has a sudden thought of her fingers as they would be if closing round his own, against his limbs. He finds that he understands her with more clarity once the matters of the day are over. He likes the silences produced at night – the dwindling need for words and explanations. A silence lit by daylight has to be used fully, taken advantage of, but at night a silence could be simply encountered, dwelt in, quite for its own sake. He wishes that on balance it might not be unreasonable to dispense with supper altogether and suggest the bedchamber. Of course it would be very unreasonable, but he admits her presence excites his senses, distracts him.

When he lies with her at night, she does not envelop him as Anys used to, with gentle arms and her eyes appreciatively closed. Frances keeps her eyes open and fixes him with a gaze that he cannot read or enter into. He thinks it is curiosity that makes her do this, but he can’t be sure. Her body is very different from Anys’s, too, more taut, rawboned. She does not seem to object to him paying her proper attention in bed; indeed, more than once he has had the distinct sense this gives her a gleam in her eye, but again it is hard to be sure. His father always told him that whores are the only women who enjoy their carnal duties to the husband, and he would not like to think badly of her. For himself of course he prefers to think of it as natural procreation rather than venery.

‘But what will you do with all this effort, this … learning, Henry?’ she asks unexpectedly, as if puzzled. She has never asked a thing about his work before.

‘Do you mean my book?’ He lets her wrist go and begins to gather up the pages that are dry into a bundle.

‘I mean the book, the time in the study, those letters that come, the exertion generally.’ He can’t see her expression.

‘I don’t have a publisher yet for my translation, but I have high hopes. My dear,’ he adds briskly, as she stifles a yawn. ‘Is it late? Is it white herring for supper again? No doubt it can’t be helped, on a Friday. When a thing is plentiful there is always so much of it.’ He wonders why his habit is to speak so loudly when he talks to her.

‘Could we go up to London before Christmas?’ she asks.

‘London? Certainly not. There is too much to do. The roads are a nightmare.’

Neither speaks for a moment. Outside by the gate a dog is barking. A dog barking at dusk always sounds louder, he thinks, than during the day. A log slips on the fire irons, and a shower of sparks flies up the chimney.

‘Why do you suppose that old woman never does her work indoors?’ Frances asks.

‘What woman?’

‘Whom you spoke to this morning, the old basketmaker.’

Henry frowns. ‘What makes you mention that?’

‘I’ve been watching from the bedchamber window, she sits out there all day.’

‘Perhaps her rafters are too low – those rods of willow reach very tall at the beginning of a basket. And you will have seen how they take up room to the sides as she weaves, her cottage must be too cramped for such activity.’

‘Or perhaps she needs the brighter daylight to properly see what she is doing.’

‘She is blind. Her eyelids have been sewn shut for nearly thirty years.’

‘Oh!’ Frances flinches at the thought.

There is a silence. Really he’d prefer to start a new page of his translation, but he cannot do it with Frances standing by him. He cuts a nib for later. He might get up to fleabane by tomorrow. Hote and dry in the third degree. It is going to take him ten years or more at this rate.

‘How did she become blind?’ Frances asks.

‘Mmm?’

‘The old woman.’

‘I’ve no idea.’ There is something vaguely tugging at his memory as he says that, something odd and unpleasant from way back when he was a boy, but then it is gone. He does remember the talk around the time that they sewed her lids shut to cover up the mutilation.

‘I was away at school but they said her screeching was heard right down on the Fosse Way. After that when I was disobedient I thought that the redness I saw when I shut my eyes was God showing me the colour of blood, a warning not to cast my gaze unheedingly upon wicked things. I always thought she must have seen some wicked thing to get like that.’ He shrugs, looking at his manuscript. ‘The savage, unfair minds of children.’

‘I can’t imagine a noise like that coming from her.’ Frances is still at the window.

‘She’s got a stone’s silence about her most days. Squatting there in the middle of her webs, though like most old women she can also pounce on a man with unsolicited speeches, if he should forget to go by the other path. How she knows who it is that’s passing is any man’s guess, but she always does.’

Once a month Henry sees Widow Hodges at the market in Somerton, selling her baskets. He’s seen her struggling up onto the cart pulled by a decrepit skewbald that another old woman, with whom she shares profits, drives over from Kingsdon. Years ago, he used to see her plying her wares further afield, such as the St Paul’s Day Fair at Bristol, but she is too old now for such distances.

‘Maybe she does need the light to work by. I’ve heard some can see the brightness of the sun. There are degrees of blindness, Henry. Many different kinds.’

‘There are many different kinds of spider.’

He thinks of her as sat at the heart of a web. He can’t help it. Even though she is blind, when he goes by her cottage he has a suspicion that she has an inward eye on him, some kind of sentient finger or whisker stretched out to feel the twitch of his passing. There is something about the way she cocks her head as he approaches that makes him shiver, without a pause in the rhythm of her fingers catching the withies, knotting them down, netting his details.

Chapter V.

Of MOUSE EARE. A man may finde amongst the writers of the Egyptians, that if a bodie be rubbed in the morning early, before he hath spoken, at the first entrance of the moneth of August with this hearbe, that all the next yéere he shall not be grieved with bleared or sore eyes.

HENRY LYTE HAS GONE OVER TO WELLS to buy various items. He wants to go himself rather than send a servant, for he has heard that his old friend Peter Turner is in town staying with his father – the radical Dean of Wells Cathedral, and botanist of note, Dr William Turner. The ride over is back-endish, yellowing stalks collapsing over the paths, the sweet smell of fruit and rot everywhere, too many insects. He is glad that he still has the Turners to discuss matters of botany with. Another good friend Thomas Penny – in whom he had a fellow fieldworker, together scouring the West Country and elsewhere thoroughly for plant specimens – has just gone to Zurich because Archbishop Parker believes him to be too outspoken against the church. Dr Turner is outspoken too, but somehow retains his position here as Dean of the cathedral since his return from exile in Germany during the dark time of Mary. ‘So far, so good,’ he’d grinned the last time he’d seen him, as though it was all a conspiracy, or luck.

As Henry winds through the busy, dirty marketplace, the booths, the standings, flesh shambles and fish shambles, towards the cathedral, the clock strikes ten and he realizes he’s going to be too early. He scratches his beard, which feels itchy and unkempt, and decides to go to the barber for a trim. He dismounts and turns his horse around. The sky to the west is dark with impending rain, though the sun is out, so that the stone of Penniless Porch shines yellow by contrast. A beggar is lying inside the arch, his face blotched with sores and clutching his stomach as if he had some griping torment there. Henry hopes it is not dysentery. A woman passing by grimaces at her companion.

‘Look at that, poor man, he is in pain,’ she says.

‘But they are used to being like that. Quite accustomed. I need to get a pigeon before we go back. Or two. Do you think we need two?’ She checks in her basket then looks down at the beggar. ‘It is different for them. They don’t know any better, just as well. They are like animals in that respect.’

‘It is a shame.’

‘One must pray for them,’ she says brightly. ‘There is nothing else anyone can do about it.’

‘Nothing,’ the other woman concurs, and they glide on towards the market and the pigeon stall. Henry feels the blood rushing in his ears. He has an urge to run after them and try to make them see how they are wrong, but instead goes swiftly to the beggar and on the same, furious impulse gives him the first coin that he fishes from his pouch, which is a half-sovereign, a great amount of money to give to any man in the street or otherwise, more than a skilled mason earns in a week. The beggar’s eyes widen, and even as he puts it into the outstretched bandaged, filthy hands Henry has a spasm of doubt, but it is too late.

‘Bless you, Master, it is a sign!’ The beggar mutters, rubbing the coin against his cracked lips. He jerks a finger at the sky, and to the west now a rainbow is stretched inkily over the whole of the town, so vivid with colour it almost fizzes in the sky. He must be right. Surely this must be a good omen.

Fat drops of rain begin to spot the dry compacted earth of the thoroughfare as the sunshine fades. People jostle to take shelter under the porch, and when he turns about, the beggar has vanished.

Half a sovereign.

He had better not mention that to anyone, not Frances, not Dr Turner, he decides. But by the time he has arrived at the house, it is already weighing so heavily upon him that he must say something. The boy removes his horse to the livery and another poor man follows him up to the gate and pulls at his sleeve most insistently until he finds a coin to make him go away. He is more careful this time, makes sure it is a penny.

Turner’s naughty little dog comes to greet him, yapping at his heels. Turner has trained it to jump up and remove the corner-caps of bishops at table. Turner hates ecclesiastical trappings; the pomp and ceremony of the high church. He also hates his bishop, which is making life difficult in Wells, but Turner has always prided himself on his ability to thrive on controversy.