По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

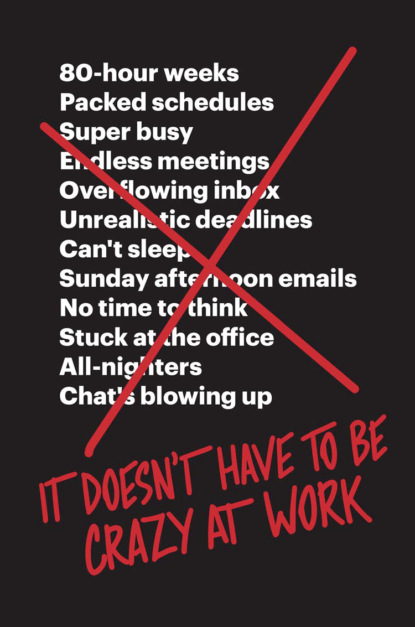

It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

For some that may seem shortsighted. They’d be right. We’re literally looking at what’s in front of us, not at everything we could possibly imagine.

Short-term planning has gotten a bum rap, but we think it’s undeserved. Every six weeks or so, we decide what we’ll be working on next. And that’s the only plan we have. Anything further out is considered a “maybe, we’ll see.”

When you stick with planning for the short term, you get to change your mind often. And that’s a huge relief! This eliminates the pressure for perfect planning and all the stress that comes with it. We simply believe that you’re better off steering the ship with a thousand little inputs as you go rather than a few grand sweeping movements made way ahead of time.

Furthermore, long-term planning instills a false sense of security. The sooner you admit you have no idea what the world will look like in five years, three years, or even one year, the sooner you’ll be able to move forward without the fear of making the wrong big decision years in advance. Nothing looms when you don’t make predictions.

Much corporate anxiety comes from the realization that the company has been doing the wrong thing, but it’s too late to change direction because of the “Plan.” “We’ve got to see it through!” Seeing a bad idea through just because at one point it sounded like a good idea is a tragic waste of energy and talent.

The further away you are from something, the fuzzier it becomes. The future is a major abstraction, riddled with a million vibrating variables you can’t control. The best information you’ll ever have about a decision is at the moment of execution. We wait for those moments to make a call.

Comfy’s cool

The idea that you have to constantly push yourself out of your comfort zone is the kind of supposedly self-evident nonsense you’ll often find in corporate manifestos. That unless you’re uncomfortable with what you’re doing, you’re not trying hard enough, not pushing hard enough. What?

Requiring discomfort—or pain—to make progress is faulty logic. NO PAIN, NO GAIN! looks good on a poster at the gym, but work and working out aren’t the same. And, frankly, you don’t need to hurt yourself to get healthier, either.

Sure, sometimes we stand at the threshold of a breakthrough, and taking the last few steps can be temporarily uncomfortable or, yes, even painful. But this is the exception, not the rule.

Generally speaking, the notion of having to break out of something to reach the next level doesn’t jibe with us. Oftentimes it’s not breaking out, but diving in, digging deeper, staying in your rabbit hole that brings the biggest gains. Depth, not breadth, is where mastery is often found.

Most of the time, if you’re uncomfortable with something, it’s because it isn’t right. Discomfort is the human response to a questionable or bad situation, whether that’s working long hours with no end in sight, exaggerating your business numbers to impress investors, or selling intimate user data to advertisers. If you get into the habit of suppressing all discomfort, you’re going to lose yourself, your manners, and your morals.

On the contrary, if you listen to your discomfort and back off from what’s causing it, you’re more likely to find the right path. We’ve been in that place many times over the years at Basecamp.

It was the discomfort of knowing two people doing the same work at the same level were being paid differently that led us to reform how we set salaries. That’s how we ended up throwing out individual negotiations and differences in pay, and going with a simpler system.

It was how uncomfortable it felt working for other people at companies that had taken large amounts of venture capital that kept us on the path of profitable independence at Basecamp.

Being comfortable in your zone is essential to being calm.

Defend Your Time

8’s enough, 40’s plenty

Working 40 hours a week is plenty. Plenty of time to do great work, plenty of time to be competitive, plenty of time to get the important stuff done.

So that’s how long we work at Basecamp. No more. Less is often fine, too. During the summer, we even take Fridays off and still get plenty of good stuff done in just 32 hours.

No all-nighters, no weekends, no “We’re in a crunch so we’ve got to pull 70 or 80 hours this week.” Nope.

Those 40-hour weeks are made of 8-hour days. And 8 hours is actually a long time. It takes about 8 hours to fly direct from Chicago to London. Ever been on a transatlantic flight like that? It’s a long flight! You think it’s almost over, but you check the time and there’s still 3 hours left.

Every day your workday is like flying from Chicago to London. But why does the flight feel longer than your time in the office? It’s because the flight is uninterrupted, continuous time. It feels long because it is long!

Your time in the office feels shorter because it’s sliced up into a dozen smaller bits. Most people don’t actually have 8 hours a day to work, they have a couple of hours. The rest of the day is stolen from them by meetings, conference calls, and other distractions. So while you may be at the office for 8 hours, it feels more like just a few.

Now you may think cramming all that stuff into 8-hour days and a 40-hour week would be stressful. It’s not. Because we don’t cram. We don’t rush. We don’t stuff. We work at a relaxed, sustainable pace. And what doesn’t get done in 40 hours by Friday at 5 picks up again Monday morning at 9.

If you can’t fit everything you want to do within 40 hours per week, you need to get better at picking what to do, not work longer hours. Most of what we think we have to do, we don’t have to do at all. It’s a choice, and often it’s a poor one.

When you cut out what’s unnecessary, you’re left with what you need. And all you need is 8 hours a day for about 5 days a week.

Protectionism

Companies love to protect.

They protect their brand with trademarks and lawsuits. They protect their data and trade secrets with rules, policies, and NDAs. They protect their money with budgets, CFOs, and investments.

They guard so many things, but all too often they fail to protect what’s both most vulnerable and most precious: their employees’ time and attention.

Companies spend their employees’ time and attention as if there were an infinite supply of both. As if they cost nothing. Yet employees’ time and attention are among the scarcest resources we have.

At Basecamp, we see it as our top responsibility to protect our employees’ time and attention. You can’t expect people to do great work if they don’t have a full day’s attention to devote to it. Partial attention is barely attention at all.

For example, we don’t have status meetings at Basecamp. We all know these meetings—one person talks for a bit and shares some plans, then the next person does the same thing. They’re a waste of time. Why? While it seems efficient to get everyone together at the same time, it isn’t. It’s costly, too. Eight people in a room for an hour doesn’t cost one hour, it costs eight hours.

Instead, we ask people to write updates daily or weekly on Basecamp for others to read when they have a free moment. This saves dozens of hours a week and affords people larger blocks of uninterrupted time. Meetings tend to break time into “before” and “after.” Get rid of those meetings and people suddenly have a good stretch of time to immerse themselves in their work.

Time and attention are best spent in large bills, if you will, not spare coins and small change. Enough to buy those big chunks of time to do that wonderful, thorough job you’re expected to do. When you don’t get that, you have to scrounge for focused time, forced to squeeze project work in between all the other nonessential, yet mandated, things you’re expected to do every day.

It’s no wonder people are coming up short and are working longer hours, late nights, and weekends to make it up. Where else can they find the uninterrupted time? It’s sad to think that some people crave a commute because it’s the only time during the day they have to themselves.

So, fine, be a protectionist, but remember to protect what matters most.

The quality of an hour

There are lots of ways to slice 60 minutes.

1 × 60 = 60

2 × 30 = 60

4 × 15 = 60

25 + 10 + 5 + 15 + 5 = 60

All of the above equal 60, but they’re different kinds of hours entirely. The number might be the same, but the quality isn’t. The quality hour we’re after is 1 × 60.

A fractured hour isn’t really an hour—it’s a mess of minutes. It’s really hard to get anything meaningful done with such crummy input. A quality hour is 1 × 60, not 4 × 15. A quality day is at least 4 × 60, not 4 × 15 × 4.

It’s hard to be effective with fractured hours, but it’s easy to be stressed out: 25 minutes on a phone call, then 10 minutes with a colleague who taps you on the shoulder, then 5 on this thing you’re supposed to be working on, before another 15 are burned on a conversation you got pulled into that really didn’t require your attention. Then you’re left with 5 more to do what you wanted to do. No wonder people who work like that can be short- or ill-tempered.

And between all those context switches and attempts at multitasking, you have to add buffer time. Time for your head to leave the last thing and get into the next thing. This is how you end up thinking “What did I actually do today?” when the clock turns to five and you supposedly spent eight hours at the office. You know you were there, but the hours had no weight, so they slipped away with nothing to show.

Look at your hours. If they’re a bunch of fractions, who or what is doing the division? Are others distracting you or are you distracting yourself? What can you change? How many things are you working on in a given hour? One thing at a time doesn’t mean one thing, then another thing, then another thing in quick succession; it means one big thing for hours at a time or, better yet, a whole day.

Ask yourself: When was the last time you had three or even four completely uninterrupted hours to yourself and your work? When we recently asked a crowd of 600 people at a conference that question, barely 30 hands went up. Would yours have?