По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

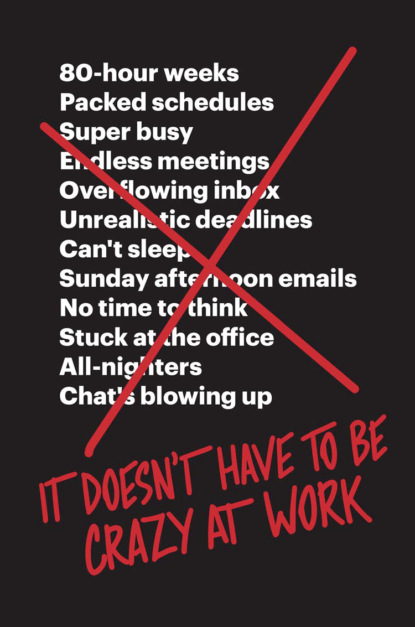

It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Effective > Productive

Everyone’s talking about hacking productivity these days. There’s an endless stream of methodologies and tools promising to make you more productive. But more productive at what?

Productivity is for machines, not for people. There’s nothing meaningful about packing some number of work units into some amount of time or squeezing more into less.

Machines can work 24/7, humans can’t.

When people focus on productivity, they end up focusing on being busy. Filling every moment with something to do. And there’s always more to do!

We don’t believe in busyness at Basecamp. We believe in effectiveness. How little can we do? How much can we cut out? Instead of adding to-dos, we add to-don’ts.

Being productive is about occupying your time—filling your schedule to the brim and getting as much done as you can. Being effective is about finding more of your time unoccupied and open for other things besides work. Time for leisure, time for family and friends. Or time for doing absolutely nothing.

Yes, it’s perfectly okay to have nothing to do. Or, better yet, nothing worth doing. If you’ve only got three hours of work to do on a given day, then stop. Don’t fill your day with five more just to stay busy or feel productive. Not doing something that isn’t worth doing is a wonderful way to spend your time.

The outwork myth

You can’t outwork the whole world. There’s always going to be someone somewhere willing to work as hard as you. Someone just as hungry. Or hungrier.

Assuming you can work harder and longer than someone else is giving yourself too much credit for your effort and not enough for theirs. Putting in 1,001 hours to someone else’s 1,000 isn’t going to tip the scale in your favor.

What’s worse is when management holds up certain people as having a great “work ethic” because they’re always around, always available, always working. That’s a terrible example of a work ethic and a great example of someone who’s overworked.

A great work ethic isn’t about working whenever you’re called upon. It’s about doing what you say you’re going to do, putting in a fair day’s work, respecting the work, respecting the customer, respecting coworkers, not wasting time, not creating unnecessary work for other people, and not being a bottleneck. Work ethic is about being a fundamentally good person that others can count on and enjoy working with.

So how do people get ahead if it’s not about outworking everyone else?

People make it because they’re talented, they’re lucky, they’re in the right place at the right time, they know how to work with other people, they know how to sell an idea, they know what moves people, they can tell a story, they know which details matter and which don’t, they can see the big and small pictures in every situation, and they know how to do something with an opportunity. And for so many other reasons.

So get the outwork myth out of your head. Stop equating work ethic with excessive work hours. Neither is going to get you ahead or help you find calm.

Work doesn’t happen at work

Ask people where they go when they really need to get something done. One answer you’ll rarely hear: the office.

That’s right. When you really need to get work done you rarely go into the office. Or, if you must, it’s early in the morning, late at night, or on the weekends. All the times when no one else is around. At that point it’s not even “the office”—it’s just a quiet space where you won’t be bothered.

Way too many people simply can’t get work done at work anymore.

It doesn’t make any sense. Companies pour gobs of money into buying or renting an office and filling it with desks, chairs, and computers. Then they arrange it all so that nobody can actually get anything done there.

Modern-day offices have become interruption factories. Merely walking in the door makes you a target for anyone else’s conversation, question, or irritation. When you’re on the inside, you’re a resource who can be polled, interrogated, or pulled into a meeting. And another meeting about that other meeting. How can you expect anyone to get work done in an environment like that?

It’s become fashionable to blame distractions at work on things like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. But these things aren’t the problem, any more than old-fashioned smoke breaks were the problem 30 years ago. Were cigarettes the problem with work back then?

The major distractions at work aren’t from the outside, they’re from the inside. The wandering manager constantly asking people how things are going, the meeting that accomplishes little but morphs into another meeting next week, the cramped quarters into which people are crammed like sardines, the ringing phones of the sales department, or the loud lunchroom down the hall from your desk. These are the toxic by-products of offices these days.

Ever notice how much work you get done on a plane or a train? Or, however perversely, on vacation? Or when you hide in the basement? Or on a late Sunday afternoon when you have nothing else to do but crack open the laptop and pound some keys? It’s in these moments—the moments far away from work, way outside the office—when it is the easiest to get work done. Interruption-free zones.

People aren’t working longer and later because there’s more work to do all of a sudden. People are working longer and later because they can’t get work done at work anymore!

Office hours

We have all sorts of experts at Basecamp. People who can answer questions about statistics, JavaScript event handling, database tipping points, network diagnostics, and tricky copyediting. If you work here and you need an answer, all you have to do is ping the expert.

That’s wonderful. And terrible.

It’s wonderful when the right answer unlocks insight or progress. But it’s terrible when that one expert is fielding their fifth random question of the day and suddenly the day is done.

The person with the question needed something and they got it. The person with the answer was doing something else and had to stop. That’s rarely a fair trade.

The problem comes when you make it too easy—and always acceptable—to pose any question as soon as it comes to mind. Most questions just aren’t that pressing, but the urge to ask the expert immediately is irresistible.

Now, if the sole reason they work there is to answer questions and be available for everyone else all day long, well, then, okay, sounds good. But our experts have their own work to do, too. You can’t have both.

Imagine the day of an expert who frequently gets interrupted by everyone else’s questions. They may be fielding none, a handful, or a dozen questions in a single day, who knows. What’s worse, they don’t know when these questions might come up. You can’t plan your own day if everyone else is using it up randomly.

So we borrowed an idea from academia: office hours. All subject-matter experts at Basecamp now publish office hours. For some that means an open afternoon every Tuesday. For others it might be one hour a day. It’s up to each expert to decide their availability.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: