По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

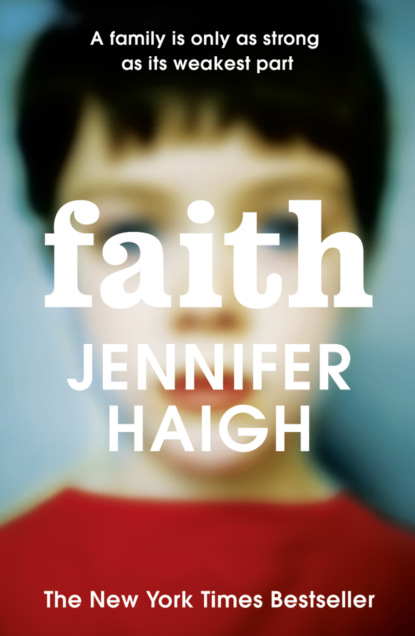

Faith

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Adult indifference, its power to motivate children, is old news in Catholic circles. My own mother practiced a version of this approach—by natural inclination, I suspect, more than by design. Father Fleury’s disregard was, to Art, oddly reassuring. He was unused to flatterers like Father Dowd, confused by male attention of any kind. With his stepfather, indifference was the best you could hope for. If you did anything to attract his notice, there would be hell to pay. But unlike Ted McGann, Father Fleury wasn’t volatile or angry, just preoccupied with other matters. Art lived to impress him. Years later he would recall the time he scored a 99 on a quarterly exam and was rewarded with a rare smile.

He had made no errors, but Father Fleury did not award 100s. He subtracted one point, always, for original sin.

Art had never had a father. When Ma’s first marriage was annulled—literally made into nothing—Harry Breen was expunged from the record. Art was the awkward reminder of a union that had, officially, never been. Now, suddenly, he had more fathers than he knew what to do with: Father Fleury, Father Koval, Father Frontino, Father Dowd. They taught him more than Latin and history, algebra and music. By word and example they taught priestliness: ways of speaking and acting; of not speaking and not acting. Restraint and discipline, obedience and silence.

For a shy boy, these formulas were a help and a comfort. Art didn’t miss his old school, the rough-and-tumble Grantham Junior High. St. John’s was a haven from all that frightened him, the alarming interplay of male and female, that intricate and wild dance. Like many boys he feared the opposite sex. But even more intensely, he feared his own.

A certain kind of boy unnerved him, hale athletes, confident and aggressive. At seminary such specimens were blessedly few. From the first it was clear that a range existed: alpha males at the one end; at the other, the distinctly effete. Both extremes were, to Art, alarming. Like Latin nouns, the boys came in three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. He placed himself in the third category, undifferentiated. In the seminary at least, it seemed the safest place to be.

Matters of sex, of maleness and femaleness, were in this world peripheral. He felt protected by silence, grateful at all that was left unsaid. Once, at a Lenten retreat, Father Koval had delivered a steely sermon, exhorting the boys to keep their vessels clean. To Art, at fifteen, the words remained mysteriously figurative, vaguely connected to all that had distressed him in his old life: at home, the nighttime noises from Ma and Ted’s bedroom; at school, the fragrant and fleshy presence of girls.

The life of a celibate priest. Father Koval had compared it to climbing Mount Everest: the outer limits of man’s capacity, a daring test that few were brave enough to attempt. The rhetoric was aimed at the boys’ nascent machismo; to Art, who had none, it rang false. A better comparison, he felt, was a journey on a spaceship. A priest was isolated and weightless. He existed outside gravity—the force that attracted bodies to other bodies, that tethered them to God’s earth.

ART GREW up in this atmosphere, outside gravity. Troubling questions were answered for him, and he accepted these answers in gratitude and relief. So when he graduated from high school and entered the seminary proper, he was unprepared for the sudden change in the weather. That September a new rector was brought over from Rome, a strapping, ursine priest named James Duke.

The previous rector had been mild and scholarly, a soft-spoken man with a distracted air. But Il Duce was another sort entirely. He exuded, by priestly standards, an air of raw masculinity; and surrounded himself with others—Father Noel Bearer, Father Stephen Hurley—of the same type.

The new regime seemed, at first, comically harmless. Their demeanor struck Art as clownish, a self-conscious parody of manliness. Then came the warnings—repeated with ominous frequency—against particular friendships. This injunction was not new. Close friendships violated the spirit of community; they were contrary to the Rule. Under the old rector, particular friendships had seldom been mentioned; now, suddenly, they seemed a matter of great concern. No suggestion was made, ever, of illicit affections between the men; but everyone was aware of the subtext. Art found himself avoiding his best friend Larry Person, who shared his interest in music. They no longer rode the T into Boston to hear Sunday concerts downtown. Smoking in the courtyard between classes, Art took notice of who else was standing at the ashtray. Groups of three or four were acceptable. Twosomes were inherently suspect.

Among the men paranoia blossomed—fears inflamed at the end of the school year, when a few were told by their confessors that the faculty harbored concerns. Art’s old cellmate Ray Cousins was censured for his distinctive voice. The criticism was so vaguely worded that Ray didn’t understand, at first, why he was being scolded. True, he admitted to Art, he wasn’t much of a singer; still, many a parish priest had learned to fake his way through the Mass. But Ray’s deficiency was not musical. His voice was high-pitched, with a discernible lisp. Suddenly Art no longer felt safe in the epicene middle. In the era of Il Duce, nobody was safe.

And yet somehow he came through unscathed; his own masculinity, however stunted and friable, was never questioned. At the time, and for years afterward, this fact astonished him. That spring he was chosen, at Father Fleury’s recommendation, to spend his four years of theology study at the Gregorian University in Rome, a rare distinction. To Clement Fleury he owed his escape.

I was a little girl when Art left for the Greg, too young to understand much of his business there. I do recall impressing my fourth-grade class with the postcards he sent me: the Colosseum and Forum and Trevi Fountain; multiple views of St. Peter’s, each bearing a florid stamp. Poste Vaticane.

One of these cards is still in my possession, a nighttime shot of the basilica Santa Maria Maggiore, an exquisite jewel box of a church. It is a glittering repository of Catholic treasure—priceless sculptures by Bernini and Jacometti, every flat surface bedecked with frescoes and mosaics. The ceiling, legend has it, is gilded in Inca gold. In Art’s opinion—inherited from Father Fleury—Santa Maria is more beautiful than St. Peter’s. Judging from my postcards, I would have to agree.

MEANWHILE, BEYOND the seminary walls, the world was changing. Art had been baptized into one Church, confirmed into another. A bold new pope, the astonishing Roncalli, had proclaimed an aggiornamento; a new day had dawned. The liturgy went from Latin to English. The altars were literally turned around backward, and priests said Mass while facing the congregation. In choir lofts, organs were joined by acoustic guitars.

It seemed inevitable that the changes would continue. True, Roncalli’s successor, Cardinal Montini, was no reformer; but Montini was not young. The next pope, it was said, would bring the Church into the twentieth (or at least the nineteenth) century, and perhaps beyond.

Art was twenty-five when he left Rome. He had traveled widely across Europe, seen every major cathedral in France and Spain. He returned to Boston with a powerful sense of mission, ready for ordination and all that lay beyond. Aggiornamento had inspired a whole generation. In Rome he’d met priests from Central and South America who spoke movingly of their people’s struggles, the Church’s power to effect social change. Activism was the Church’s future, and Art itched to be a part of it. For the diaconate year, as his classmates dispersed to local parishes, he was sent to a shelter for homeless men in the city’s South End. It was an unusual assignment, uniquely tailored to his tastes and aspirations. Once again, Father Fleury had worked his magic on Art’s behalf.

The South End has since gentrified, filled with posh restaurants and pricy boutiques, but in those days it still belonged to the poor. Each morning Art rode the T deep into Boston. At the shelter he ministered to the maimed and broken, the sick and delusional. There were men back from Vietnam, scarred by combat; lost inmates from state psychiatric hospitals decimated by budget cuts. There were addicts and runaways, boys barely out of childhood who came on buses to South Station and sold themselves on Washington Street. It was a veritable army of the needy, and yet the Archdiocese paid little attention. When Art arrived there, only one priest was seen in the shelters and on the streets. Art knew him by reputation only: the Street Priest, young and long-haired, who walked the Combat Zone in vests and blue jeans, seeking out the lost. The Street Priest’s apartment on Beacon Street was a gathering place for the desperate, the lonely and addicted. On Sunday mornings he said Mass there, with twenty or thirty runaways sitting Indian-style on the floor.

To Art it seemed the stuff of urban legend. He himself had handed out blankets and the Eucharist; occasionally he heard a garbled confession; but certainly he was no Street Priest. In his first week he was mugged at knifepoint. At the shelter he was treated as a curiosity, when he was noticed at all. If the Street Priest was the clergy’s future, Arthur Breen felt better qualified for the past.

In other ways, too, the future frightened him. The celibate priesthood—would it go the way of indulgences and Latin?—was a point of fierce controversy. He’d been a boy at St. John’s when he first heard this debate. At the time it caused him considerable distress. The priesthood had seemed to him ancient and unchanging. That it might, in a few years, transubstantiate, he found deeply unsettling. He’d been prepared and willing, at the rash age of fourteen, to give himself over to it entirely, in exchange for certain protections. He’d marked it definitively as his safe passage through the world, the only life, perhaps, to which he was suited. It seemed impossible that his Church would betray him in this way, change so profoundly the rules of the game.

He needn’t have worried. The changes never materialized. Amid much fanfare, the new Polish pope visited Boston. He flew directly from Ireland; at Holy Cross Cathedral he blessed the city’s two thousand priests. Later he said an outdoor Mass on the Common. A hundred thousand Catholics prayed in the rain. But in the ensuing years he would move the Church backward, not forward. To Art—a grown man then, and no longer so fearful—this was less reassuring than expected. For the Church, and for him, it seemed a missed opportunity. He wondered for the first time if they’d both made a mistake.

AFTER ORDINATION he was assigned to a parish, Holy Redeemer in suburban West Roxbury. He became a priest—a good one, he felt, though where was the proof ? His effect on the world, on the souls in his care, was frustratingly intangible. He felt keenly his own inadequacies. At first this awareness was constant, and nearly paralyzing. In later years it visited him periodically, a recognition of all he wasn’t and would never be.

He felt it most acutely in the confessional, that chamber of secrets. He was twenty-seven years old, but in most ways that mattered he felt like a child. Ted McGann, at his age, had spent six years in the Navy, had fathered two children. He had married Art’s mother at an age that seemed supernatural, and undoubtedly had women—perhaps many women—in the years before.

Art had known, always, that he was not like his stepfather. In the confessional he learned he wasn’t like other men, either. Men his age had wives and families; addictions, criminal records, mistresses, debts. They lived double and even triple lives, a fact that astonished him. To Father Breen, even a single life seemed a towering accomplishment.

He lived like a teenager in the parish rectory. It was an imposing place, three rambling stories. On the second floor lived a full-time director of music and the two young curates; Holy Redeemer was a large parish, wealthy enough to support a full staff. They lived in a warren of small bedrooms and shared a single bath. Upstairs was a plush suite of adjoining rooms, strictly off-limits. It was the exclusive domain of the pastor, Father Frank Lynch.

In every way Father Lynch lived above them. The whole house rang with his presence: his decisive step on the parquet floors, his manly laugh, his Old Spice cologne. To Art it was like suffering a second stepfather, only worse. Ted McGann’s style had been gruff indifference, but Father Lynch took palpable glee in tormenting him. Father Lynch was Ted times ten. At the dinner table he kept up a steady stream of banter, at the expense of Art or the other young curate—a Filipino named Renaldo Calderon, who spoke halting English and had the advantage of not understanding the pastor’s barbs. This left Art largely alone in his resentment of Father Lynch and his cronies, Father Bob DeSalvo and Father Marty Raab, local pastors who dined several times a week at Holy Redeemer. The three old boys had known each other for years; they’d developed a crude, jocular rapport more suited to a fraternity house than a rectory.

And yet a fraternity boy would enjoy far greater freedom than the young priests did. Ten o’clock was their unofficial curfew; at that hour Father Lynch locked the rectory door, and no one else was allowed a key. Mealtimes were sacrosanct, snacking forbidden. Art earned at that time a hundred dollars a week; he was saving up for a used car. On Monday mornings he took Communion to the local hospitals, driving the parish sedan. Every Sunday night he had to beg Father Lynch for the keys.

It was the old parish system—anachronistic in the late 1970s, a strange throwback. To Art, who still believed he was joining a progressive Church, the clerical pecking order came as a shock. But the Archdioceses of New York, Philadelphia and Boston—the hoary Irish axis—were notoriously conservative, still ruled by the old boys. For Frank Lynch and his ilk there had been no Roncalli, no aggiornamento. The Vatican Council had simply never taken place.

At the dinner table they lamented the liturgical changes: the jazzy new hymns, the hippy-dippy vestments; the ritual exchange of the Sign of Peace, in which the faithful shared greetings and handshakes and sometimes, to Frank Lynch’s disgust, kisses and hugs. “It’s one big communal love-in,” he groused. Bob and Marty chimed in with their own complaints: the infants bawling through the Consecration, the communicants who, imagining themselves invisible, sneaked out the side door after receiving the Sacrament instead of returning to their pews. Not to be outdone, Frank spun a yarn about the teenagers he’d caught playing cards in the choir loft, oblivious to the Mass taking place down below. To Art it was like being trapped at the table with three aging comedians, each trying to upstage the others. It seemed an occupational hazard: priests were used to having an audience, unaccustomed to sharing the floor.

At the table he was like a well-behaved child, seen and not heard. Yet in the parish his responsibilities were ponderously adult. Every Saturday, before evening Mass, he heard confessions. For two hours his parishioners confided their faults and failings; their most intimate affairs awaited his review. That he was expected to furnish guidance seemed utterly laughable—Arthur Breen, who’d known no intimacy of any kind. Yet no one else saw it; the cassock hid all that was lacking in him. It was to the cassock that these good souls confessed. Art imagined sending it to the confessional with no priest inside it, a long black robe dangling on a hanger. In many cases, it would have just as much wisdom to impart.

He felt, most of the time, like an impostor. Over the years he’d had fleeting doubts about his vocation. Always he had pushed them aside. Certainty will come later, Father Cronin had promised; but certainty had not come. Would the Lord have called a man so clearly lacking? He could have chosen anybody. Why would He settle for Arthur Breen?

Of course, he wasn’t entirely useless. Children adored him, lingering in his confessional. And the elderly asked little of him. Their expectations of the sacrament were largely ceremonial: a series of responses, a penance, a blessing. The problem was everyone in the middle, men and women in the jump of life, driven by human longings; crawling over each other like puppies in a dogpile, as Frank Lynch once said.

Art had spent his whole life in the company of men, and yet he found them hardest to counsel. Hard, even, to talk with. With priests he could hold his own in conversation, but laymen were a different matter entirely. In their company he felt irrelevant, tolerated out of politeness like a spinster aunt. The men of Holy Redeemer were OFD—Originally From Dorchester: hardworking guys who’d made it out to this middle-class suburb, but still rough at the core. On the church steps after Mass he saw them talking. What, exactly, did they talk about? In the spirit of preparation he studied the sports page, until Father Lynch caught him at it. “There will be a test later, Arthur,” he admonished in a simpering tone. The breakfast table erupted in laughter, and Art, mortified, abandoned his efforts. Who was he trying to fool?

With the parish women he had more success. About their concerns he understood even less, but their company was at least not adversarial. They mothered him. A cough or sniffle at the pulpit prompted a dozen worried inquiries. He was given hand-knitted scarves and sweaters, herbal teas and vitamins and once, an electric space heater. It must get drafty in the rectory, said the donor, one Mrs. Duddy, and in this she was not mistaken. The heater got him through a long Boston winter, until Frank Lynch discovered and confiscated it, grousing about the electric bills.

If all this feminine fussing was occasionally grating, Art never resisted. The parish women cared for him, and he was grateful for their affection. As human connection went, he was a beggar at the banquet, unable to refuse love of any kind.

Week after week they flocked to his confessional—Breen’s hen party, Frank Lynch called it, a sneer in his voice. Younger hens might have won his grudging respect, but these were past the age, women so long married that their husbands rarely figured in their confessions. They spoke of squabbles with other women, harsh words exchanged with sisters and daughters. It seemed that women, in the end, were concerned mainly with each other. Husbands became mere accessories, barely noticed, like the gold wedding bands they wore on swollen fingers and couldn’t take off if they’d tried.

It was a role that fit him comfortably: confessor to the matronly, the homely, the stout, the plain. Younger women confessed, too, though not as often; and with them Art was less easy. The prettier the woman, the more awkward he felt. This generation—his own generation—had a different understanding of the sacrament, whose name had been changed from Penance to Reconciliation. Some took the new name to heart, and pulled aside the grille for a face-to-face chat.

(Unless, of course, the revelations were of an intimate nature. Then the grille stayed closed.)

One such confessant he recalled distinctly. Cindy Clay was a Vietnam widow—Art’s age, slender and fair-haired. Her flowery perfume lingered in his confessional. For the rest of the afternoon he’d know she’d been there.

One Advent she made a memorable confession: she had used birth control. For no good reason Art felt himself sweating. As confessions went it was hardly incendiary: he had his own private doubts about Humanae Vitae, as did many priests he knew. The problem here was more basic: Cindy Clay had admitted contracepting, but not the act that necessitated it. In the eyes of the Church she was an unmarried woman, and the act in question was fornication. The facts of the matter were clear.

Had she been less attractive, he might have been able to say it. Instead he found himself dumbstruck. Hastily he assigned her a penance, falling back with relief on the familiar words. Go in peace and sin no more. He pronounced the last words with particular emphasis, as though they exonerated him. As though in speaking them, he had discharged his duty.

On the other side of the screen the kneeler creaked. Cindy Clay rose to go, a cloud of lilacs in her wake.

EVERY PARISH had a Cindy Clay, or several. He was assigned next to St. Rose of Lima, on the North Shore. It was a parish of young families, its elementary school thriving. As the new assistant pastor, Father Breen functioned as a kind of youth minister, a duty that suited him perfectly. He trained altar boys and spoke to Confirmation classes. He did sacrament preparation for the tiny First Communicants, and subbed for a religion teacher in the parish school. The young mothers were his own age, grateful for his involvement. More than once he heard the wistful compliment—You would have been a wonderful father, Father—in a tone that was nearly flirtatious. If there was a proper way, a priestly way, of responding, Art never found it. He blushed, stammered, mumbled. Thank you. You’re very kind.

Holy Redeemer, St. Rose, Our Mother of Sorrows: Art’s life as a priest divided into chapters. The newspaper accounts mention them only briefly. Father Breen served without incident.

In the spring of 1994 he was assigned to Sacred Heart.

Part 1

2002

Chapter 4

Holy Week, for a priest, is like the year’s first snowfall: he knows it’s coming, yet somehow it always catches him off guard. The crowded Masses, the hundreds of confessions, the sickbed visits; the extra hours of sermon preparation, in a vain attempt to avoid repeating what’s been said a thousand times before. The hectic pace is shocking to a man who feels marginally useful most of the time. Art understood that to most of his flock, his services were not essential. At their baptisms, marriages and funerals his presence was expected, but in the intervening years they scarcely gave him a thought.

He had grown up in the priesthood, and grown tired. In his early fifties he’d begun to grow old. He was a slight, nervous man, prone to stomach upset and a yearly bout of bronchitis—ailments he blamed on his two vices, coffee and cigarettes, dissipations even a priest was allowed. Over the years he’d lost hair and weight, energy and stamina. He felt, increasingly, that he’d lost his way. That Lenten season—the season of repentance—had shaken him profoundly. This year he had a great deal to repent. And yet, as he prepared to celebrate the Resurrection and Ascension, he felt a glimmer of his old sense of purpose, like a dream remembered. The sensation was short-lived but potent. It seemed, however briefly, that aggiornamento was still possible. That a new life lay ahead.