По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

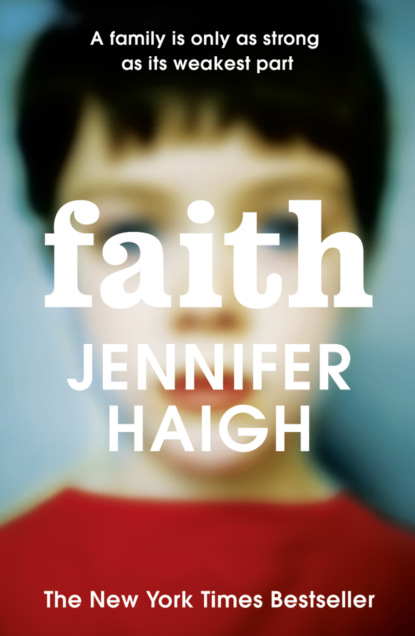

Faith

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

North Fenno was short and narrow, the houses set close to the curb. Aidan and Kath lived on the first floor, in a shotgun apartment with a kitchen at the rear. Art drove past slowly, noting lights in the windows, Aidan’s yellow toboggan still lying on the front porch, though the snow had melted a month ago.

Kevin Vick’s beat-up red Camaro was parked at the curb.

Well, now what? Art thought. At one time he would have knocked at the door, but those days were gone forever.

(And if he had gone to her door that night—would this have changed anything? It seems unlikely. The match had been struck, the fuse already lit.)

In the end he turned the car around and headed for the rectory. He would do as Fran had asked: he would remember Kath and Aidan in his prayers.

BACK AT the rectory, beside the old rotary phone, he found a stack of messages. It was the usual mix of parish business. Sister Ursula, the school principal, had set a rehearsal date for the eighth-grade commencement. A young bride had called to schedule her wedding. (In all his years as a parish priest, Art had never received a phone call from a groom.) Only two of the messages could be called personal: one from his old friend Clem Fleury in Rome, another from Sheila, me, in Philadelphia. They were recorded faithfully in Fran’s neat handwriting, indistinguishable from my own or my mother’s or my aunt Clare’s—evidence of our shared education, twelve years in the parochial schools. (My brother Mike, taught by the same nuns, writes illegible chicken scratch, as do my father and his brother and all their male children. I think back to those school papers corrected in red ink—Penmanship!—marked down half a grade if an i was left undotted, a t uncrossed. Maybe only the girls were penalized in this way.)

Messages in hand, Art retreated upstairs. With Father Aloysius gone, he had the run of the place; but from long habit—he had lived his whole life in shared housing—he avoided the common areas, the dark parlor and stiff sitting room. I would see these rooms a week later, when I came to help Art pack his few possessions before the Archdiocese changed the locks. Undoubtedly the circumstances influenced my perception; still, I pitied the engaged couples reporting for their mandatory Pre-Cana counseling, squirming for hours in those punishingly uncomfortable chairs. Art felt at ease only in the cluttered front room, which served as the parish office, and in Fran Conlon’s kitchen, with its lingering smell of breakfast. He spent the rest of his time in his bedroom, which he’d outfitted with a stereo and portable TV. Also a cordless telephone, from which he returned my call.

He left a message I now know by heart. I have replayed it several times, analyzing the tone of his voice. Sheila, it’s me, Brother Father. The man in black. I’ve escaped from a hostage situation, three hours with the parish council. I’m slammed tomorrow, so I’ll try you on Friday. If he had any inkling of what was about to happen, he gave no indication. There was no hint of distress in his voice.

I HAVE reconstructed his movements the next day, Holy Thursday. I have in my possession Art’s desk planner, its black leather cover embossed with the numerals 2002. From long practice I decipher his cramped handwriting (he too, it seems, was given a pass on penmanship). At 9 A.M. he attended a fellowship breakfast at St. Thomas Presbyterian, sponsored by the local Ecumenical Council. In the afternoon he heard confessions and gave the sacrament at Mountain View nursing home. On the same page, I found a yellow Post-it note: Drop by choir rehearsal. He had doubts about the new director and feared a disaster on Sunday morning, her first Easter at Sacred Heart. Thursday evening he celebrated the annual Mass of the Lord’s Supper, a ninety-minute extravaganza complete with full choir, trumpets from the eighth-grade orchestra and the ritual foot-washing, Art kneeling at the altar before twelve barefoot parishioners, like Christ bathing the feet of the Apostles. Afterward the Eucharist would be carried, in solemn procession, to the Repository. With luck he’d eat supper by midnight. Fran would be long gone, and he’d have no chance to question her about Kevin Vick. He would sit in the kitchen with the Atlantic Monthly, eating whatever she’d left in the refrigerator, then rush through his prayers and fall exhausted into bed.

Which brings us to Friday morning, the Friday in question. Good Friday, if you are raised Catholic, is something of a trial—an endless day to be loathed and dreaded, if you are the Catholic child of Mary McGann. Each year Mike and I suffered it together: a day of no school, no television, no loud playing; a day of rosaries and soggy fried fish. My mother took a certain pleasure in disparaging our flimsy modern devotions—put to shame, she claimed, by the extreme rites of her girlhood, Good Friday as it was meant to be observed, at her childhood parish in Roxbury. From noon to 3 P.M., the hours Our Lord spent hanging on the cross, young Mary Devine had knelt in prayer, with nothing but a piece of toast in her stomach. (Having strictly observed the Friday fast, one full meal per day, and that without meat.)

Off to church now, she’d conclude sourly. What’s left of it. At this Mike would stare at me with mournful pious eyes and we would both fall out laughing, and Ma would bemoan the fate of our souls.

Though it was rough going for the faithful, a priest’s Good Friday duties were light. Mass could not be celebrated, which was itself a rare freedom. Years ago, when Art was a lowly cleric at Holy Redeemer, Frank Lynch had declared Holy Thursday an all-night poker game. Priests from the surrounding parishes drank until dawn and slept until noon, the one day of the year they were excused from morning Mass.

In Art’s datebook, that morning is blank. At 2 P.M. he would lead the Solemn Commemoration of the Lord’s Passion. In the evening he was expected at the newly concocted Family Service, led by parishioners, and the elementary school’s performance of the Passion Play.

As it turned out, he did none of these things. His calendar makes no mention of what actually happened, the 10 A.M. phone call from Bishop John Gilman, an aide to the Cardinal.

At ten-fifteen Art got in his car and drove to Lake Street.

Chapter 5

It takes nearly an hour to drive from Grantham to Brighton, where the Boston Archdiocese was then headquartered. Art traveled west on Commonwealth Avenue, the road climbing and dipping through the suburbs of Brookline and Allston. What was he thinking as he drove? He told me later that he’d had no idea why he’d been summoned, which seems incredible. For months the entire city had been reading about the scandal, priests from all over the Archdiocese accused, reprimanded, exposed.

“Okay, I had an idea,” he admitted when I pressed him. “But my idea was completely wrong.”

To make sense of this, I’ve had to think about what it was like to be a priest in Boston that spring, when anyone in a collar was suspect. “Maybe we were paranoid,” Father Fleury told me later, “but it seemed that the whole world suddenly looked at us sideways.” One after another reputations were destroyed, careers ended, lives ruined. Among the first to fall was the Street Priest who’d walked the Combat Zone: at his apartment on Beacon Street, he’d apparently offered more than a weekly Mass. Amazingly, no one suspected it at the time. No one gave a thought to those lost children sitting cross-legged on his floor, the Street Priest looking down on them from a great height as they received the Eucharist from his hands.

To Art, one allegation was even more shocking. Ray Cousins, his old cellmate, had been accused of molesting a boy. Ray was a gentle soul—“the last guy you’d ever suspect”—but the Archdiocese was making an example of him. The Cardinal had been widely vilified for covering up such allegations, so now he made a great show—just for appearances, Art insisted, pro forma tantum—of taking every accusation seriously. Anyone who’d ever known Ray was being interrogated. Naturally Art’s name would be on the list.

So as my brother drove the final hill into Brighton, it was Ray Cousins he considered: could it possibly be true?

At the bottom of the hill he slammed on the brakes. Comm Ave. was clogged with traffic, vans and trucks parked on both sides of the road, some with engines idling, satellite dishes attached to their roofs. Well, of course: nearly every night the local news featured a dispatch from Lake Street, the Cardinal’s response—or usually, his silence—at each new allegation of abuse. For these segments the Chancery was always the backdrop, a reporter standing before the building as though at any minute His Eminence might emerge.

Art drove past the news vans and took the long way around, through the back entrance. He parked behind the Chancery, where Church business was conducted. After the death of the great O’Connell, his successor—my mother’s hero, Cardinal Cushing—had made this addition to the campus. The Chancery is a square brick bunker, of a utilitarian ugliness so incongruous that it seems intentional, as though Cushing—a local boy, a famous populist—had been making a point.

As promised, Art’s official escort was waiting at the rear door. Gary Moriconi stood with his back to the building—coatless, smoking, his cassock flapping in the wind. “Of all people,” Art fumed to me later. I have since met Father Gary, a short, stocky man with a barrel chest and a memorable voice, nasal and high-pitched, that doesn’t match his body. He was Art’s age, fifty-one, yet his dark hair was suspiciously free of gray.

The two greeted each other with a wariness that went back many years. At seminary they’d been classmates, but not friends. Art saw at a glance that Gary knew exactly why he’d been summoned, which was not surprising. He had always been privy to secrets.

“They’re waiting for you,” Gary said archly. He took a final drag and butted his cigarette—a large ash can had been placed at the door for this purpose. But instead of leading Art into the Chancery, he turned and started up the hill.

“I didn’t understand, at first, where we were going,” Art explained to me later. But as he followed Gary up the wet footpath, the grass soaking his wingtips, it dawned on him that he would be seeing the Cardinal at home—in the mansion referred to, with audible capitals, as The Residence.

He was alarmed then, but only for a moment—because as they climbed the hill, he saw that the change of venue had nothing to do with him. The Cardinal couldn’t take any meeting in the Chancery. On the sidewalk below, a crowd had gathered: men and women milling about, drinking coffee, talking on cell phones. His Eminence wanted to avoid the long unprotected walk across the lawn, in full view of the TV cameras. “The perp walk,” Art told me later, with a wincing smile.

Vigor in Arduis.

“Vultures,” said Gary. “They’re here every day.”

They entered The Residence through a porte cochere and headed down a long passageway, their wet shoes squeaking on the marble floors.

“I’ve never been inside before,” Art admitted.

“Never?” Gary sounded incredulous. “It’s a pity you couldn’t see it in nicer weather. In summer the gardens are spectacular.”

“So I’ve heard.” Art knew—everyone did—about the Cardinal’s annual Garden Party, where his favorite priests mingled with politicians and millionaires, the benefactors of Catholic Boston. Of course Gary Moriconi would be invited. It was just the sort of gathering he’d enjoy.

“Down the hall is the chapel, where they film the TV Mass on Sundays. Upstairs are meeting rooms and the Cardinal’s quarters.” Gary seemed to enjoy playing tour guide. Certainly he knew his subject. He’d spent twenty-five years, his entire career, crisscrossing these grassy lawns. After ordination he’d stayed on at St. John’s, in an administrative post created especially for him. He’d remained an amanuensis to the powerful, an eager mouthpiece.

“Have a seat.” Upholstered settees had been placed here and there against the walls. “I’ll let them know you’re here.”

He continued down the corridor and knocked lightly at a closed door. Alone, Art paced the long hallway. On both walls, hung at ten-foot intervals, were portraits of the current Cardinal. Some were skillful; others might have been made by children. One in particular caught Art’s eye: His Eminence as a young priest, rendered in oils. It reminded him of an old colorized photograph, the young man with a high flush in his cheeks, as though they’d been smeared with rouge.

A moment later Gary reappeared. “This way.” He led Art into a large anteroom with more couches, backed against the walls as if to clear the floor for dancing. The thin gray carpeting could have used a cleaning. The walls were bare. The Residence, impressive as it was, lacked a single piece of art that did not depict the Cardinal. There was not even a nice reproduction of a Giotto. Art sat, watching a set of double doors.

In a moment the doors opened. “Arthur.” Bishop John Gilman, the Vicar General, crossed the floor briskly, a small, spry man in a black suit. He gave Art’s hand a cursory shake. The gold pectoral cross was hidden in his jacket pocket. Only its chain was visible, looped across his black rabat.

“Come in, come in. His Eminence has another appointment at noon.”

Art followed him into an inner office, a high, shadowy room crowded with furniture. The Cardinal sat at a hulking wooden desk, his back to a window. His face was familiar as a relative’s: the shock of silver hair, the meaty jowls. His hooded eyes were furtive and intelligent, his heavy brows like eaves covered with snow.

He rose—a big man, hunched and imposing in his black cassock—and took Art’s hand in both of his. It was a trademark of sorts, like the cassock’s red piping and matching buttons: the Cardinal’s famous two-handed shake.

“Arthur, thank you for coming,” he said, as though they were old friends. As though, in the Cardinal’s eighteen years in Boston, they had ever exchanged a word.

Art followed him to a round table at the other end of the room. The Cardinal sat heavily. On the table was a single sheet of paper. He laid his hand upon it, as if to show off his massive gold ring.

“This arrived in yesterday’s mail.”

From across the table Art peered at the document, a letter on law firm stationery. The text was brief, nearly covered by the Cardinal’s hand.

The whole ordeal lasted fifteen minutes. After the initial revelation Bishop Gilman took over. His cheeks, Art noticed, were flushed; a patch of psoriasis bloomed beneath one ear. This made him look agitated, in the throes of some high anguish, yet his tone was matter-of-fact. Calmly he explained the particulars: Art would be placed on leave but would continue to receive his salary; would be covered, as always, by the Archdiocese’s health insurance. He was to vacate Church premises immediately, Gilman said with emphasis. That was the most important thing.

“Where do I go?” Art asked.

The bishop took a business card from his chest pocket. On the back of it he wrote an address. “We took the liberty of renting you an apartment. Temporarily, of course. Until we get this straightened out.”

In the end they told him nothing: not the name of the accuser; not even what he was supposed to have done. Art had asked both questions immediately; both times Gilman looked expectantly at the Cardinal, who silently bowed his head.