По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

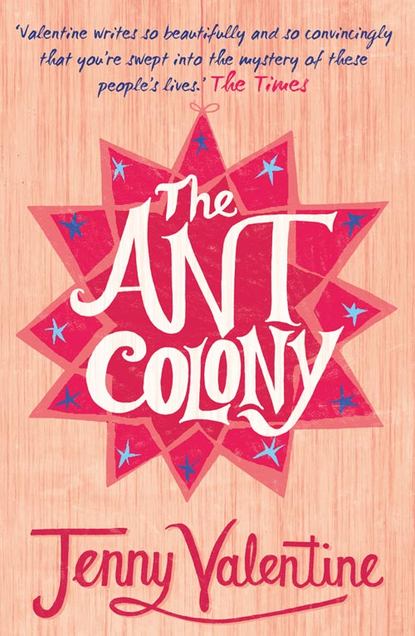

The Ant Colony

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The place had a little kitchen and a bigger room for everything else, like eating and reading and sitting and thinking and sleeping. The floorboards were painted in thick black gloss with stuff trapped in it, hairs and fluff and sharper lumps, like bugs in amber. There were two massive windows, floor to ceiling, that flooded the place with streetlight all night long and let in the sounds of outside. You are never alone with noise and light, not completely.

From my windows I could see straight into other windows, then across the pattern of rooftops and into the tower of a Greek Orthodox church, and down on to the street below. I spent a long time looking.

It took me about a week to remember where I was when I woke up.

On the first day I cleaned the flat. I found a folded-up note between the floorboards that said please let me stay in this house forever, please let me, please. The handwriting was small and spiky and distinctive, all the words joined together like one long word. I closed it up and put it back where I found it, and I felt sorry that whoever wrote it didn’t get what they wanted. I felt sorry for them that I was there instead.

When everything was clean I unpacked my bag, which took all of ten seconds. Two T-shirts, three pairs of socks, a spare pair of jeans, toothbrush, toothpaste and soap, a spare jumper, the school uniform I’d taken off, the shell of my phone and two unreadable books which belonged to Max and should have been given back a long time ago.

On the second day I hung blankets on the windows, but they kept falling down so I gave up and learned how to live in a goldfish bowl without caring, like everyone else.

On the third I worked out how to use the little oven. Someone else’s cooking burned off the red elements and filled the room with hot, damp smoke.

On the fourth someone upstairs had a domestic in the darker hours of morning. Things kept falling past my windows on to the road below. Clothes float with grace and land silently, while cutlery is more chaotic.

On the fifth the electricity kicked out halfway through my shower because I’d forgotten to charge my top-up key.

On the sixth I walked in on somebody in the communal bathroom. They were just a shadow behind a curtain, but they were shouting.

On the seventh I ate toast and cream of tomato soup for the fourth time that week, and I thought about home and how I could never go back there.

On the eighth day it was raining. I watched the puddles growing on the road. Why did it make me think about me and Max, staying late at school? I didn’t want it to. It was the rain and the books by my bed that did it.

Max was chess club and I was football. I can’t play chess and he’s rubbish at football. Mum drove him home across the wind battered common which was bedraggled with sheep and rotting bracken. The house stood at a bend in the road, an L-shaped farmhouse with geese and dogs and mud in the yard. It had rained and the road was streaming down the hill towards us, and the windscreen was blind with puddle water.

We walked through his yard to the front door while Mum turned the car around. He didn’t knock. We just walked in and left our shoes inside the door. The house was warm and smelt of cinnamon, gold and orange against the grey of outside. I followed him into the kitchen and his mum was there, warming herself like a cat against the Aga.

Max’s mum didn’t think much of me. “Hello,” she said, and Max pretty much ignored her, but I looked at her and smiled because she wasn’t my family to ignore. Her hair was wet, bleeding water into the fabric of her shirt like blotting paper.

Max grabbed two apples from the fruit bowl and offered one to me across the table. I shook my head, so he offered it to her and she took it and bit hard. It was quiet between the three of us, and awkward.

“Wait there,” Max said suddenly without looking at me. “I’ll just get that thing.”

I had no idea what he was talking about.

I stayed where I was while he climbed the stairs and walked across the room over our heads. I listened to the wall clock and the hum of the fridge. There was a hole in my sock.

Max’s mum didn’t talk to me. She finished the apple. She arched her back and stretched her arms above her head. I saw the skin at her hips, above her jeans, below the lift of her shirt. Then she turned her back and filled a saucepan at the sink, started chopping carrots. I wasn’t there to her. I might have been a ghost in the room.

I was glad when Max came back with the thing – a book he’d been talking about in the car, something complicated about life on other planets. According to this book, there were so many galaxies and universes out there, even if the odds against life were a billion to one, there’d still be a billion planets teeming with it. As he gave it to me his mum looked at us and laughed quickly to herself. She knew I was never going to read it. I could tell just by the cover that I’d get bogged down on the first page and never pick it up again.

But Max wanted me to leave with something, if not an apple then a book, so I took it. I held its spine and flicked through the pages with my thumb. Mum beeped outside in the yard and I said I should be going, and Max’s mum left the room.

“See you mate,” I said, and Max said, “Bye,” and she said nothing.

I was putting my shoes back on at the door when he came running out of the kitchen. His socks made a shushing noise on the floorboards.

“Take this one as well,” he said. He was out of breath.

“Another book,” I said.

“The Ant Colony,” he said, in a voice like you hear at the cinema. “By Dr Bernard O Hopkins.”

I laughed. “Thanks Max.”

“It’s brilliant,” he said, looking at the book and not at me. “A real page turner.”

It was so like Max to talk about an ant book like that, like it was a thriller or something.

I said, “I won’t be able to put it down.”

He nodded, like that was the right answer, and he stood in the orange light of the doorway and watched me walk to the car.

On the drive home Mum and I talked about the books Max had given me. “Ants?” she said. “What a surprise.” Because Max was obsessed with them, how organised they were, how many of them there might be, how they all worked together like one animal. Max told me a long time ago that looking down at them made him think he was a giant towering over the earth.

Ants were what we did when we were seven and eight and nine. It was all Max wanted to do. I was like the genius professor’s assistant or something. We dug and photographed and measured. We tracked and timed and watched. We collected them in bottles. Max pickled specimens in vinegar and kept them in the garden shed. He’d forget where we were and who I was even, and everything was just about the ants.

When we got older, and everyone wanted to play football and drive cars on the common and get wrecked and show off down the river to girls, Max was still into ants. There wasn’t a cure for his ant thing.

I showed Mum the other book. I said, “Do you think the life on other planets idea comes from watching ants?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, ants are kind of weird, like from outer space, and Max has told me before he thinks humans are just like ants, even less if you put them in the context of the universe,”

“Very scientific.” Mum was smiling at me. “Some of his brain cells are rubbing off.”

“Leave it out, Mum,” I said.

She said, “I get vertigo just thinking about life on this planet, never mind scouting around somewhere else for more.”

We started inventing intergalactic package holidays, imagining a time when everybody had got bored of space travel because it was too easy, because everyone was doing it, because it was just not cool. I said Max might find someone nearer his IQ on planet Zargon.

Mum said, “What planet is he going to find his people skills on?”

She said this because Max is one of those clever people who are also about the shyest, most awkward you could meet. Often this can be mistaken for just rude.

“He was talking to you,” I said to Mum. “That’s a start isn’t it?”

“When was he talking to me?” she said.

“Today, in the car, about the book.”

“No,” she said, “he was talking to you.”

I smiled at Mum. “He was talking to you. He was looking at me.”

“See?” she said. “People skills. How do you know that anyway?”