По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

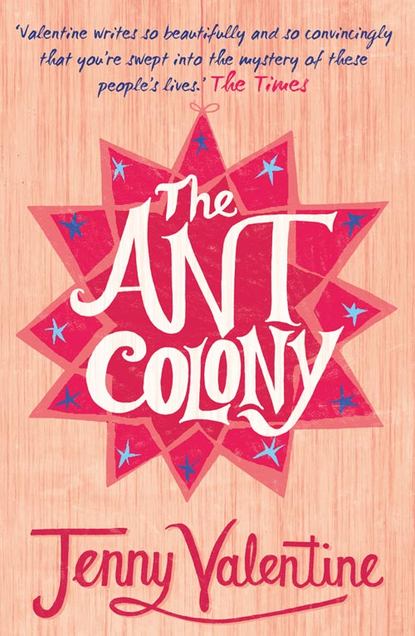

The Ant Colony

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I bet he did. You tell her I can always babysit if she needs.”

“I don’t need a babysitter. I can sit myself,” I said.

“Well, not when you’re ten dear, that’s not really allowed. But you know where I am.”

That’s when I told her the rules of babysitting because I found them out once in a library, to be sure. The rules are that you can leave your child at home whenever you like as long as you can get home in fifteen minutes and they are good at looking after themselves and being sensible and they have your phone number somewhere. So seeing as I’m very sensible and the pub was only down the road, I wouldn’t be needing a babysitter at all. That’s what I told her.

Nobody ever believes me. Isabel didn’t believe me either. She scribbled her phone number on a piece of paper and then she made me learn it and say it to her without looking, and then she asked me what I wanted on my toast.

“Anything.”

She asked me if I slept well and I said, “Fine, thanks. Me and Mum slept like logs.” I crossed my fingers she didn’t hear Mum coming in at four in the morning. I know it was four cos she made so much noise doing it. I think she tripped over and whoever was with her couldn’t see well enough in the dark to help her up. I think it was Steve.

I said, “Mum?” And I sat up in bed to see what was going on.

Mum said, “Shush, go to sleep, it’s four o’clock in the morning.” So that’s how I know.

They went into the kitchen and sat on the floor, and Steve must’ve been a very funny man cos Mum was just laughing and laughing. Maybe he told Mum about his facial peel.

I smiled at Isabel right through my lie, without even blinking, and she smiled back exactly the same, so maybe she knew and maybe she didn’t, but neither of us was going to say.

She put a pile of toast on the table. Isabel made her own bread. It had all lumps and bits in it, but it wasn’t as bad as it sounds.

I was on about my fifth bit when I heard Mum’s shoes on the stairs. She was coming down carefully cos of the heels. I could picture her, sort of sideways and a bit stiff looking, pressing her hands against the walls. I brushed the crumbs off my front and Doormat jumped up and started hoovering them straight away, like a living, breathing dust buster. He followed me when I went and put my head out the door. Maybe he thought I’d leave a trail of crumbs.

“What are you doing in there?” Mum said. She looked pretty and important, and you couldn’t tell she’d had two late nights in a row at all.

“Just visiting Isabel.”

“Oh yeah?” she said and she came in the flat and almost trod on the dog. “Oh shit!” she said “Sorry, dog,” as she walked in the kitchen.

“It’s funny cos his name is Doormat,” I said to her, but it was only me who was laughing.

“Hello, Isabel,” she said and she sounded really loud in the tiny kitchen. “I’m Cherry, Bo’s mum. Is she bothering you at all? You all right with her in here?”

“I invited her in,” Isabel said. She wasn’t really smiling.

“Well, that’s nice,” Mum said. “I’m off now. Job interview. I’ll be back in a bit. Wish me luck.”

I put my arms round her waist and she smelled all lovely, and she kissed me in that way she does when she’s thinking about her lipstick, all gentle and hardly there, like an eyelash or a butterfly.

Mum was almost out the door when Isabel called after her, asking should she give me my lunch as well as my breakfast. There was a bit of an edge in the way she said it that made me feel bad for eating so much toast.

“No need,” Mum said, clicking back in and looking hard at me. “I’ll be back by then. And Bo has lunch money, don’t you, darling?”

I shook my head. It was quiet and nobody moved. I counted to three. Then Mum opened her purse and shoved a crumpled fiver in my hand. It was soft and old like tissue. I opened it out to have a proper look. I didn’t know what to think. I never normally got that much just for lunch.

Mum told me not to spend it all at once and then she said, “Come and kiss me goodbye then.”

I followed her to the door. She took the fiver off me and put it back in her purse. “Sorry, Bo,” she said. “It’s all we’ve got. I won’t be long. I’ll bring you back a sandwich or something.”

And then she was gone.

I pretended to be putting the money in my pocket when I walked back in. I didn’t want Isabel thinking anything about anything.

Five (Sam) (#ulink_c9b21bba-cf5d-59ea-b384-20d9114c77a0)

The old lady on the ground floor was nocturnal and so was her dog, probably through habit rather than choice, because she walked it in the middle of the night. I know because that’s how we met, on my eighth day. She got locked out at half past four in the morning. I believed her at the time anyway. She was the first person to speak to me in my new life.

There was a park just round the corner. I learned to call it a park, but actually it was a patch of grass with two benches and some bushes and a bin for dog shit. It was also an openair crack house. Isabel told me, but she clearly didn’t care. She’d been there the night I had to let her in. She threw stones at my window. I thought I’d dreamed them.

“Oi!” she said in this shouting sort of whisper. “Country! Get down here and open the door.”

I had to put some clothes on. The stairs were cold and gritty under my feet and I could hardly see. I thought I might still be asleep. She stood there on the doorstep like I’d shown up three hours late to collect her.

“Doesn’t anyone brush their hair any more?” she said.

It felt strange, someone talking to me, like having a spotlight shined in my eyes.

“How long’ve you been here?” she said.

I had to clear my throat to speak, like it was rusty. “I just got up,” I said.

“No, Einstein, how long’ve you lived here?” she said.

“Oh. About ten days.”

“I haven’t seen you,” she said, like that meant I was lying. She was feeling about for her spare key above the doorframe but she wasn’t quite tall enough to reach.

“Well, I’ve been here,” I said. “I’ve been keeping to myself.” I got the key for her.

She looked me up and down and laughed once. “Pink lung disease.”

“What?”

“Pink lung disease. Don’t you young people know anything?”

She told me about this policeman at the dawn of the motor age who got sent from his village to do traffic duty in Piccadilly. He wasn’t any good at directing traffic. Nobody was because it was a new thing. The policeman got hit by a car and he died. The doctor who cut him up had never seen healthy, pink, country lungs before. He was used to city lungs, all black and gooey, so he said that was the cause of it. Pink lung disease. Not a car driving over him at all.

She looked at me the whole time she was talking. She was the very first person to see me since I’d been here. I was conscious of it.

“You’ve got lovely country skin,” she said. “Look at the glow on you.”

“Thanks,” I said, because I didn’t know how else to take it.

“You stick out like a sore thumb with that healthy skin.”

“No I don’t,” I said.