По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

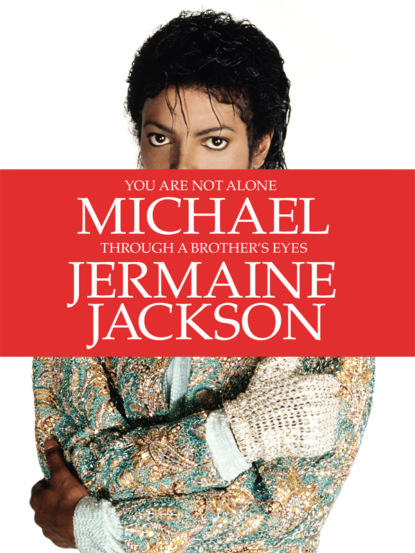

You Are Not Alone: Michael, Through a Brother’s Eyes

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Straightaway, Richard put together a professional pitch-package that contained our Steeltown hits, newspaper cuttings of rave reviews, promotional material and a letter explaining why the Jackson 5 should be given a chance. It was dispatched to labels such as Atlantic, CBS, Warner and Capitol. In addition, Joseph personally mailed a package to Motown Records in Detroit, addressed to Mr Berry Gordy, hoping to follow up on Gladys Knight’s recommendation. Apparently he used to tell Mother: ‘I’m going to take the boys to Motown if it’s the last thing I do!’

Many weeks later, and with us still technically attached to Steeltown Records, Joseph brought in an envelope, opened it and our demo tape slid out on to the table … Returned and rejected by Motown.

THE BEST THING ABOUT JOURNEYING THE Chitlin’ Circuit was the feeling that we were always tiptoeing in the shadows of the greats. We had already found ourselves in the dressing room of Gladys Knight and on the same stage as the Delfonics, the Coasters, the Four Tops and the Impressions but two thrilling ‘meets’ were golden and both at the Regal in Chicago.

On the first occasion, we were either waiting for Smokey Robinson to head to rehearsal or go onstage to perform. I can’t remember which. But Joseph reassured us that if we hung around and behaved ourselves, we’d get to meet the greatest songwriter of all time. That was one of the few times we’d ever feel butterflies in the stomach: getting ready to meet one of our heroes was more nerve-racking than performing.

When Smokey walked up to us and stopped to talk, we couldn’t believe he was actually taking time out for us. But there he stood, in a black turtleneck and pants, smiling broadly and shaking our hands, asking who we were and what we did. Michael was always intrigued by another artist’s way of doing things. He peppered Smokey with questions. How did you write all those songs? When do the songs come to you? I don’t remember the answers but I’ll guarantee that Michael did. Smokey gave us a good five minutes – and when he walked away, you know what we talked about? His hands. ‘Did you feel how soft his hands were?’ whispered Michael.

‘No wonder,’ I said. ‘He ain’t done nothing but write songs.’

‘They were softer than Mother’s!’ Michael added.

When we burst through the door in Gary, it was the first thing we told Mother, too. ‘MOTHER! We met Smokey Robinson – and you know how soft his hands were?’

That’s what people forget. We were fans long before we became anything else.

The day we met Jackie Wilson we advanced one stage further with our VIP access: we were invited into his hallowed dressing room. It was ‘hallowed’ because, to us, he was the black Elvis before the white Elvis had come along, one of those once-in-every-generation entertainers. Jackie and his revue were regular headliners at the Regal so our sole focus that day was to meet him. After Joseph had had a word with someone, we got the ‘Okay, five minutes’ privilege that our boyhood cuteness often bought. I’ll say this about our father: he knew how to open doors.

This big-name door opened and we entered single file from the darkness of the corridor into the brightness cast by the light-bulbs arcing around the dressing-table mirror, where Jackie was seated with his back to us. He had a towel wrapped into a thick collar to protect his white shirt from the foundation and eye-liner he was self-applying.

It was Michael who spoke up first, politely wondering if he could ask him some questions.

‘Sure, go ahead, kid,’ said Jackie, speaking to our reflections in his mirror.

He then bombarded him with questions. How does it feel when you go on stage? How much do you rehearse? How young were you when you started? My brother was relentless in his quest for knowledge.

But it was Joseph who handed us the biggest piece of information to take away that night: he told us that some of Jackie Wilson’s songs had been written by none other than Mr Gordy, the founder of Motown. (‘Lonely Teardrops’ had been Mr Gordy’s first No. 1.)

In meeting both Smokey Robinson and Jackie Wilson, we all knew theirs was the level where we needed to be. Maybe that was what Joseph had been doing all along: introducing us to the kings so that we, too, would want to rule. It was almost like he was saying, ‘This can be you – but you’ve got to keep working at it.’

I wish I could remember the pearls of show-business wisdom that each man left us with – because each one had ‘sound advice’, according to Joseph – but those words are now buried treasure somewhere deep in my mind. Michael hoarded these influences, absorbing every last detail: the way they talked, moved, spoke – and how their skin looked and felt. He watched them on stage with the scrutiny of a young director, focusing on Smokey’s words, focusing on Jackie’s feet. Then, in the van going home afterwards, he became the most vocal and animated out of all of us: ‘Did you hear when he said …’ or ‘Did you notice that …’ or ‘Did you see Jackie do that move …’ My brother was a master studier of people and never forgot a thing, filing it away in a mental folder he might well have called ‘Greatest Inspirations & Influences’.

WE WERE NOW EARNING ABOUT 500 dollars a show and our father worked us harder than ever, with an unremitting expectation of precision. ‘We’ve done this over and over. WHY are you forgetting what to do?’ he shouted, when a song or a move broke down – and then reminded us that James Brown used to fine his Famous Flames whenever they made a mistake.

But fines weren’t Joseph’s choice of sanction. Whippings were. Marlon got it the most because he was singled out as the weak link in the chain. It’s true that he wasn’t the most co-ordinated, and he had to work 10 times harder than the rest of us, but none of us saw anything in him that hampered our performance. But Marlon became the excuse for Joseph to cram in extra rehearsal time and keep us indoors more. It would turn out there was a deeper reason behind all this, but that would dawn later.

One time there was a step Marlon just couldn’t master and Joseph’s patience snapped. He ordered him outside to get a ‘switch’ – a skinny branch – from the tree outside. We watched as Marlon chose the stick with which we knew Joseph was going to beat him – from the very tree he had used to symbolise family and unity. ‘When you forget,’ Joseph barked, ‘it’s the difference between winning and losing!’ As he struck Marlon on the back of the legs, Michael ran away in tears, unable to watch.

The sight of that switch made us all dig deeper in rehearsals but time and again, Marlon messed up. ‘BOY! Go out there and get a switch!’ Marlon tried to get clever – taking his time to find the skinniest, weakest branch to lessen the impact. ‘NO! You go back out there and get a bigger one!’ said Joseph. Marlon learned to scream louder than it actually hurt. That way, the beating stopped sooner. What Marlon didn’t hear was the talk about turning the Jackson 5 into the Jackson 4.

‘He can’t do it, he’s out of step and out of tune, and he’s ruining our chances!’ Joseph told Mother. But over her dead body was Marlon going to be kicked out and scarred for life: Mother picked her battles, and Marlon stayed in the group.

I’ll say this about Marlon: he’s the most tenacious of us all. He knew his limits but never stopped trying to push beyond them. Whenever we took a break, he kept on practising. He even used the walk to school to rehearse. There we were, a group of brothers ambling to school, and Marlon broke out, dancing on the sidewalk, going through his steps, moving sideways.

From the middle bunk at bedtime, we heard Michael reassuring Marlon – ‘You’re doing good, you’ll get there, keep at it.’ At school, Michael would use break-time to show Marlon spins and different moves. As lovers of Bruce Lee movies, we had our own nunchucks – martial-art sticks – and Michael used to take them to school (rules were more lenient in the days when kids didn’t use weapons to harm one another). Michael and Marlon were like poetry in motion, using the nunchaku techniques to practise fluidity, flexibility and grace in movement. I think this was why Marlon eventually became an accomplished dancer, too – because he put in the extra hours. But Michael hated Joseph using his own excellence as the measure by which he judged his brother. He hated the way that such unforgiving scrutiny always planted doubt: ‘Was that good enough? Was that what he wanted? Did I make a mistake?’ – the early whisperings of a rabid self-doubt that would compel each one of us to worry if our best was our best.

Maybe the resentment this stoked was what lay behind Michael’s rebellion. During rehearsals, if Joseph asked him to do a certain new step, or try a new move, Michael, whose developing freestyle required no instruction, refused. At the age of nine, he had turned from a compliant, ask-me-to-do-anything child into the stubborn kid with attitude. ‘Do it, Michael,’ said Joseph, glaring, ‘or there’ll be trouble!’

‘NO!’

‘I’m not going to ask you again.’

‘NO – I wanna go outside and play!’

Michael became one of those kids who strained against imposed order, pushing his luck more than we ever dared. Inevitably, he received the switch. Time and again, he stood at the tree, crying, trying to choose his branch. Buying time. I remember getting the switch once – for not doing some chore – but Marlon (for errors) and Michael (for blatant disobedience) received it the most.

There were times when Mother felt Joseph was administering his punishment too hard. ‘Stop, Joseph! Stop!’ she begged, trying to make him see through his red mist.

In time, Joseph would learn that the switch was not the most effective man-management tool because it made Michael recoil so far. He barricaded himself in the bedroom, or hid under the bed, refusing to come out – and that ate into precious rehearsal time. Once he screamed in Joseph’s face that he would never sing again if he laid another hand on him. It was left to us, the older brothers, to talk Michael down and coax him with candy: it was amazing what the prospect of a Jawbreaker could do.

Let’s also not forget that Michael was a big tease and it wasn’t all tears and tantrums. If watching The Three Stooges taught him anything, it was how to be silly and he loved to tease. He’d make this face where he opened his eyes real wide, puffed out his cheeks and pursed his lips – and he did this whenever someone was talking all serious. Once, Joseph was lecturing me about a missed chore. It wasn’t serious enough for a spanking, but I had to stand there while he gave me a good talking-to. As he stood across from me – his face thunderous – I spotted Michael behind him, making that face. I tried to focus on Joseph but Michael stuck his fingers in both ears, knowing he’d got me. I started smirking. ‘BOY! Are you laughing at me?’ yelled Joseph. By which time, Michael had darted into our bedroom, out of sight.

He and Marlon even dreamed up a new nickname for Joseph behind his back: ‘Buckethead’. They would say it behind his back, or whisper it when he was near and crack into fits of giggles. We also called him ‘The Hawk’ – because Joseph liked to think he saw and knew everything. That was the one nickname we told him about. He liked it – it sounded respectful.

JOSEPH’S TEMPER AND DISCIPLINARIAN UPBRINGING ARE never going to win much support today, but as I moved through my teenage years, I began to understand the thinking behind the beatings. We didn’t know it at the time, but our parents worried about the growing influence of gang violence in the mid-sixties, which led to a crop of youth gangs. The Indiana Police Department set up its own Gang Intelligence Unit and there was talk at school of automatic weapons and FBI surveillance in the neighbourhood. In Chicago 16 youths were shot in one week, two fatally.

At the Regal Theater, the management went to the extreme of hiring uniformed police officers to patrol the lobby and ticket booths because gangs were terrorising the region. It was this unease and local talk that spread to the ears of fathers at the steel mill. Joseph wasn’t just determined to save us from a life of struggle at The Mill but to keep us from gang involvement – and wrecking our, and his, dream. As he would tell newspaper reporters in 1970: ‘In our neighbourhood, all of the kids got into trouble and we felt that it was very important for the family to involve themselves in activities which would keep them off the streets and away from the temptations of the modern age.’

Gang-bangers preyed on the impressionable (which we all were) and, in a city where the divorce rate was high and kids had little respect for their fathers, gang recruitment brought many kids a sense of belonging, of family, and a chance to earn the love of ‘brothers’. That, and the prospect of something terrible happening to us, was what Joseph dreaded. His dread was heightened when Tito was ambushed on his way home from school and held at gunpoint for his lunch money. The first we knew was when Tito burst through the front door, screaming that some kid had tried to kill him.

Joseph responded by doing two things. He ensured we had a purpose: we had constant rehearsals, which meant we had to come home and couldn’t go out to play. He then turned himself into a greater force of fear. In becoming the tyrant at home, he prevented us submitting to the tyrants on the street. It worked: we were more scared of him than we were of any gang member. Michael noted that Joseph had more patience with us at the beginning, but then his discipline hardened. The timing coincided with the increase in gang violence. Throughout our childhood, we had only ever been encouraged to play with one another and sleepovers with friends were never allowed. Apart from Bernard Gross and next-door neighbour Johnny Ray Nelson, we didn’t really get to know other children.

‘Letting the outside in’, as Mother put it, was fraught with risk because none of us could know what a child from another family might bring in terms of bad thoughts, bad habits and domestic troubles. ‘Your best friends are your brothers,’ she said.

In our minds, ‘outsiders’ were people to be wary of and when you’re raised like that, it can only go two ways: you either become extremely guarded and mistrusting of anyone who isn’t family, or you bounce to the opposite extreme and let anyone in, reacting to the restrictions of the past.

Once the gang threat had become an issue, we were kept indoors more and even kept back from school on the last day of the year because that was thought to be when kids settled scores. Joseph even considered moving us to Seattle ‘because it’s safer there.’ At his hands, we may have seen stars as he beat our asses with a leather belt, the switch and sometimes the broken cord from the iron, but we never saw a knife, a gun, a knuckle-duster, a police cell or a hospital emergency room. I guess Joseph did what he felt was right at the time, in that era, in those circumstances.

TITO AND I REGULARLY WALKED THE fields that led from our house to the Delaney Projects where all the gangs congregated. This was our back route to our new school, Beckman Middle. One day, we saw a police officer standing by a big patch of blood in the snow. We asked him what had happened. He told us we didn’t want to know. But, kids being kids, we pressed him for the answer. He used a long word to make it sound less gory. We took this word home for translation: ‘decapitated’. Someone had been ‘decapitated’. The horror on Mother’s face was matched in the following weeks when I told her that my walk to school wasn’t so bad: the gang-bangers were real friendly and waved, giving us credit for being the Jackson 5. ‘Those boys are not good, Jermaine. You heard what your father said – steer clear of them.’ So the walk to school, through the Projects, with the clothes-lines, abandoned toys and junk wrecks parked up, became a constant head-down-don’t-look-at-anyone exercise.

But then the gangs, and their fights, started encroaching nearer our street. From our front window, we witnessed about three bad rumbles between rival gangs. As the gangs moved in – one coming down 23rd Avenue, the other from the far end of Jackson Street – Mother screamed for us to get inside and shut all doors and windows. Our five little heads must have looked like a row of Afro wigs as we lined up at the window, spying the action.

One time, things got out of hand. Two gangs decided to rendezvous on our corner and school had been abuzz with talk of this showdown. When the day came, we were locked indoors. We knew trouble was near when we heard shouting. And then the pop of a gunshot. That was when we hit the deck. ‘Get down! Everyone down!’ Joseph yelled. Inside the house, the family kissed the carpet. Rebbie, La Toya, Michael and Randy screamed and cried, and Joseph’s face was pinned to the floor, side on, eyes wide. There must have been about two other shots that rang out and we were lying there for about 15 minutes before Joseph checked to see if the coast was clear. ‘Now do you see what we’ve been telling you?’ he said.

From that story, you now know the inspiration behind Michael’s 1985 hit ‘Beat It’ – and the video that begins with two gangs approaching from different ends of the street before he jumps into the middle and unites them with dance.

In an interview in 2010, Oprah Winfrey asked our father if he regretted his ‘treatment’ of us – as if he had been a waterboarding jailer at Guantánamo Bay. It is a question that is easy to ask with a condemnatory subtext in a different age, but had Oprah asked that question in 1965 before a black community pitched into the middle of gangland warfare, she would have been treated as the oddity, not Joseph. It was the way of the world back then. Joseph was a hard man with better managerial skills than fatherly ones, with a heart encased in steel but a dedication driven by good. The only expressed regret was Michael’s. He wished we had known more of the absent father than the ever-present manager. But here’s one irrefutable fact: our father raised nine kids in a high-crime, drug-using, gangland environment and steered them towards success without one of them falling off the rails.

Until I was researching this book, I hadn’t understood the extent of the nonsense written about Joseph’s discipline: that he had once cocked an empty pistol to Michael’s head; that he had locked him, terrified, in a closet; that he had jumped out of the shadows with kitchen knives because he ‘enjoyed terrifying his children’; that he had violently shoved Michael into a stack of instruments; that Michael had had to step over La Toya on the bathroom floor – and then brushed his teeth – after Joseph had laid her out cold. It’s a sad truth of celebrity that when something isn’t officially denied or legally contested, outside commentators feel free to push the boundaries of fantasy until myth is cemented as fact. Whenever I have attempted to place Joseph’s behaviour into a true context, I am accused of being a sympathiser or an apologist, and yet I was there. I saw what really happened – and it doesn’t line up with the portrayal of him as a monster.

People cite to me Michael’s televised Oprah interview of 1993 or the Martin Bashir documentary of 2003. They have heard how the thought of Joseph made Michael feel sick or faint; how Joseph used to ‘tear me up’ and give him ‘a whipping’ or ‘a beating’ and be ‘cruel’ or ‘mean’, and it was ‘bad … real bad’. All of which is true. There is no denying that Michael was terrified of our father and his fear grew into dislike. As late as 1984, he turned to me one day and asked, ‘Would you cry if Joseph died?’

‘Yeah!’ I told him, and he seemed surprised by my certainty.

‘I don’t know if I would,’ he said.

Michael was the most sensitive of brothers, the most fragile, and the most alien to Joseph’s ways. In his young mind, what Joseph did wasn’t discipline, it was unloving. This was reinforced when, after moving to California, new friends (both young and old) reacted in horror when Michael openly told them about Joseph’s actions. ‘That’s abuse, Michael!’ they said. ‘He can’t do that to you. You can report him to the police for that!’ If Michael didn’t think it was abuse before, he did now. Joseph had a big problem in controlling his temper and none of us would raise our children the same way today. But had he truly abused us we wouldn’t still be speaking to him, as Michael was until the rehearsals for the ‘This Is It’ concert of 2009. He had forgiven Joseph and didn’t subscribe to the notion that any of us had been ‘abused’.