По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

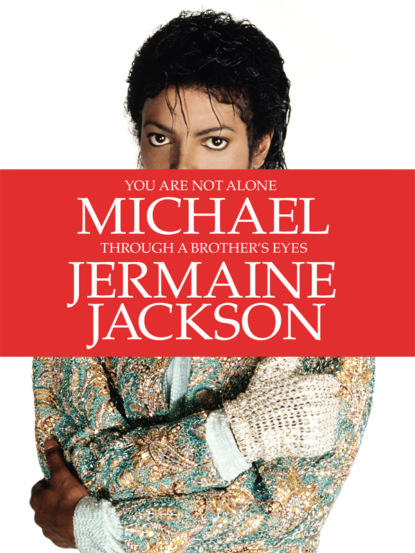

You Are Not Alone: Michael, Through a Brother’s Eyes

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Back in Gary, 1967, Mother was more concerned about who was paying for the studio and copies of the tapes. ‘I am,’ said Joseph. ‘The momentum is just starting,’ he told her again.

I DON’T REMEMBER THE TRUE ORDER of how everything happened next, but the facts are these: Phil Upchurch shared the same manager as R&B artist Jan Bradley. In 1963, she released her hit ‘Mama Didn’t Lie’. The man behind that song’s core arrangement was saxophonist and songwriter Eddie Silvers, formerly of Fats Domino and musical director at a fledgling label, One-derful Records. Within the six degrees of separation, Eddie wrote the song for our demo tape, ‘Big Boy’.

I suspect that Pervis Spann also played a role in this set-up but my memory betrays me. I have no idea why the One-derful label wasn’t interested in us, but the next thing we knew was that Steeltown Records were at the door in the shape of songwriter and founding partner Gordon Keith. When he turned up, Joseph wasn’t overly excited because he was a fellow steel-worker who had established this mini label with a businessman named Ben Brown the previous year. It hardly represented the great dream. But Keith was keen to sign us. Or, as Mother tells it, ‘He wanted you locked into a long-term thing, but Joseph said, “No, we’ve got lots of interest, I’m not doing it.” He was that desperate to sign you that they agreed to the shortest contract – six months.’

Joseph never viewed Steeltown as capable players in the big game, but he saw the value of a recording contract: it would lead to local-radio air time. ‘Big Boy’ was our first single released in 1967. According to Keith, it sold an estimated 50,000 copies throughout the Midwest and New York. We even made the Best Top 20 Singles in Jet magazine. But the greatest moment was when WVON Radio played it for the first time. We huddled around the radio, hardly believing our voices were coming out of that box. It was like the times when you’re handed a group photo and the first thing you do is find yourself and see how you look. It was the same with the radio – we listened for our own voices within the harmonies and background oohs. We had worked damn hard in that living room and suddenly we were being broadcast to most of Gary and Chicago: we were ecstatic.

WITH OUR HEARTS SET ON PERFORMANCE, our academic education seemed almost irrelevant. It was hard to knuckle down when we knew our foundation in life was going to be the stage – and we knew Joseph knew it, too.

School actually made me feel sad because it divided us. It sent us our separate ways into different classrooms or, in Jackie and Tito’s case, different schools. I felt anxious without the brothers around me. I say ‘the brothers’ because we weren’t just siblings, we were a team. I found myself clock-watching, looking forward to the break when Marlon, Michael and I could get together again. Teachers mistook my listlessness for good behaviour so I became a teacher’s pet by default. I was one of those lucky students who didn’t have to try too hard to get B grades. As a result, I was trusted to go on errands – take this or carry that.

I used these ‘office-runs’ as an excuse to take a detour via Michael’s class, just to make sure he was okay. I’d stand in the corridor – with a clear view into his class through the open door, in a position where the teacher couldn’t spot me – and he was always concentrating intensely, head down writing or eyes fixed on the chalkboard. The kid sitting next to him would see me first and nudge him. His eyes darted between me and the teacher – he never liked getting into trouble. When her back was turned, he flashed a quick wave.

Mother found it curious that I checked up on him but, in my mind, I was just the older brother checking up on the younger brother. Doing my duty.

Michael applied himself better than I did at school. His thirst for knowledge was far greater than any of the rest of us. He was that curious kid who asked, ‘Why? Why? Why?’ and he listened to and logged every detail. I’m sure his head had an in-built recording chip for data, facts, figures, lyrics and dance moves.

I always walked Michael to school; he always ran home. The walk home from school mirrored the dynamics of our childhood, showing who was tightest with whom. Michael and Marlon ran around like Batman and Robin. In the street or on the athletics track, Michael always challenged Marlon to races – and always out-sprinted him. Marlon hated being beaten … and then he’d accuse Michael of cheating and they’d start fighting, and Jackie had to break them up. It always puzzled Michael why things had to turn nasty. ‘I won fair and square!’ he’d say, sulking.

Their combined energy was relentless, running around the house, inside and out, screaming, laughing, shouting. That double-act often drove Mother to distraction as she tried to prepare dinner. She’d spin around, grab them in mid-run by both arms and drill her middle knuckle into their temples.

‘Ow!’

‘You boys need to calm down!’ she’d say.

And they did. For about 20 minutes. Then, they would be at the bedroom window playing ‘Army’ – two broomsticks poking out the window, ‘shooting’ at passers-by.

Tito and I were each other’s shadows, too, and Mother dressed us alike, leaving our clothes as the hand-me-down wardrobe for our younger brothers. We used to boss Michael and Marlon, telling them to go get stuff for us, do this and do that, but we tended to give Jackie his space because he was older and crankier, and Randy was the baby brother still curious about everyone and anything.

Out of all of us, people outside the family found Michael hard to figure out because he only came alive in two certain places: in the privacy of our own home, and onstage. He had all this energy and focus when it came to the Jackson 5; no other child could have looked so sure and commanding as he. To watch him on stage was to witness a supreme, precocious confidence but in the school playground he seemed withdrawn until spoken to.

One of Michael’s closest buddies was a boy named Bernard Gross. He was close to both of us, really, but Michael liked him a lot. He thought ‘he was like a little teddy bear’ – all chubby-faced and round, someone who blushed when he laughed. He was the same age as me, but the same height as Michael, and I think Michael liked the fact that an older kid wanted to be his friend. Bernard was the nicest kid. We all felt for him because he was raised by a single mum and we struggled to understand how that could ever feel: the loneliness of being an only child. I think that’s why we embraced him as a rare friend; the one outsider given honorary membership to the Jackson brothers’ club.

Michael hated it when Bernard cried. He hated seeing him get upset over anything and if he did, Michael cried with him. My brother developed empathy and sensitivity at an early age. But Bernard felt for us, too. Once, Joseph told me to go out into the snow to buy some Kool-Aid from the store and I refused. He banged me across the head with a wooden spoon several times. I cried all the way there and all the way back, and Bernard walked with me to make me feel better. ‘Joseph scares me,’ he said.

‘Could be worse.’ I sniffled.

Could be worse. Might not have a father at all, I thought.

ONE OF THE BIGGEST EDUCATIONAL FORCES musically in Michael’s life was the emergence of Sly and the Family Stone. We were inspired to listen to them by Ronny Rancifer, our newly recruited keyboardist from Hammond, East Chicago, an extra-tall body to squeeze into the back of the VW camper van. His lively spirit added to the jovial atmosphere on the road, and he, Michael and I would dream about one day writing songs together. Which was why he made us take a look at the brothers Sly and Freddie Stone, keyboardist sister Rose and the rest of the seven-strong group that blew up in 1966/7 as their posters found their place into our bedroom alongside those featuring James Brown and the Temptations. With tight pants, loud shirts, psychedelic patterns and big Afros, this new group represented a visual explosion and we loved everything about their songs, the lyrics inspired by themes of love, harmony, peace and understanding, as epitomised by their 1968 hit ‘Everyday People’. They brought to the world music that was ahead of its time: R&B fused with Rock fused with Motown.

Michael thought Sly was the ultimate performer and described him as ‘a musical genius.’ ‘Their sound is different, and each one of them is different,’ he said. ‘They’re together, but also strong independently. I like that!’

Like the rest of us, Michael had started to sense that we could match Joseph’s belief. We released one more single on the Steeltown label, ‘We Don’t Have To Be 21 To Fall In Love’, but we wanted more than regional success.

IN THE SUMMER, WE ALWAYS SLEPT with our bedroom window open to feel the cooling night breeze, but this worried Joseph because we lived in a high-crime area. What he didn’t know until we were older was that the chief reason we left it open was for daytime access when we wanted to skip school. Michael was far too well-behaved to take part in such a thing, but when I didn’t feel like class, I’d walk out the front door, peel away from the crowd, hide and return home via the window. I hid in the closet – the den-like hideout space we used – and sat there, or slept, with my stash of candy or salami sandwiches. Tito and I used this space as our hideout for years. Come home time, I’d jump outside and return through the front door.

Eventually Joseph grew tired of yelling about the open window. One night, he waited until we were all asleep, went outside and crept in through the window, wearing an ugly, scary mask. As this large silhouette clambered into our bedroom legs first, five boys woke and screamed the house down. Michael and Marlon apparently just held on to one another, scared witless. Joseph turned on the lights and removed his mask: ‘I could have been someone else. Now, keep the window closed!’

There were a few nightmares in that bedroom afterwards, mainly in the middle bunk, but to suggest – as some have – that Michael was deeply traumatised and scarred by this event is laughable. Joseph always used to wear masks and get his thrills from jumping out of the shadows, creeping up behind us or placing a fake spider or rubber snake in the bed, especially at Hallowe’en. Ninety-nine per cent of the time, Michael found it hilarious, revelling in the scary thrill. If anyone was harmed by the new policy to close the window, it was me: it forced an improvement in my school attendance record.

JOSEPH ENTERED US IN A TALENT contest at the Regal Theatre, Chicago, and we won hands down. We kept returning and kept winning, taking the honours for three consecutive Sundays. In those days, the reward for such a hat-trick was to be invited back for a paid evening performance and that was how we found ourselves sharing a bill with Gladys Knight & the Pips, newly signed by Motown Records.

At rehearsals, we were midway through our routine when I looked to the wings to find the usual sight of Joseph accompanied by the unusual sight of Gladys Knight. As she tells it, she ‘heard some performance, jumped up and said, “Who is that?”’ When we came offstage, Joseph told us that she wanted to meet us in her dressing room. It was a big deal because she and the Pips were all the rage, having broken into the charts the previous year with their No. 2 hit ‘I Heard It Through The Grapevine’.

We shuffled into her room, led by Joseph. I don’t know what she must have thought when five shy brothers walked in, considering the performance that had grabbed her attention. Michael was so small that when he sat down on the sofa, his legs dangled off the end.

‘Your father tells me that you boys have big futures ahead of you,’ she said.

We nodded.

Gladys looked at Michael. ‘You enjoy singing?’

‘Yeah,’ said Michael.

She glanced at the other four of us. We all nodded. ‘You boys should be at Motown!’

That was the night Joseph asked Gladys if she could get someone from Motown to watch one of our performances. She promised she’d make that call, and she couldn’t have been more sincere.

Back home, Joseph told Mother that it was only a matter of time before the phone rang. But it never did.

As it turned out, Gladys was as good as her word because we later learned she had called Taylor Cox, an executive at Motown, but there was no interest higher up the ladder. Berry Gordy, the founder of the label, wasn’t looking for a kid group. He’d been there, done that with Stevie Wonder, and he didn’t want the headache of hiring tutors or the Board of Education’s restrictions on working hours.

Meanwhile, Joseph kept us on the road and we kept plugging away at the Regal and places like the Uptown Theater, Philadelphia, and the Howard Theater, Washington DC. Our road led towards ‘The Chitlin’ Circuit’ – the collective name given to a host of venues in the south and east of the country, showcasing predominantly new African-American acts. These were our ‘roughing-it years’, when the professional stage educated us in the dos and don’ts of live performance. And all the time, we just kept performing and pushing our Steeltown 45s.

CHAPTER FIVE

Cry Freedom

‘IF THEY LIKE YOU HERE, THEY’LL like you anywhere,’ Joseph said, in the van en route to New York City. Destination: the world-famous Apollo Theater in Harlem – a place ‘where stars are made’.

All the way from Indiana, he talked up a storm about what this venue meant and the singers who had triumphed here: Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, tap-dancer Bill ‘Bo Jangles’ Robinson … and James Brown. In an era when black faces on television were still relatively rare, the Apollo was the platform for African-American acts. ‘But if you get it wrong, make a mistake, this audience will turn on you. Tonight, you have to be on your game,’ he continued.

We honestly weren’t intimidated: we knew that winning over the crowd meant we’d be walking through a door towards bigger things, so what greater motivation could there be for young boys with a dream? Sometimes there were benefits to being lambs in the entertainment industry – our innocence made us blind to the enormity of certain occasions. We pulled up beneath the Apollo sign, which hung vertically, lit sunset orange at night.

When we first went in, the walls were lined with the photographs of legends. We walked the corridors and then noticed the shabby carpet. Joseph asked us to imagine the feet that had worn it away; to imagine the kind of shoes we were walking in. We had our own dressing room with a mirror surrounded by light-bulbs and a chrome clothes rack on wheels. And the microphones popped up electronically from beneath the stage, all space age.

Inside our dressing room, Michael stepped up on a seat with Jackie and pushed up the window to look out. ‘There’s a basketball court!’ shouted Jackie. That brought a new burst of excitement. We wanted to get outside and shoot some baskets, but then Joseph walked in. Everyone jumped into line and pretended to be focused again. Time to get serious. I don’t know if Joseph ever realised how nonchalant we were on the inside about performing, but he knew Harlem wasn’t Chicago. The Apollo crowd was well versed in entertainment: it knew its music. If things went badly, disgruntled murmurs grew into boos, followed by missiles of tin cans, fruit and popcorn. When things went well, they were up on their feet, singing, clapping and dancing. No one walked off the Apollo stage and asked, ‘How did I do?’

Before going on, we sensed the buzz of a full house. Michael and Marlon stood in front of Tito, Jackie, Johnny and me in the shadows and whoever was on before us wasn’t getting the greatest reaction. The boos were loud and unforgiving. Then a can landed onstage, followed by an apple core. Marlon, startled, turned to us. ‘They’re throwin’ stuff!’

Joseph looked at us as if to say, ‘I’m telling you …’

Between the curtains, backstage and hidden from public view, there was a section of tree trunk. It was the Apollo’s ‘Tree of Hope’ chopped from a felled tree that had once stood in the Boulevard of Dreams, otherwise known as Seventh Avenue, between the old Lafayette Theater and Connie’s Inn. In an ancient superstition, black performers touched that tree, or basked beneath its branches, for good luck. It had come to symbolise hope for African-American acts in the same way that the tree outside our home symbolised unity. Michael and Marlon duly stroked the ‘Tree of Hope’, but I don’t think Lady Luck had anything to do with the performance we gave that night.

We rocked the Apollo and the crowd was soon on its feet. I don’t think we brought a finer performance to any venue in our pre-Motown days and we ended up winning the Superdog Amateur Finals Night. We must have impressed management because we were invited back … this time as paid performers. That May of 1968, we were on the same bill for an Apollo night with Etta James, the Coasters and the Vibrations. We knew we’d done good at the highest level. What we didn’t know was that a television producer had been sitting in the audience, taking notes and developing a keen interest.

A SHORT JEWISH LAWYER WHO ALWAYS wore suits arrived on the scene. Apparently Richard Aarons had knocked on Joseph’s hotel-room door in New York and sold his services. We were introduced to the debonair and playful Richard as the man ‘who is helping us get to where you need to be.’ As the son of the chairman of a musicians’ union in New York, Richard had useful connections.