По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

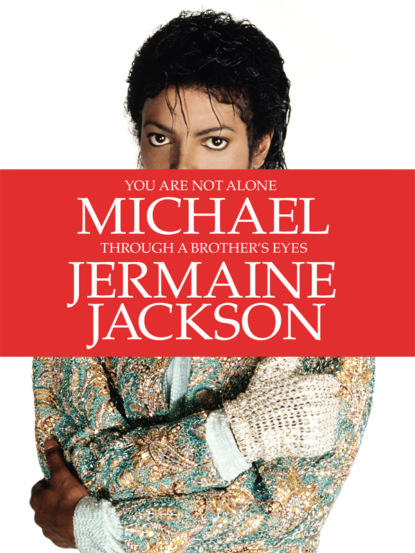

You Are Not Alone: Michael, Through a Brother’s Eyes

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As children, we sensed that struggle to make ends meet. Our parents’ combined take-home pay was about 75 dollars a week. They were too proud to claim welfare, so in the winter, Tito and I shovelled snow from neighbours’ driveways to put some extra money on the table. We always knew when Joseph had collected his pay packet because a new loaf of bread was on the kitchen worktop, with a packet of luncheon meat. On more than one occasion, Joseph was laid off and then hired again. During those lulls, he got work picking potatoes. We instantly knew when the steel shifts had dried up because all we ate was potatoes – baked, mashed, boiled, roasted.

Inland Steel was the end of the rainbow for generations of families. It was said there were only three outcomes to life in Gary: The Mill, prison or death. The last two options were related to the gang-life that was the flip-side to our community. But whatever destiny seemed laid out for us, Joseph was determined to change its course. Every hour he worked was with that in mind. Our escape was his escape, with Mother.

JOSEPH WAS ONE OF SIX CHILDREN: four boys, two girls. As the eldest, he was closest to the sister who followed him in order of birth: Verna Mae. Our sister Rebbie reminded him of her, he said – dutiful, kind, the proper little housewife, and wise beyond her years. Joseph loved how Verna Mae took care of the house and children. He remembers her, aged seven, reading bed-time stories to their brothers Lawrence, Luther and Timothy, by oil lamp. Then she fell ill and Joseph could do nothing to help her. The doctors couldn’t even diagnose what was wrong with her. From her bed, Verna Mae was stoical. ‘Everything is well. I will be healthy again,’ she said. But Joseph watched his sister’s deterioration from the bedroom door as the adults surrounded her bed. She succumbed to the illness and passed away. Joseph sobbed for days, unable to comprehend such a loss. As far as my understanding goes, that was the last time he shed a tear: he was 11.

As self-confessed cry-babies, Michael and I always hated how hardened our father was. None of us can remember a time when we saw him show any emotional vulnerability. Whenever we cried as kids – even after he had chastised us – he berated us: ‘What you crying for?’

Joseph had spent his formative years mourning and missing his sister. At her funeral, after walking behind the horse-drawn cart that carried her coffin, he vowed he never wanted to lay eyes on anyone’s tomb again. One loss in life sealed our father’s emotions and Joseph kept his word: he never attended another funeral. Until 2009.

WHEN JOSEPH WAS A SCHOOLBOY, HE was terrified of one woman teacher. The ‘respect thy teacher’ decree carried extra force because his father, Samuel, was a high-school director and believed in strict discipline by corporal punishment. This fearsome woman apparently scared Joseph so much that he shivered whenever she called out his name. Once, so the story goes, he was called out to the front of the class to read from the chalkboard. He knew exactly what the words were, but fear left him mute. The teacher asked him again. When he couldn’t answer a second time, the punishment was swift: a wooden paddle board across his bare behind. This thing had holes in it, too, for extra suction with each whack. As she paddled him, she reminded him why he was getting hit: he had disobeyed her when he didn’t read. He hated her for it, but respected her too. ‘Because of this, I listened to her and always did my best,’ he said.

It was the same when Papa Jackson chastised him. That was how he was raised – on the old theory that in order to control someone, you first need to shock fear into them. This was his lesson in life, marked out on his backside. In later weeks, that same woman teacher held a talent contest and pupils were invited to do anything they wished: art, poetry, craft, a short story, a dramatic presentation. Joseph wasn’t artistic; he wasn’t good with words – he’d only ever watched silent movies. He knew only one thing: the sound of his father’s voice, singing ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’. So he decided to sing, but when it came to his turn, he shook so much that his pitch was quivery and rushed – and the whole class burst out laughing. He returned to his desk ‘humiliated’ and expected another beating. When his teacher approached, he cowered. ‘You sang very well,’ she said. ‘They are laughing because you were nervous, not because you were bad. Good try.’

On the walk home from school, Joseph says he made a vow to himself that ‘I’ll show ’em’ and he started dreaming about ‘a life in show-business’. I didn’t know that story until recently. He excavated it from his past, trying to apply meaning after the event. I don’t suppose any of us Jacksons have taken the trouble to understand our deepest history, or even talk about it too much. Michael once said he didn’t truly know Joseph. ‘That’s sad for a son who hungers to understand his own father,’ he wrote in 1988, in his autobiography, Moonwalk.

I think there is something unknowable about Joseph. It’s difficult to reach him beyond his barriers, perhaps built by a fear of loss and reinforced by his need for respect. None of us can remember him holding or cuddling us, or telling us, ‘I love you’. He never play-wrestled with us, or tucked us into bed at night; there were no heart-to-heart father-son discussions about life. We remember the respect, the instructions, the chores and the commands, but no affection. We knew our father as he was; someone who wanted to be looked up to, and to provide for his family – a man’s man.

Acceptance of this was to know him in its limited way, and as much as Michael struggled to accept the way Joseph was, he always had compassion for him, not judgement. The sad thing is that I don’t think he knew the back-story I have just shared. I guess many people only know their parents as ‘Mother’ and ‘Father’ and not as people prior to that role but if we understand more about our parents when they were young, then maybe we have a better chance of knowing who we become. I like to think that the stories about Joseph’s schooldays explain quite a lot.

JOSEPH DIDN’T NEED TO DAY-DREAM ABOUT a life in California, like most working men in Indiana: he had already whetted his appetite by living there. That was why his horizons were set somewhere between the sunsets on the Pacific and dreams of the Hollywood sign. Aged 13, he moved from Arkansas to Oakland on San Francisco Bay, via Los Angeles, by train. He moved with his father, who quit teaching for the shipyard after discovering that Joseph’s mother, Chrystal, had had an affair with a soldier. Initially, Samuel Jackson went alone, leaving Joseph behind. Three months later, after pleading letters from son to father had gone back and forth, Joseph made the ‘toughest of choices’ and moved west. More letters went back and forth, this time between Joseph and his mother. Our father must have been persuasive even as a kid because some months later, Chrystal Jackson left her new man and returned to the husband she had recently divorced.

The arrangement lasted a year before she headed back east to set up a new life with another man in Gary, Indiana. I suspect Joseph felt like the rope in a tug-of-war being pulled by both parents. For a man who has forever preached ‘togetherness and family’, I don’t know how he stood it. All I know is that he first pitched up in Gary after taking the bus all the way from Oakland. On arrival, he thought the city ‘small, dirty and ugly’ but his mother was there and reading between the lines, I think he detected a small sense of ‘celebrity’ around him. Here was a kid not from Arkansas but from California, and his stories of West-Coast life brought a lot of attention from the local girls. So, aged 16, Joseph moved to be with his mother in Gary, Indiana but in his mind, he would one day return to California. ‘We’ll go out West. Wait till you see it out West,’ he used to say to us – an explorer on stopover from some great adventure he had yet to resume.

Joseph’s face was lined and furrowed by his years of hard work, and he had thick eyebrows that seemed to cement a permanent frown, hardening the hazel eyes that looked right through you. One glare was enough to make us wobble as children. But talk of California softened his features. He remembered ‘the golden California sunshine’, the palm trees, Hollywood and how the West coast ‘was the place to be in life.’ No crime, tidy streets, opportunities to get on top. We watched the television series Maverick and he pointed out streets he knew. Over the years, we constructed this city into a fictional paradise – a distant planet: when man could walk on the moon, we could also perhaps visit LA. Whenever the sun was setting in Indiana, we always said to each other, ‘The sun will be setting in California soon’: we always knew that there was some place, some life, that was better than what we had.

LONG BEFORE MICHAEL WAS BORN, AND while Mother was pregnant with me, Joseph first conceived a plan of ‘making it’. As a guitarist, he formed a blues band named the Falcons with his brother, Luther, and a couple of friends. By the time I came along, they had built up a slick act, performing at local parties and venues to put some extra dollars in their pockets. While he was working the crane, Joseph composed songs, shifting steel beams on auto-pilot and conjuring lyrics as a singer-songwriter.

In 1954, the year I was born, he claims to have written a song called ‘Tutti Frutti’. One year later, Little Richard released a same-titled hit. When we were growing up, the story of how Little Richard ‘stole’ our father’s song became legendary. It was never true, of course. But all that was important was that a black man from the middle of nowhere had created a song that redefined music – ‘the sound of the birth of rock ’n’ roll’. It was that possibility that locked deep in our minds every time the story was told.

I don’t remember vividly the Falcons rehearsing, certainly not when measured against what ‘rehearsing’ would come to mean for us! But I have a vague memory of Uncle Luther – always smiling – arriving with packs of beer and his guitar, then riffing with Joseph as we sat around, sucking it all in. Uncle Luther played the blues and Joseph switched between his guitar and the harmonica. Those were the sounds that sometimes helped us drift off to sleep.

Joseph’s musical dream floundered when the Falcons disbanded after one of them, Pookie Hudson, quit to form a new group. But Joseph still came home and unwound by playing his guitar, then putting it away in its usual spot at the back of his bedroom closet. Tito, the first budding guitarist among us, eyed that closet like an unlocked safe containing gold but we all knew it was Joseph’s pride and joy. As such, it was untouchable. ‘And don’t even think about getting out my guitar!’ he warned us all before leaving for work.

WE FIVE BOYS SHARED ONE BEDROOM – the best dressing room we ever shared. Within this confinement, we grew up as best friends. Brotherhood grows stronger each year. We are the only ones who can ever say to one another, ‘Remember how we were. Remember what we shared. Remember where and what we came from.’

Or, as Clive Davis would later tell me, ‘Blood is thicker than mud.’ We were inseparable in Gary, forever together, night and day. We shared a metal-framed three-tiered bunk-bed. Its length was just big enough to fit against the back wall and its height meant that Tito and I slept head to toe, about four feet from the ceiling. In the middle were Michael and Marlon, and Jackie had the lowest bunk all to himself. Jackie was the only brother who didn’t know what it was like to wake up with a foot in his eyes, ear or mouth. The girls, Rebbie and La Toya, slept on the sofa-bed in the living room (later joined by our brother Randy and baby sister Janet) so every room was crammed to its limit. Imagine being Rebbie – the eldest child – and never once having a bedroom to herself!

As brothers, we spent a lot of time in our bedroom, with its one window looking out on to 23rd Avenue. Every night felt like a sleepover. We went to bed at roughly the same time – 8.30 or 9pm – regardless of age and hurled pillows, wrestled and talked up a storm for a good hour before sleep, planning on what we’d be doing the next day.

‘I got the skates, so I’m the one roller-skating!’

‘I got the bat and ball, who’s playing?’

‘We’re building a go-kart. Who’s in?’

We ripped the sheets from the bed and threw the mattresses on the floor, and built Greek columns out of books, draping sheets over them to create a tented roof. We loved sleeping on the floor in our self-built ‘dens’. We loved sleeping on the floor even when we hadn’t built a den – it felt like camping out.

Come the morning we were each other’s alarm clocks. ‘You awake, Jermaine?’ I’d hear Michael ask in a loud whisper. ‘Jackie?’ We’d wait for the reply that rarely came because he always liked his extra ZZZZ.

Then came the chaos of the ‘15-minute bathroom’ rule. As one brother or sister darted out, another darted in and then we heard Mother shout: ‘JERMAINE! Your 15 minutes is up!’

I loved mornings at home. I loved the chaos in the kitchen, and I loved making harmonies in bed when we woke. We didn’t need to see each other’s faces, we just lay there singing. We always sang, even during chores like painting the house, doing the laundry, cutting the grass, or ironing. Our self-entertainment eased the tedium and we ‘covered’ hits from sounds we heard at home: Ray Charles, Otis Redding, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, and Major Lance (whose keyboardist was an unknown man called Reggie Dwight, nowadays better known as Sir Elton John).

Michael often recalled the ‘joy’ and ‘fun’ we shared in our tiny bedroom. I think he yearned to have those days back; to have brothers ‘sleeping over’. He always said that he missed the company of brothers around him. As grown men, whenever we had a family meeting or a brotherly catch-up, we all convened in the smallest room. We did this unconsciously for years until it was pointed out that it was, perhaps, a bit strange to meet in the smallest room at places like Neverland or Hayvenhurst. Something within each of us obviously enjoyed feeling close and confined with the others. It felt natural; it always felt like ‘home’.

Something else we didn’t realise until adulthood was that Mother and Joseph had lain in their bedroom just across the way listening to us sing through the walls, from 3-year-old Michael to Jackie aged 11. ‘We heard you singing all night, we heard you singing in the morning,’ said Mother. But even then I don’t think Joseph heard the distant drumbeat of his California dream. That didn’t happen until the day Tito broke his prized guitar – and then we had to sing for our lives.

JOSEPH OWNED A DARK-BROWN BUICK THAT looked like an angry fish coming at you. The configuration of the headlights, the grille and the V-shaped rim of the hood was like one big scary face frowning and baring its teeth. I don’t know if they made cars with engines that purred back then, but that car – just like Joseph himself – definitely did not purr.

It seems comical, looking back, that this ‘angry fish’ was our warning system that our father was minutes from home. We’d be out in the street playing when one of us would spot the cruising scowl in the distance and shout, ‘Clean the house! Clean the house!’ We’d drop everything and bolt inside, cleaning up our room faster than Mary Poppins ever could. In the rush, we grabbed all our clothes and shoved them into one great pile in the closet or stuffed them into drawers, unfolded and out of place. We were brought up better than that, Mother always said, when she found clothes bundled into a bed-sheet and hidden away. But all we wanted to achieve was the appearance of neatness: so long as everything looked good on the surface, we were fine. We also knew that, while we were at school, Mother would go into our bedroom, pull out everything, refold our clothes, restore order and say nothing.

It was no surprise to her that Michael and I grew into the kind of men who left clothes on the floor where we stepped out of them but we cited the same defence: when you grow up as brothers in one tiny room, you get used to knowing where everything is in the chaos or clutter. We got away with a lot more things with Mother. Don’t get me wrong, she was strict, too: if we misbehaved, she wasn’t afraid to administer a firm slap around the ear with the palm of her hand. But where Mother had patience, Joseph had a short fuse trip-wired by another hard shift at The Mill. We heeded what Mother said: respect that your father is in the house, respect that he’s had a hard day at work, respect that he doesn’t want to hear noise.

When he arrived home, Respect walked through the door and the air in the house stiffened. His basic rule was simple: I’ll tell you something once and if you have to be told again, you’ll be punished. As kids within a growing family, we regularly had to be told again. Jackie, Tito and I knew from sore experience what the consequences were. Michael and Marlon, as infants, felt our fear vicariously – at first. When Joseph got angry, just one look on his face was enough – he didn’t need to say a word. He had a mole the size of a dime on one cheek and I can still see it in my mind, close up: whenever he got really mad, it and his face crunched up – the storm clouds rolling in before the clap of thunder and the dreaded words ‘WAIT FOR ME IN YOUR ROOM!’ followed by the flash of lightning; the eye-watering sting of a leather belt against skin. We normally received 10 ‘whops’. I call them ‘whops’ because that was the exact sound the belt made as it whipped the air. I screamed out for God, for Mother, for mercy, and anyone else’s name that I could think of, but Joseph just shouted louder, reminding us why we were being punished: the discipline followed by the reason, mimicking his lessons as a schoolboy.

Whenever we were punished, our screams were what Michael heard, and he saw the red marks and belt-buckle imprints on bare skin at bedtime. This made him fear something long before he actually felt it. In his mind, the mere thought of Joseph’s discipline was traumatic. That is what exaggerated fear does: it builds something in the mind to a scale that, perhaps, it is not.

A WHITE MOUSE HAD BEEN RUNNING loose around the house and Joseph was desperate to catch it because it was driving the girls crazy. When we heard them scream, we knew this rodent had scurried in for a visit. An exasperated Joseph couldn’t understand why we suddenly had this problem. What he didn’t account for was the start of Michael’s lifelong affinity with animals.

Unknown to any of us, he’d been treating this mouse like a pet, encouraging its visits with bits of lettuce and cheese. Looking back, it was obvious: whenever Mother screamed and Joseph cursed, Michael fell suspiciously quiet and slid away. He was only three: who was going to suspect his cunning? But it was only a matter of time before he was found out. That moment arrived when Joseph crept into the kitchen and caught him red-handed, kneeling on the floor, feeding the mouse behind the fridge.

The house shook when Joseph bellowed, ‘WAIT FOR ME IN YOUR ROOM!’

What Michael did next surprised everyone.

He bolted.

He started running around the house like a terrified rabbit. Joseph chased him with the belt and grabbed the back of his shirt, but my brother was a flexible, agile little dynamo, and he wriggled and fought and pulled his arms out of the sleeves, and ran on. He darted into Joseph’s room, up and over the bed, and pinned himself against the wall, tight into the corner, knowing the belt’s arc couldn’t reach him without first striking the walls.

I hadn’t seen Joseph so angry. He dropped the belt, grabbed Michael and spanked him so hard that he screamed the house down.

I hated the awkward silence that hung in the air after one of these episodes, broken only by Mother’s murmurs of disquiet and the quiet sobs into the pillow of whichever one of us had got hit.

Michael didn’t help himself because he was the most defiant. Rebbie remembers the time when he was 18 months old and tossed his baby bottle at Joseph’s head. That should have put our father on notice because when Michael was four, he threw a shoe at him in a temper tantrum – and that earned him a good spanking, too.

Michael’s fear of a spanking always sent him running. Sometimes he’d do a sliding dive under our parents’ bed and tuck himself against the back wall in the centre, gripping the bed springs. It was an effective tactic because after half an hour under there, Joseph was either too exhausted to care or had calmed down: Michael got away with a lot more than he ever let on.

TITO’S PASSION FOR THE GUITAR COULDN’T help itself.

As Jackie and I started learning songs from the radio, his talent blossomed through lessons at school. But when he was at home, he couldn’t practise. So, despite all warnings from Joseph, he borrowed our father’s guitar from the back of his closet. What he wouldn’t know couldn’t hurt him, right?

Whenever Joseph worked, Tito seized his moment. He started playing and we began making harmonies. On a couple of occasions, Mother walked in and found us out, but apart from a gasp that told us we were playing with fire, she turned a blind eye. She was a lot more lenient than our father. On one particular weekend, Tito started playing and we were singing some Four Tops’ song. He was sitting there, plucking away, and Jackie and I were crooning when suddenly there was a twanging noise. Tito went white when he realised one of the strings had broken. ‘Oooh, you’re going to get it now!’ squealed Jackie, part excitement, part fear.

We’re all going to get it now, I thought.

We put the broken treasure back in its rightful place and were sitting in our bedrooms when we heard his car pull up. The bomb was primed. Each loud footstep on the linoleum matched what was going on inside our ribcages. One … two … three … ‘WHO’S … BEEN MESSING … WITH MY GUITARRRR?’ He hollered so loud I think they heard him in California. When he pounded into our room, Michael and Marlon scarpered, leaving Jackie, Tito and me standing by the bunk-beds already whimpering over what we knew was coming next. Mother tried intervening, claiming it was all her fault, but Joseph wasn’t listening. We cried even louder when he told us we were all going to get it until one of us owned up.

‘It was me,’ Tito said, barely heard. ‘I was playing it –’ Joseph grabbed him ‘– but I know how to play. I KNOW HOW TO PLAY!’ he screamed.