По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

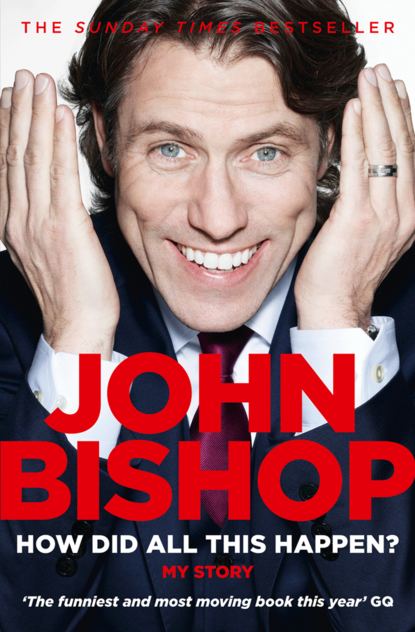

How Did All This Happen?

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Those in charge with selecting the team were taking a long time to do it, however. They were huddled over clip boards and team sheets, so Mr Hilton told me to take the opportunity of a lift home from my friend’s dad so I could get warm. ‘You did well,’ he said. ‘I’ll call you with the good news later.’

A few hours later he phoned the house to tell me I had not got in. It was the biggest disappointment of my life, and I locked myself in the bathroom till the tears subsided. On the phone he sounded as disappointed as I was, explaining that the teachers picking the team were from a private school in Chester, and that the majority of the squad selected came from their school. It was just another example of how money can buy you opportunity.

Years later, my youngest son, Daniel, played against that same school in the final of a schools cup. The Chester school had consistently won the cup in previous years; Daniel’s school had never even reached the final before. And yet they won. At the final whistle I nearly ran onto the pitch to complete the revenge by waving my victorious fist in front of the Chester school children, parents and staff. Thankfully, common sense told me that as my feelings of being wronged had occurred some thirty years earlier it was unlikely to have involved anyone on the other side of the pitch. Even so, the fact that their official school photographer was reluctant to take a team picture of our boys suggested to me that it was still an institution of tossers.

Mr Hilton had been very supportive in all my school years, using the leverage of the football team to ensure I kept up my schoolwork and didn’t drift, as some of the other lads did.

In the final year the team was good enough to get into a number of the local finals, and I always felt I let Mr Hilton down when I was sent off during one final for punching the centre-half from a school in Helsby. Even to this day I don’t know why I did it: perhaps it was because the lad had long hair and a beaded necklace and looked much cooler than me – he just seemed to irritate me to the point that I punched him. It wasn’t even a good punch, but what hurt more is the fact that I had let Mr Hilton down. I was 16 at the time and I never managed to apologise properly. So if he reads this, I just want to say, ‘Sorry, sir.’

5. Mr Logan: an English teacher who had encouraged me, along with my other English teacher Mrs Withers, through my O-levels in English Language and Literature. He talked me into returning to school when I had left, basically altering the whole course of my life – and that is no exaggeration.

6. Ms Philips: the headmistress of the comprehensive school who bent the rules to allow me to do A-levels and to comply with Mr Logan’s plans for me.

There were other teachers who had more contact with me during my school life and who had more direct influence on me, but that decision, taken with no small consequence, changed the world for me. I will be eternally grateful to both Mr Logan and Ms Philips.

7. Mr Debbage: the teacher who became a friend by giving me somewhere to live when I first moved to Manchester, but who also guided me through my History O-and A-levels, giving me a love of the subject I still retain to this day. He left teaching, as many skilled people do, to move into other areas and effectively became a professional card player. But Bridge’s gain was education’s loss, because he was the most brilliant of teachers, particularly at A-level standard, where he wasn’t having to fight with a room full of varying degrees of interest and intellect, which is the challenge teachers – particularly those in the comprehensive system – face.

8. Miss Boardman: my class tutor through all of my senior-school years. We saw her every day, and it is impossible for someone like that not to have an influence on you. She was only a few years older than us: for many of the teachers in the school it was their first job and they were roughly 8 to 12 years older than the pupils. That is a lot when you’re 11, but it’s not so much when you’re 16. She died too early. I managed to go to her funeral, which was both a sad and a celebratory affair, and I was glad I went. Let’s be honest, you don’t go to a teacher’s funeral unless they meant something to you, and she did.

I am not suggesting this is my Goodbye, Mr Chips moment, but I do feel teachers need to be celebrated. So thank you to all the ones who have been in my life. Thanks, too, even to the ones I didn’t like or who were rubbish at their job. You taught me something: the valuable lesson that some people in authority are pricks.

My education became disrupted as I entered the final year of junior school due to an operation I had on my left leg. At the time I was playing a lot of football, and the GP suggested quite reasonably that the pain in my leg must be ligament damage. As a result, his treatment was rest and a compression bandage.

However, the pain became unbearable after a few weeks and, despite the rest, there seemed to be no improvement. As I was unable to walk, my mum had to wheel me up and down the hill to the GP practice balanced on my bike, to ask if there was any other possible explanation. On many occasions they made the mistake of saying no, until she insisted I be referred to hospital.

Eventually, the referral to the hospital was made. I remember the day the ambulance came to collect me. Just as it arrived, I was sick, either with fear or illness. I don’t recall very much of what happened after that, apart from being prepared for surgery with my mum and dad standing either side of the bed, and my dad leaning in to kiss me on my forehead.

This was at a time when we were years past kissing: goodnight was a nod to my mum and a handshake to my dad – I’m glad to say that my family is so much more demonstrative now than we were then. One thing I have learnt from my travels over the years is that the British approach to displaying affection needs to improve. Now, when I see my mum and sisters and female family members or friends, we always kiss – although London-based females confuse me easily with the one or two cheek thing. Personally, after one cheek, if you are going again, you may as well throw the tongue in.

Eddie, my dad and all male family members get a handshake. Indeed, after a night in a bar with a few dozen Romanian miners (which I will come to later), I always shake hands with any male group I am in. It’s good manners, it breaks down barriers, and I think it shows some class – which is something you don’t always expect to learn from men who spend most of their time down a hole.

Lying on a hospital trolley about to be operated on and having both parents kiss me on the head made me start to think something was wrong. Which it was. Upon arrival at the hospital, my leg had been X-rayed and checked by the aptly named Mr Bone. Mr Bone had diagnosed a condition called osteomyelitis, a bone infection which he said was akin to having an abscess inside my left femur, the size of which, he informed my parents, was a huge cause for concern. He then advised my mum and dad that the next 24 hours would be critical.

In his words, he was operating to try to save my leg, although he told them if the operation was at all delayed and the abscess burst, then it could potentially become systemic. After that, there was a real danger I would die.

His plan was to try to drain the poison out of my leg, although he felt that the damage caused was already such that my leg would probably never grow beyond its current size – I was 11 at the time. It would then either be such a hindrance that I would want it amputated, or I could live a decent life with a built-up shoe.

Of course, I knew nothing of this when my mum and dad kissed me.

Luckily the operation was a success, but I did require a month in hospital and six months with a walking stick, followed by visits to the physiotherapy unit for a further three years, till they were satisfied that the leg was growing in tandem with the other one. I quite enjoyed having the walking stick, which I used to throw for Lassie to chase until I realised she would never bring it back. There is nothing more pathetic than chasing your own dog for your walking stick, when you need a walking stick to walk.

When I was eventually signed off by the physiotherapy department some three years after the operation, I knew how lucky I was. The final sign-off meant that they believed I was fixed for life, and in reality I was: I have never had any problems with my leg, and after the rehabilitation period I was able to do everything as if it had never happened. Yet I knew that not everyone was that fortunate.

During my time in hospital I became aware of a boy in the same ward as me. He had visitors, but he never really noticed them as he lay looking at the ceiling. Sometimes his mum would just sit on a chair next to his bed and cry; other times, she would come with a priest who would administer Holy Communion, but all the time he just lay looking up, communicating using weak flicks of his eyelids.

His name was Kieran, and when I was able get out of my bed I started going over to him with my cartoons. My leg at this point was attached to a drip, which was pumping antibiotic fluid directly into the bone, with another bag to collect the putrid, black-red infection as it drained. I was not able to move all over the ward, but I could make it to the other side of the room to his bed – it only took me around 15 minutes. When the nurses saw that I was visiting Kieran, thankfully they moved his bed next to mine.

Kieran and I became good friends, mainly because we were the only ones in there for more than a few days and because we were very close in age. I would read comics with him or just talk, or show him things. Gradually his winks were accompanied by grunts, and it was clear he was on his way back from the damage that had been caused when he had been knocked over by a van whilst out playing.

When I left hospital I was genuinely sad to be saying goodbye to Kieran. We kept in touch and, during my frequent visits to the hospital, I called in to see him on the ward and later at his house, when he had been deemed well enough to be transferred home, near Warrington. When my hospital visits ended and I had no reason to visit Warrington, our communication reduced to the odd letter or card, and a very occasional phone call, although his speech still had some way to go to be fully comprehensible and his handwriting looked like it had been a struggle to complete the words.

Then, one morning, when I was getting ready to go to school, my dad opened a letter over breakfast. I recognised the handwriting as belonging to Kieran’s mum. I could see from his expression that my dad had a message to pass on. He handed me the letter. Kieran had died. Despite his improvement he hadn’t been strong enough to ward off normal infections and had lost his fight for life.

Kieran had died as a consequence of an accident that could have been avoided. As always with these happenings that can ruin lives, there would have been many nights spent by all involved wishing that those split-second decisions that had put Kieran in front of that van had been different. Like my school friend in the swimming pool.

I was 17 and, once again, I was reminded that nothing in life is guaranteed.

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_5fa05818-ef8c-5874-8427-4c892bf1fde5)

TEENAGE KICKS (#ulink_5fa05818-ef8c-5874-8427-4c892bf1fde5)

I have teenage boys now. I look at their life and not only do I not understand them because they are teenagers and their job is to be incomprehensible to their parents, but also because their life is nothing like the life I had at their age. When I was a teenager, we did not have any form of communication apart from talking either face-to-face, being on the house phone or writing. Admittedly, the letter-writing side was in reality limited to notes around the classroom, usually involving a very poor caricature of the teacher with enormous genitals. Which now seems rather odd. Why would it be funny to suggest the man in front of you had a huge cock? But, for some reason in a world before YouTube, it was the funniest thing we could think of.

Valentine’s Day cards were the only other time I recall writing to communicate. They were things to be prized, and size certainly mattered. During my teenage years I would give my girlfriend a Valentine’s card that was the size of a Wendy house, or padded so it was like a duvet in a box, although admittedly a duvet with a doe-eyed teddy bear on it. I wouldn’t for a minute suggest that I was in any way more romantic than any other teenage boy, but from an early age I learnt that you have to invest if you want something, and an impressive card, in my mind, stood you in good stead for a fondle.

I sometimes miss the simplicity of teenage relationships, though – the ability to end it by telling your mate to tell her mate that she was ‘chucked’ just seems so much more honest in its own cowardly way than the text/Facebook route chosen by teenagers today. I also miss the progressive nature of the physical relationship. The gradual stages of fumbling and endless snogging to suddenly being allowed entry into unchartered waters so that you take another tiny step towards manhood – all of that held an excitement that is hard to replicate at any other stage of your life. A mate of mine said to me that reducing his golf handicap was giving him the same buzz that he received from achieving the gradual progression through the bases when he was a teenage boy. There is nothing that can define you more as a middle-aged man than having a friend who is as excited by lowering his golf handicap as he once was by learning how to undo a bra. Age is a cruel thing.

Today, the first indication that your teenage child is having a relationship is the increasing size of their mobile phone bill. The notion that teenage romance led to hours on the phone was somewhat alien in my youth: talking on the house phone at all was a rare event. The phone was for emergencies. Besides, the phone lived on a table positioned in the hallway under the stairs – the most public place in the house. Nowadays, people are suggesting that parents need to monitor their children’s activities on social networking sites to find out to whom they are talking. That wasn’t required in the eighties – if your mum wanted to know what you were up to, she just sat on the stairs.

Today, every individual in my house has their own mobile phone, and we have various telephone extensions around the house – to the extent that it is impossible not to be available for immediate communication. This has created a difficult situation for this generation of teenagers, as they have never known anything but instant communication. If the internet goes down in my house, it’s the end of the world, and the children immediately get in touch with social services to report neglect.

But the flip side to this is that if they leave the house and I want to know where they are going and what they are doing, I just ring them. (If you are a parent, you know that I’m lucky if they bother to answer the phone or tell me the truth, but allow me my fantasy.) Telecommunication has lost all its magic for them, which is sad in some ways. They will never know the excitement of a phone call after nine at night: anyone ringing our house that late was only doing it to say someone was dead, and it was always great family fun to guess who before the phone was picked up.

Often the quickest way to converse with teenagers today is via text, even if they are in the same room. I once had a text row with my son when we were sitting on the same couch! I lost, as every adult that tries to communicate with the ‘youth of today’ inevitably will do when the process of communication involves only using your thumbs. Watching my kids texting looks a blur to me: it’s like their two thumbs are having a race. Their head is bowed, and the concentration on the face and the general stillness could easily be interpreted as meditation, were it not for the frenetic thumb action. Having a text row with them is pointless because before you can finish your text to them they have replied, told you how wrong you are, how great everyone else’s parents are and how you are ruining their life.

This evolution of communication is the biggest difference between my kids and my own development as a teenager. For me, football provided a way to enter the adult world. During my teenage years my dad ran Sunday league teams. We would travel together as a squad, play the game, go to the pub afterwards and be home for the Sunday roast my mum had prepared. During those years I learnt how to be amongst men. I also learnt that if you make a commitment, you stick to it. So even on wet Sunday mornings, when your bed was calling you, you got up and went to play on whatever pitch you were sent to that week.

Trying to recall my teenage years, I can remember football constantly being there. The academy system that most clubs run these days did not exist then, so it was possible to believe you might become a professional footballer even if you hadn’t been scouted by the time you were 20. There were always examples of top-flight footballers who, a few years earlier, had been playing Sunday league football. The consequence was that amateur football was very vibrant: people still had dreams, and those dreams had a chance of being realised. It wasn’t difficult to get kids together either, because everyone wanted to play. In a world without computer games or, for that matter, home computers, and where children’s TV was only on for a few hours after school, if you didn’t go out and do something your options were very limited.

Having run kids’ teams myself in recent years, I don’t recall levels of parental involvement or interference being as high back then, either. I don’t recollect my dad having to drop us off and pick us up in the same way my wife and I have spent the last few years doing – to the point that if there is one luxury I have allowed myself, it is to set up a taxi account. My secret ambition is to one day own a car and sell it years later, without it ever having been used to ferry them anywhere. When my oldest son recently passed his driving test, my wife and I sat back and planned what we would do with all the spare time we would now gain from not driving him around. She is considering a second degree and I am planning to learn Chinese.

The truth was that we expected less then. Youth teams barely had full kits, let alone matching hoodies and personalised bags. The parents who did come generally did so to support the lads; there was no need for rope around the pitch to prevent irate parents coming onto the field to either support or bollock their little Johnny. The level of organisation in youth football now is impressive. Team coaches have to pass an approved FA coaching course, people involved are CRB checked, and my son’s under-15 team has to line up to have their photo ID-checked by the opposition manager before every game.

I think some of this can be overkill, like being CRB-checked to take your own son and his friends to a game, even though they all stayed at your house the night before. (This was actually suggested to me a few years ago – you can imagine my response.) It’s great to be organised, but you don’t want to take the simple pleasure out of the game. Although I do think the ID cards are a good idea, as it prevents teams playing ‘ringers’: I recall playing a game against one team when I was 15, which we lost. At the end of the game their bearded centre-half drove himself and his watching wife and kids home.

As a teenager the team I played for was Halton Sports. It was run by my dad’s friend, Joe Langton, whose son, Peter, also played. Joe was a barrel-chested man with a bald head, the crown of which was framed by short, blond hair. He always sported a neat moustache. A strong man whose day job was laying flag stones, Joe was almost square in shape. The joke amongst the lads was that he had once been six-foot-seven and a house had fallen on him to make him the square five-foot-six he actually was. Joe took it so seriously that he would often turn up in a three-piece suit, ready for an interview with Match of the Day should they turn up.

The team was good. The better players from our school team played, boys like Mark Donovan, Sean Johnson and Curtis Warren – not the infamous Liverpool gangster, but a fast, ginger-haired lad who scored a lot of goals. We were joined by good lads from the schools’ representative team, like John Hickey and Peter Golburn. I only list the names because none of us became professional footballers – which was an obvious ambition for us all – and every single one of those listed would have been good enough.

I would possibly suggest that playing in Joe’s team was the highest sporting success most of us enjoyed, as we spent one season completely unbeaten and won most things in the years that we played. My dad kept all the newspaper clippings of my resulting football career, and I always look at the coverage of that period with affection.

• • •

Apart from playing football, there was not a lot to do on the estate. When I was a bit older I volunteered at a cancer hospice, but in my early teens I never went to a youth club or anything of that nature, and generally just hung around on my bike doing all the things teenage boys do. I never really got into too much trouble. Scrapping had been replaced by an interest in girls, and the knowledge that as you all grew bigger it hurt more when you got hit. I never did the drinking-cider-on-a-wall-and-smoking thing that many started to do in their mid-teens because I had promised my dad I would never smoke, a promise he made all four of us make to him from a very early age, and which none of us has broken – apart from allowing myself the odd cigar. (That habit began one night in a posh hotel in Valletta, Malta. I found myself alone with an 80-year-old barman called Sonny, drinking a glass of whisky and listening to Frank Sinatra. Having a cigar seemed the most appropriate thing in the world.)

When I was 13 and feeling the need to be more independent and spread my wings outside the estate, football things were replaced by a bicycle. It was a silver ‘racer’, which basically meant it weighed a ton but had curved handlebars. Due to a cock-up by the catalogue company, I didn’t actually get the bike till Easter, so on Christmas Day my present was a box containing Cluedo. A great game, but not a great way to get around the estate. I hope I hid my disappointment well enough on the day when asking through gritted teeth – when my mates were all out on their new bikes – ‘Was it Professor Green with the lead piping?’

With the ability to stagger repayments, the catalogue was the avenue through which many people on the estate purchased things that were out of their reach financially. Every time a White Arrow van arrived on the estate, you knew someone was getting something from the catalogue. The bike was my final present as a child. Every year previously for Christmas I received something football-related. After the bike, all my Christmas presents were things to make me look good or allow me to go out; in other words, money or clothes. Unless it was a book voucher, which no kid wants as a Christmas present – you may as well give them an abacus and say, ‘Go and try to be a bit cleverer next year.’