По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

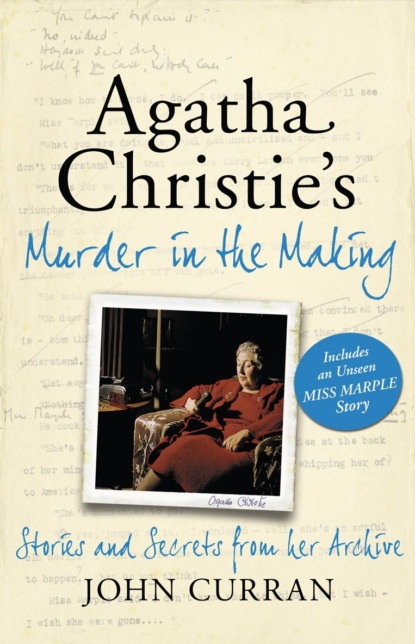

Agatha Christie’s Murder in the Making: Stories and Secrets from Her Archive - includes an unseen Miss Marple Story

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Knox 2. All supernatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

Van Dine 8. The problem of the crime must be solved by strictly naturalistic means.

These two Rules are, in effect, the same and are more strictly adhered to, but Christie still sails close to the wind on various occasions, especially in her short story output. The virtually unknown radio play Personal Call has a supernatural twist at the last minute just when the listener thinks that everything has been satisfactorily, and rationally, explained. Dumb Witness features the Tripp sisters, quasi-spiritualists, but apart from her collection The Hound of Death, which has a supernatural rather than a detective theme, most of Chritie’s stories are firmly rooted in the natural, albeit sometimes evil, real world. The Pale Horse makes much of black magic and murder-by-suggestion but, like ‘The Voice in the Dark’ from The Mysterious Mr Quin and its seeming ghostly presence, all is explained away in rational terms.

Van Dine 3. There must be no love interest.

Although Van Dine managed this in his own books (thereby reducing them to semi-animated Cluedo), this Rule has been ignored by most successful practitioners. It is in the highest degree unlikely that, in the course of a 250-page novel, the ‘love interest’ can be completely excised while some semblance of verisimilitude is retained. Admittedly, Van Dine may have been thinking of some of the excesses of the Romantic suspense school, when matters of the heart take precedence over matters of the intellect; or when the reader can safely spot the culprit by pairing off the suspects until only one remains. Christie, as usual, turned this rule to her advantage. In some novels we confidently expect certain characters to walk up the aisle after the book finishes but, instead, one or more of them end up walking to the scaffold. In Death in the Clouds, Jane Grey gets as big a shock as the reader when the charming Norman Gale is unmasked as a cold-blooded murderer. In Taken at the Flood, Lynn is left pining after the ruthless David Hunter and in They Came to Baghdad, Victoria is left to seek a replacement for the shy Edward. In some Christie novels the ‘love interest’ or, more accurately, the emotional element and personal interplay between the characters, is not just present but of a much higher standard than is usual in her works. For example, in Five Little Pigs, The Hollow and Nemesis it is the emotional entanglements that set the plot in motion and provide the motivation; in each case it is thwarted love that motivates the killer.

Van Dine 16. A detective novel should contain no long descriptive passages, no literary dallying with side-issues, no subtly worked-out character analyses, and no ‘atmospheric’ preoccupations.

This Rule merely mirrors the time in which it was written. And it must be admitted that it would be no bad matter to reintroduce it to some present-day practitioners. Many examples of current detective fiction are shamelessly overwritten and never seem to use ten words when a hundred will do. That said, character analysis and atmosphere can play an important part in the solution. In The Moving Finger, it is only when Miss Marple looks beyond the ‘atmosphere’ of fear in Lymstock that the solutions both to the explanation of the poison-pen letters and the identity of the murderer become clear. In Cards on the Table the only physical clues are the bridge scorecards and Poirot has to depend largely on the character of the bridge-players, as shown by these scorecards, to arrive at the truth. In Five Little Pigs, an investigation into the murder committed 16 years earlier has to rely almost solely on the evidence and accounts of the suspects. Character reading and analysis play an important part in this procedure. In The Hollow, it is from his study of the characters staying for the weekend at The Hollow that Poirot uncovers the truth of the crime. Apart from the gun there is nothing in the way of physical clues for him to analyse.

RULE OF THREE: SUMMARY

The Knox Decalogue is by far the more reasonable of the two sets of Rules. Written somewhat tongue-in-cheek – ‘Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable’ – it is less repetitive and restrictive and shows less personal prejudice than does its American counterpart. A strict adherence to Van Dine’s Rules would have resulted in an arid, uninspired and ultimately predictable genre. It would have meant for-going (much of) the daring brilliance of Christie, the inventive logic of Ellery Queen, the audacious ingenuity of John Dickson Carr or the formidable intelligence of Dorothy L. Sayers. In later years it would have precluded the witty cunning of Edmund Crispin, the erudite originality of Michael Innes or the boundary-pushing output of Julian Symons. Van Dine’s list is repetitive and, in many instances, a reflection of his personal bias – no long descriptive passages, no literary dallying with side-issues, no subtly worked-out character analyses, no ‘atmospheric’ preoccupations. It is somewhat ironic that while the compilers of both lists are largely forgotten nowadays, the writer who managed to break most of their carefully considered Rules remains the best-selling and most popular writer in history.

And so, from The Mysterious Affair at Styles in 1920 until Sleeping Murder in 1976, Agatha Christie produced at least one book a year and for nearly twenty of those years she produced two titles. The slogan ‘A Christie for Christmas’ was a fixture in Collins’s publishing list and in 1935 it became clear that the name of Agatha Christie was to be a perennial best seller. That year, with Three Act Tragedy, she reached the magic figure of 10,000 hardback copies sold in the first year. And this trebled over the next ten years. By the time of her fiftieth title, A Murder is Announced, she matched it with sales of 50,000; and never looked back. And all of this without the media circus that is now part and parcel of the book trade – no radio or TV interviews, no signing sessions, no question-and-answer panels and virtually no public appearances.

Although mutually advantageous, the relationship between Christie and her publisher was by no means without its rockier moments, usually about jacket design or blurb. The proposed design for The Labours of Hercules horrified her (‘Poirot going naked to the bath’), she considered that an announcement in ‘Crime Club News’ about 1939’s Ten Little Niggers – its title later amended to the more acceptable And Then There Were None – revealed too much of the plot (see Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks), and in September 1967 she sent Sir William (‘Billy’) Collins a blistering letter for not having received her so-called advance copies of Endless Night before she saw them herself on sale at the airport. And as late as 1968 she wrote her own blurb for By the Pricking of my Thumbs.

Thanks to her phenomenal sales and prodigious output, she became a personal friend of Sir William and his wife, Pierre, and conducted much of her correspondence through the years directly with him. They were regular visitors to Greenway, her Devon retreat, and Sir William was one of those who spoke at her memorial service in May 1976. A measure of the respect in which he held her can be gauged from his closing remarks, when he said that ‘the world is better because she lived in it’.

2

The First Decade 1920–1929

‘It was while I was working in the dispensary that I first conceived the idea of writing a detective story.’

SOLUTIONS REVEALED

The Mysterious Affair at Styles • The Mystery of the Blue Train

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published in the USA at the end of 1920 and in the UK on 21 January 1921. It is a classic country-house whodunit of the sort that would eventually become synonymous with the name of Agatha Christie. Ironically, over the following decade she wrote only one more ‘English’ domestic whodunit, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926). The other two whodunits of this decade are set abroad – The Murder on the Links (1923) is set in Deauville, France and The Mystery of the Blue Train (1928) has a similar South of France background. With the exception of the last title, which Christie, according to her Autobiography, ‘always hated’ and had ‘never been proud of’, they are first-class examples of the classic detective story then entering its Golden Age. Each title, with the same exception, displays the gifts that would later make Agatha Christie the Queen of Crime – uncomplicated language briskly telling a cleverly constructed story, easily recognisable and clearly delineated characters, inventive plots with all the necessary clues given to the reader, and an unexpected killer unmasked in the last chapter. These hallmarks would continue to be a feature of Christie’s books until the twilight of her career, half a century later.

The rest of her novels of the 1920s consist of thrillers, both domestic – The Secret Adversary (1922), The Secret of Chimneys (1925) and The Seven Dials Mystery (1929) – and international – The Man in the Brown Suit (1924). While none of these titles are first-rate Christie, they all exhibit some elements that would appear in later titles. The Secret Adversary, the first Tommy and Tuppence adventure, unmasks the least likely suspect while The Man in the Brown Suit is an early experiment with the famous Roger Ackroyd conjuring trick. The Seven Dials Mystery subverts reader expectation of the ‘secret society’ plot device and The Secret of Chimneys, a light-hearted mixture of missing jewels, international intrigue, incriminating letters, blackmail and murder in a high society setting, shows early experimentation with impersonation and false identity.

Throughout the 1920s Christie’s short story output was impressive. She published three such collections in the decade. The contents of Poirot Investigates (1924) first appeared in The Sketch, in a commissioned series of short stories, starting in March 1923 with ‘The Affair at the Victory Ball’. By the end of that year two dozen stories had appeared and 50 years later the remainder of these stories had their first UK book appearance in Poirot’s Early Cases. In 1953 Christie dedicated A Pocket Full of Rye to the editor of The Sketch, ‘Bruce Ingram, who liked and published my first short stories.’ In 1927, at a low point in Christie’s life, after the death of her mother and her own disappearance, The Big Four was published. This episodic Poirot novel, consisting of a series of connected short stories all of which had appeared in The Sketch during 1924, can also be considered a low point in the career of Hercule Poirot as he battles with a gang of international criminals intent on world domination. The last collection of the decade is the hugely entertaining Partners in Crime (1929). These Tommy and Tuppence adventures, most of which had appeared in The Sketch also during 1924, were pastiches of many of the crime writers of the time – ‘The Man in the Mist’ (G.K. Chesterton), ‘The Case of the Missing Lady’ (Conan Doyle), ‘The Crackler’ (Edgar Wallace) – and, while light-hearted in tone, contain many clever ideas.

Apart from her crime and detective stories, tales of the supernatural, romance and fantasy all appeared under her name in many of the multitude of magazines that filled the bookstalls. Many of the stories later published in the collections The Mysterious Mr Quin, The Hound of Death and The Listerdale Mystery were written and first published in the 1920s. And, of course, it was during the 1920s that Miss Marple made her first appearance, in the short story ‘The Tuesday Night Club’, published in The Royal Magazine in December 1927. With the exception of the final entry, ‘Death by Drowning’, the stories that appear in The Thirteen Problems were all written in the 1920s and appeared in two batches, the first six between December 1927 and May 1928, and the second between December 1929 and May 1930. In 1924 her first poetry collection The Road of Dreams was published. And it seems likely that her own stage adaptation of The Secret of Chimneys was begun in the late 1920s, as was the unpublished and unperformed script of the macabre short story ‘The Last Séance’.

The other important career decision taken in 1923 was to employ the services of a literary agent, Edmund Cork. The first task undertaken by Cork was to extricate Christie from a very one-sided contract with The Bodley Head Ltd and negotiate a more favourable arrangement with Collins, the publisher with which she was destined to remain for the rest of her life; as, indeed, she did with Edmund Cork.

Three of the best short stories Christie ever wrote were published during this decade. In January 1925 ‘Traitor Hands’, later to achieve immortality as the play, and subsequent film, Witness for the Prosecution, appeared in Flynn’s Weekly. The much-anthologised ‘Accident’ was published in the Daily Express in 1929; this was later adapted by other hands into the one-act play Tea for Three. And ‘Philomel Cottage’, which spawned five screen versions as Love from a Stranger, appeared in The Grand in November 1924.

Finally, the first stage and screen version of her work appeared during the 1920s. Alibi, adapted for the stage by Michael Morton from The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, opened in May 1928 while the same year saw the opening of films of The Secret Adversary – as Die Abenteuer G.m.b.h. – and The Passing of Mr Quinn, based loosely on the short story ‘The Coming of Mr Quin’.

This hugely prolific decade shows Christie gaining an international reputation while experimenting with form and structure within, and outside, the detective genre. Although her first novel was very definitely a detective story, her output for the following nine years returned only three times to the form in which she was eventually to gain immortality.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

21 January 1921

Arthur Hastings goes to Styles Court, the home of his friend John Cavendish, to recuperate during the First World War. He senses tension in the household and this is confirmed when his hostess, John’s stepmother, is poisoned. Luckily, a Belgian refugee staying nearby is an old friend, a retired policeman called Hercule Poirot.

In her Autobiography Agatha Christie gives a detailed account of the genesis of The Mysterious Affair at Styles. By now, the main facts are well known: the immortal challenge – ‘I bet you can’t write a good detective story’ – from her sister Madge, the Belgian refugees from the First World War in Torquay who inspired Poirot’s nationality, Christie’s knowledge of poisons from her work in the local dispensary, her intermittent work on the book and its eventual completion, at the encouragement of her mother, during a two-week seclusion in the Moorland Hotel. This was not her first literary effort, nor was she the first member of her family with literary aspirations. Both her mother and sister Madge wrote, and Madge actually had a play, The Claimant, produced in the West End before Agatha did. Agatha had already written a ‘long dreary novel’ (her own words in a 1955 radio broadcast) and some short stories and sketches. While the story of the bet is realistic, it is clear that this alone would not be stimulus enough to plot, sketch and write a successful book. There was obviously an innate gift and a facility with the written word.

Although she began writing the novel in 1916 (The Mysterious Affair at Styles is actually set in 1917), it was not published for another four years. And its publication was to demand consistent determination on its author’s part as more than one publisher declined the manuscript. Eventually, in 1919, John Lane, co-founder of The Bodley Head Ltd, asked to meet her with a view to publication. But, even then, the struggle was far from over.

The contract, dated 1 January 1920, that John Lane offered her took advantage of Agatha Christie’s publishing naivety. She explains in her Autobiography that she was ‘in no frame of mind to study agreements or even think about them’. Her delight at the prospect of publication, combined with the conviction that she was not going to pursue a writing career, persuaded her to sign. Remarkably, the actual contract is for The Mysterious Affair of (rather than ‘at’) Styles. She was to get 10 per cent only after 2,000 copies were sold in the UK and she was contracted to produce five more titles. This clause was to lead to much correspondence over the following years.

Later, as her productivity, success and popularity increased and she realised what she had signed, she insisted that if she offered a book she was fulfilling her side of the contract whether or not The Bodley Head accepted it. When they expressed doubt as to whether Poirot Investigates, as a volume of short stories rather than a novel, should be considered part of the six-book contract, the by now confident writer pointed out that she had offered them the non-crime Vision, described in Janet Morgan’s Agatha Christie: A Biography as a ‘fantasy’, as her third title. The fact that her publisher had refused it was, as far as she was concerned, their choice. It is quite possible that if John Lane had not tried to take advantage of his literary discovery she might have stayed longer with The Bodley Head. But the prickly surviving correspondence shows that those early years of her career were a sharp learning curve in the ways of publishers – and that Agatha Christie was a star pupil. Within a relatively short space of time she is transformed from an awed and inexperienced neophyte perched nervously on the edge of a chair in John Lane’s office to a confident and business-like professional with a resolute interest in every aspect of her books – jacket design, marketing, royalties, serialisation, translation and cinema rights.

The readers’ reports on the Styles manuscript were, despite some misgivings, promising. One gets right to the commercial considerations: ‘Despite its manifest shortcomings, Lane could very likely sell the novel …. There is a certain freshness about it.’ A second report is more enthusiastic: ‘It is altogether rather well told and well written.’ And another speculates on her potential future ‘if she goes on writing detective stories and she evidently has quite a talent for them’. The readers were much taken with the character of Poirot – ‘the exuberant personality of M. Poirot who is a very welcome variation on the “detective” of romance’; ‘a jolly little man in the person of has-been famous Belgian detective’. Although Poirot might take issue with the use of the description ‘has-been’, it was clear that his presence was a factor in the manuscript’s acceptance. In a report dated 7 October 1919 one very perceptive reader remarked, ‘but the account of the trial of John Cavendish makes me suspect the hand of a woman’. Because her name on the manuscript appears as A.M. Christie, another reader refers to ‘Mr. Christie’.

Despite these favourable readers’ reports, there were further delays and after a serialisation in The Weekly Times – the first time a ‘first’ novel had been chosen – beginning in February 1920, Christie wrote to Mr Willett at The Bodley Head in October that year wondering if her book was ‘ever coming out’ and pointing out that she had almost finished her second one. This resulted in her receiving the projected cover design, which she approved. Eventually, The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published later that year in the USA. And, almost five years after she began it, Agatha Christie’s first book went on sale in the UK on 21 January 1921. Even after its appearance there was much correspondence about statements and incorrect calculations of royalties as well as cover designs. In fairness to John Lane and The Bodley Head, cover design and blurbs also featured regularly throughout her career in her correspondence with Collins.

As we have seen, one of the readers’ reports mentioned the John Cavendish trial. In the original manuscript, Poirot’s explanation of the crime is given in the form of his evidence in the witness box during the trial. In her Autobiography Christie describes John Lane’s verdict on her manuscript, including his opinion that this courtroom scene did not convince and his request that she amend it. She agreed to a rewrite and although the explanation of the crime itself remains the same, instead of giving it in the course of the judicial process, Poirot holds forth in the drawing room of Styles in the kind of scene that was to be replicated in many later books.

Incredibly, almost a century later – it was written, in all probability, in 1916 – the deleted scene has survived in the pages of Notebook 37, which also contains two brief and somewhat enigmatic notes about the novel. Equally incredible is the illegibility of the handwriting. It was written in pencil, with much crossing out and many insertions. This is difficult enough, but an added complication lies in the fact that Christie often replaced the deleted words with alternatives, squeezed in, sometimes at an angle, above the original. And although the explanation of the crime is, in essence, the same as the published version, the published text was of limited help. The wording is often different and some names have changed. Of the Notebooks, this exercise in transcription was the most challenging of all. The fact that it is Agatha Christie’s and Hercule Poirot’s first case made the extra effort worthwhile.

In the version that follows I have amended the usual Christie punctuation of dashes to full stops and commas, and I have added quotation marks throughout. I use square brackets where an obvious, or necessary, word is missing in the original; a few illegible words have been omitted. Footnotes have been used to draw attention to points of particular interest.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

The story so far …

When wealthy Emily Inglethorp, owner of Styles Court, remarries, her new husband Alfred is viewed by her stepsons, John and Lawrence, and her faithful retainer, Evelyn Howard, as a fortune-hunter. John’s wife, Mary, is perceived as being over-friendly with the enigmatic Dr Bauerstein, a German and an expert on poisons. Also staying at Styles Court, while working in the dispensary of the local hospital, is Emily’s protégée Cynthia Murdoch. Then Evelyn walks out after a bitter row. On the night of 17 July Emily dies from strychnine poisoning while her family watches helplessly. Hercule Poirot, called in by his friend Arthur Hastings, agrees to investigate and pays close attention to Emily’s bedroom. And then John Cavendish is arrested …

Poirot returned late that night.

I did not see him until the following morning. He was beaming and greeted me with the utmost affection.

‘Ah, my friend – all is well – all will now march.’

Notebook 37 showing the beginning of the deleted chapter from The Mysterious Affair at Styles.

‘Why,’ I exclaimed, ‘You don’t mean to say you have got—’

‘Yes, Hastings, yes – I have found the missing link.

Hush …’

On Monday the hearing was resumed

and Sir E.H.W. [Ernest Heavywether] opened the case for the defence. Never, he said, in the course of his experience had a murder charge rested on slighter evidence. Let them take the evidence against John Cavendish and sift it impartially.

What was the main thing against him? That the powdered strychnine had been found in his drawer. But that drawer was an unlocked one and he submitted that there was no evidence to show that it was the prisoner who placed it there. It was, in fact, a wicked and malicious effort on the part of some other person to bring the crime home to the prisoner. He went on to state that the Prosecution had been unable to prove to any degree that it was the prisoner who had ordered the beard from Messrs Parksons. As for the quarrel with his mother and his financial constraints – both had been most grossly exaggerated.