По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

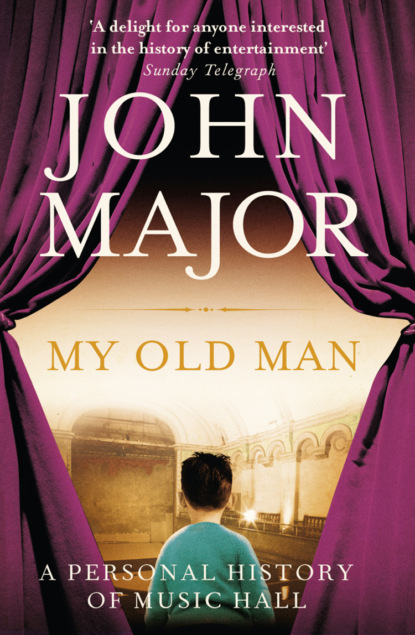

My Old Man: A Personal History of Music Hall

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Sadler promoted the waters as able to cure ‘dropsy, jaundice, scurvy, green sickness and other distempers to which females are liable [he knew his clientèle] – ulcers, fits of the mother, virgin’s fever and hydrochondriacal distemper’. He obtained endorsements from ‘eminent’ physicians, and hundreds of fashionable Londoners were sufficiently convinced to become patrons. Sadler added pipe, tabor and dulcimer musicians to sweeten the experience. ‘Sadler’s Wells’ was soon staging operas.

As competition grew with the discovery of more wells, the genteel air gave way to less refined customers demanding a more earthy experience. Sadler provided it. The operas were replaced by such tasteless absurdities as ‘the Hibernian Cannibal’, who devoured a live cockerel, ‘feather, feet and all’, washed down with a pint of brandy.

William Wordsworth recorded seeing ‘giants and dwarfs, clowns, conjurers, posture makers, harlequins/Amid the uproar of the rabblement, Perform their feats’. A noisy audience and a variety of acts was not yet music hall, but entertainment was being propelled in that direction. Managers were prepared to stage anything to find and hold an audience.

One of the ruses at Sadler’s Wells was to brew very strong beer, and advertise it:

Haste hither, then, and take your fill,

Let parsons say whate’er they will,

The ale that every ale excels

Is only found at Sadler’s Wells.

Sadler’s Wells is relevant to the story of music hall because it shows how landlords, proprietors and managers relentlessly followed the market to maximise profitability. It was their job to give the public what it wanted and to ‘talk it all up’. It was exactly this approach that would drive the development of music hall.

Other early influences on music hall were catch and glee songs. ‘Catches’ – so-called because they were catchy – were songs with simple harmonies composed almost exclusively for male voices. They were initially humorous and light-hearted in content, and intended for the convivial atmosphere of clubs and taverns. As they became identified with low humour and bawdy lyrics, their fan base widened and they became a staple of late-night entertainment.

The first collection of catches was published by Thomas Ravenscroft in 1609. Yet we know they existed by 1600. In Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night (c.1601) Sir Toby Belch and Sir Andrew Aguecheek are rebuked by Malvolio, never one for mirth, for singing catches with Feste the clown: ‘My masters, are you mad? Have you no wit … but to gabble like tinkers? Do ye make an alehouse of my Lady’s house, that ye squeak out your coziers’ [tailors’] catches?’ It is a revealing accusation, telling us that catches were considered plebeian, but were enjoyed by gentlemen as well as tradesmen. They were convivial and drink-related, probably very rude, and were disapproved of by the Puritan-minded.

Ironically, Puritan hostility may have actively promoted catch-singing. When the Puritan Parliament of 1642 passed legislation to close the theatres, it inadvertently moved the displaced musicians and singers to taverns and inns, where catch-singing took hold. Even worse, many of the organs the Puritans removed from churches also found their way into taverns. In 1657 Parliament responded by passing an ordinance banning ‘idle, dissolute persons commonly called fiddlers and minstrels … from making musick in any Inn, Tavern or Alehouse’. Singing was also banned, but enterprising tavern-owners either turned a blind eye to the law or deliberately misinterpreted it. A mere two years later, the Black Horse tavern in Aldersgate Street was operating as a ‘Musick House’ featuring catches.

The following year, the Puritan Commonwealth was gone and Charles II was on the throne. Music houses began to proliferate, and to move upmarket, as is shown by Samuel Pepys dedicating a book of catch lyrics to his friends at ‘the late Musick Society and Meeting at the Old Jury, London’. Pepys and other contemporary commentators describe a tavern-based scene of music, ale or wine, enjoyed convivially, served by a landlord-in-attendance to a socially diverse group of singers. Henry Purcell was responsible for providing the music to some of the ripest lyrics, perhaps as light relief among the operas, anthems, Court odes and other works of this great British composer.

The most famous of the ‘catch clubs’ was founded by the 4th Earl of Sandwich at the Thatched House tavern in 1762, on a site that is now at the lower end of London’s St James’s Street. The Noblemen’s and Gentlemen’s Catch Club was a highly exclusive dining and drinking club for the cream of Georgian society, where dukes and earls mingled with generals and admirals. Its secretary, Edmund Warren, published collections of catches and left an exhaustive record of the club. The membership clearly shared a love of wine as well as music: in June 1771, 798 quart bottles of claret alone were purchased for only twenty-six members. Non-alcoholic drinks were frowned on, and members who requested them were asked, presumably tongue-in-cheek, to drink ‘at a distant table’, and to do so with ‘a due sense of the society’s indulgence’. Fines were levied for absence or lateness, and ‘drinking fines’ for talking about politics or religion – or singing out of tune. A donation to the club, in the guise of a fine, was expected from any member benefiting from a large inheritance. But the club was more than a bolt-hole for society drunkards. It supported the contemporary music scene, awarding medals and prizes to young performers, while professional musicians such as the popular tenor John Beard and the composer Thomas Arne were among the honorary members.

The club medals bore the motto ‘Let’s drink and sing together’, and they ate together too. The landlord of the Thatched House, William Almack,* (#ulink_6b7680a8-408a-5042-9d7f-9be576cee832) served dinner at 4 p.m., and kept refreshment coming for the next nine hours. After dinner and Grace were concluded, fines were announced, the singing began and the drink flowed .

By 1800, catch-singing was a feature of autumn and winter evenings in taverns across the country. Such evenings took a form that would set a pattern for music hall. A chairman was appointed – usually the publican – who would preside over the entertainment, introduce guest singers and direct the club’s affairs: he did, after all, have a pecuniary interest in its success. The evenings would grow increasingly raucous as the drinking proceeded, and thus the chairman would give events a continued focus. Membership was by subscription, and catch clubs attracted a wide social mix, from aristocrats to the working class, although the more staid middle classes were rarely there. As the evening wore on, the songs became more ribald, and vulgar and obscene lyrics were performed to enthusiastic applause.

The sheer vulgarity of catches helped encourage the popularity of glees. Musicians began to shy away from the crude nature of catches, preferring the more musically sophisticated glees. Glees were also more sentimental, and had wider appeal to both men and women. When a glee club was established at the Newcastle Coffee House in 1787, its founders were largely professional members of the existing catch club who were serious about their music and shied away from the bawdiness of taverns. Coffee houses became their favoured meeting places.

Thomas Lowe presented both catch and glee concerts at Ranelagh Gardens in 1765 in an attempt to boost its flagging fortunes. This, at least, was a success, and catch and glee songs – the catch lyrics being suitably sanitised for the mixed audiences – became a staple ingredient of the pleasure gardens’ programme by the end of the eighteenth century. Drury Lane copied Lowe’s initiative, followed by the Haymarket Theatre in 1770. Until well into the nineteenth century, catches and glees featured on the bill of any theatre or pleasure garden that wished to attract a popular crowd.

By the early nineteenth century, glees – with their sentimentality, inoffensive lyrics and more complex music – began to outstrip the popularity of catches, and the two genres went their separate ways. Catches – with their bawdy, single-sex conviviality and association with bibulous revelry – were to find a new home, and a wider audience, in song and supper clubs. As these began to attract the patronage of the well-heeled bohemian man-about-town, the taverns lost their social mix and became more of a working-class preserve. Glees went on to lay the basis for the songs that would delight audiences throughout and well beyond the era of music hall. Catch and glee singing, and their tavern roots, laid the foundations for the informal, accessible, and initially amateur, but later professional-led, sing-songs that were an important staging post to music hall.

* (#ulink_2f862602-d1a3-52ec-b46a-16e635634873) The rewards of hosting the catch club were significant – Almack became extremely wealthy; among his enterprises was a gambling club in Pall Mall which subsequently became Brooks’s Club.

2

The Basement and the Cellars (#u7d2b65db-34ec-5f6b-b39e-e51127a2107f)

‘A guinea a week and supper each night.’

TERMS OF EMPLOYMENT AT THE CYDER CELLARS

Song and supper rooms, true to their name, were late-night venues offering hot food and musical entertainment. Together with their imitators they were the direct predecessors of music hall. The three most famous were Evans’ Late Joy’s in King Street, Covent Garden, the Coal Hole in Fountain Court, The Strand, and the Cyder Cellars in Maiden Lane. All three catered for bohemian and well-heeled London society. But elsewhere, in London and beyond, variety saloons and concert halls attached to taverns offered similar fare and fun at lower cost, while pubs accommodated the working man in ‘free and easies’. Evans’ Late Joy’s was the pioneer: it initiated an interplay between performer and audience that would become an essential component of music hall.

Evans’ was situated on King Street, in the north-west corner of Covent Garden. The splendid red-bricked building, formerly the London residence of the Earl of Orford, was converted into the Grand Hotel in 1773, probably the first family hotel in London. Around the turn of the nineteenth century it became Joy’s Hotel, and as a dinner and coffee room it thrived on the patronage of the noble and the notable. Nine dukes were said to have dined there on one single evening, and the social elite flocked to the huge basement dining room.

But fashions change. Towards 1820 London society began its exodus further west, and the hotel clientèle faded away. The upper rooms were converted into residential apartments, and the basement was taken over by a former singer/comedian at the Covent Garden Theatre, W.C. Evans. Evans, a bluff, ruddy-faced John Bull of a figure, was moving up in the world, and was eager to display his elevation by renaming his new acquisition to reflect his ownership; but as a shrewd businessman, he wished also to exploit the favourable reputation Joy’s had earned. The uneasy compromise of the rather clumsily named Evans’ Late Joy’s was to launch a thousand smutty jokes.

Evans recast the great dining room into a song and supper room for gentlemen. Evans’ Late Joy’s opened at eight o’clock in the evening, began to fill up at ten, and was packed by midnight. It offered excellent but costly fare, which restricted its clientèle to the affluent. Night after night the hall was packed, the long tables hazy with cigar smoke and merry with good fellowship and noisy conversation. Boys from the Savoy Chapel sang unaccompanied glees. Madrigals were also popular, and choral singing and excerpts from opera enlivened many a night. In the jovial atmosphere, diners would offer their own songs or verses.

Soon professional acts were engaged – all male, naturally – to offer higher-quality entertainment. It must have been a tough assignment, for the food, drink and conviviality of the supper rooms were more important than the cabaret. Artistes had to perform over a perpetual din, and needed skill and personality to win over their audience. Some set a bawdy tone, and as the wine flowed and inhibitions fled, customers would join in to perform the rudest song or story in their repertoire. Evans himself would contribute with a song that became his signature: ‘If I Had a £1,000 a Year’, a sentiment that inspired many a bawdy response as the bills were settled.

Early performers at Evans’ included tenor John Binge, the comedians Jack Sharpe and Tom Hudson, Charles Sloman the Jewish singer/comedian, Joe Wells, and John Caulfield, Harry Boleno and Richard Flexmore, who went on to become the principal clowns at Drury Lane and Covent Garden.

Some of these performers did not live to see music hall thrive: Hudson, the son of a civil servant but himself apprenticed to a grocer, was a popular songwriter, mimic and singer who nevertheless died in poverty in 1844. He wrote and published songs about commonplace events of life that were familiar to his audience. One historian noted that, in Hudson, the lower middle class became articulate. His forte was comedy, and a line from one of his songs, about a sailor who returns to find his wife married to another, gave further currency to the enduring phrase ‘before you could say Jack Robinson’. After his death, friends arranged a benefit concert to raise funds for his widow and children, and subscriptions were offered by many notables, including the Lord Mayor, the Duke of Cambridge and Members of Parliament, as well as his fellow performers. It was a touching tribute to an engaging talent.

Charles Sloman was fiercely proud of the history of his race, which he commemorated in words and music. His career began in the pleasure gardens, but he soon graduated to the supper clubs. Sloman wrote many ballads – his most famous, ‘The Maid of Judah’, at the age of twenty-two – but his true gift was to ‘keep the table in a roar’ by conjuring a rhyme in song upon any subject shouted out to him by a well-refreshed diner. Often he mimicked the idiosyncrasies of diners or sang verses that teased or complimented them, much to the amusement of their companions. Throughout the 1830s Sloman was furiously busy as an entertainer, briefly (and unsuccessfully) as a theatre manager, and as chairman of festivities in taverns. After the 1840s his attraction declined and he was engaged in ever more downmarket venues. He died alone in the Strand workhouse in 1870.

Not everyone was a casualty of fleeting fame. Sam Collins was a firm favourite at Evans’ in the late period, put his money to good use, and at the age of thirty was part-owner of the Rose of Normandy Concert Room in Church Street, Marylebone. Later he bought the Lansdowne tavern and developed his own music hall – Collins’ Music Hall – before a premature death in his late thirties.

Others, less talented than Hudson, Sloman or Collins, were also successful in providing for themselves. After finishing his act – yodelling, imitations of birdsong and presenting his walking stick as a bassoon, flute, piccolo, trombone or violin, complete with sound effects – Herr von Joel, that refugee from Vauxhall Gardens, mingled among the audience selling cigars and tickets for his benefit concert. The cigars were poor value and the benefit a fiction, but no one cared. Cunning old von Joel was such an institution that – in an age in which fraud remained a capital crime – no one begrudged being swindled out of a few pennies.

Evans’ became more raucous as a song and supper room after 1844, when Evans retired and his successor, John Greenmore, known as Paddy Green, built up its reputation. Green had been the musical director during Evans’ reign, and like his old employer he was a former singer at Covent Garden Opera House. In the early 1850s he reconstructed the hall, and spent lavish sums on enlarging the dining room. He decorated the new ceiling, lit the room with sunlight burners and adorned the walls with portraits of theatrical personalities. A platform was erected to serve as a stage for the performers, and the old supper room was downgraded to a café lounge. The improved quality of the service, supplemented by fine food and drink, encouraged the air of masculine bonhomie. Teams of waiters and boys in buttoned waistcoats were on hand to take orders. Chops, kidneys and poached eggs were typical of the fare on offer, washed down with gin, whisky, hot brandy and water or stout. Bills – with the exception of cigars, which were paid for on demand – were settled on departure, with customers declaring what they’d consumed and a waiter called Skinner, known as ‘the calculating waiter’, totting up what was owed. This may have been a haphazard system, but it was an astute piece of marketing by Green. By not challenging what diners claimed had been consumed, he made it unseemly for them to question the waiter’s calculation. No doubt any errors of underdeclaration and overcharging balanced themselves out.

In the swirling smoke of cigars, and amid the clink of glasses and the clatter of cutlery, Paddy Green circulated with a kindly word for the literary, sporting, commercial, political and noble diners who assembled nightly at Joy’s. Posterity has been left a picture of a jovial, grey-haired elderly man moving through the room and beaming at his ‘dear boys’, his invariable greeting to clients, many of whose names he probably could not remember, while taking snuff and exuding an air of familiarity to all.

Green’s jolly nature did not, however, always extend to the most famous of his performers, Sam Cowell. Although tolerated by his admiring audience, Cowell’s habitual lateness exasperated Green. In his performances Cowell brought all his talents to bear: a gift for character, mimicry and visual expressiveness, and a strong, clear voice that enabled him to imbue narrative ballads with drama, comedy or pathos. His songs, often of thwarted love, became enormously popular. ‘Villikins’ and ‘The Ratcatcher’s Daughter’, performed in character with battered hat, seedy frock-coat and huge bow cravat, were demanded by audiences at every appearance. ‘The Ratcatcher’s Daughter’ tells the tale of two working-class sweethearts preparing to marry, although the would-be bride fears she will die before her wedding. And so she does, drowning in the Thames. Her broken-hearted lover then kills himself. We cannot be certain exactly how Sam Cowell presented this song, but its theme of love and tragedy touched the sentimental soul of Victorian London, and it’s easy to see why:

In Vestminster, not long ago,

There liv’d a ratcatcher’s daughter.

That is not quite in Vestminster,

’Cos she liv’d t’other side of the vater.

Her father killed rats and she cried Sprats

All around about that quarter.

The young gentlemen all touched their hats

To the purty little ratcatcher’s daughter.

Such a song could not fail. Though it (just) preceded the birth of the halls themselves, it is one of the first great music hall songs. Cowell sang it in a faux-cockney accent with, Sam Weller style, an inability to pronounce his W’s. It was a model for the rich vein of cockney humour that would follow.

Despite Cowell’s spectacular success, Paddy Green became so frustrated by his erratic timekeeping that he sacked his star performer for persistent lateness. Cowell never appeared at Evans’ again, but found ample employment elsewhere, most famously in the first purpose-built music hall, the Canterbury in Westminster Bridge Road, Lambeth.

Even without Cowell, Evans’ prospered. The principal comedian, Jackie Sharp, a specialist in unscripted, mildly risqué repartee, was at the top of his craft. Sharp’s act featured topical songs that satirised the government. The most well-known, ‘Who’ll Buy My Images?’ and ‘Pity Poor Punch and Judy’, were written by his friend and fellow performer John Labern, one of the foremost comic songwriters of the time. Sharp sang also of the evils of ‘the bottle’ at a time when overindulgence was a national pastime. Sadly, he himself did not heed the lyrics, and like so many others, he frittered away his fortune on alcohol and tobacco. At first drunkenness made him unreliable, and then unemployable. It was not long before a combination of exposure and malnutrition carried him off. He died in Dover Workhouse in 1856, at only thirty-eight years of age.

Cowell and Sharp were star attractions at Joy’s, but they were not alone: on any evening, another fifteen to twenty acts – the small, sweet-voiced tenor John Binge, known as ‘The Singing Mouse’; the big-voiced bass S.A. Jones; the ballad singer Joseph Plumpton – would be there to support them. Most performers were poorly paid, and would try to maximise their income by appearing at more than one venue on the same evening.

Sometime in the 1820s, William Rhodes, yet another former singer from the Covent Garden Theatre, acquired Evans’ principal rivals, the Coal Hole and the Cyder Cellars – the latter of which had hosted entertainment as early as the 1690s. Maiden Lane, where the Cyder Cellars was situated, had a famous pedigree. Voltaire and Henry Fielding had lived there, the great artist J.M.W. Turner was born there (to a wig-maker and his unstable wife), and Nell Gwynne was a resident towards the end of her life. Although the Cyder Cellars often employed the same artists as Evans’, it was far less reputable. It reached the peak of its notoriety around 1840, before Paddy Green took over Evans’, and remained a formidable competitor until its licence was revoked twenty-two years later.