По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

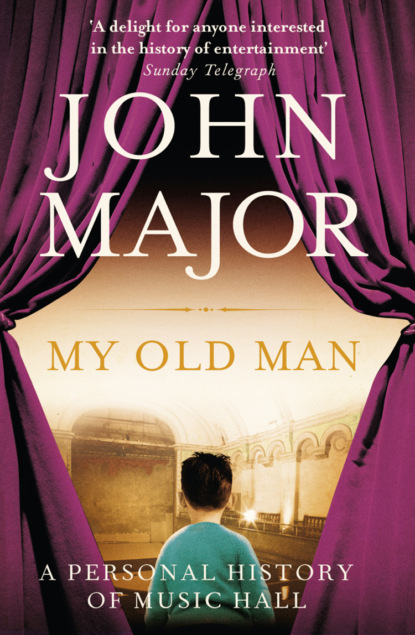

My Old Man: A Personal History of Music Hall

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Morton was a natural entrepreneur who understood the power of promotion. Bookmaking was a profitable sideline, and he promoted his sweepstakes for big race meetings by advertising in the Era.

Morton worked long hours to earn a more comfortable way of life. He was a very visible host, but, unusually for the time, he was abstemious, having no wish to drink away his profits. He walked and fished for recreation, making plans as he did so. As business prospered he traded up to the Crown in Pentonville, and then to the far more fashionable India House tavern in Leadenhall Street in the City. His credo was to exceed the expectations of his customers. At the India House he abandoned entertainment to concentrate on offering good fare in a congenial atmosphere – ‘Only one quality – the best’ had become his motto, and would remain so throughout his long life. The absence of entertainment defied convention, but in the City, where men met to eat and drink and discuss business, the India House was a haven – and a shrewd business move.

Despite the lack of song and dance at his City tavern, Morton never lost sight of the profit to be gained by feeding mind and body at the same time. He was a regular visitor to every sort of entertainment venue, and made note of money-making opportunities that were missed. He saw that the shows catered only for men: there were no women, no girls with their boyfriends, no families. Half the population was being ignored. Morton saw a huge untapped potential, and pondered how to exploit it without losing male patronage.

The solution was not obvious. Women had little or no money of their own, and even if they had, the social conservatism of the age would prevent them from attending taverns without a male escort. Morton realised that if men were accompanied by their wives or girlfriends, they would spend only the same sum between two customers. There was no extra profit in that. Worse, there might be a loss, since the entertainment mix would need to take account of females in the audience. The dilemma was still unresolved when Morton and his brother-in-law Frederick Stanley bought the Old Canterbury Arms in Westminster Bridge Road (then called Lambeth Marsh) in 1849. It was an ancient alehouse, once owned by the Canon of Rochester, and named as a homage to the medieval pilgrims who fed and watered there en route to the shrine of St Thomas à Becket.

The Canterbury Arms was in a squalid neighbourhood, but it had a theatrical pedigree stretching back three hundred years. It had been a favoured haunt of the Elizabethan actors of Bankside: Burbage, Henslowe, Jonson and Shakespeare were all said to have supped there. At the time of Morton’s purchase it had a regular clientèle who flocked there both to hear amateur talent in the modest music room, and to enjoy the four skittle alleys at the back.

Morton took over the Canterbury Arms’ licence in February 1850, but little was heard of him in the press for over two years, apart from a brief burst of publicity when a notorious skittle sharp, Joseph Jones, attracted police attention for his activities there. Morton’s uncharacteristic reticence ended as soon as his new hall was complete. In the Era of 16 May 1852 he promoted his new venture by funding a competition to determine the ‘champion swimmer of England’ between George Pewters and Frederick Beckwith. ‘Money ready’ for the winner, it said, at ‘Mr Morton’s Canterbury Arms, Lambeth’. In the news section of the same edition there is an entry: ‘The Canterbury Arms. A new and elegantly fitted up hall … and rumour speaks highly of all the arrangements.’ These news snippets suggest that Morton had delayed promoting his venture until he was completely satisfied with all the preparations. Now his vision was in place, and a notice the following week informed readers that ‘The Canterbury Music Hall offers superior talent … every attention paid to comfort and amusement … suppers, chops, steaks, etc etc. Admission by refreshment ticket, sixpence each person.’

The music room was adapted to a club room, where ‘free and easy’ concerts were held on Thursdays and Saturdays. With his usual attention to detail Morton set about providing excellent value in food and drink, but he was careful not to make changes that alienated the existing customers. More comfortable furniture and better lighting were introduced, and the walls were decorated with paintings and prints. There were roaring fires in the hearths, and spills to light pipes, cigars, and later the cigarettes popularised by soldiers returning from the Crimean War. Morton’s Canterbury was a warm and congenial environment, far more appealing than the cold, damp, cramped back-to-back houses that were home to so many of his customers. So they came and they stayed and they spent. As his profits grew Morton commissioned a new hall, to be built over the ramshackle skittle alleys.

He also hit upon an idea to attract women to the Canterbury without losing his existing customers. Rather than facing down social convention, Morton decided to bypass it. The admission fee of sixpence, which included drinks, was his answer to the conundrum of how to profit from women patrons. Since women rarely drank their full entitlement this proved a lucrative form of entry, and he actively encouraged them to attend his hall. A ‘Ladies Night’ was introduced in the club room once a week, which was a triumph. Morton’s brother Robert, a charmer with an excellent tenor voice, compèred evenings of entertainment that were packed to capacity. The mothers, daughters, wives, sisters, fiancées and girlfriends thoroughly enjoyed it, and their menfolk asked for the ladies to be admitted on other nights as well. Morton acquiesced, the objectors were outfoxed, and no one was offended.

Soon performances were staged every night, not just twice weekly. The Canterbury was no longer a pub, but a music hall. The package was complete: payment for entrance, refreshments available, entertainment based around comic ballads but with a wide variety of acts supporting them – and joyous, often uproarious participation from an audience of both sexes. The evening’s entertainment began at 7 p.m. and ended at midnight. And the money rolled in.

The Canterbury’s success was instant and overwhelming. Night after night seven hundred seats were sold and disappointed customers were turned away. Morton lined the walls with ‘lists’ of horses and race meetings so that customers could place bets while enjoying the show. ‘Lists’ were very popular, and the affinity between the turf and music hall remained strong until an Act of 1853 outlawed them.

Morton was a micro-manager who supervised everything. He booked the acts and was present at every performance. He formed his own resident choir, some members of which, including Haydn Corri, Edward Connell, St Clair Jones and Mrs John Caulfield, went on to enjoy successful solo careers in music hall. Nothing escaped his eye, and nothing was left to chance. He supervised the mobile ovens that baked potatoes, sometimes serving them to customers himself, with lashings of butter and seasoned with salt and pepper. Morton had an eye for detail, and nothing was overlooked.

The performers at the Canterbury were paid well – far more than the few shillings and free beer that were typical elsewhere – and under Morton’s patronage they became stars. His most glittering performer was Sam Cowell, he of ‘Villikins’ and ‘The Ratcatcher’s Daughter’ fame, who had been sacked from Evans’ by Paddy Green. Much Sam cared: he knew his value, and found a better berth with Morton, who paid him lavishly – up to £80 a week at his peak – and let him draw in the crowds.

Cowell’s story does not end happily. A man of weak constitution, he wasted too much of the money he earned on drink. In 1859 he returned from a gruelling twenty-month tour of America a very sick man. Long-distance travelling had left him poorly nourished, and temptation and free drinks had made him an alcoholic. His money was almost all gone. At Blandford, near Poole, he fell so ill that his wife was summoned from London, and he died in 1864, at only forty-four years of age, leaving his family nearly destitute. It was a sad ending for a man who ranks among the greatest of all music hall artistes.

Cowell was not the only refugee from the supper clubs. The old cigar con man Herr von Joel appeared, as did the mimic Charles Sloman, and song-and-supper-club regulars such as Robert Glindon and the wonderfully funny Jack Sharp. The comic singer Tom Penniket, an embryonic Dan Leno, was a frequent performer, and the tenor John Caulfield became the compère and chairman, with his son Johnny as the resident harmonium player. Many other popular artistes, such as the comedians Elija Taylor and Billy Pells, also delighted the Canterbury’s audiences. The basso-profundo St Clair Jones was in and out of favour with Morton for sloppy timekeeping, much as Sam Cowell had been at Evans’. Eventually Morton dismissed him, but the wily Jones then reappeared onstage to sing ‘I Cannot Leave Thee Yet’. The audience was won over – as was Morton – and Jones was reinstated.

Morton surveyed his full houses and his growing bank balance, and decided to expand. He had room to do so on his current site, but he had no wish to dismantle his theatre, lose a year’s revenue, and risk his regular audience developing other loyalties. He overcame this dilemma with a radical plan to build a bigger hall literally over and around the existing premises. While building proceeded, the shows continued with no loss of income, and when the new, larger outer shell was complete, the inner walls were removed. It was a seamless transition, and the plush new Canterbury Music Hall was open for business just before Christmas 1854. It was a sumptuous sight, with a horseshoe-shaped balcony supported on pillars and accessed via a grand staircase. Chandeliers hung from the ceiling, and on either side of the imposing stage stood a harmonium and a grand piano. At a long table immediately below the stage the chairman sat with ‘’is ’ammer in ’is ’and’, his cigar and a bottle of wine.

Admission was sixpence to the body of the hall, and ninepence to the gallery. Tables seating four or more patrons were set in neat rows on the ground floor, where customers could eat and drink for a shilling and men could smoke pipes or cigars. No food or drink was served in the gallery, which made the extra threepence a worthwhile expense to the fastidious. Lavishly printed programmes announced the running order for the evening, and included the words of the songs, to encourage the audience to join in the choruses. The regulars loved it, and the increased capacity of fifteen hundred meant that they were soon joined by those who had previously been unable to get seats. Demand was enhanced by the extension of street lighting and the introduction of horse-drawn omnibuses, which allayed fears over venturing far in the dark evenings.

Morton continued to engage the best artistic talents. One of the cleverest was the Scotsman Tom Maclagan, who could sing in any style, serious or comic, dance and play the violin. Sam Collins was a regular, as was E.W. Mackney – billed by Morton as ‘the Great Mackney, Negro Delineator’ – one of the first artistes to ‘black up’ and sing what in those days were known as ‘coon’ songs. Among the popular female singers, billed with Victorian formality, were Miss Pearce, Miss Bramell and Miss Townley.

An additional attraction was a ‘fine arts’ gallery. Morton had noted the success of the National Gallery, which had opened a quarter of a century earlier and attracted ‘respectable’ society. Nor did he fail to notice the popularity of the picture gallery at the Grapes in Southwark Bridge Road. He had no scruples in stealing its ideas and improving on them. At first the paintings were lent to Morton by art dealers, but as profits rose he bought some of them. The gallery was not a personal indulgence, it was good business. Morton bought fine paintings in such quantity – including Gainsboroughs and Hogarths – that by 1856 he needed an annexe to house them all. This was celebrated in Punch as ‘the Royal Academy over the Water’, and the publicity was a further boost to Morton’s reputation.

It was in fact much more than a picture gallery, containing a reading room with books, periodicals and newspapers. Oysters, chops, baked potatoes, and bread and butter were among the refreshments that were eagerly consumed for the price of a sixpenny refreshment ticket. The gallery was open seven days a week, including Sunday night – a privilege granted to Morton, presumably because of his reputation, that caused resentment among other theatre managers denied the same indulgence.

Morton continually sought to widen the entertainment he offered. To the usual fare of ballads, comic songs, madrigals and glees, Morton – who had a great admiration for the celebrated Swedish soprano Jenny Lind – added selections from opera. Popular arias from Il Trovatore, La Traviata, Lucia de Lammermoor and Un Ballo in Maschera became a regular part of the evening’s entertainment, sung by Augustus Braham, Signor Tivoli and Miss Russell, an excellent dramatic soprano and a favourite of the audiences. Gounod’s Faust, premiered in Paris in 1859, had never been heard in England, and proved to be a popular sensation when Miss Russell sang excerpts from it. Contemporary rumour suggested that Colonel Mapleson, manager of Her Majesty’s Theatre in the Haymarket, brought the celebrated German prima donna Thérèse Tietjens to the Canterbury to see if Faust was worthy of his stage. An opera making its British debut in a music hall added to Morton’s reputation, and helped lure fashionable and wealthy patrons across the river to the dank location of the Canterbury.

Morton was an influential figure in music hall for the rest of his long life. He was probably the first to offer the complete music hall experience, although others were not far behind. His reputation was built on his early work, and enhanced by charitable hindsight. He was a kindly man, bow-tied, long-jawed and with muttonchop whiskers framing his friendly face. On his eightieth birthday in 1899, many prominent members of the profession paid warm tributes to him. An ode recited by Mrs Beerbohm Tree gives the flavour:

His Harbour Light was a vista view of things as they ought to be,

The pleasures of England should be pure and Art, it must be free

He took with pluck this parable up, at Duty’s bugle call

And swore he would lead to paths of peace the dangerous Music Hall!

This depicts Morton as a cross between Sir Galahad and Mr Valiant-for-Truth. He was a good and honourable man, but above all he was an astute businessman with an eye on the main chance and the bottom line. His virtues were real, but were puffed up in a rose-tinted biography by his friend and admirer H. Chance Newton, which was published in 1905, just after his death. In it, Morton is celebrated as the ‘Father of the Halls’. The appellation stuck. Morton’s record was remarkable, and he has an honoured role among the founders of music hall.

5

Explosion (#u7d2b65db-34ec-5f6b-b39e-e51127a2107f)

‘I have seen the future, and it works.’

LINCOLN STEFFENS, JOURNALIST (1866–1936)

The opening of the new Canterbury was the moment when music hall put down firm commercial roots, even though its golden age lay over a quarter of a century ahead. In the early 1850s the greatest names of music hall were either children or not yet born. The road from the Canterbury to the popular memories they would engender, and to the great empires of Moss, Stoll and Thornton, was long and thorny, but at the end of it lay stars still fondly remembered, and songs that have endured.

Music hall was a new industry that needed a support structure. New theatres were built in every part of the country, requiring architects, builders and designers. Singers, musicians and songwriters were needed for these theatres. Lawyers were employed to advise on the awkward legal division between legitimate theatre and music hall. Disputes over matinées and Sunday performances had to be settled. Health and safety regulations had to be met.

Taverns, concert halls and song and supper clubs were converted into music halls, and Charles Morton soon had rivals. The most formidable was Edward Weston, owner of the quaintly named Six Cans and Punch Bowl tavern in Holborn, who purchased two adjacent properties and in November 1857 opened the purpose-built Weston’s Music Hall on the site. It was launched amid huge publicity, with an elegant dinner for three hundred guests and a little theatrical larceny: Weston engaged the former chairman of the Canterbury, John Caulfield, as his musical director, and Sam Collins as his star attraction. Contemporary advertisements suggest the setting was sumptuous, with high-quality fixtures, fittings, food and drink, all for an entrance fee of sixpence. It was a none-too-subtle declaration of war, and Morton was swift to respond.

Being at Holborn, Weston’s was on the threshold of the West End, where music hall had not yet penetrated. The challenge was irresistible for Morton. In partnership with his brother-in-law Frederick Stanley he bought a seventeenth-century inn, the Boar and Castle, on the corner of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road. Despite a legal challenge from Weston, whose music hall was only a few hundred yards away, Morton built the Oxford Music Hall on the site, and opened it in March 1861. Constructed in the Italian style and reputedly costing £35,000, it was the most glamorous music hall yet, described by the early music hall historians Charles Stuart and A.J. Park as ‘a point of architectural beauty’. One of the chief features was the lighting, with twenty-eight brilliant ‘crystal’ stars. Its huge capital cost notwithstanding, the Oxford was a highly commercial proposition, with a restaurant area in the auditorium offering sufficient space for 1,800 customers to eat and drink in relays until 1 a.m., served by attractive barmaids. This was typical Morton: the best artistes packaged in an environment with fringe attractions.

At the Canterbury, the additional lure had been an art gallery and library; at the Oxford it was attractive barmaids and bars decorated with flowers. The Oxford also offered Morton an important revenue saving: from the outset he employed the same stars to sing opera selections for both the working-class audience at the Canterbury and the more cosmopolitan customers at the Oxford, transporting them between the two venues in broughams. As at any one time they might include a tenor (Mr St Aubyn), a bass (Mr Green), a soprano (Miss Russell), a contralto (Miss Walmisley) and a mezzo (Miss Fitzhenry), it is evident that a great deal of serious music was juxtaposed with more familiar music hall fare. John Caulfield was recaptured from Weston’s as resident chairman, and his son Johnny was one of the pianists. Miss Fitzhenry enjoyed early success singing ‘Up the Alma Heights’, which delighted every soldier in London, and ‘Launch the Lifeboat’, which enchanted the naval men. With other performers including George Leybourne, Tom Maclagan, Nelly Power and ‘Jolly’ John Nash, all tastes were met.

One of Morton’s innovations at the Oxford was foiled by the magistrates. When he tried to stage matinée performances on Saturdays, he was warned that his licence permitted him to open only after 6 p.m. He had to drop the idea, only to see it become common practice a few years later.

Although the Canterbury, Weston’s and above all the Oxford remained pre-eminent, competition was growing as music halls of every size were opening all around them. In 1860 the South London Palace, designed internally to resemble a Roman villa, opened at the Elephant and Castle, with the black-faced E.W. (‘the Great’) Mackney topping the bill. Harry Hart’s Lord Raglan at Bloomsbury also made its debut, followed swiftly by John Deacon’s Music Hall at Islington, with Fred Williams as chairman.

The former chimney sweep Sam Collins, one of the early stars at the Canterbury and the top of the bill at Weston’s, opened establishments of his own: the Rose of Normandy public house in Edgware Road, alongside which he built the Marylebone Music Hall. At the beginning of his musical career Sam had earned a few shillings a night as a pub singer; in 1863, at the age of thirty-five, he became the respected and much-loved owner of the newly built Collins’ Music Hall in Islington, known colloquially as ‘the Chapel on the Green’. Sadly, Sam was able to revel in his new status only briefly, for he died two years after it opened. He was one of the many music hall pioneers who did not live long enough to enjoy the rewards of the trail they had blazed.

In 1859 the London Pavilion was opened in Tichborne Street, Haymarket, by Emil Loibl and Charles Sonnhammer. Originally a stable yard, it had been converted to the Black Horse tavern two years earlier, run as a song and supper room, and then rebuilt as the much more substantial London Pavilion, with an audience capacity of two thousand. It became the home of variety under Sir Charles (C.B.) Cochran, and would end its life as a cinema three quarters of a century later. But the intervening years wove it into the fabric of music hall history.

The boom continued throughout the 1860s with the debut of the Alhambra Palace, Leicester Square, together with the Bedford Theatre in Camden, immortalised in oils by Walter Sickert. The Royal New Music Hall, Kensington, the Royal Standard at Pimlico, the Oxford & Cambridge in Chalk Farm, the Regent in Regent Street, the Royal Cambridge in Commercial Street, Whitechapel (where Charlie Chaplin is thought to have made his debut as a soloist) and Hoxton Music Hall all opened in 1864. Gatti’s-in-the-Road, in Westminster Bridge Road, and Gatti’s-under-the-Arches, in Villiers Street, opened in 1865 and 1867 respectively. The latter year brought the Panorama in Shoreditch, Davey’s at Stratford, the Royal Oriental at Poplar and the opening of the Virgo, otherwise the Varieties Theatre, Hoxton. Later known as the Sod’s Opera, this was a seedy, rowdy hall with an insalubrious audience. The pace slowed thereafter, but new building continued. By 1875 London hosted thirty full-time music halls, and double that number by the turn of the century.

Outside London, public demand for music hall was similarly fierce. Old taverns and ‘free and easies’ had been swiftly adapted: the Adelphi in Sheffield had formerly been a circus, and Thornton’s Varieties in Leeds a harmonica room. In Sheffield, the curiously named Surrey Music Hall – formerly a casino – opened in 1850, and proud locals pronounced it to be the most handsome in the country; sadly, it burned down in 1865. Undaunted, its owner, a former Irish labourer, Thomas Youdan, took over the Adelphi and opened it as the Alexandra Music Hall. Manchester boasted the Star at Ancoats, ‘the People’s Concert Hall’, which had opened in the early 1850s, and the London Music Hall in Bridge Street.

The old ‘free and easies’ in Nottingham had built up a huge appetite for music hall, and the venerable and grubby Theatre Royal in St Mary’s Gate was renovated as the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties. A little later St George’s Hall attracted local audiences. Its resident chairman was Harry Ball, father of music hall’s greatest male impersonator, Vesta Tilley, who made her debut there in 1868, aged four. Music hall made its Scottish debut with the Alhambra in Dundee, although Scottish old-time music hall continued to centre on Glasgow.

All of the theatres that followed the opening of the Canterbury faced many of the same problems. One was the law. By sharpening the distinction between drama and music hall the 1843 Theatre Regulations Act had opened up opportunities, but it presented problems too. Charles Morton’s experience was higher-profile than most, but was not unique. The Canterbury¸ as a music hall, was unlicensed for drama, but at Christmas 1855 Morton staged a dramatic sketch which, under the absurdities of the Act, was illegal. Rival managers, keen to undermine him, pounced, and Morton was hauled before the local magistrates. He lost the case on the flimsy grounds that the sketch had two speaking parts; if one actor had played both roles it would have been legal.

Such trivial prosecutions were to continue spasmodically until 1912. Morton suffered again when he staged an abbreviated version of The Tempest and was fined a nominal £5 by a reluctant magistrate who had seen and enjoyed the show. But, as he pointed out to a disgruntled Morton, the law was the law. Law or not, it was often flouted without action being taken, especially in the less fashionable halls that posed no threat to legitimate theatre. But the banning of drama did have the beneficial side-effect of preserving undiluted music hall fare in the halls.

Morton’s mini-drama over The Tempest had one lasting consequence. The Times reported the court case, and in doing so described the performance. This was the first time the foremost newspaper in the land had acknowledged the existence of music hall. Once it had done so, Morton, seeing an opportunity, offered it an advertisement for his theatre. The Times, perhaps acknowledging the force that music hall was to become, accepted it. Other theatres followed suit, and a new advertising outlet was born, assisted by the abolition in 1853 of tax on press advertisements.

Despite Morton’s foray into the fashionable West End, and The Times’s preparedness to accept his money, music hall was not yet respectable, nor would it be for many years. Some strands of opinion regarded it as a malign influence on the working man. In 1831, the Lord’s Day Observance Society had been established to combat ‘the multitudes intent on pursuing pleasure on the Lord’s Day’. The society’s members, led by the vicar of Islington, whose parish was not far from the heartland of enthusiasm for music hall, had in mind such wickedness as coach and steamboat trips and visits to tea rooms and taverns. The vicar’s concern was that such indulgences would ‘absorb much of the money which should contribute to the more decent support of wives and children’. It is not clear when the society thought the working man – whose only day for leisure was Sunday – should enjoy himself, or whether he should at all. In any event, the society was to be a powerful and hostile lobby throughout the life of music hall.

But the killjoys had powerful opposition. In 1836 Charles Dickens wrote a biting pseudonymous essay, ‘Sunday Under Three Heads’, mockingly dedicated to the Bishop of London: ‘The day which his Maker intended as a blessing, Man has converted into a curse. Instead of being hailed by him as his period of relaxation, he finds it remarkable only as depriving him of every comfort and enjoyment.’ Others agreed. A current song commented:

No duck must lay, no cat must kitten,

No hen must leave her nest, though sittin’.

Though painful is the situation