По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

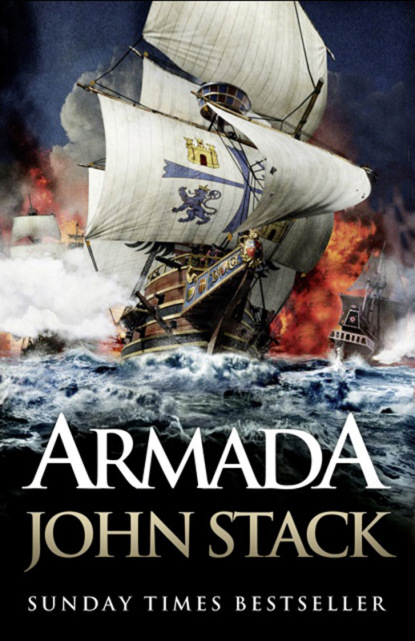

Armada

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In the quiet of the cell Evardo pictured his mentor in his mind’s eye. The image brought a flash of anger to his heart but then he thought of the years of comradeship and support that Abrahan had given him. Under his tutelage he had crossed the world, making the leap from boy to man. In many ways Evardo had come to consider Abrahan as the father he had lost to war. As a comandante he was accustomed to a solitary existence but for the first time he felt very alone. The feeling sickened him.

In the darkness he closed his hand into a tight fist. The shame of his defeat threatened to overwhelm him, to unman him in that black space, but with savage determination he crushed his regret. Evardo gave his mind over to the boom of the waves striking the hull and the creak of timbers. The journey ahead would be long, but eventually he would return to Spain, and he focused his thoughts on that day. Using the powerful influence of his family he would seek another galleon command. His honour demanded nothing less. Only then would he be able to take the first step in fulfilling the vow that had now become the centre of his being: revenge.

Above the swirling mists of gun smoke surrounding the English fleet in the waters off Sagres, a lookout on the Elizabeth Bonaventure spotted the raising of a white flag. He shouted it down to the quarterdeck and across the fleet the order was given to cease fire. In the quiet that followed, Robert looked out across the untroubled waters to the town’s castle. The bombardment had lasted a mere two hours, a savage cannonade that had pierced the battlements in several places and silenced the garrison’s return of fire. Black smoke was rising from within, billowing past the crude flag of surrender, and on the gentle breeze Robert could hear the desperate cries of a cornered populace.

‘Ho quarterdeck, Cygnet approaching on the starboard beam.’

‘Ahoy, Captain Varian.’

‘Ahoy, Captain Bell,’ Robert shouted back, raising his arm.

‘Orders from the Elizabeth Bonaventure, Captain,’ Bell called. ‘You are to tranship eighty men to the Cygnet to join the shore party. Commander Drake has already gone ashore to accept the surrender of the Spanish garrison.’

Robert acknowledged the command and ordered the boatswain to the quarterdeck.

‘Mister Shaw, call out and arm the men of the dog watch. Have them assemble on the main deck.’

Seeley approached as Shaw’s voice rang out across the Retribution.

‘With your permission, Captain,’ the master said, ‘I’d like to join the shore party.’

Robert considered the request. He had already decided, despite his injury, that he would be going ashore. The Spy and two other pinnaces were patrolling five miles further out to sea, providing a screen for the landings. Any approach by hostile ships would be spotted well in advance. He looked to Seeley, seeing the justifiable eagerness on his face given the drubbing he received at Lagos. He smiled.

‘Permission granted, Mister Seeley. Inform Mister Shaw that he will have command of the Retribution while we are ashore.’

‘Thank you, Captain,’ Seeley replied with a roguish grin. He hurried after the boatswain, adding his voice to the call for order on the main deck.

Moments later the Cygnet pulled away from the galleon and turned sharply around its stern. Across the sweep of the fleet, a flotilla of pinnaces was sailing in towards the small port, their decks crammed with men. Robert stood on the bow of the Cygnet, his balance shifting with the fall of the deck. Behind him were the chosen men of his crew, their silence a thin veneer that scarcely concealed their expectation.

They were heavily armed but few men were identically equipped. Robert wore a breastplate of armour, as did over a dozen of his crew. Many of these were cast-offs from previous battles while others wore morions, the ubiquitous helmet of European soldiers. Each man had a sword and at least one dagger and while the primary weapon of the majority was an arquebus gun, the more hidebound veterans were armed with halberds, bills and crossbows. Only two men carried longbows, weapons they had known since childhood and could never be relinquished for another.

Robert bore one other unique firearm, a wheellock pistol, an expensive weapon that he had found amongst Morgan’s belongings and he unconsciously fingered the elaborate mechanism as he thought of the man who had previously led the crew behind him into battle.

He looked ahead to the surf-worn beach that skirted the edge of the town. A lone boat was beached there: Drake’s launch. Beyond it Robert spotted the fleet commander appear from the town with an escort of heavily armed soldiers. Walking with him was a Spaniard, evidentially the garrison commander.

The longboats rode in through the surf and disgorged their men onto the beach before returning to the pinnaces to gather more. Robert went in with the first of his crew and jumped out into the crashing waves as the boat touched bottom. The cold water helped to ease the throbbing in his leg and he waded ashore.

Within twenty minutes seven hundred English landed, gathering in motley ranks behind their commanders. All the while Drake stood immovable at the head of the beach, his head turning slowly as his gaze ranged over the men. Robert could see he was talking to the Spanish commander out of the corner of his mouth, his expression solemn and imperious. Drake was not physically striking, and his dark curly hair and fairer beard made his age hard to determine. He projected a definite air of authority that belied his humble beginnings, and his gaze was penetrating and direct.

A sense of awe never failed to affect Robert when he was in Drake’s presence. He was the first Englishman to circumnavigate the world, an explorer and privateer who commanded the Queen’s deepest affections and God’s own luck. That four out of five ships had been lost during his circumnavigation and Drake had executed his friend for mutiny mattered little. The Golden Hind had returned brimming with gold, silver, spices, and precious stones that netted a near fifty-fold profit for the crown and a knighthood for Drake. To sail with Drake was to benefit from his uncanny ability to survive and profit and the men behind Robert fell into expectant silence as their commander stepped forward.

‘Men!’ he shouted, his hand sweeping out over Sagres. ‘The town is yours. Take it.’

The men erupted in a savage cheer, surging forward like a pack of baying wolves. They attacked, streaming up the beach and between the outlying buildings, jostling angrily at the choke-points as all sought to be the first to savour the plunder of the town.

Robert went with them, his slower pace making him the victim of shouldered charges as men ran around him. One struck him heavily and he was about to fall when a hand grabbed his upper arm to steady him. It was Seeley. Robert smiled amidst the cheers as the last of the crew of the Retribution passed them. They reached the whitewashed houses that marked the edge of the town and Robert became aware of the new sound beneath the cheering Englishmen – the tortured screams of the population. Shots rang out from all sides as sailors and soldiers began to kill all who stood in their way.

Robert drew his wheellock pistol from his belt. He held it loosely in his hand and looked left and right down the narrow side streets. The door of every house and hovel was open. The raiders were everywhere, streaming from one place to another, many with booty already in hand. Others stood drinking and carousing, laughing wildly as they upended any bottle they could find. The shrieks of women could be heard above everything and Robert saw one attempt to flee from a house only to be chased and run down by a sailor who dragged her back inside.

He looked at Seeley walking beside him. The youth’s face was pale, his eyes darting everywhere at once, and his mouth was whispering unintelligible words. Robert had witnessed the aftermath of a sacking many years before on the Spanish Main, and his time spent on the slave trade had long since hardened him to the cruelties of men. From Seeley’s expression, he could only devise that this was the young man’s first experience of the fate that awaited every civilian at the hands of an army let loose.

Cheering could no longer be heard. Instead the air was filled with terrible sounds that seemed to emanate from the pit of Hades, the cries and wailing of a people given over to the base desires of men toughened in the forge of battle. The infrequent crack of an arquebus mixed with the angry shouts of Englishmen, fuelled by wine and avarice, fighting over the meagre offerings of the small town. The dead lay everywhere, the men shot or run through with steel while the women had been raped, beaten and discarded. The terror of their final moments was still etched on their faces.

Robert and Thomas reached the main square. On one side the western face of a small church stood tall above the buildings flanking it. A group of men were at the doors, trying to force them open. Without hesitation Robert rushed forward. He switched his pistol to his left hand and drew his sword. Seeley followed, surprised by the sudden haste. The square was in chaos with men running in all directions, but Robert kept his course firmly fixed on the church door, his face twisting in anger, the pain in his leg forgotten.

‘Hold,’ he shouted, charging his sword before him.

The sailors turned and brought their own weapons quickly to bear.

‘Piss off, sailor,’ one of them snarled, ‘’less you want your blood spilled. This here’s our place.’

Seeley came up. Once he had seen the captain’s destination he had understood immediately and the anger he saw on Robert’s face confirmed it. He felt his own religious fervour rise within him.

‘Captain Varian, maybe there’s another way in,’ he suggested.

‘Captain Varian …’ one of the men repeated and the others lowered their weapons, mindful of the tale they had heard of the captain’s charge on the Spanish galleon. Their expressions remained belligerent, suspicious that the officers had intervened so they could claim whatever plunder was inside for themselves.

Robert’s mind was in turmoil. He had rushed to the church door to defend it without thinking. Then he realized he could not, for how would he explain his actions? He felt the weight of the sword and pistol in his hands. This was a Catholic church. He should defend it. But he was the commander of a Protestant crew. He could not justifiably stop them, not without coming close to revealing his faith.

‘Who’s inside, men?’ Seeley asked, stepping forward.

‘Some shit stinkin’ priest,’ one of the sailors replied. ‘We saw him close the door as we came into the square.’

‘We want into that strong box that papists have in their churches,’ another said, referring to the tabernacle, and the others voiced their agreement, one of them taking up the shout again for the priest inside to open the doors.

Seeley took charge, ordering two men to find something to ram the door. They returned moments later with a stout wooden bench. The men attacked the door with unbridled aggression and the boom of the battering ram brought more men from around the square. The timbers of the door gave way under the onslaught and the sailors cheered as they pushed their way through. Robert tried to shoulder his way in with the leading edge of the charge, anxious to protect the priest inside, believing that he could somehow excuse his mercy later.

The sailors spilled into the church, the original group in the lead. Their anger and haste were heightened by the dozens of men at their rear, knowing the spoils they sought were under threat. Robert stumbled in. His eyes searched frantically in the gloom of the interior for the priest. The Spaniard was running up the centre aisle, sailors on his heels. Robert watched in horror as one of them raised his arquebus. He swung up his own pistol, bringing it to bear on the sailor’s back. He hesitated and the pistol shook in his hand. A second later a blast rang out. The sailor had shot the priest at near point-blank range. His head snapped forward under the hammer blow of the lead ball before he fell to the floor.

‘You men,’ Seeley roared near at hand. ‘Tear down those statues.’

Robert spun around, his rage threatening to slip its bonds. The men quickly desecrated the church, pulling down the ornate statues and smashing them underfoot, while the air resounded with the clang of metal as the sailors attacked the tabernacle doors with their weapons.

‘Blasphemous idolaters,’ Seeley cursed.

Robert was possessed by the urge to run the man through but he turned and walked out, unable to trust himself in the face of such destruction. He stood with his back to the church and looked out over the square. Suddenly he became conscious of the pistol in his hand and he stuck it back in his belt. He had thought nothing of the destruction of the town and the massacre of the population; the Spanish were enemies. But the threat against the church and the priest had driven him to the brink of drawing English blood.

He had not, but the shame of witnessing such an attack and doing nothing to prevent it began to consume him. He walked away, anxious to get back to the Retribution and find solitude to calm the rancorous voice of his conscience. In his heart he was already convinced it was a hopeless cause.

Seeley watched the captain leave from inside the church doors. He was breathing heavily and his heart raced from the righteousness that had taken hold of him. He was cleansing the church for God, ridding it of its idols and graven images. Although he knew many of his men sought only plunder, others had responded instantly to his order to tear down the statues, answering the call of their faith.

The captain too had answered that call and Seeley remembered the haste he had witnessed when they first encountered the church, the aggressive way Varian had pushed through when the door had been breeched and how he had raised his pistol to shoot the priest. But then the captain had hesitated. His furious expression had been a sight to behold, an outward sign of his religious ardour yet, Seeley marked, he had not taken command of the men, nor stayed to watch the faithful propagation of God’s will. Seeley had also heard the accounts of the captain’s fearless charge on the Halcón, but again of how he had spared the Spanish captain. While he had no doubt that his captain was committed to the cause of defeating Spain, Seeley could not help wondering if Varian’s religious convictions matched the depth of his nationalist loyalties.

It was a deficiency Seeley had witnessed in others, an imbalance that placed the Queen above God and put the needs of England ahead of those of the Divine. Varian’s actions bore witness to the tenets of his Protestant beliefs which triggered his impulse to attack the idolaters’ church and shoot the priest, but for Seeley such religious instincts ran deeper.

When Seeley had first entered the town he had been sickened by the depravity he had witnessed in the streets and it had taken all his will not to vomit up the bile that had risen in his throat. But then he had remembered the defeat at Lagos. The Spaniards deserved no mercy. In the fight against the scourge of Roman Catholic heresy there could be no hesitation, no half-measures. He turned once more to look upon the ruin of the church interior and realized it was his duty to instil in every man he could influence the will to wage unconditional holy war against the papist foe.

CHAPTER 5