По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

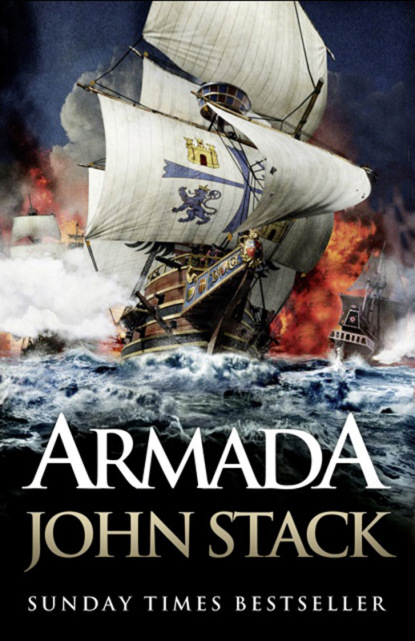

Armada

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The story of Robert’s charge on the Halcón had spread rapidly throughout the English fleet and that action, coupled with his natural selection as second-in-command, had secured him a field promotion to captain. Drake himself had come from his flagship to confer the honour, bringing with him his chaplain, and the commander of the fleet had ordered a double ration of grog for the entire crew in recognition of their fight, prompting a cheer from the bloodied men of the Retribution.

There was a knock on the cabin door and Seeley entered.

‘Well?’ Robert asked, sitting up straighter.

‘Six dead and nine wounded,’ Seeley replied, ‘and I fear two of those will not see tomorrow’s dawn.’

‘Who are they?’

Seeley listed the names and Robert repeated them silently to himself.

After Cadiz the fleet had sailed south to the Algarve coast and the fortified town of Lagos. The English had anchored five miles from the town and Drake had quickly assembled a landing party of a thousand men, taking one hundred from the Retribution. Owing to Robert’s injury Seeley had taken charge of the Retribution’s levy and Robert had watched them march away, only to see the badly mauled ranks return a day later.

‘A pox on the Spaniards,’ Seeley spat, pacing the cabin, ‘they led us all the way to the walls of Lagos before revealing their true strength.’

‘We were lucky to escape so lightly,’ Robert remarked, conscious that the fleet had been badly exposed while waiting at the landing point.

‘It was God’s will, Captain, not luck,’ Seeley corrected, ‘and He has opened our eyes to the perfidiousness of the enemy. We will not be so easily deceived again.’

‘We will soon have cause to test that wisdom,’ Robert said, leaning forward to offer Seeley a drink. The new master of the Retribution sat down, his expression questioning.

‘The order arrived while you were below decks,’ Robert explained. ‘We are sailing to Sagres and Drake means to take the town.’

Seeley smiled and picked up the goblet from the table, swirling the wine within.

‘Rejoice not over me, O my enemy,’ he recited, ‘when I fall, I shall rise; when I sit in darkness, the Lord will be a light to me.’

Robert nodded, recognizing the quotation from the bible.

‘It is a small port, but strategically important.’ He put his goblet down to lean in over the table, wincing slightly as he shifted his leg. He pulled an opened chart across and Seeley stood up to study it. It was a detailed map of the south-western coastline of Portugal. Together they pored over the annotations regarding Sagres and its approaches.

A hurried knock on the door interrupted them and the ship’s surgeon entered without awaiting permission. His face was agitated and he advanced with his hand outstretched before him.

‘What is it, Mister Powell?’ Robert asked, consciously suppressing the unwanted memories resurfaced by the unexpected arrival of the surgeon.

Powell was one of the oldest members of the crew. He was a tall man but his back was curved from a lifetime of treating wounded men. He wore a heavy leather blood-stained apron and his arms were stained pink to the elbows.

‘I found these in the surgery.’ Powell opened his hand to reveal a silver crucifix and marble statuette of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Seeley shot out of his chair. For the briefest moment his and Powell’s full attention was on the artefacts alone. Robert knew his face betrayed the depths of his distress at the sudden revelation. He gathered his wits as Powell advanced further and looked down at the blood stained pieces the surgeon slammed onto the table.

‘Papist icons,’ Seeley breathed. He rounded on Powell. ‘Where exactly did you find them?’

‘Under my table. They were hidden under a pile of bloodied rags.’

‘Who dropped them?’ Seeley took a step towards the surgeon, his hand falling to the hilt of his sword.

‘I don’t know.’ Powell glanced at the master’s sword hand but remained unperturbed. A lifetime of serving aboard ship had made him immune to young men like Seeley. ‘Dozens of men have been in and out of my surgery over the past twenty-four hours, both the injured and those who carried them. Where I found those,’ he looked to the icons, ‘hidden away like that, well, they could have been there since Cadiz.’

‘A traitor,’ Seeley said vehemently, turning to Robert, ‘a Roman Catholic spy, Captain, on board the Retribution.’

Robert held out his hand to quieten Seeley. He focused on keeping it steady. He looked again at his father’s icons, furious with himself for not thinking of them earlier. Perhaps it was the pain of his wound or the pace of events since Cadiz, but whenever he had recalled his time in the surgery, he had failed to register the significance of his breeches being cut away and discarded.

He glanced at Seeley and Powell.

‘Who else knows of this?’

‘Only you and Mister Seeley here, Captain. I came straight to your cabin when I found them.’

Robert nodded. His best chance of suppressing any hunt was now, before it began.

‘Then we will keep it that way,’ he said.

‘What? Why?’ Seeley’s eyes narrowed.

‘Because, Mister Seeley,’ Robert replied authoritatively, ‘I do not wish to have my ship rife with suspicion until we are clear on the facts. Indeed, there may be a simpler explanation as to why Mister Powell found these icons on board. They may have been taken as plunder from a Spaniard.’

Seeley made to speak but the surgeon interjected. ‘I thought that too, Captain, but then I discovered that both of these icons are inscribed with an English name.’

‘Why didn’t you say before, you fool!’ Seeley rounded on the surgeon angrily. ‘You mean to say that the traitor’s name is on the icons?’

‘No, Mister Seeley,’ Powell said. ‘For the name inscribed is not of any man on board. See here.’

He picked up the crucifix and, turning it over, rubbed his thumb along its length to remove the film of blood.

‘There is the name: Young.’

Evardo kicked out in the darkness at the creature. The scurrying sound stopped. The rat was close, maybe inches away, and he kicked out again. The rat screeched and scuttled away. Evardo sat up. His mind was dull with fatigue but still he was unable to sleep. His skin crawled as he felt the cockroaches scurry beneath and around him. He rubbed his hand over his face, massaging his forefinger and thumb into his eyes. When he opened them again he focused on the thin shafts of light that penetrated through the cracks in the door of the cell.

He was not alone. There were four other men held captive with him in the forward section of the orlop deck of the English flagship. He listened intently as one murmured incoherently, trapped in some horrible nightmare that would not be relieved by waking. Evardo licked his lips. His mouth was dry and scummy and he reached out for the pail of water, his hand swinging through a slow arc in the darkness until he touched its rim. He picked it up and scooped his hand in, bringing the foul brackish liquid up to his mouth. It did little to quench his thirst. For a moment he was tempted to toss the pail away in anger before thinking better of it, knowing how severely the precious liquid was rationed.

When he had first been brought to the Elizabeth Bonaventure he had been formally welcomed by the captain of the English flagship. El Draque, disappointingly, had not been on deck, and Evardo had listened bitterly as the captain explained in halting Spanish the terms of his capture. He was to be brought back to England where he would be held until a ransom was paid for his release. It was an ignominious fate, one that would be shared by the four other men of noble birth who shared his quarters in the ship’s bowels.

Evardo kept his gaze locked on the shafts of light. They swung slowly with the roll of the ship, sweeping across the near pitch darkness of the cell. He held out his right hand, his sword hand, to allow the feeble light to catch it. He vividly recalled that moment on the Halcón after he had handed over his weapon to the Englishman, Varian. Since then, and with a deep sense of shame, he had asked himself if he should not have fought on and accepted the price of death for his honour.

After Varian had walked away from him, he had been jostled, along with the rest of his crew, into the fo’c’sle. His first reaction had been to look for Abrahan. When he saw the older man push through the throng to approach him, he had begun to smile, glad to see his old friend safe. That smile had died on his lips when he beheld the murderous look on Abrahan’s face.

‘You cursed cobarde,’ he had hissed, and Evardo had recoiled from the accusation of cowardice.

‘I was bested, there was nothing I could do, the fight …’

‘You surrendered your ship like some Portuguese hijo de puta and betrayed your command and your crew!’

‘Betrayed?’ Evardo had hissed back, dropping his hand to clasp the sword that was no longer by his side. ‘After the English counter-attacked, there was nothing we could do, you know that.’

‘Then you should have paid for the loss of the Halcón with your blood, not your sword.’

Evardo had made to reply, but Abrahan had turned his back on him, pushing through the surrounding crewmen who had heard every word of the exchange. Evardo had looked at them, and while many had averted their gaze, others had stared back with accusing eyes, persuaded by Abrahan’s words that their captain had indeed betrayed the Halcón and its crew.