По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

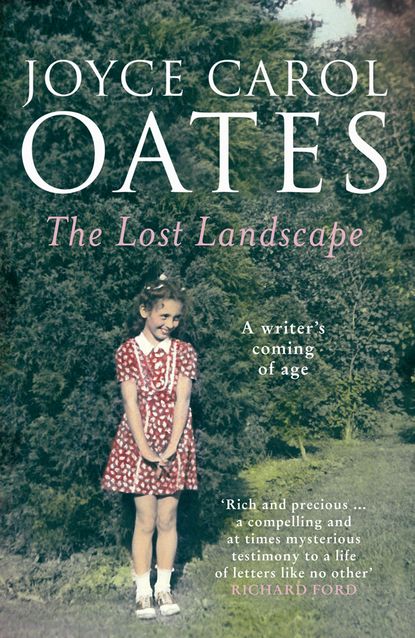

The Lost Landscape

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In her harsh guttural speech the Grandmother would curse the chickens and the rooster. Much of the Grandmother’s speech had a sound of chiding and cursing. And the Grandmother would take up the limp blood-dripping hen-corpse into the kitchen and boil a pan of water on the stove and drop the hen-corpse into it, so that the feathers could be plucked more easily.

At these times the little girl had run away and hid her eyes.

The Mother would say to her, Don’t pay any attention, help me in the kitchen, sweetie!

Mostly the little girl would not remember such things. The little girl’s memory of the farm on Transit Road was very selective like the colander into which the Grandmother dumped boiling water containing her thin-cut noodles, made out of the Grandmother’s noodle-dough, that trapped just the noodles but strained away the liquid.

In later years recalling with a fond smile very little of the farm, the barnyard, the flock of Rhode Island Reds—just, me.

THE LITTLE GIRL WAS so excited! She was five years old.

This was the summer the little girl was allowed to help the Grandmother collect eggs from the hens’ nests in the chicken coop (where the chicken droppings were so smelly, you had to hold your breath especially after a rain) and soon then, the little girl was allowed to feed the chickens by herself, twice a day, their special chicken-feed. Like tiny pebbles the chicken feed seemed to the little girl, seized in handfuls to toss to the chickens; to get the seed you lowered a tin pie pan deep into the feed-sack, itself contained inside a larger, canvas sack to keep out rats and mice.

So exciting! Almost, the little girl wetted her panties, with anticipation.

And when she began to call to the chickens in her high, quavering voice as the Grandmother had taught her—CHICK!-chick-chick-chick-chick-CHI-ICK!—chickens came rushing in her direction at once, and made the little girl feel very special—very powerful. It was not ever the case that the little girl felt powerful—nor could the little girl have defined the sensation, at the time; but calling CHICK!-chick-chick-chick-chick-CHI-ICK provoked such a feeling in her, set her heart to pumping and a warm, rich sensation coursing through her veins, the little girl felt very special, and very proud.

Oh, she could see—(for she was a quick-witted, smart little girl)—that the chickens were oblivious of her, in their greed to devour seed they took not the slightest interest in her, or in their surroundings; yet still it seemed to the little girl that the chickens must like her, and knew who she was, for they came so quickly to her, colliding with one another, scolding and fretting, pecking one another in a frenzy to get to the seed the little girl tossed in a wide, wavering circle.

The Grandmother had instructed the little girl to distribute the seed as evenly as she could. You did not want all the chickens rushing together in a tight little spot, and injuring themselves. The little girl understood that she had to be fair to all the chickens, not just a few.

But the largest and most aggressive chickens rushed and pecked and beat away the others no matter how hard the girl tried.

Of course, Joyce Carol always fed me, specially. In a safe little area, by the side of the house. This was Happy Chicken’s special meal, which was served ahead of the general feeding. If other chickens noticed, and ran clucking to this meal, the little girl stamped her feet and shooed them away.

Though he might have been prowling out in the orchard, soon there came Mr. Rooster running on his long scaly legs. Mr. Rooster could hear the Chick-chick-chick! call from a considerable distance. He pushed through the throng of clucking chickens knocking the silly hens aside and gobbled up as much seed as he could from the ground. Sometimes then pausing, looking up with a squint in his yellow eyes, and made a decision—(who knows why?)—to rush at the little girl and jab her bare knee with his beak.

So quickly this assault came, when it came, the little girl never had time to draw back and escape.

Ohhh! Why was Mr. Rooster so mean!

The little girl was always astonished, the rooster was so mean.

The rooster’s beak was so swift, so sharp and so mean.

Worse yet, the rooster sometimes chased the little girl, trying to peck her legs. If the Grandmother saw, she shooed the rooster away by flapping her apron at him and cursing him in Hungarian. If the Grandfather saw, he gave the rooster a kick hard enough to lift the indignant bird into the air, squawking and kicking.

It was one of the mysteries of the little girl’s life, why when the other chickens seemed to like her so much, and her pet chicken adored her, Mr. Rooster continued to be so mean. It did not make sense to the little girl that Mr. Rooster devoured the seed she gave him, then turned on her as if he hated her. Shouldn’t Mr. Rooster be grateful?

The Mother kissed and cuddled her and said, Oh!—that’s just the way roosters are, sweetie!

Plaintively the little girl asked the Grandmother why did the rooster peck her and make her bleed and the Grandmother did not cuddle her but said, with an air of impatience, in her broken, guttural English, Because he is a rooster. You should not always be surprised, how roosters are.

THE LITTLE GIRL WANDERED the farm. The little girl was forbidden to step off the property.

There was the big barn, and there was the silo, and there was the chicken coop, and there were the storage sheds, and there was the barnyard, and there was the backyard, and there were the fields planted in potatoes and corn, and there was the orchard and beyond the orchard a quarter-mile lane back to the Weidenbachs’ farm where there were big nasty dogs that barked and bit and the little girl did not dare to go. In these places chickens wandered, and also Mr. Rooster, in their ceaseless scratching-and-pecking for food, though it was rare to see a chicken in one of the farther fields or in the lane. Happy Chicken only accompanied the little girl if she called him to these places, or carried him snug and firm in her arms.

The little girl placed me on the lowermost limb of the lilac tree by the back door of the house, so that I could “roost.” The little girl urged me to try to “fly—like a bird.” But if the little girl nudged me, and I lost my balance on the tree limb, my wings flapped uselessly, and I fell to the ground and did not always land on my feet.

At such a time I picked myself up and tottered away clucking loudly, complaining like any disgruntled hen, and the little girl hurried after me saying how sorry she was, and promised not to do it again.

Happy Chicken! Don’t be mad at me, I love you.

(IT WAS TAKEN FOR granted, it was never contested or wondered-at, that our wings were useless. We could “flap” our wings and “fly” for a few feet—even Mr. Rooster could not fly farther than a few yards; though there were wild turkeys, fatter and heavier than Rhode Island Reds, who could manage to “fly” into the higher limbs of a tree, and there “roost.”)

NOT JUST THE CHICKEN coop and much of the barnyard but the grassy lawn behind the house—(“lawn” was a name given to the patch of rough, short-cropped crabgrass that extended from the barnyard and the driveway to the pear orchard)—was mottled with chicken droppings. Runny black-and-white glistening smudges that gradually hardened into little stones and lost their sharp smell.

You would not want to run barefoot in the backyard, in the scrubby grass.

And there was the ugly tree stump along the side of the barn, stained with something dark.

And surrounding the stained block, chicken feathers. Sticky-stained feathers in dark clotted clumps.

No chickens scratched and pecked in the dirt here. Even Mr. Rooster kept his distance. And the little girl.

GRANDMA WAS THE ONE, you know. The one who killed the chickens. No! I did not know.

Of course you must have known, Joyce. You must have seen—many times. . . .

No. I didn’t know. I never saw.

But . . .

I never saw.

In later years she would recall little of her Hungarian grandparents. Her mother’s stepparents. For few snapshots remained of those years. She did know that the Grandfather and the Grandmother were something that was called Hungarian. They’d come on a “big boat” from a faraway place called Hungary years before the little girl was born and so this was not of much interest to the little girl since it had happened long ago. The grandparents seemed to the little girl to be very old. The big-breasted big-hipped Grandmother had never cut her hair that was silvery-gray-streaked and fell past her waist if she let it down from the tight-braided bun. The Grandmother had been eighteen when she’d come to the United States on a “boat” and at age eighteen it had seemed to her too late for her to learn English, as the Grandfather had learned English well enough to speak haltingly and to run his finger beneath printed words in a newspaper or magazine. The Grandfather was a tall big-bellied man with scratchy whiskers who liked to laugh as if much were a joke to him. He had rough calloused fingers that caught in the little girl’s curly hair when he was just teasing.

Worse yet was tickling. When the Grandfather’s breath smelled harsh and fiery like gasoline from the cider he drank out of a jug. But the Mother insisted Grandpa loves you, if you cry you will make Grandpa feel bad.

The farm was the Grandfather’s property. Of farms on Transit Road it was one of the smallest. Much of the acreage was a pear orchard. Pears were the primary crop of the farm, and eggs were second. The little girl and her parents lived on the Grandfather’s property upstairs in the farmhouse. The little girl understood that the Father was not so happy living there, for the Father had been born in Lockport and preferred the city to the country, absolutely. The Father had tried his hand at farming and “hated” it. The little girl often overheard her parents speak of wanting to move away, to live in Lockport, where the Father’s mother who was the little girl’s Other Grandmother lived. Except years would pass, all the years of their lives would pass as in a dream, and somehow—they did not ever move away.

There was something strange about the Grandfather and the Grandmother but the little girl could not guess what it was. Later she would learn that the Grandfather and the Grandmother were not the Mother’s actual parents but her stepparents and it was worrisome to the little girl, that in some way steps were involved. Like the long frightening stepladder that only Daddy could climb to pick pears, apples, and cherries from the highest limbs of the trees.

The little girl noticed that, when her parents were speaking together, or any adults were speaking together, if she came near they might cease speaking suddenly. They would smile at her, they would say her name, but they would not reveal what they had been saying.

The little girl ran away to hide, sometimes. When the adults were speaking sharply to one another. When the Grandfather cursed at the Grandmother in Hungarian, and the Grandmother wept angrily and hid her flushed face in her hands.

The little girl had several times seen the Grandmother’s long coarse gray-black hair straggling down her back like something alive and livid. The little girl shut her eyes not wanting to see as she shrank from seeing the Grandmother’s large soft melon-breasts loose inside a camisole, that was wrong to see for there were things, the little girl realized, that it was wrong to see and you would be sorry if you saw.

On a farm, there are many such things. Wild creatures that have crawled beneath a storage shed to die, or the bones of a chicken or a rabbit all but plucked clean by a rampaging owl in the night.

“Joyce Carol! Come here.”

With a nervous little laugh like a cough the Mother would shield the little girl’s eyes from something she should not see. Between the Mother’s eyebrows, faint lines of vexation and alarm.

“Sweetie, I said come here. We’re going inside now.”

SOMETIMES THE LITTLE GIRL was breathless and frightened but why, the little girl would not afterward recall.