По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

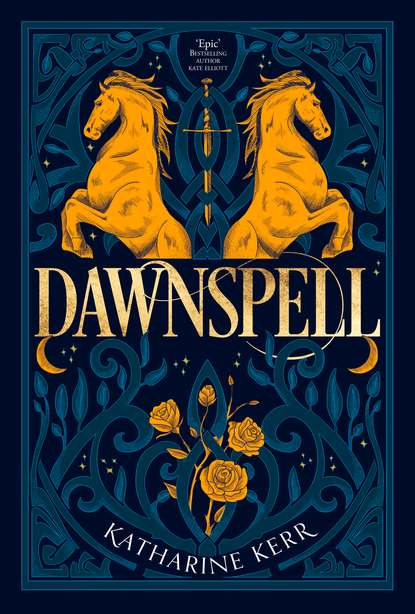

Dawnspell

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Which one of you is the bard?’

‘I am,’ Maddyn said. ‘But not much of one, a gerthddyn, truly, if that. I can sing, but I don’t have a true bard’s lore.’

‘And who gives a pig’s fart who some lord’s great-great-great-grand-dam was? This is a bit of splendid luck.’ Stevyc turned, calling out to Caradoc, ‘Here, captain, we’ve got a bard of our own.’

‘And next we’ll be eating off silver plates, like the great lords we are.’ Caradoc came strolling over. ‘But a bard would have come in handy this winter, with the pack of you causing trouble because you had naught better to do. Well and good then, Maddyn. If you sing well enough, you’ll be free of kitchen work and stable duty, but I’ll expect you to make up songs about our battles just like you would for a lord.’

‘I’ll do my best, captain, to sing as well as we deserve.’

‘Better than we deserve, Maddyn lad, or you’ll sound like a cat in heat.’

After a rough dinner of venison and turnips, Maddyn was given his chance to sing, sitting on a rickety, half-rotted table in what had once been the lodge’s great hall. He’d only done one ballad when he realized that his place in the troop was assured. The men listened with the deep fascination of the utterly bored, hardly noticing or caring when he got a bit off-key or stumbled over a line. After a winter with naught but dice games and the blacksmith’s daughter for entertainment, they cheered him as if he were the best bard at the King’s court. They made him sing until he was hoarse, that night, and let him stop only reluctantly then. Only Maddyn and Otho knew, of course, that the hall was also filled with Wildfolk, listening as intently as the men.

That night, Maddyn lay awake for a long while and listened to the familiar sound of other men snoring close by in the darkness of a barracks. He was back in a warband, back in his old life so firmly that he wondered if he’d dreamt those enchanted months in Brin Toraedic. The winter behind him seemed like a lost paradise, when he’d had good company and a woman of his own, when he’d seen a glimpse of a wider, freer world of peace and dweomer – a little glimpse only, then the door had been slammed in his face. He was back in the war, a dishonoured rider whose one goal in life was to earn the respect of other dishonoured men. At least Belyan was going to have his baby back in Cantrae, a small life who would outlive him and who would be better off as a farmer than his father would be as a warrior. Thinking about the babe he could fall asleep at last, smiling to himself.

On the day that Maddyn left Brin Toraedic, Nevyn spent a good many hours shutting up the caves for the summer and loading herbs and medicines into the canvas mule-packs. He had a journey of over nine hundred miles ahead of him, with stops along the way that were crucial to the success of his long-range plans. If he were to succeed in making a dweomer king to bring peace to the country, he would need help from powerful friends, particularly among the priesthoods. He would also need to find a man of royal blood worthy of his plans. And that, or so he told himself, might well be the most difficult part of the work.

The first week of his journey was easy. Although the Cantrae roads were full of warbands, mustering to begin the ride to Dun Deverry for the summer’s fighting, no one bothered him, seemingly only a shabby old herbman with his ambling mule, his patched brown cloak, and the white hair that the local riders respected as a sign of his great age. He followed the Canaver down to its joining with the River Nerr near the town of Muir, a place that held memories some two hundred years old. As he always did when he passed through Muir, he went into the last patch of wild forest – now the hunting preserve of the Southern Boar clan. In the midst of a stand of old oaks was an ancient, mossy cairn that marked the grave of Brangwen of the Falcon, the woman he had loved, wronged, and lost so many years ago. He always felt somewhat of a fool for making this pilgrimage – her body was long decayed, and her soul had been reborn several times since that miserable day when he’d dug this grave and helped pile up these rocks. Yet the site meant something to him still, if for no other reason than because it was the place where he’d sworn the rash vow that was the cause of his unnaturally long life.

Out of respect for a grave, even though they could have no idea of whose it was, the Boar’s gamekeepers had left the cairn undisturbed. Nevyn was pleased to see that someone had even tended it by replacing a few fallen stones and pulling the weeds away from its base. It was a small act of decency in a world where decency was in danger of vanishing. For some time he sat on the ground and watched the dappled forest light playing on the cairn while he wondered when he would find Brangwen’s soul again. His meditation brought him a small insight: she was reborn, but still a child. Eventually, he was sure, in some way Maddyn would lead him to her. In life after life, his Wyrd had been linked to hers, and, indeed, in his last life, he had followed her to the death, binding a chain of Wyrd tight around them both.

After he left Muir, Nevyn rode west to Dun Deverry for a first-hand look at the man who claimed to be King in the Holy City. On a hot spring day, when the sun lay as thick as the dust in the road, he came to the shores of the Gwerconydd, the vast lake formed by the confluence of three rivers, and let his horse and mule rest for a moment by the reedy shore. He was joined by a pair of young priests of Bel, shaven-headed and dressed in linen tunics, who were also travelling to the Holy City. After a pleasant chat, they all decided to ride in together.

‘And who’s the high priest these days?’ Nevyn asked. ‘I’ve been living up in Cantrae, so I’m badly out of touch.’

‘His Holiness, Gwergovyn,’ said the elder of the pair.

‘I see.’ Nevyn’s heart sank. He remembered Gwergovyn all too well as a spiritual ferret of a man. ‘And tell me somewhat else. I’ve heard that the Boars of Cantrae are the men to watch in court circles.’

Even though they were all alone on the open road, the young priest lowered his voice when he answered.

‘They are, truly, and there are plenty who grumble about it, too. I know His Holiness thinks rather sourly of the men of the Boar.’

At length they came to the city, which rose high on its four hills behind massive double rings of stone walls, ramparted and towered. The wooden gates, carved with a wyvern rampant, were bound with iron, and guards in thickly embroidered shirts stood to either side. Yet as soon as Nevyn went inside, the impression of splendour vanished. Once a prosperous city had filled these walls; now house after house stood abandoned, with weed-choked yards and empty windows, the thatch blowing rotten in dirty streets. Much of the city lay in outright ruin, heaps of stone among rotting, charred timbers. It had been taken by siege so many times in the last hundred years, then taken back by the sword, that apparently no one had the strength, the coin, or the hope to rebuild. In the centre of the city, around and between two main hills, lived what was left of the population, scarcely more than in King Bran’s time. Warriors walked the streets and shoved the townsfolk aside whenever they met. It seemed to Nevyn that every man he saw was a rider for one lord or another, and every woman either lived in fear of them or had surrendered to the inevitable and turned whore to please them.

The first inn he found was tiny, dirty, and ramshackle, little more than a big house divided into a tavernroom and a few chambers, but he lodged there because he liked the innkeep, Draudd, a slender old man with hair as white as Nevyn’s and a smile that showed an almost superhuman ability to keep a sense of humour in the midst of ruin. When he found out that Nevyn was an herbman, Draudd insisted on taking payment for his lodging in trade.

‘Well, after all, I’m as old as you are, so I’ll easily equal the cost in your herbs. Why give me coins only to have me give them right back?’

‘True spoken. Ah, old age! Here I’ve studied the human body all my life, but I swear old age has put pains in joints I never knew existed.’

Nevyn spent that first afternoon in the tavern, dispensing herbs for Draudd’s collection of ailments and hearing in return all the local gossip, which meant royal gossip. In Dun Deverry even the poorest person knew what there was to know about the goings-on at court. Gossip was their bard, and the royalty their only source of pride. Draudd was a particularly rich source, because his youngest daughter, now a woman in her forties, worked in the palace kitchens, where she had plenty of opportunities to overhear the noble-born servitors like the chamberlain and steward at their gossip. From what Draudd repeated that day, the Boars were so firmly in control of the King that it was something of a scandal. Everyone said that Tibryn, the Boar of Cantrae, was close to being the real king himself.

‘And now with the King so ill, our poor liege, and his wife so young, and Tibryn a widower and all …’ Draudd paused for dramatic effect. ‘Well! Can’t you imagine what we folk are wondering?’

‘Indeed I can. But would the priests allow the King’s widow to marry?’

Draudd rubbed his thumb and forefinger together like a merchant gloating over a coin.

‘Ah, by the hells!’ Nevyn snarled. ‘Has it got as bad as all that?’

‘There’s naught left but coin to bribe the priests with. They’ve already got every land grant and legal concession they want.’

At that point Nevyn decided that meeting with Gwergovyn – if indeed he could even get in to see him – was a waste of time.

‘But what ails the King? He’s still a young man.’

‘He took a bad wound in the fighting last summer. I happened to be out on the royal road when they brought him home. I’d been buying eggs at the market when I heard the bustle and the horns coming. And I saw the King, lying in a litter, and he was as pale as snow, he was. But he lived, when here we all thought they’d be putting his little lad on the throne come winter. But he never did heal up right. My daughter tells me that he has to have special food, like. All soft things, and none of them Bardek spices, neither. So they boil the meat soft, and pulp apples and suchlike.’

Nevyn was completely puzzled: the special diet made no sense at all for a man who by all accounts had been wounded in the chest. He began to wonder if someone were deliberately keeping the King weak, perhaps to gain the good favour of Tibryn of the Boar.

The best way to find out, of course, was to talk to the King’s physicians. On the morrow he took his laden mule up to the palace, which lay on the northern hill. Ring after ring of defensive walls, some stone, some earthworks, marched up the slope and cut the hill into defensible slices. At every gate, in every wall, guards stopped Nevyn and asked him his business, but they always let a man with healing herbs to sell pass on through. Finally, at the top, behind one last ring, stood the palace and all its outbuildings and servant quarters. Like a stork among chickens, a six-storey broch, ringed by four lower half-brochs, rose in the centre. If the outer defences fell, the attackers would have to fight their way through a warren of corridors and rooms to get at the King himself. In all the years of war, the palace had never fallen to force, only to starvation.

The last guard called a servant lad, who ran off to the royal infirmary with the news that a herbman waited outside. After a wait of some five minutes, he ran back and led Nevyn to a big round stone building behind the broch complex. There they were met by a burly man with dark eyes that glared under bushy brows as if their owner were in a state of constant fury, but when he introduced himself as Grodyn, the head chirurgeon, he was soft-spoken enough.

‘A herbman’s always welcome. Come spread out your wares, good sir. That table by the window would be best, I think, right in the light and fresh air.’

While Nevyn laid out packets of dried herbs, tree-barks, and sliced dried roots, Grodyn fetched his apprentice, Caudyr, a sandy-haired young man with narrow blue eyes and a jaw so sharply modelled it looked as if it could cut cheese. He also had a club foot, which gave him the rolling walk of a sailor. Between them the two chirurgeons sorted through his wares and for starters set aside his entire stock of valerian, elecampe, and comfrey root.

‘I don’t suppose you ever get down to the sea-coast,’ Grodyn said in a carefully casual tone of voice.

‘Well, this summer I’m thinking of trying to slip through the battle-lines. Usually the armies don’t much care about one old man. Is there somewhat you need from the sea?’

‘Red kelp, if you can get it, and some sea-moss.’

‘They work wonders to soothe an ulcerated stomach or bad bowels.’ Nevyn hesitated briefly. ‘Here, I’ve heard rumours about this peculiar so-called wound of our liege the King.’

‘So-called?’ Grodyn paid busy attention to the packet of beech-bark in his hand.

‘A wound in the chest that requires him to eat only soft food.’

Grodyn looked up with a twisted little smile.

‘It was poison, of course. The wound healed splendidly. While he was still weak, someone put poison into his mead. We saved him after a long fight of it, but his stomach is ulcerated and bleeding, just as you guessed, and there’s blood in his stool, too. But we’re trying to keep the news from the common people.’

‘Oh, I won’t go bruiting it about, I assure you. Do you have any idea of what this poison was?’

‘None. Now here, you know herbs. What do you think this might be? When he vomited, there was a sweetish smell hanging about the basin, rather like roses mixed with vinegar. It was grotesque to find a poison that smelled of perfume, but the strangest thing was this: the King’s page had tasted the mead and suffered not the slightest ill-effect. Yet I know it was in the mead, because the dregs in the goblet had an odd, rosy colour.’

Nevyn thought for a while, running over the long chains of lore in his memory.

‘Well,’ he said at last. ‘I can’t name the herbs out, but I’ll wager they came originally from Bardek. I’ve heard that poisoners there often use two different evil essences, each harmless in themselves. The page at table doubtless got a dose of the first one when he tasted the King’s mead, and the page of the chamber got the other. The King, alas, got both, and they combined into venom in his stomach.’

As he nodded his understanding, Grodyn looked half-sick with such an honest rage that Nevyn mentally acquitted him of any part in the crime. Caudyr too looked deeply troubled.

‘I’ve made special studies of the old herbals we have,’ the young chirurgeon said, ‘and never found this beastly poison. If it came from Bardek, that would explain it.’

‘So it would,’ Nevyn said. ‘Well, good sirs, I’ll do my best to get you the red kelp and what other emollients I can, but it’ll be autumn before I return. Will our liege live that long?’