По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

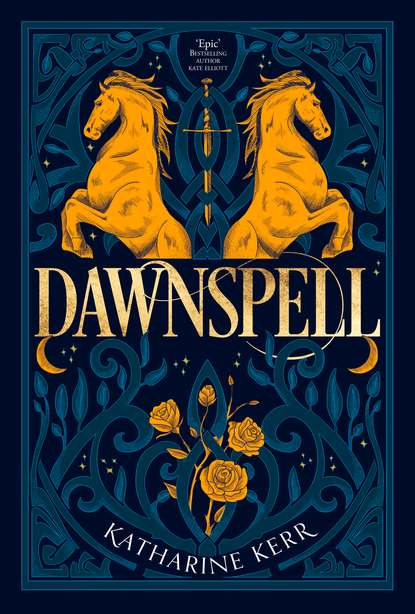

Dawnspell

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Gods! You’ve always had the luck, haven’t you?’

Maddyn merely shrugged and stoppered up the skin tight. For a moment they merely sat there in an uncomfortable silence and watched the fat grey ducks grubbing at the edge of the pond.

‘You hold your tongue cursed well for a bard,’ Aethan said abruptly. ‘Aren’t you going to ask me about my shame?’

‘Say what you want and not a word more.’

Aethan considered, staring out at the far flat horizon.

‘Ah horseshit,’ he said at last. ‘It’s a tale fit for a bard to know, in a way. Do you remember our gwerbret’s sister, the Lady Merodda?’

‘Oh, and how could any man with blood in his veins forget her?’

‘He’d best try.’ Aethan’s voice turned hard and cold. ‘Her husband was killed in battle last summer, and so she came back to her brother in Dun Cantrae. And the captain made me her escort, to ride behind her whenever she went out.’ He was quiet, his mouth working, for a good couple of minutes. ‘And she took a fancy to me. Ah, by the black ass of the Lord of Hell, I should have said her nay – I blasted well knew it, even then – but ye gods, Maddo, I’m only made of flesh and blood, not steel, and she knows how to get what she wants from a man. I swear to you, I never would have said a word to her if she hadn’t spoken to me first.’

‘I believe you. You’ve never been a fool.’

‘Not before this winter, at least. I felt like I was ensorcelled. I’ve never loved a woman that way before, and cursed if I ever will again. I wanted her to ride off with me. Like a misbegotten horseshit fool, I thought she loved me enough to do it. But oh, it didn’t suit her ladyship, not by half.’ Again the long, pain-filled pause. ‘So she let it slip to her brother what had been happening between us, but oh, she was the innocent one, she was. And when His Grace took all the skin off my back three days ago, she was out in the ward to watch.’

Aethan dropped his face into his hands and wept like a child. For a moment Maddyn sat there frozen; then he reached out a timid hand and laid it on Aethan’s shoulder until at last he fell silent and wiped his face roughly on his sleeve.

‘Maybe I shouldn’t be too hard on her.’ Aethan’s voice was a flat, dead whisper. ‘She did keep her brother from killing me.’ He stood up, and it was painful to watch him wince as he hauled himself to his feet. ‘I’ve rested enough. Let’s ride, Maddo. The farther I get from Cantrae the happier I’ll be.’

For four days Maddyn and Aethan rode west, asking cautious questions of the various farmers and pedlars that they met about the local lords and their warbands. Even though they sometimes heard of a man who might be desperate enough to take them in without asking questions, each time they decided that they were still too close to Cantrae to risk petitioning him. They realized, however, that they would have to find some place soon, because all around them the noble-born were beginning to muster their men for the summer’s fighting. With troops moving along the roads they were in a dangerous position. Maddyn had no desire to escape being hanged for an outlaw only to end up in a rope as a supposed spy.

Since Aethan’s back was far from healed, they rode slowly, stopping often to rest, either beside the road or in village taverns. They had, at least, no need to worry about coin; not only did Maddyn have Nevyn’s generous pouch, but Aethan’s old captain had managed to slip him money along with his gear when he’d been kicked out of Dun Cantrae. Apparently Maddyn wasn’t alone in thinking the gwerbret’s sentence harsh. During this slow progress west, Maddyn had plenty of time to watch and worry over his old friend. Since always before, Aethan had watched over him – he was, after all, some ten years Maddyn’s elder – Maddyn was deeply troubled to realize that Aethan needed him the way a child needs his father. The gwerbret might have spared his life, but he’d broken him all the same, this man who’d served him faithfully for over twenty years, by half beating him to death like a rat caught in a stable.

Always before Aethan had had an easy way with command, making decisions, giving orders, and all in a way that made his fellows glad to follow them. Now he did whatever Maddyn said without even a mild suggestion that they might do otherwise. Before, too, he’d been a talkative man, always ready with a tale or a jest if he didn’t have serious news to pass along. Now he rode wrapped in a black hiraedd; at times he didn’t even answer when Maddyn asked him a direct question. For all that it ached Maddyn’s heart, he could think of nothing to do to better things. Often he wished that he could talk with Nevyn and get his advice, but Nevyn was far away, and he doubted if he’d ever see the old man again, no matter how much he wanted to.

Eventually they reached the great river, the Camyn Yraen, an ‘iron road’ even then, because all the rich ore from Cerrgonney came down it in barges, and the town of Gaddmyr, at that time only a large village with a wooden palisade around it for want of walls. Just inside the gate they found a tavern of sorts, basically the tavernman’s house, with half the round ground floor set off by a wickerwork partition to hold a couple of tables and some alebarrels in the curve of the wall. For a couple of coppers the man brought them a chunk of cheese and a loaf of bread to go with their ale, then left them strictly alone. Maddyn noticed that none of the villagers were bothering to come to the tavern with them in it, and he remarked as much to Aethan.

‘For all they know, we’re a couple of bandits. Ah, by the hells, Maddo, we can’t go wandering the roads like this, or we might well end up robbing travellers, at that. What are we going to do?’

‘Cursed if I know. But I’ve been thinking a bit. There’s those free troops you hear about. Maybe we’d be better off joining one of them than worrying about an honourable place in a warband.’

‘What?’ For a moment some of the old life came back to Aethan’s eyes. ‘Are you daft? Fight for coin, not honour? Ye gods, I’ve heard of some of those troops switching sides practically in the middle of a battle if someone offered them better pay. Mercenaries! They’re naught but a lot of dishonoured scum!’

Maddyn merely looked at him. With a long sigh Aethan rubbed his face with both hands.

‘And so are we. That’s what you mean, isn’t it, Maddo? Well, you’re right enough. All the gods know that the captain of a free troop won’t be in any position to sneer at the scars on my back.’

‘True spoken. And we’ll have to try to find one that’s fighting for Cerrmor or Eldidd, too. Neither of us can risk having some Cantrae man seeing us in camp.’

‘Ah, horseshit and a pile of it! Do you know what that means? What are we going to end up doing? Riding a charge against the gwerbret and all my old band some day?’

Maddyn had never allowed himself to frame that thought before, that some day his life might depend on his killing a man who’d once been his ally and friend. Aethan picked up his dagger and stabbed it viciously into the table.

‘Here!’ The tavernman came running. ‘No need to be breaking up the furniture, lads!’

Aethan looked up so grimly that Maddyn caught his arm before he could take out his rage on this innocent villager. The tavernman stepped back, swallowing hard.

‘I’ll give you an extra copper to pay for the damage,’ Maddyn said. ‘My friend’s in a black mood today.’

‘He can go about having it in some other place than mine.’

‘Well and good, then. We’ve finished your piss-poor excuse for ale, anyway.’

They’d just reached the door when the tavernman hailed them again. Although Aethan ignored him and walked out, Maddyn paused as the taverner came scurrying over.

‘I know about one of them troops you and your friend was talking about.’

Maddyn got out a couple of coppers and jingled them in his hand. The taverner gave him a gap-toothed, garlicscented grin.

‘They wintered not far from here, they did. They rode in every now and then to buy food, and we was fair terrified at first, thinking they were going to steal whatever they wanted, but they paid good coin. I’ll say that for them, for all that they was an arrogant lot, strutting around like lords.’

‘Now that’s luck!’

‘Well, now, they might have moved on by now. Haven’t seen them in days, and here’s the blacksmith’s daughter with her belly swelling up, and even if they did come back, she wouldn’t even know which of the lads it was. The little slut, spreading her legs for any of them that asked her!’

‘Indeed? And where were they quartered?’

‘They wouldn’t be telling the likes of us that, but I’ll wager I can guess well enough. Just to the north of here, oh, about ten miles, I’d say, is a stretch of forest. It used to be the tieryn’s hunting preserve, but then, twenty-odd years ago it was now, the old tieryn and all his male kin got themselves killed off in a blood feud, and with the wars so bad and all, there was no one else to take the demesne. So now the forest’s all overgrown and thick, like, but I wager that the old tieryn’s hunting-lodge still stands in there some place.’

Maddyn handed over the coppers and took out two more.

‘I don’t suppose some of the lads in the village know where this lodge is?’ He held up the coins. ‘It seems likely that some of the young ones might have poked around in there, just out of curiosity, like.’

‘Not on your life, and I’m not saying that to get more coin out of you, neither. It’s a dangerous place, that stretch of trees. Haunted, they say, and full of evil spirits as well, most like, and then there’s the wild men.’

‘The what?’

‘Well, I suppose that by rights I shouldn’t call them wild, poor bastards, because all the gods can bear witness that I’d have done the same as them if I had to.’ He leaned closer, all conspiratorial. ‘You don’t look like the sort of fellow who’ll be running to our lord with the news, but the folk who live in the forest are bondsmen. Or I should say, they was, a while back. Their lord got killed, and so they took themselves off to live free, and I can’t say as I’ll be blaming them for it, neither.’

‘Nor more can I. Your wild men are safe enough from me, but I take it they’re not above robbing a traveller if they can.’

‘I think they feels it’s owing to them, like, after all the hard work they put in.’

Maddyn gave him the extra coppers anyway, then went out to join Aethan, who was standing by the road with the horses’ reins in hand.

‘Done gossiping, are you?’

‘Here, Aethan, the taverner had some news to give us, and it just might be worth following down. There might be a free troop up in the woods to the north of us.’

Aethan stared down at the reins in his hand and rubbed them with weary fingers.

‘Ah, horseshit!’ he said at last. ‘We might as well look them over, then.’

When they left the village, they rode north, following the river. Although Aethan was well on the mend by then, his back still ached him, and they rested often. At their pace it was close to sunset when they reached the forest, looming dark and tangled on the far side of a wild meadowland. At its edge a massive marker stone still stood, doubtless proclaiming the trees the property of the long-dead clan that once had owned them.