По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

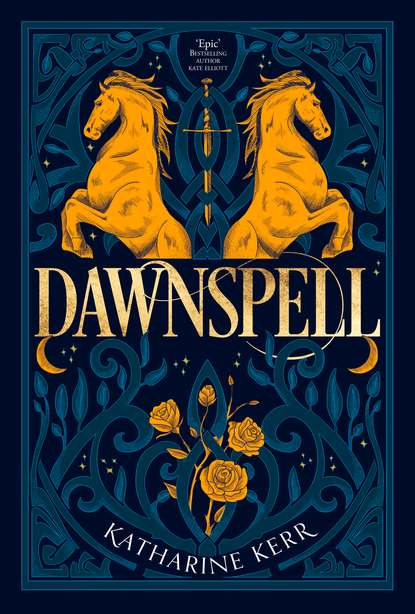

Dawnspell

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘To tell you the truth, I’m afraid to.’

The old man laughed under his breath.

‘Well, I’ll answer anyway, questions or no. Those were what men call the Wildfolk. They’re like ill-trained children or puppies, all curiosity, no sense or manners. Unfortunately, they can hurt us mortal folk without even meaning to do so.’

‘I gathered that, sure enough.’ As he looked at his benefactor, Maddyn realized a truth he’d been avoiding for days now. ‘Sir, you must have dweomer.’

‘I do. How does that strike you?’

‘Like a blow. I never thought there was any such thing outside my own ballads and tales.’

‘Most men would consider me a bard’s fancy, truly, but my craft is real enough.’

Maddyn stared, wondering how Nevyn could look so cursed ordinary, until the old man turned away with a good-humoured laugh and began rummaging in his saddlebags.

‘I brought you a bit of roast meat for your supper, lad. You need it to make back the blood you lost, and the villager I visited had some to spare to pay for my herbs.’

‘My thanks. Uh, when do you think I’ll be well enough to ride out?’

‘Oho! The spirits have you on the run, do they?’

‘Well, not to be ungrateful or suchlike, good sir’ Maddyn felt himself blush ‘but I … uh … well …’

Nevyn laughed again.

‘No need to be ashamed, lad. Now as to the wound, it’ll be a good while yet before you’re fit. You rode right up to the gates of the Otherlands, and it always takes a man a long time to ride back again.’

From that day on, the Wildfolk grew bolder around Maddyn, the way that hounds will slink out from under the table when they realize that their master’s guest is fond of dogs. Every time Maddyn picked up his harp, he was aware of their presence – a liveliness in the room, a small scuffle of half-heard noise, a light touch on his arm or hair, a breath of wind as something flew by. Whenever they pinched or mobbed him, he would simply threaten to stop singing, a threat that always made them behave themselves. Once, when he was struggling to light a fire with damp tinder, he felt them gather beside him. As he struck a spark from his steel, the Wildfolk blew it into a proper flame. When he thanked them automatically, he realized that he was beginning to take spirits for granted. As for Nevyn himself, although Maddyn studied the old man for traces of strange powers and stranger lore, he never saw any, except, of course, that spirits obeyed him.

Maddyn also spent a lot of time thinking over his future. Since he was a member of an outlawed warband, he would hang if Tieryn Devyr ever got his hands on him. His one chance of an honourable life was slim indeed. If he rode down to Cantrae without the tieryn catching him, and then threw himself upon the gwerbret’s mercy, he might be pardoned simply because he was something of a bard and thus under special protection in the laws. Unfortunately, the pardon was unlikely, because it would depend on his liege’s whim, and Gwerbret Tibryn of the Boar was a harsh man. His clan, the Boars of the North, was related to the southern Boars of Muir, who had wheedled the gwerbretrhyn out of the King in Dun Deverry some fifty years before. Between them, the conjoint Boar clans ruled a vast stretch of the northern kingdom and were said to be the real power behind a puppet king in the Holy City. It was unlikely that Tibryn would bother to show mercy to a half-trained bard when that mercy would make one of his loyal tieryns grumble. Maddyn decided that since he and the spirits had worked out their accommodation, he would leave the gwerbret’s mercy alone and stay in Brin Toraedic until spring.

The next time that Nevyn rode to the village, Maddyn decided to ride a-ways with him to exercise both himself and his horse. The day was clear and cold, with the smell of snow in the air and a rimy frost lying on the brown stubbled fields. When he realized that it was nearly Samaen, Maddyn was shocked at the swift flowing of time outside the hill, which seemed to have a different flow of its own. Finally they came to the village, a handful of round, thatched houses scattered among white birches along the banks of a stream.

‘I’d best wait for you by the road,’ Maddyn said. ‘One of the tieryn’s men might ride into the village for some reason.’

‘I don’t want you sitting out in this cold. I’ll take you over to a farm near here. These people are friends of mine, and they’ll shelter you without awkward questions.’

They followed a lane across brown pastureland until they came to the farmstead, a scatter of round buildings inside a circular, packed-earth wall. At the back of the big house was a cow-barn, storage sheds, and a pen for grey and white goats. In the muddy yard, chickens pecked round the front door of the house. Shooing the hens away, a stout man with greying hair came out to greet them.

‘Morrow, my lord. What can I do for you this morning?’

‘Oh, just keep a friend of mine warm, good Bannyc. He’s been very ill, as I’m sure his white face is telling you, and he needs to rest while I’m in the village.’

‘We can spare him room at the hearth. Ye gods, lad, you’re pale as the hoar frost, truly.’

Bannyc ushered Maddyn into the wedge-shaped main room, which served as kitchen and hall both. In front of a big hearth, where logs blazed in a most welcome way, stood two tables and three high-backed benches, a prosperous amount of furniture for those parts. Clean straw covered the floor, and the walls were freshly whitewashed. From the ceiling hung strings of onions and garlic, nets of drying turnips and apples, and a couple of enormous hams. On the hearthstone a young woman was sitting cross-legged and mending a pair of brigga.

‘Who’s this, Da?’ she said.

‘A friend of Nevyn’s.’

Hastily she scrambled up and dropped Maddyn a curtsey. She was very pretty, with raven-black hair and dark, calm eyes. Maddyn bowed to her in return.

‘You’ll forgive me for imposing on you,’ Maddyn said. ‘I haven’t been well, and I need a bit of a rest.’

‘Any friend of Nevyn’s is always welcome here,’ she said. ‘Sit down, and I’ll get you some ale.’

Maddyn took off his cloak, then sat down on the hearthstone as close to the fire as he could get without singeing his shirt. Announcing that he had to get back to the cows, Bannyc strolled outside. The woman handed Maddyn a tankard of dark ale, then sat down near him and picked up her mending again.

‘My thanks.’ Maddyn saluted her with the ale. ‘My name’s Maddyn of … uh, well, just Maddyn will do.’

‘Mine’s Belyan. Have you known Nevyn long?’

‘Oh, not truly.’

Belyan gave him an oddly awestruck smile and began sewing. Maddyn sipped his ale and watched her slender fingers work deftly on the rough wool of a pair of brigga, Bannyc’s, by the large size of them. He was surprised at how good it felt to be sitting warm and alive in the presence of a pretty woman. Every now and then, Belyan hesitantly looked his way, as if she were trying to think of something to say.

‘Well, my lord,’ she said at last. ‘Will you be staying long with our Nevyn?’

‘I don’t truly know, but here, what makes you call me lord? I’m as common-born as you are.’

‘Well – but a friend of Nevyn’s.’

At that Maddyn realized that she knew perfectly well that the old man was dweomer.

‘Now here, what do you think I am?’ Maddyn had the uneasy feeling that it was very dangerous to pretend to dweomer you didn’t have. ‘I’m only a rider without a warband. Nevyn was good enough to save my life when he found me wounded, that’s all. But here, don’t tell anyone about me, will you? I’m an outlawed man.’

‘I’ll forget your name the minute you ride on.’

‘My humble thanks, and my apologies. I don’t even deserve to be drinking your ale.’

‘Oh hold your tongue! What do I care about these rotten wars?’

When he looked at her, he found her angry, her mouth set hard in a bitter twist.

‘I don’t care the fart of a two-copper piglet,’ she went on. ‘All it’s ever brought to me and mine is trouble. They take our horses and raise our taxes and ride through our grain, and all in the name of glory and the one true King, or so they call him, when everyone with wits in his head knows there’s two kings now, and why should I care, truly, as long as they don’t both come here a-bothering us. If you’re one man who won’t die in this war, then I say good for you.’

‘Ye gods. Well, truly, I never thought of it that way before.’

‘No doubt, since you were a rider once.’

‘Here, I’m not exactly a deserter or suchlike.’

She merely shrugged and went back to her sewing. Maddyn wondered why a woman of her age, twenty-two or so, was living in her father’s house. Had she lost a betrothed in the wars? The question was answered for him in a moment when two small lads, about six and four, came running into the room and calling her Mam. They were fighting over a copper they’d found in the road and came to her to settle it. Belyan gave them each a kiss and told them they’d have to give the copper to their gran, then sent them back outside.

‘So you’re married, are you?’ Maddyn said.

‘I was once. Their father drowned in the river two winters ago. He was setting a fish-trap, but the ice turned out to be too thin.’