По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

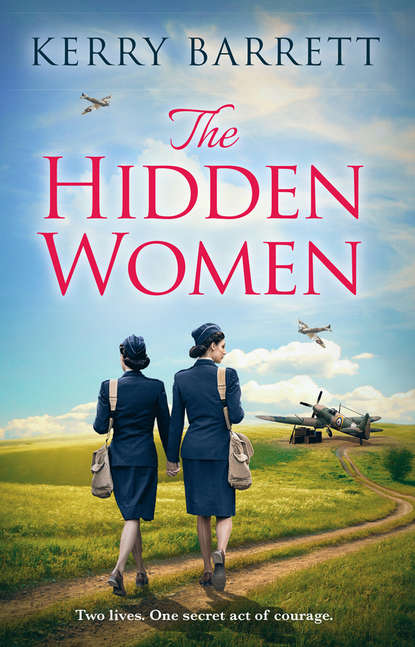

The Hidden Women: An inspirational novel of sisterhood and strength

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Morning, Lil,’ Marcus the postman called. ‘Mind how you go.’

I ignored him, concentrating on keeping my legs going round. I had an ache in my stomach and my limbs felt heavy and hard to control.

‘By lunchtime it’ll be over,’ I whispered to myself over and over as I cycled. ‘By lunchtime it’ll be over.’

I could see the house up ahead, squatting at the end of the village like a slug, and growing bigger as I approached. I slid off my bicycle and chained it to the fence, and then, dragging my heels, walked up the path to the front door. Before I could knock, it opened. My piano teacher’s wife stood there. She was dressed to go out, wearing her hat and holding her gloves in one hand and her handbag in the other. I wanted to cry.

‘Lilian,’ she said, beaming at me ‘How nice to see you. He’s in the music room – go on through.’

I forced a smile. ‘Thank you, Mrs Mayhew,’ I muttered, slinking past her. She was so pretty and fresh-looking in her summer dress. I felt her eyes on me as I went and wondered if she knew. If she could tell. I felt dirty. No, not dirty. Filthy.

At the music room door, I paused. Then I lifted my hand and knocked.

‘Come,’ said Mr Mayhew. Taking a breath, I went.

Mr Mayhew was sitting at the piano, making pencil notes on some sheet music that was on the stand.

‘Ah, Lilian,’ he said. ‘You’re late.’

He turned round on the stool and gave me a dazzling smile. My breath caught in my throat. Always when I wasn’t with him, he became a monster in my head. Then, when I saw him again – saw his dark, swarthy good looks and his broad shoulders – I wondered what I had been worrying about.

‘Come and sit,’ he said, shifting over on the padded stool. ‘Let’s play something fun to get warmed up.’

I put down my music case and settled myself next to him. I felt the warmth of his body as his thigh brushed mine when I sat, but I couldn’t move away because the stool was too small.

Mr Mayhew – I couldn’t call him Ian, even though he’d told me to – moved a sheet of music to the front of the bundle on the stand. It was a Bach piece that had been one of my favourites, long ago when I was still a child.

He turned to me, his face just inches from mine. I smelled coffee on his breath and tried not to recoil as nausea overwhelmed me.

‘Ready?’ he said.

I nodded, putting my hands on to the keys.

‘Two, three, four …’ he counted us in.

I knew the music by heart, so as I played I shut my eyes and imagined I was anywhere but in this stuffy room, with Mr Mayhew’s body heat spreading through my thin cotton frock.

At the end of the piece, Mr Mayhew stood up and I felt myself relax. Slightly.

‘Good,’ he said, strolling over to the window and gazing out into the garden. ‘Now let’s go through your examination pieces. Start with the Brahms.’

I relaxed a bit more, realising he wanted to concentrate on music today.

‘Could you open a window, please?’ I asked. ‘It’s very warm.’

He nodded and pushed the sash upwards. ‘Are you feeling well?’ he asked me, his brow furrowed in concern. ‘You’re very pale.’

I swallowed. ‘I’m fine,’ I said. ‘It’s just the heat.’

Mr Mayhew came over to where I sat and stood behind me. Gently, he reached out and stroked the back of my neck.

‘Lilian,’ he said gruffly. ‘Is something wrong?’

I froze. My stomach was squirming and I wasn’t sure I could put how I was feeling into words. How could I tell him I’d wanted his approval for months, so badly that I almost felt a physical ache when I played a wrong note. That when he smiled at me my heart sang with the most beautiful music. That when he told me I was special to him, I wanted to throw myself into his arms and stay there forever. And yet, as spring had blossomed into early summer, and he had kissed me for the first time, I’d gone home feeling confused and guilty. When, just a week later, he had put his hand up my skirt while I played, his fingers probing and hurting, I’d gasped in fear and he’d nodded.

‘Like that?’ he said, his voice thick. ‘I thought you would. I knew what you wanted from the day you walked in here.’

I’d stayed still, not understanding what he was doing. Not wanting to upset him by asking him to stop. Because I had wanted this. Hadn’t I?

Now, after our lessons he would kiss me, and touch me – and make me touch him too. I didn’t know how to say no. Because I’d started this, hadn’t I? And sometimes he came to school to meet me at the gate and give me music he’d copied for me by hand – see how much cared – and we walked home the long way through the woods. And he’d take me by the hand and lower me into the soft moss below one of the trees and unbuckle his belt and …

I found that by imagining playing the piano I could pretend it wasn’t happening. And then when it was over, Mr Mayhew would always be so kind. He would brush leaves from my hair, and tell me how precious I was. I never cried until I was alone.

Now, feeling his fingers on the back of my neck, I waited for what he would do next.

‘Are you cross with me?’ he murmured. ‘Because I wanted you to play first?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I want to play.’

‘You tease me,’ he said. He trailed his fingers over my collarbone and down to my bust, and I closed my eyes.

And then the front door banged shut and he pulled away as if my faded cotton dress was prickly.

‘Ian,’ Mrs Mayhew called. ‘Ian, are you there?’

She came into the music room without knocking, which she never did. Mr Mayhew was very strict about that. Not a surprise, I supposed, given what we were often doing instead of playing piano.

Mrs Mayhew’s hat was askew and her hair was escaping from its roll. She had a streak of dust across the front of her dress and her forehead was beaded with sweat. I’d never seen her look so flustered; she was normally perfectly groomed.

‘Oh, Ian,’ she wailed. ‘Ian, have you heard the news?’

Mr Mayhew stiffened next to me. ‘He’s done it, has he?’ he said. ‘He’s bloody gone and done it?’

A tear rolled down Mrs Mayhew’s face, leaving a clean track in the grime on her cheek.

‘I ran all the way from the village,’ she said. ‘They were talking about it on the street. Mrs Armitage was sitting at the war memorial, just weeping.’

I felt sicker than I had moments before. Mrs Armitage had lost both her sons in the Great War. The war we’d been told would end all wars. The war that my own father never talked about.

‘What does this mean?’ I stammered. ‘Is it Hitler? What has he done?’

Mr Mayhew patted me on the head distractedly, his full attention on his wife.

‘He’s sent his troops into Poland,’ he said. ‘And Mr Chamberlain promised that if he did that, then …’ His voice trailed off.

‘I need to go home,’ I said. ‘I need to find Bobby.’

Mrs Mayhew looked at me for the first time. I didn’t think she’d even realised I was there before then.