По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

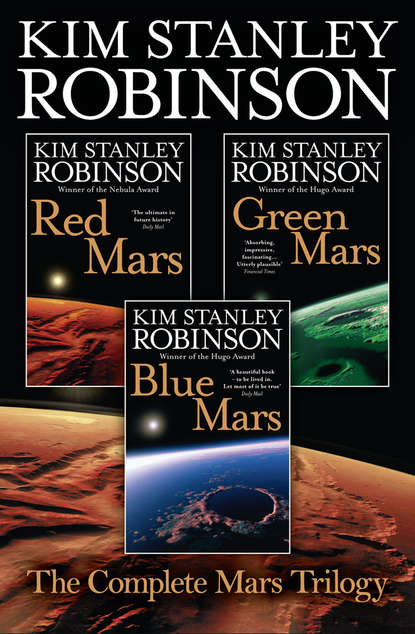

The Complete Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Dark solid mineral particles.”

Nadia snorted. “I could have told you that.”

“Not before we got here you couldn’t. It might have been fines aggregated with salts. But it’s bits of rock instead.”

“Why so dark?”

“Volcanic. On Earth sand is mostly quartz, you see, because there’s a lot of granite there. But Mars doesn’t have much granite. These grains are probably volcanic silicates. Obsidian, flint, some garnet. Beautiful, isn’t it?”

She held out a handful of sand for Nadia’s inspection. Perfectly serious, of course. Nadia peered through her faceplate at the black grit. “Beautiful,” she said.

They stood and watched the sun set. Their shadows went right out to the eastern horizon. The sky was a dark red, murky and opaque, only slighty lighter in the west over the sun. The clouds Ann had mentioned were bright yellow streaks, very high in the sky. Something in the sand caught at the light, and the dunes were distinctly purplish. The sun was a little gold button, and above it shone two evening stars: Venus, and the Earth.

“They’ve been getting closer every night lately,” Ann said softly. “The conjunction should be really brilliant.”

The sun touched the horizon, and the dune crests faded to shadow. The little button sun sank under the black line to the west. Now the sky was a maroon dome, the high clouds the pink of moss campion. Stars were popping out everywhere, and the maroon sky shifted to a vivid dark violet, an electric color that was picked up by the dune crests, so that it seemed crescents of liquid twilight lay across the black plain. Suddenly Nadia felt a breeze swirl through her nervous system, running up her spine and out into her skin; her cheeks tingled, and she could feel her spinal cord thrum. Beauty could make you shiver! It was a shock to feel such a physical response to beauty, a thrill like some kind of sex. And this beauty was so strange, so alien. Nadia had never seen it properly before, or never really felt it, she realized that now; she had been enjoying her life as if it were a Siberia made right, living in a huge analogy, understanding everything in terms of her past. But now she stood under a tall violet sky on the surface of a petrified black ocean, all new, all strange: it was absolutely impossible to compare it to anything she had seen before; and all of a sudden the past sheered away in her mind and she turned in circles like a little girl trying to make herself dizzy, without a thought in her head. Weight seeped inward from her skin, and she didn’t feel hollow anymore; on the contrary she felt extremely solid, compact, balanced. A little thinking boulder, set spinning like a top.

They glissaded down the steep face of the dune on their boot heels. At the bottom Nadia gave Ann an impulsive hug: “Oh Ann, I don’t know how to thank you for that.” Even through the tinted faceplates she could see Ann grin. A rare sight.

After that things looked different to Nadia. Oh she knew it was in herself, that it was a matter of paying attention in a new way, of looking. But the landscape conspired in this sensation, feeding her new attentiveness; because the very next day they left the black dunes, and drove on to what her companions called layered or laminate terrain. This was the region of flat sand that in winter would lie under the CO

skirt of the polar cap. Now in midsummer it lay revealed, a landscape made entirely of curvilinear patterns. They drove up broad flat washes of yellow sand that were bounded by long sinuous flat-topped plateaus; the sides of the plateaus were stepped and benched, laminated both finely and grossly, looking like wood that had been cut and polished to show a handsome grain. None of them had ever seen any land remotely like it, and they spent the mornings taking samples and borings, and hiking around in a loping Martian ballet, talking a blue streak, Nadia as excited as any of them. Ann explained to her that each winter’s frost caught a lamina on the surface. Then wind erosion had cut arroyos, and stripped away at their sides, and each stratum was stripped back farther than the one below it, so that the arroyo walls consisted of hundreds of narrow terraces. “It’s like the land is a contour map of itself,” Simon said.

They drove during the days and went out every evening in purply dusks that lasted until just before midnight. They drilled borings, and came up with cores that were gritty and icy, laminated for as far down as they could drill. One evening Nadia was climbing with Ann up a series of parallel terraces, half-listening to her explain about the precession of aphelion and perihelion, when she looked back across the arroyo and saw that it was glowing like lemons and apricots in the evening light, and that above the arroyo were pale green lenticular clouds, mimicking perfectly the terrain’s French curves. “Look!” she exclaimed.

Ann looked back and saw it, and was still. They watched the low banded clouds float overhead.

Finally a dinner call from the rovers brought them back. And walking down over the contoured terraces of sand, Nadia knew that she had changed – that, or else the planet was getting much more strange and beautiful as they traveled north. Or both.

They rolled over flat terraces of yellow sand, sand so fine and hard and clear of rocks that they could go at full speed, slowing down only to shift up or down from one bench to another. Occasionally the rounded slope between terraces gave them some trouble, and once or twice they even had to backtrack to find a way. But usually a route north could be found without difficulty.

On their fourth day in the laminate terrain, the plateau walls flanking their flat wash curved together, and they drove up the cleavage onto a higher plane; and there before them on the new horizon was a white hill, a great rounded thing, like a white Ayer’s Rock. A white hill – it was ice! A hill of ice, a hundred meters high and a kilometer wide – and when they drove around it, they saw that it continued over the horizon to the north. It was the tip of a glacier, perhaps a tongue of the polar cap itself. In the other cars they were shouting, and in the noise and confusion Nadia could only hear Phyllis, crying “Water! Water!”

Water indeed. Though they had known it was going to be there, it was still startling in the extreme to run into a whole great white hill of it, in fact the tallest hill they had seen in the entire five thousand kilometers of their voyage. It took them all that first day to get used to it: they stopped the rovers, pointed, chattered, got out to have a look, took surface samples and borings, touched it, climbed up it a ways. Like the sand around it, the ice hill was horizontally laminated, with lines of dust about a centimeter apart. Between the lines the ice was pocked and granular; in this atmospheric pressure it sublimed at almost all temperatures, leaving pitted, rotten side walls to a depth of a few centimeters; under that it was solid, and hard.

“This is a lot of water,” they all said at one point or another. Water, on the surface of Mars …

The next day the glacier hill formed their right horizon, a wall that ran on beside them for the whole day’s drive. Then it really began to seem like a lot of water, especially as over the course of the day the wall got taller, rising to a height of about three hundred meters. A kind of white mountain ridge, in fact, walling off their flat-bottomed valley on its east side. And then, over the horizon to the northwest, there appeared another white hill, the top of another ridge poking over the horizon, the base remaining beneath it. Another glacier hill, walling them in to the west, some thirty kilometers away.

So they were in Chasma Borealis, a wind-carved valley that cut north into the ice cap for some five hundred kilometers, more than half the distance to the Pole. The chasm’s floor was flat sand, hard as concrete, and often crunchy with a layer of CO

frost. The chasm’s ice walls were tall, but not vertical; they lay back at an angle less than 45°, and like the hillsides in the laminate terrain, they were terraced, the terraces ragged with wind erosion and sublimation, the two forces that over tens of thousands of years had cut the whole length of the chasm.

Rather than driving up to the head of the valley, the explorers crossed to the western wall, aiming toward a transponder that had been included in a drop of ice-mining equipment. The sand dunes mid-chasm were low and regular, and the rovers rolled over the corrugated land, up and down, up and down. Then as they crested a sand wave they spotted the drop, no more than two kilometers from the foot of the northwest ice wall: bulky lime green containers on skeletal landing modules, a strange sight in this world of whites and tans and pinks. “What an eyesore!” Ann exclaimed, but Phyllis and George were cheering.

During the long afternoon, the shadowed western iceside took on a variety of pale colors: the purest water ice was clear and bluish, but most of the hillside was a translucent ivory, copiously tinted by pink and yellow dust. Irregular patches of CO

ice were a bright pure white; the contrast between dry ice and water ice was vivid, and made it impossible to read the actual contours of the hillside. And foreshortening made it hard to tell how tall the hill really was; it seemed to go up forever, and was probably somewhere between three and five hundred meters above the floor of Borealis.

“This is a lot of water,” Nadia exclaimed.

“And there’s more underground,” Phyllis said. “Our borings show that the cap actually extends many degrees of latitude farther south than we see, buried under the layered terrain.”

“So we have more water than we’ll ever need!”

Ann pursed her mouth unhappily.

The drop of the mining equipment had determined the site of the ice mining camp: the west wall of Chasma Borealis, at longitude 41°, latitude 83° N. Deimos had just recently followed Phobos under the horizon; they wouldn’t see it again until they returned south of 82° N. The summer nights consisted of an hour’s purple twilight; the rest of the time the sun wheeled around, never more than twenty degrees above the horizon. The six of them spent long hours outside, moving the ice miner to the wall and then setting it up. The main component was a robotic tunnel borer, about the size of one of their rovers. The borer cut into the ice, and passed back cylindrical drums 1.5 meters in diameter. When they turned the borer on it made a loud, low buzz, which was louder still if they put their helmets to the ice, or even touched it with their hands. After a while white ice drums thumped into a hopper, and then a small robot forklift carried them to a distillery, which would melt the ice and separate out its considerable load of dust, then refreeze the water into one-meter cubes more suitable for packing in the holds of the rovers. Robot freight rovers would then be perfectly capable of driving to the site, loading up and returning to base on their own; and base would then have a regular water supply, larger than they could ever use. Around four or five trillion cubic kilometers in the visible polar cap, Edvard calculated, though there were a lot of guesses in the calculation.

They spent several days testing the miner and deploying an array of solar panels to power it. In the long evenings after dinner Ann would climb the ice wall, ostensibly to take more borings, although Nadia knew she just wanted away from Phyllis and Edvard and George. And naturally she wanted to climb all the way to the top, to get on the polar cap and look around, and take borings of the most recent layers of ice; and so one day when the miner had passed all the test routines, she and Nadia and Simon got up at dawn – just after two a.m. – and went out into the supercold morning air and climbed, their shadows like big spiders climbing before them. The slope of the ice was about 30°, steepening and then letting off time after time as they ascended the rough benches in the hill’s layered side.

It was seven a.m. when the slope laid back and they walked onto the surface of the polar cap. To the north was a plain of ice that extended as far as they could see, to a high horizon some thirty kilometers away. Looking back to the south they could see a great distance over the geometric swirls of the layered terrain; it was the longest view Nadia had ever had on Mars.

The ice of the plateau was layered much like the laminated sand below them, with wide bands of dirty pink contouring across cleaner stuff. The other wall of Chasma Borealis lay off to the east, looking almost vertical from their point of view, long, tall, massive: “So much water!” Nadia said again. “It’s more than we’ll ever need.”

“That depends,” Ann said absently, screwing the frame of the little borer into the ice. Her darkened faceplate turned up at Nadia: “If the terraformers have their way, this will all go like dew on a hot morning. Into the air to make pretty clouds.”

“Would that be so bad?” Nadia asked.

Ann stared at her. Through the tinted faceplate her eyes looked like ballbearings.

That night at dinner she said, “We really ought to make a run up to the pole.”

Phyllis shook her head. “We don’t have the food or air.”

“Call for a drop.”

Edvard shook his head. “The polar cap is cut by valleys almost as deep as Borealis!”

“Not so,” Ann said. “You could drive straight to it. The swirl valleys look dramatic from space, but that’s because of the difference in albedo between the water and the CO

. The actual slopes are never more than 6° off the horizontal. It’s just more layered terrain, really.”

George said, “But what about getting onto the cap in the first place?”

“We drive around to one of the tongues of ice that drop to the sand. They’re like ramps up to the central massif, and once there, we drive right to the pole!”

“There’s no reason to go,” Phyllis said. “It’ll just be more of what we see here. And it means more exposure to radiation.”

“And,” George added, “we could use what food and air we do have to check out some of the sites we passed on the way up here.”

So that was their point. Ann scowled. “I’m the head of the geological survey,” she said sharply. Which may have been true, but she was a horrible politician, especially compared to Phyllis, who had any number of friends in Houston and Washington.

“But there’s no geological reason to go to the pole,” Phyllis said now with a smile. “It’ll be the same ice as here. You just want to go.”

“Well?” Ann said. “Say I do! There are still scientific questions to be answered up there. Is the ice the same composition, how much dust – everywhere we go up here we collect valuable data.”

“But we’re up here to get water. We’re not up here to fool around.”