По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

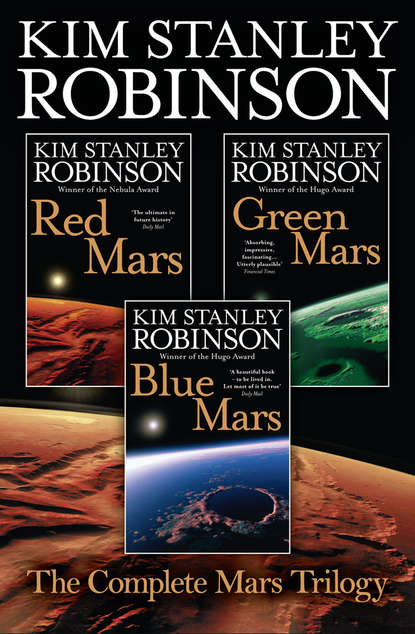

The Complete Mars Trilogy: Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“It’s not fooling around!” Ann snapped. “We obtain water to allow us to explore, we don’t explore just to obtain water! You’ve got it backwards! I can’t believe how many people in this colony do that!”

Nadia said, “Let’s see what they say at base. They might want us to help with something there, or they might not be able to send a drop, you never know.”

Ann groaned. “We’ll end up asking permission from the UN, I swear.”

She was right. Frank and Maya didn’t like the idea, John was interested but noncommittal. Arkady supported it when he heard of it, and declared he would send a supply drop from Phobos if necessary, which given its orbit was impractical at best. But at that point Maya called mission control in Houston and Baikonur, and the argument rippled outward. Hastings opposed the plan; but Baikonur, and a lot of the scientific community, liked it.

Finally Ann got on the phone, her voice very curt and arrogant, though she looked scared: “I’m the geological head here, and I say it needs to be done. There won’t be any better opportunity to get onsite data on the original condition of the polar cap. It’s a delicate system, and any change in the atmosphere is going to impact it heavily. And you’ve got plans to do that, right? Sax, are you still working on those windmill heaters?”

Sax had not been part of the discussion and he had to be called to the phone. “Sure,” he said when the question was repeated. He and Hiroko had come up with the idea of manufacturing small windmills, to be dropped from dirigibles all over the planet. The constant westerlies would spin the windmills, and the spin would be converted to heat in coils in the base of the mills, and this heat would simply be released into the atmosphere. Sax had already designed a robotic factory to manufacture the windmills; he hoped to make them by the thousands. Vlad pointed out that the heat gained would come at the price of winds slowed down: you couldn’t get something for nothing. Sax immediately argued that that would be a side benefit, given the severity of the global dust storms the wind sometimes caused. “A little heat for a little wind is a great trade-off.”

“So, a million windmills,” Ann said now. “And that’s just the start. You talked about spreading black dust on the polar caps, didn’t you Sax?”

“It would thicken the atmosphere faster than practically any other action we could take.”

“So if you get your way,” Ann said, “the caps are doomed. They’ll evaporate and then we’re going to say, ‘I wonder what they were like?’ And we won’t know.”

“Do you have enough supplies, enough time?” John asked.

“We’ll drop you supplies,” Arkady said again.

“There’s four more months of summer,” Ann said.

“You just want to go to the pole!” Frank said, echoing Phyllis.

“So?” Ann replied. “You may have come here to play office politics, but I plan to see a bit of this place.”

Nadia grimaced; that ended that line of conversation, and Frank would be angry. Which was never a good idea. Ann, Ann …

The next day the Terran offices weighed in with the opinion that the polar cap ought to be sampled in its aboriginal condition. No objections from base; though Frank did not get back on the line. Simon and Nadia cheered: “North to the Pole!”

Phyllis just shook her head. “I don’t see the point. George and Edvard and I will stay down here as a back-up, and make sure the ice miner is working right.”

So Ann and Nadia and Simon took Rover Three and drove back down Chasma Borealis and around to the west, where one of the glaciers curling away from the cap thinned to a perfect rampway. The mesh of the rover’s big wheels caught like a snowmobile’s driving chain, running well over all the various surfaces of the cap, over patches of exposed granular dust, low hills of hard ice, fields of blinding white CO

frost, and the usual lace of sublimed water ice. Shallow valleys swirled outward in a clockwise pattern from the pole; some of these were very broad. Crossing these they would drive down a bumpy slope that curved away to right and left over both horizons, all of it covered by bright dry ice; this could last for twenty kilometers, until the whole visible world was bright white. Then before them a rising slope of the more familiar dirty red water ice would appear, striated by contour lines. As they crossed the bottom of the trough the world would be divided in two, white behind, dirty pink ahead. Driving up the south-facing slopes, they found the water ice more rotten than elsewhere, but as Ann pointed out, every winter a meter of dry ice sat on the permanent cap to crush the previous summer’s rotten filigree, so the potholes were filled on an annual schedule; and the rover’s big wheels crunched cleanly along.

Beyond the swirl valleys they found themselves on a smooth white plain, extending to the horizon in every direction. Behind the polarized and tinted glass of the rover’s windows the whiteness was unmarred and pure. Once they passed a low ring hill, the mark of some relatively recent meteor impact, filled in by subsequent ice deposition. They stopped to take borings, of course. Nadia had to restrict Ann and Simon to four borings a day, to save time and keep the rover’s trunks from being overloaded. And it wasn’t just borings; often they would pass black isolated rocks, resting on the ice like Magritte sculptures: meteorites. They collected the smallest of these, and took samples from the larger ones; and once passed one that was as big as the rover. They were nickel-iron for the most part, or stony chondrites. Chipping away at one of these, Ann said to Nadia, “You know they’ve found meteorites on Earth that came from Mars. The reverse happens too, although much less often. It takes a really big impact to jack rocks out of Earth’s gravitational field fast enough to get them out here – delta V of fifteen kilometers per second, at least – I’ve heard it said that about two percent of the material ejected out of Earth’s field would end up on Mars. But only from the biggest impacts, like the KT boundary impact. It would be strange to find a chunk of the Yucatan here, wouldn’t it?”

“But that was sixty million years ago,” Nadia said. “It would be buried under the ice.”

“True.” Later, walking back to the rover, she said, “Well, if they melt these caps then we’ll find some. We’ll have a whole museum of meteorites, sitting around on the sand.”

They crossed more swirl valleys, falling again into the up-and-down pattern of a boat over waves, this time the largest waves yet, forty kilometers from crest to crest. They used the clocks to keep on a schedule, and parked from ten p.m. to five a.m. on hillocks or buried crater rims, to give themselves a view during their stops; and they blacked the windows with double polarization to help them to get some sleep at night.

Then one morning as they crunched along, Ann turned on the radio and began to run checks with the areosynchronous satellites. “It’s not easy to find the pole,” she said as she worked. “The early Terran explorers had a hell of a time in the north: they were always up there in summertime and couldn’t see the stars, and they had no satellite checks.”

“So how did they do it?” Nadia asked, suddenly curious.

Ann thought about it and smiled. “I don’t know. Not very well, I suspect. Probably dead reckoning.”

Nadia became intrigued by the problem, and started working on it on a sketchpad. Geometry had never been her strong point, but presumably at the north pole on midsummer’s day, the sun would inscribe a perfect circle around the horizon, never getting higher or lower. If you were near the Pole, then, and it was near Midsummer’s Day, you might be able to use a sextant to make timed checks on the sun’s height above the horizon … was that right?

“This is it,” Ann said.

“What?”

They stopped the rover, looked around. The white plain undulated to the nearby horizon, featureless except for a couple of broad red contour lines; the lines did not form bull’s eyes circles around them, and it didn’t look like they were at the top of anything.

“Where, exactly?” Nadia asked.

“Well, somewhere just north of here.” Ann smiled again. “Within a kilometer or so. Maybe that way.” She pointed off to the right. “We’ll have to go over there a ways and check with the satellite again. A little bit of triangulation and we should be able to hit it on the nose. Plus or minus a hundred meters, anyway.”

“If we just took the time, we could make it plus or minus a meter!” Simon said enthusiastically. “Let’s pin it down!”

So they drove for a minute, consulted the radio, turned to right angles and drove again, made another consultation. Finally Ann declared they were there, or close enough. Simon programmed the computer to keep working on it, and they suited up and went out and wandered around a bit, to make sure they had stepped on it. Ann and Simon drilled a boring. Nadia kept walking, in a spiral that expanded away from the cars. A reddish white plain, the horizon some four kilometers away; too close; it came to her in a rush, as during the black dune sunset, that this was alien – a sharp awareness of the tight horizon, the dreamy gravity, a world just so big and no bigger … and now she was standing right on its north pole. It was Ls = 92, about as near midsummer as you could ask; so if she stood facing the sun, and didn’t move, the sun would stay right in front of her face for all the rest of the day, or the rest of the week for that matter! It was strange. She was spinning like a top. If she stood still long enough, would she feel it?

Her polarized faceplate reduced the sun’s glare on the ice to an arc of crystalline rainbow points. It wasn’t very cold. She could just feel a breeze against her upraised palm. A graceful red streak of depositional laminae ran over the horizon like a longitude line. She laughed at the thought. There was a very faint ice-ring around the sun, big enough that its lower arc just touched the horizon. Ice was subliming off the polar cap and gleaming in the air above, providing the crystals in the ring. Grinning, she stomped her boot prints into the North Pole of Mars.

That evening they aligned the polarizers so that a very dimmed-down image of the white desert stood around them in the module windows. Nadia sat back with an empty food tray in her lap, sipping a cup of coffee. The digital clock flicked from 11:59:59 to 0:00:00, and stopped. Its stillness accentuated the quietness in the car. Simon was asleep; Ann sat in the driver’s seat, staring out at the scene, her dinner half-eaten. No sound but the whoosh of the ventilator. “I’m glad you got us up here,” Nadia said. “It’s been great.”

“Someone should enjoy it,” Ann said. When she was angry or bitter her voice became flat and distant, almost as if she were being matter-of-fact. “It won’t be here long.”

“Are you sure, Ann? It’s five kilometers deep here, isn’t that what you said? Do you really think it will completely disappear just because of black dust on it?”

Ann shrugged. “It’s a question of how warm we make it. And of how much total water there is on the planet, and how much of the water in the regolith will surface when we heat the atmosphere. We won’t know any of those things until they happen. But I suspect that since this cap is the primary exposed body of water, it’ll be the most sensitive to change. It could sublime away almost entirely before any significant part of the permafrost has gotten within fifty degrees of melting.”

“Entirely?”

“Oh, some will be deposited every winter, sure. But there’s not that much water, when you put it in the global perspective. This is a dry world, the atmosphere is super-arid, it makes Antarctica look like a jungle, and remember how that place used to suck us dry? So if temperatures go up high enough, the ice will sublime at a really rapid rate. This whole cap will shift into the atmosphere and blow south, where it’ll frost out at nights. So in effect it’ll be redistributed more or less evenly over the whole planet, as frost about a centimeter thick.” She grimaced. “Less than that, of course, because most of it will stay in the air.”

“But then if it gets hotter still, the frost will melt, and it will rain. Then we’ve got rivers and lakes, right?”

“If the atmospheric pressure is high enough. Liquid surface water depends on air pressure as well as temperature. If both rise, we could be walking around on sand here in a matter of decades.”

“It’d be quite a meteorite collection,” Nadia said, trying to lighten Ann’s mood.

It didn’t work. Ann pursed her lips, stared out the window, shook her head. Her face could be so bleak; it couldn’t be explained entirely by Mars, there had to be something more to it, something that explained that intense internal spin, that anger. Bessie Smith land. It was hard to watch. When Maya was unhappy it was like Ella Fitzgerald singing a blues, you knew it was a put-on, the exuberance just poured through it. But when Ann was unhappy, it hurt to watch it.

Now she picked up her dish of lasagne, leaned back to stick it in the microwave. Beyond her the white waste gleamed under a black sky, as if the world outside were a photo negative. The clockface suddenly read 0:00:01.

Four days later they were off the ice. As they retraced their route back to Phyllis and George and Edvard, the three travelers rolled over a rise and came to a halt; there was a structure on the horizon. Out on the flat sediment of the chasma floor there stood a classical Greek temple, six Dorian columns of white marble, capped by a round flat roof.

“What the hell?”

When they got closer they saw that the columns were made of ice drums from the miner, stacked on top of each other. The disk that served as roof was rough-hewn.

“George’s idea,” Phyllis said over the radio.