По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

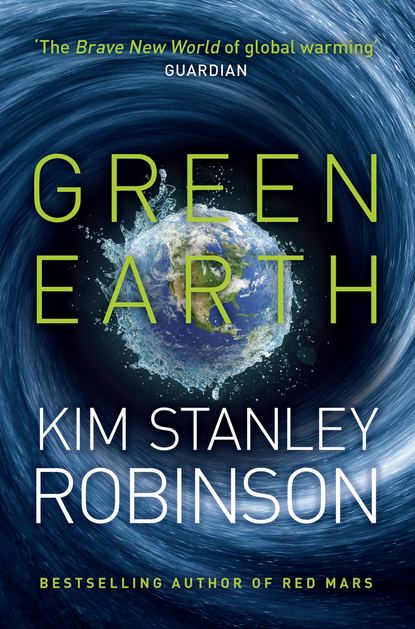

Green Earth

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Frank shrugged, went to the whiteboard, uncapped his red marker. “Let me make a list.”

He wrote a 1 and circled it.

“One. We have to knit it all together.” He wrote, “Synergies at NSF.”

“I mean by this that you should be stimulating synergistic efforts that range across the disciplines to work on this problem. Then,” he wrote and circled a 2, “you should be looking for immediately relevant applications coming out of the basic research funded by the foundation. These applications should be hunted for by people brought in specifically to do that. You should have a permanent in-house innovation and policy team.”

Anna thought, That would be that mathematician he just lost.

She had never seen Frank so serious. His usual manner was gone, and with it the mask of cynicism and self-assurance that he habitually wore, the attitude that it was all a game he condescended to play even though everyone had already lost. Now he was serious, even angry it seemed. Angry at Diane somehow. He wouldn’t look at her, or anywhere else but at his scrawled red words on the whiteboard.

“Third, you should commission work that you think needs to be done, rather than waiting for proposals and funding choices given to you by others. You can’t afford to be so passive anymore. Fourth, you should assign up to fifty percent of NSF’s budget every year to the biggest outstanding problem you can identify, in this case catastrophic climate change, and direct the scientific community to attack and solve it. Both public and private science, the whole culture. The effort could be organized like Germany’s Max Planck Institutes, which are funded by the government to go after particular problems. There’s about a dozen of those, and they exist while they’re needed and get disbanded when they’re not. It’s a good model.

“Fifth, you should make more efforts to increase the power of science in policy decisions everywhere. Organize all the scientific bodies on Earth into one larger body, a kind of UN of scientific organizations, which then would work together on the important issues, and would collectively insist they be funded, for the sake of all the future generations of humanity.”

He stopped, stared at the whiteboard. He shook his head. “All this may sound, what. Large-scaled. Or interfering. Antidemocratic, or elitist or something—something beyond what science is supposed to be.”

The man who had objected before said, “We’re in no position to stage a coup.”

Frank shook him off. “Think of it in terms of Kuhnian paradigms. The paradigm model Kuhn outlined in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.”

The bearded man nodded, granting this.

“Kuhn postulated that in the usual state of affairs there is general agreement to a set of core beliefs that structure people’s theories—that’s a paradigm, and the work done within it he called ‘normal science.’ He was referring to a theoretical understanding of nature, but let’s apply the model to science’s social behavior. We do normal science. But as Kuhn pointed out, anomalies crop up. Undeniable events occur that we can’t cope with inside the old paradigm. At first scientists just fit the anomalies in as best they can. Then when there are enough of them, the paradigm begins to fall apart. In trying to reconcile the irreconcilable, it becomes as weird as Ptolemy’s astronomical system.

“That’s where we are now. We have our universities, and the Foundation and all the rest, but the system is too complicated, and flying off in all directions. Not capable of coming to grips with the aberrant data.”

Frank looked briefly at the man who had objected. “Eventually, a new paradigm is proposed that accounts for the anomalies. It comes to grips with them better. After a period of confusion and debate, people start using it to structure a new normal science.”

The old man nodded. “You’re suggesting we need a paradigm shift in how science interacts with society.”

“Yes I am.”

“But what is it? We’re still in the period of confusion, as far as I can see.”

“Yes. But if we don’t have a clear sense of what the next paradigm should be, and I agree we don’t, then it’s our job now as scientists to force the issue and make it happen, by employing all our resources in an organized way. To get to the other side faster. The money and the institutional power that NSF has assembled ever since it began has to be used like a tool to build this. No more treating our grantees like clients whom we have to satisfy if we want to keep their business. No more going to Congress with hat in hand, begging for change and letting them call the shots as to where the money is spent.”

“Whoa now,” objected Sophie Harper. “They have the right to allocate federal funds, and they’re very jealous of that right, believe you me.”

“Sure they are. That’s the source of their power. And they’re the elected government, I’m not disputing any of that. But we can go to them and say, Look, the party’s over. We need this list of projects funded or civilization will be hammered for decades to come. Tell them they can’t give a trillion dollars a year to the military and leave the rescue and rebuilding of the world to chance and some kind of free market religion. It isn’t working, and science is the only way out of the mess.”

“You mean the scientific deployment of human effort in these causes,” Diane said.

“Whatever,” Frank snapped, then paused, blinking, as if recognizing what Diane had said. His face went even redder.

“I don’t know,” another Board member said. “We’ve been trying more outreach, more lobbying of Congress, all that. I’m not sure more of that will get the big change you’re talking about.”

Frank nodded. “I’m not sure they will either. They were the best I could think of, and more needs to be done there.”

“In the end, NSF is a small agency,” someone else said.

“That’s true too. But think of it as an information cascade. If the whole of NSF was focused for a time on this project, then our impact would hopefully be multiplied. It would cascade from there. The math of cascades is fairly probabilistic. You push enough elements at once, and if they’re the right elements, and the situation is at the angle of repose or past it, boom. Cascade. Paradigm shift. New focus on the big problems we’re facing.”

The people around the table were thinking it over.

Diane never took her eye off Frank. “I’m wondering if we are at such an obvious edge-of-the-cliff moment that people will listen to us if we try to start such a cascade.”

“I don’t know,” Frank said. “I do think we’re past the angle of repose. The Atlantic current has stalled. We’re headed for a period of rapid climate change. That means problems that will make normal science impossible.”

Diane smiled tautly. “You’re suggesting we have to save the world so science can proceed?”

“Yes, if you want to put it that way. If you’re lacking a better reason to do it.”

Diane stared at him, offended. He met her gaze unapologetically.

Anna watched this standoff, on the edge of her seat. Something was going on between those two, and she had no idea what it was. To ease the suspense she wrote down on her handpad, “saving the world so science can proceed.” The Frank Principle, as Charlie later dubbed it.

“Well,” Diane said, breaking the frozen moment, “what do people think?”

A discussion followed. People threw out ideas: creating a kind of shadow replacement for Congress’s Office of Technology Assessment; campaigning to make the President’s scientific advisor a cabinet post; even drafting a new amendment to the Constitution that would elevate a body like the National Academy of Science to the level of a branch of government. Then also going international, funding a world body of scientific organizations to push everything that would create a sustainable civilization. These ideas and more were mooted, hesitantly at first, and then with more enthusiasm as the people there began to realize that they all had harbored various ideas of this kind, visions that were usually too big or strange to broach to other scientists. “Pretty wild notions,” as one of them noted.

Frank had been listing them on the whiteboard. “The thing is,” he said, “the way we have things organized now, scientists keep themselves out of political policy decisions in the same way that the military keeps itself out of civilian affairs. That comes out of World War Two, when science was part of the military. Scientists recused themselves from policy decisions, and a structure was formed that created civilian control of science, so to speak.

“But I say to hell with that! Science isn’t like the military. It’s the solution, not the problem. And so it has to insist on itself. That’s what looks wild about these ideas, that scientists should take a stand and become a part of the political decision-making process. If it were the folks in the Pentagon saying that, I would agree there would be reason to worry, although they do it all the time. What I’m saying is that it’s a perfectly legitimate move for us to make, even a necessary move, because we are not the military, we are already civilians, and we have the only methods in existence that are capable of dealing with these global environmental problems.”

The group sat for a moment in silence, thinking that over. Monsoonlike rain coursed down the room’s window, in an infinity of shifting delta patterns. Darker clouds rolled over, making the room dimmer still, submerging it until it was a cube of lit neon, hanging in aqueous grayness.

Anna’s notepad was covered by squiggles and isolated words. So many problems were tangled together into the one big problem. So many of the suggested solutions were either partial or impractical, or both. No one could pretend they were finding any great strategies to pursue at this point. It looked as if Sophie Harper was about to throw her hands in the air, perhaps taking Frank’s talk as a critique of her efforts to date, which Anna supposed was one way of looking at it, although not really Frank’s point.

Now Diane made a motion as if to cut the discussion short. “Frank,” she said, drawing his name out. “Fraannnnnk—you’re the one who’s brought this up, as if there is something we could do about it. So maybe you should be the one who heads up a committee tasked with figuring out what these things are. Sharpening up the list of things to try, in effect, and reporting back to this Board. You could proceed with the idea that your committee was building the way to the next paradigm.”

Frank stood there, looking at all the red words he had scribbled so violently on the whiteboard. For a long moment he continued to look at it, his expression grim. Many in the room knew that he was due to go back to San Diego. Many did not. Either way Diane’s offer probably struck them as another example of her managerial style, which was direct, public, and often had an element of confrontation or challenge in it. When people felt strongly about taking an action, she often said, You do it, then. Take the lead if you feel so strongly.

At last Frank turned and met her eye. “Yeah, sure,” he said. “I’d be happy to do that. I’ll give it my best shot.”

Diane revealed only a momentary gleam of triumph. Once when Anna was young she had seen a chess master play an entire room of opponents, and there had been only one player he was having trouble with; at the moment he checkmated that person, he moved on with that same quick, satisfied look.

Now, in this room, Diane was already on to the next item on her agenda.

Afterward, the bioinformatics group sat in Anna and Frank’s rooms on the sixth floor, sipping cold coffee and looking into the atrium.

Edgardo came in. “So,” he said cheerily, “I take it the meeting was a total waste of time.”

“No,” Anna snapped.

Edgardo laughed. “Diane changed NSF top to bottom?”

“No.”