По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

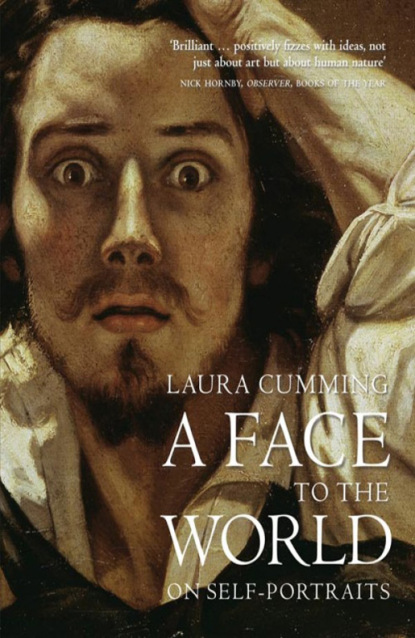

A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Detail of The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, c.1435 (#litres_trial_promo) Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441)

Between this world and the next, near and far, two little figures are posted like watchers on a promontory. One is studying the view from the palace battlements, the other turns slightly, glancing back in our direction. He wears a red turban and carries the rod of a courtier. The crucial fact about this figure is once again its position, on the threshold between two worlds, present and future, and right at the epicentre of the painting. Draw the diagonals and they would meet on a point: the hand of the man in the turban.

The angel in the New Jerusalem, according to Revelation, has a rod to measure the glorious architecture of the city. The measurements of Van Eyck’s New Jerusalem are exceptionally small – the whole picture is only about two feet wide – and his rod is thus sensationally tiny, a microscopic yardstick for a miniature vision. But even without the biblical aside, and Van Eyck’s paintings are always theologically rich, the little man in his eye-catching turban has a modest humour all of his own: discreet enough to escape Rolin’s self-centred attentions, you feel, but there for those who have eyes to see him.

Van Eyck places himself at the crosshairs of his own field of vision; painting the world, and all its contents, he numbers himself within it. This is not narcissism but modest logic: even without a mirror, or reflections, we are visible to ourselves somewhat. Shut one eye and the projecting nose becomes apparent; look up and see the overhanging brow. We have an outer as well as an inner sense of our own bodies that reflections confirm or confound; and catching sight of these reflections, we are made episodically conscious of our own bodily existence – atoms in time, maybe, but nonetheless the viewing centre of our world.

It has been argued that the only reason anyone ever imagines these little men in red turbans might be Van Eyck is because of another painting by him known as Man in Red Turban.

(#litres_trial_promo) Or at least that was its title until very recently when visual evidence was finally allowed to outweigh academic caution just a fraction and scholars relabelled it Portrait of a Man (Self-Portrait?).

(#litres_trial_promo) In fact, there is a faint long-nosed resemblance between this man and the courtier with his rod that has nothing to do with turbans; and turbans are in any case off the point.

Van Eyck stares piercingly out of the picture, a tight-lipped man with fine silver stubble. His look is shrewd, imperturbable, serious. The eyes are a little watery, as if strained by too much close looking, and there is a palpable melancholy to the picture. Look closer, as Van Eyck’s art irresistibly proposes, and you notice something else – that the eyes are not in equal focus. The left eye is painted in perfect register and so clearly that the Northern light from the window glints minutely in the wet of it – the world reflected; but the other is slightly blurred, you might say impressionistic. These eyes are trying to see themselves, have the look of trying to see themselves in some kind of mirror. ‘Jan Van Eyck Made Me’ is written below the image. Along the top runs the inscription ‘Als ich kan’ – ‘As I can’, and punningly ‘As Eyck can’.

Van Eyck painted the ‘Als ich kan’ motto on the frames of other portraits too but it is far more emphatically displayed here to create the illusion that it has been carved into the gilded wood itself. It also appears where he normally names the sitter. But more than that, its play upon the first and third person epitomizes the I-He grammar of self-portraiture to perfection. Here I am, gravely scrutinizing my face in the mirror, and the picture; there he is, the man in the painting.

I am here. He was here. ‘Jan Van Eyck fuit hic’ is written in an exquisite chancery hand on the back wall of The Arnolfini Portrait. Ever since Kilroy was here and everywhere in the twentieth century the phrase has epitomized graffiti, which is, in its elegant way, exactly how Van Eyck uses it.

Everyone knows the Arnolfini – the rich couple with the dog, the oranges, the mirror and the shoes, touching hands in an expensively decorated bedroom. But nobody knows quite what they are doing there, in a bedroom of all places, an intimacy unheard of in Flemish portraiture. This joining of hands, is it the moment of betrothal, the marriage itself, the party afterwards, or nothing to do with a wedding? The bed awaits with its heavy scarlet drapes, the dog hovers, the texture of its fur exquisitely summoned all the way from coarse to whisper-soft. Perhaps he is an emblem of fidelity; perhaps this is a merger between two Italian families trading in luxury goods, as lately suggested, but all interpretations are necessarily reductive for none can fully account for the strange complexities of the painting. Even if one knew precisely why Giovanni Arnolfini was raising his right hand as if to testify he would still be a peculiarly disturbing presence, with his reptilian mask and lashless eyes, dwarfed beneath a cauldron of a hat. He touches, but does not look at the woman. She struggles to hold up the copious yardage of a dress that nobody could possibly walk in. Behind them is that writing on the wall that makes so much of the historic moment, and beneath that is the legendary mirror in which Van Eyck is reflected (in blue), entering into the scene.

Jan Van Eyck was here. It is not strictly accurate in terms of tense, of course, for Van Eyck has to be here right now as he paints his story on the wall. He sends a message to the future about the past, but it is written in the present moment; the paradox is its own little joke, as for every Kilroy. But the mirror also tinkers with the tense of the picture. Without it, you would simply be looking at an image of the past, a time-stopped world of wooden shoes, abundant robes and a sign-language too archaic to decode. But things are still happening in the mirror, a man is on the verge of entering, life continues on our side – the painter’s side – of this room. For Van Eyck invented something else too, not just a new way of painting but the whole idea of an open-ended picture that extends into our world and vice versa. Just as his reflection passes over the threshold to enter the room where the Arnolfini stand, so he creates the illusion that we may accompany him there as well. The tiny self-portrait is the key to the door. Art need not be closed.

Detail of The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434 (#litres_trial_promo) Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441)

The inscription in The Arnolfini Portrait announces the artist’s role as witness and narrator – I was here, this was the occasion – though the self-portrait says something more about the reality depicted. The liquid highlights in the eyes, the pucker of orange peel, the flecked coat of the dog, the embrasure of clear light, reflected again in the brass-framed mirror: the whole powerfully real illusion was contrived by Jan Van Eyck, transforming what he saw into what you now see here. He is there in the picture connecting our world to theirs, a pioneer breaking down frontiers.

As usual, the painter makes no spectacle of himself. Van Eyck’s self-portraits are conceivably the smallest in art, certainly the most discreet, yet their scale is in inverse ratio to their metaphysical range. The visible world appears to be outside us, viewed through the windows of the eyes, and yet it contains us all.

2 Eyes (#ulink_8c2d6397-8cde-5c9a-9b1d-b0f2c36d8a99)

‘There is a road from the eye to the heart that does not go through the intellect.’

G. K. Chesterton

Detail of The Adoration Of the Magi, 1475 (#litres_trial_promo) Sandra Botticelli (c. 1445–1510)

It would be hard to think of a more unnerving stare in Renaissance art than that of Sandro Botticelli, a painter better known for his dreamy visions of peace and love than for undertones of menace and coercion. Botticelli looks back at you, what is more, from a scene that ought to be all hushed and hallowed joy, the arrival of the wise men at Christ’s nativity. But even without his presence there is a sense of threat, for the miraculous birth has taken place in a derelict outhouse of yawning rafters and broken masonry that looks on the brink of collapse.

Between the viewer and the Holy Family, hoisted high for maximum visibility, mills a large crowd showing very varying degrees of respect, all played by members and attendants of the Florentine Medici. Botticelli includes two of his current patrons, Lorenzo and Giuliano, but also Piero the Gouty and Cosimo the Elder, both of whom were already dead at the time of painting. At the far right of this hubbub, in which at least two of the posse seem more adoring of their bosses than the Christ child, stands the artist himself. Stock still, full length, perfectly self-contained, he is the only figure set apart from the scene, muffled in his mustard-yellow robes like an assassin in a crowd, a Banquo’s ghost of a presence apparently visible only to us. The face is sullen, disdainful, unrelentingly forceful, the eyes trained upon you with a stare as cold as Malcolm McDowell’s in the poster for Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. A face, incidentally, that runs counter to the comfortable dog-and-owner theory of self-portraiture that artists tend to look right for their art – Van Gogh a fiery redhead with startling blue eyes, Rembrandt a rich ruin of a face – for it has no affinity with the sensuous rhythms of his work. The artist stands out not because he stands apart, but because of the look he gives the viewer. With a single glance, Botticelli turns the biblical scene into a confrontation.

Why is he here? What occasions his presence? Self-portraits often raise the question of their own existence. You might ask what could possibly justify the casting of the Medici as worshipful Magi, the rich miming the faithful, but this is obviously commemoration in the form of ostentatious prayer. Odd as it may seem to include a couple of deceased Medici, it was an expedient way of keeping their images alive before God and the congregation of Santa Maria Novella, just as Lorenzo and Giuliano would be eternalized in their turn; and if the patrons could appear in this elaborate fantasy, viewing and queuing and even occasionally stooping in awe, then why not the author of the painting itself?

Savonarola, apocalyptic preacher, burner of vanities and scourge of Florentine corruption who would later count Botticelli among his followers, railed against the shocking preponderance of secular portraits in religious frescos in those days. The churches were becoming a social almanac, a portrait gallery for local mafias. There they would be, witnessing martyrdoms, watching miracles, gazing at the Crucifixion – anything to appear in the picture. At least Botticelli did not cast himself as a wise man, but he does not play the family retainer either. His presence, his look, has a far greater purpose: to intensify the whole meaning of the painting.

The Adoration of the Magi, 1475 (#litres_trial_promo) Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445–1510)

Eye-to-eye portraits were comparatively unusual in fifteenth-century Italy and congregations rarely saw a recognizable face looking directly back at them from a church fresco. Patrons generally appeared in worshipful profile. The sitters in independent portraits – paintings you could hang on the wall at home – were commonly presented in profile too, like a head on a medal, distanced and aloof, partly because they were often transcribed directly from frescos in the first place but also perhaps because profiles are so precise and economic, an enormous amount of information condensed and carried by a single authoritative line. The compiler of an inventory of paintings in Urbino in 1500 is surprised to come across a portrait ‘with two eyes’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Until Flemish portraits by Van Eyck and others started to arrive in Italy, with the revelation of a three-quarters view, it was unusual for a portrait to show more than one eye. This shift towards the viewer, this turning to communicate, was beginning to happen when Botticelli painted the senior Medici as Magi, but they still have the idealized remoteness of dead legends, whereas a singular vitality radiates from his eyes. The eyes are the strongest intimation, of course, that this is a self-portrait.

But Botticelli is not just putting in a proprietorial appearance, the painter painted. In The Adoration of the Magi, the self-portrait activates both the scene and its meaning. Just by turning and looking so challengingly at you, he shifts the tense so that the nativity no longer seems like ancient history but an incident of the moment, its significance forever urgent. There is fixation in that look, not just born of strained relations with the mirror, but perhaps of the kind that made Botticelli labour for twenty years over his never-finished illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy, or that would eventually drive him to destroy his own paintings in Savonarola’s notorious bonfire of the vanities. At any rate, the stare is a deliberate pressure, almost a demand or accusation. You who look so complacently upon this scene that I have envisaged for you – how deep is your adoration, your love?

Self-portraits catch your eye. They seem to be doing it deliberately. Walk into any art gallery and they look back at you from the crowded walls as if they had been waiting to see you. The eyes in a million portraits gaze at you too, following you around the room, as the saying goes, but rarely with the same heightened expectation. Come across a self-portrait and there is a frisson of recognition, something like chancing upon your own reflection.

This is self-portraiture’s special look of looking, a trait so fundamental as to be almost its distinguishing feature. Even quite small children can tell self-portraits from portraits because of those eyes. The look is intent, actively seeking you out of the crowd; the nearest analogy may be with life itself: paintings behaving like people.

Eye-to-eye contact with others – a glance, a stare – is the purest form of reciprocity. Until it ends, until one of us looks away, it is the simplest and most direct connection we can ever have. I look at you, you look at me: it is our first prelude, an introduction to whatever comes next; if we smile, shake hands, converse, get married, it will always be preceded by that first glance. We talk of eyes meeting across a crowded room, of recognizing each other immediately even though we had never met; we speak of love at first sight. Conversely we could not stand the sight of each other. Just one look was enough.

Since painted faces cannot hold your interest by changing expression, much depends on the character of that look. It is the first place we go, as in life, and if it is too tentative or blank or disaffected it might also be the last; the overture rebuffed. Some artists are disadvantaged from the start because they cannot get a fix on their eyes in the mirror, an aspect of excruciating strain that shows up in the picture exposing the pretence that they were ever looking at anyone but themselves. Others have to deal with spectacles or myopia or some insurmountable affliction, although the Italian painter Guercino movingly transformed the brutal squint he suffered from birth (Guercino means squinter) into a sign of unimpaired imagination by painting his eyes so deeply shadowed that one understands that this man’s vision turns inwards. His self-portrait shows, by concealment, what it might be like to have partial sight; mutatis mutandis, one sees what he sees. This is in the gift of self-portraits with perfect sight too of course. Whenever the look that originates in the mirror stays live and direct in the final image then the viewer should have a vicarious experience of being the artist – standing in the same relation he or she stood to the mirror, and the picture.

Self-Portrait, c. 1546–1548 (#litres_trial_promo) Jacopo Comin Tintoretto (15I8–1594)

This sharpening of vision is very marked in a self-portrait Jacopo Tintoretto made in his late twenties. The Venetian turns to look our way and there is inquiry in his dark-eyed stare, a hook so strong you cannot immediately pull away for the sense of being held in his sights. The look is charged, the intensity meant, and abetted by other aspects of the image: the turning to stare over one shoulder, the gathering frown, appearing to cast a cold eye upon oneself in the encroaching darkness – no illusions, no fears – not to mention Tintoretto’s burning good looks.

It is an obvious and much-remarked fiction of self-portraiture that the viewer, rather than the artist, is the focus of all this intense interest. Tintoretto perfects the illusion. He has not gone right through the looking glass the way some artists do, their eyes worn blank by staring; he is not lost in self-contemplation, not caught in some infinite regression of looking at himself looking at himself, and so on. He is all attention.

The eyes are unusually large as if they dominated the other senses. Light catches the upper lid of the left and the lower rim of the right so that one has an uncommon sense of their spherical form within the socket. Perhaps these are the red rims of a man who painted with insomniac drive right through the night, creator of the tumultuous murals that cover wall after wall of the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice. At any rate, the eyes have their own special force of character and they have the reciprocal effect of making the viewer stare hard in return. It is no stretch of the imagination to feel you are both equally intent upon the other, but that you have also slipped into his position, seeing what he saw, entering into his self-knowledge. Centuries before anyone discovered how the eye actually works, Tintoretto has hit upon a true metaphor, for the eye is indeed an extruded part of the brain, drawing whatever it can of the outer world in through the retina to be transformed into neural images. Nowadays some specialists consider the eye a part of the mind itself, its freight of information modified by individual cognition, and even in Darwin’s day its curious status was enough understood for him to have written that ‘the thought of the eye makes me cold all over’.

(#litres_trial_promo) But Tintoretto, without any knowledge of the mechanics of seeing, senses the connection between mind and eye: to see is to know.

Look at me when I am talking to you, we say in pain or exasperation to those who have turned away – putting us out of sight and by implication out of mind. The simplest way for anyone to thwart our attentions, to block our access, is to look away. The barman who does not want to take an order will not meet the customer’s eye. The pedestrian who has stepped out in front of the car looks into the middle distance to avoid the motorist’s glare. An especially chilling way to deny another person is to stare straight through them as if they were just not there.

Self-Portrait, 1813 (#litres_trial_promo) Anton Graff (1736–1813)

Self-Portrait with Spectacles, 1771 (#litres_trial_promo) Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779)

This is precisely the look of many portraits where the sitter is supposedly a cut above – the royal portrait, say, or the duke on horseback – but most portraiture aims for some kind of connection. The Italian artist Giulio Paolini made the point in the 1960s by showing just how disconcerting it feels if this communion is deliberately thwarted. Paolini displayed a black and white reproduction of a Renaissance painting, Lorenzo Lotto’s Portrait of a Young Man, which shows a beautiful youth staring very candidly, and captivatingly, back at the viewer; or so it seems. But Paolini killed that illusion at a stroke simply by calling his version Young Man Looking at Lorenzo Lotto.

Common sense says this can only be true, that the sitter’s eyes were always on Lotto while he worked; but common sense is exactly what we naturally suppress when looking at the eye-to-eye portrait. It is our willing suspension of disbelief, our contribution to the occasion, and if the young man is no longer looking at us, if his eyes are refocused on someone else, then the party is over. The painting withdraws, becomes the record of two dead people looking at each other in some previous century, an effect of deflation and exclusion. It is the end of the rapport most portraitists want and exactly the opposite of self-portraiture’s aspiring eye-to-eye transmission of a first person encounter.

But an inept self-portrait will prove Paolini’s point quite unintentionally just by botching the eyes. The artist gets into a loop of looking at himself in the glass and reproducing that look that meets nothing but itself.

The Swiss-born painter Anton Graff is doing his best to see what he looks like, visor in position, brows pinched with effort. He poses as if turning aside from his latest commission, a portrait of some portly and presumably once-famous patron, but the pretence is not plausible for a moment. The Graff in the picture who wants to show himself doing what he does best – he was a very successful portraitist whose sitters included Schiller, Gluck and Frederick the Great – cannot really be working on that portrait, since he must be working on this self-portrait instead. And sure enough, he is trying so hard to paint both eyes in focus that you know he is really painting his own face. Graff’s gaze swithers; he cannot see us for the struggle to see himself.

A few decades earlier, Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin looks over the top of his pince-nez, one eyebrow raised with perceptible interest in an attitude of scrutiny that could not appear more sociable by comparison. The pose is almost humorous – who is not familiar with the rhetoric of lowering one’s spectacles as if pretending to consider someone else more pointedly – and the artist is at home in his jaunty bandanna, neck cloth loosely knotted against the cold, a note of domestic intimacy that runs through his work. But Chardin, now in his seventies, is both watchful and grave.

His eyesight failing and the smell of the oil paint he had used for half a century now making him ill, Chardin was forced to give up oil for pastel instead. The light focusing through the lens, the steel frames, the eyes with their glint of curiosity: all are achieved with this tricky medium, so easily blended and yet so fragile and fugitive.

Chardin is one of those artists whose self-portrait comes as a surprise – not because the face is so intelligent, for he has to be at least this clever to be the greatest still-life painter in art, but because it exists in the first place. Born in Paris in 1699, he never left the city except for a trip to Versailles. He has nothing to say about the wars, politics or public misery of his times, still less the private excesses of the aristocracy, although he must have seen it all for he had a city-centre flat in the Louvre. Chardin stayed at home, secretive, industrious, painting his apricots, strawberries and teacups, hymning the softness of a dead hare, the molten glow of a cherry. His power of touch runs all the way from the silvery condensation on a glass of water to the reflected glory inside a copper pan and the downy cheek of the housemaid dreaming over her dishes. Diderot, his earliest champion, called him ‘The Great Magician’, trying to fathom the mysteries of his art, of those muffled rooms where everything is misty and slightly distanced and warm air circulates like breath. But nobody ever saw him paint and scarcely a single anecdote attaches to Chardin’s life. That he should have left anything as personal as a self-portrait goes against the person of his art.

Self-Portrait, Wide-Eyed, 1630 (#litres_trial_promo) Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–69)

That it is outwardly turned and makes such vivid eye contact is even less to be expected. For the look is distinctly interpersonal, making a quizzical connection with the viewer from the centre of the image, the perceptual heart of the picture. Chardin turns the same unhurried, penetrating gaze upon himself normally used to gauge the weight of a plum, the quiddity of an egg. You feel what it is to be one of his subjects, and what it is to be Chardin, eyes testing the truth of life directly.

Rembrandt is acting with his eyes. He hooks you by reeling back and showing the whites. The etching has been given the title Self-Portrait, Wide-Eyed but it might as well be called ‘Shocked to See You’. It is as if you personally have caused this effect: you come before him and he reacts, that is the one-two action of the image. The meeting of eyes amounts to an incident. And it is the same with almost all of Rembrandt’s self-portraits: he paints the eyes as pinpricks in shadow, or black holes, or dark discs you have to search for in the gloaming, trying to make the man out. He squints and he leers and he creases up to get a better look at you, a better sense of who you might be, identity always at issue.