По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

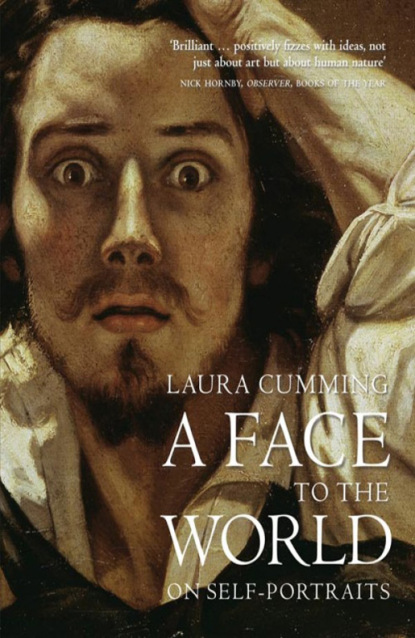

A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Self-Portrait, c. 1655 (#litres_trial_promo) Lorenzo Lippi (1606–65)

One of Rembrandt’s contemporaries, the Florentine poet and painter Lorenzo Lippi, goes even further with this line of inquiry, this idea that artists’ eyes do not just follow but actively seek you out, questioning who you are, with comic trepidation in his case. Lippi turns timidly towards us from the safety of the shadows, one eye out of sight as if hiding round the corner, the other swivelling fearfully in its socket. Who is there? The picture puts everyone on the spot.

Lippi’s ambition, he said, was to write poetry as he spoke and to paint as he saw

(#litres_trial_promo) and this likeness is quick and colloquial. But it is also a neat parody of the eyeballing business of self-portraiture: here is an artist bold enough to paint a portrait of himself yet who seems almost too scared to look. He has one eye on the viewer’s amusement.

Lippi seems to have been better known for his humour than his portraits in any case, spending much of his life at the court of Innsbruck painting respectful likenesses of the aristocrats while at the same time writing a serial mock epic satirizing their behaviour and mores to the mirth of devoted readers back home.

(#litres_trial_promo) His jesting image is now in the Uffizi self-portrait collection, still amusing the people of Florence. Unlike most of the many hundreds of paintings in that collection, it was not made especially for the occasion yet seems to have its current neighbours in mind, a mouse that hardly dares squeak among the great lions all around it whose pomp it quietly mocks. With his one-eyed peep Lippi achieves in a blink, what is more, what other artists can only hope for: an intimacy of connection, a kind of wink, in his case, that immediately brings the self-portrait to life.

Where to look? Anywhere but the mirror is an answer for the rare artist who rejects the rhetoric of intimacy. One of the few self-portraits to avoid eye contact altogether is also one of the greatest, painted by Titian in his mid-seventies. By now, the artist’s patrons have long since included popes, dukes, doges and most of the crowned heads of Europe and he shows himself as splendidly dressed as any of them, wearing the gold chains given him by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V who is supposed to have bowed his own knee to retrieve one of Titian’s dropped brushes (a folk-tale so gratifying to later artists that more than one painted the royal genuflection).

Titian sits at a table, this painter of kings and king of painters, one hand tensed against it, the other braced upon his thigh with the fingers powerfully outspread. A fellow artist who had been admitted to his studio in Venice reported that in these later years Titian often painted directly with his fingers, and one might imagine that the artist painted these magnificent hands with his own fingers, his supreme sense of touch evident in their very tips. But Titian is not painting in this self-portrait, of course – he is waiting, and this is the central tension of the picture. The body faces front, massively present, but the eyes turn away towards some invisible point beyond the picture. That you should still be here, that he should be here at all: these are the burdensome but inevitable conditions of self-portraiture, of appearing and being seen. But Titian manages to command your attention by diverting it, his eyes glancing free of yours.

Where to look when submitting oneself to scrutiny? It is a question that presents itself to the public-minded self-portraitist every time. In reality, we usually have some sense of who might be looking at us, especially if the circumstances are familiar. But artists can only see one person looking back from the mirror and have to imagine all the rest – anyone and everyone who might one day see their image – to compose a representative face. The politician filmed in some satellite studio unable to see his interrogator may be analogous, having no rival eyes on which to latch and forced to frame an expression without any guiding response. Under these circumstances, interviewees frequently look up, down or wanderingly off-centre, flustered by the voice in their ear, infuriated by the questions, or just withdrawn into tense concentration.

Self-Portrait, c. 1560 (#litres_trial_promo) Titian (c. 1488–1576)

The eyes of self-portraits can expose an artist in just this way as dazed or perplexed, lost in drought or self-consciousness, or just defeated by the harsh technicalities. But few have retreated so far into self-consciousness as to have forgotten the world altogether. No matter how intimate the exchange between self and self-image, not many self-portraitists address only themselves, muttering alone in the studio. Self-portraiture is rarely an act of total introspection; attention is what it generally seeks. Some artists aim straight for the public address; others do so while making a pretence of seemly privacy – lowering the eyes, looking away off into the distance. Still others simply want to appear intimate, without giving much away. Joshua Reynolds manages to combine all three just by playing upon vision as a conceit.

Reynolds painted a great number of self-portraits with the public squarely in mind and many of them are unbearably self-serving. But in the best and most original, painted in his mid-twenties when he was just up to London from a Devonshire village and about to set off for the glories of Rome, his sights are set on the future and the road is open before him.

The dynamic young hero stares straight ahead, shielding his eyes against the light with one hand. Literally, he is looking at himself in the mirror but the gesture implies far wider horizons. With the maulstick held across the body like a sword, he also looks ready for the cut and thrust. He is on guard: the artist as saluting swordsman.

It is a variation on the studio self-portrait – the palette, the stick for steadying the hand at the canvas, even a hint of that canvas – but such an advance on the usual scenario. Reynolds makes a character of himself in a drama that is all about seeing and being seen and trying to get a better look at the world. The world, and himself, and his audience, and his painting – the gesture is pointedly specific yet all-encompassing; and then comes a further twist. His eyes are so deep in shadow, like those of Rembrandt, Reynolds’s hero, that it is impossible to tell whether they are truly fixed upon the viewer; and the implication of that shielding hand, what is more, is that it is in any case too bright to make out what lies ahead, that the artist can hardly see. Artist and viewer are ships in the night. Yet the hand against the light tells of a sighting!

‘A beautiful eye makes silence eloquent, a kind eye makes contradiction an assent, an enraged eye makes beauty deformed. This little member gives life to every other part about us; that is to say, every other part would be mutilated were not its force represented more by the eye than even by itself.’

Joseph Addison

Self-Portrait, c. 1747–49 (#litres_trial_promo) Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–92)

Reynolds painted himself in Rembrandt beret, in the doctoral robes of Oxford University, contemplating a bust of Homer in the manner of Aristotle in Rembrandt’s etching. His sense of achievement was highly developed and his self-portraits are ceremonial – the one painted when he got the freedom of his home town, the one for the king when he took over the Royal Academy – and made for public display within a month or two, usually at the Royal Academy. But he sometimes produced less grandstanding works in which he comes more modestly downstage. In a late painting, now deaf, he cups a hand to his ear the better to hear us in a poignant reprise of this early gesture (his vision would eventually fade as well). Both pictures have a theatrical intimacy – Garrick on stage – that seems to single you out, to signal to you and you alone. They crave, and declare, an audience with these focusing gestures. But although Reynolds salutes the viewer, he has eyes not just for you but the whole wide world.

The eyes of most self-portraits are outwardly directed, seeking to be seen, but they may signify inner vision just as keenly. A head in close up, eyes like dark stars, was rare when Tintoretto painted himself in the sixteenth century but it became very common with Romanticism. The self is concentrated in the mind, the mind in the eyes, twin wells of feeling and thought. Cogito ergo sum translates as video ergo sum, and what I am may be manifest in my powers of vision. Self-portraiture’s special look goes well with this idea of the artist as seer, possessing gifted powers of insight. It is a look popular among the young – Samuel Palmer, at twenty-one, appears charismatically far-sighted, although it is partly the effect of not being able to draw both eyes in focus – and mocked by Picasso in old age. At ninety-one, eyes like mismatched marbles in a primitive mask, one dim and myopic, the other stuck open for ever like some dreadful twist of fate, he is halfway between animal and crazed old totem.

Absorption, 1919 (#litres_trial_promo) Paul Klee (1879–1940)

There is a little self-portrait drawing by Paul Klee where the eyes are tight shut, so that one deduces that it cannot have been made by looking in a mirror but must effectively be a self-portrait from within, and quite possibly with sex in mind, for there is orgasmic concentration in the features. But what it enchantingly expresses is this idea that inspiration, vision, imagination, soul, everything that really matters in art, come in the end from within. And an extra quirk is that humorous Klee can never be accused of self-regard (an old accusation against self-portrayers) for he was not even looking at himself. What these eyes must have seen, what thoughts, what dreams: Klee’s self-portrait draws one intensely into his mind without following the usual invitation through the open eyes, a sweet retort to the old line about souls and windows. And one remembers that he did not make any distinction between the inner and outer worlds in his work. ‘Art does not render the visible,’ Klee said, ‘it renders visible.’ He was speaking mystically and what is rendered visible in his art is surely at the very least his own spirit – lightsome, benign, visionary, intimate and as comical as this little self-portrait.

What the eyes have seen, literally and metaphorically: this is the concern of all art. In this sense the eyes are the artist’s truest emblem and attribute. How perfect that they should also become the crux of an artist’s self-portrait, the focal point, the first line of communication between artist and viewer.

Yet no self-portraitist actually needs to meet our gaze directly to exert continuous pressure or keep our eyes upon his. This is nowhere more apparent than in an etching by Francisco Goya that speaks as powerfully with the eyes as Botticelli even though it does not even have the advantage of two and never fixes fast, or unequivocally, upon the viewer.

Goya turns slightly out of formal profile, throwing a sidelong glance out of the picture. The look is withering, as pungently directed outward as inward. It is an opening shot; it is the etching with which he prefaced Los Caprichos.

This volume of prints, unsurpassed in their terrifying visions of human violence and folly, avarice and cruelty, their riddling captions like the overheard speech of mysterious offstage commentators, goes so far beyond explanation into nightmare that it is often perceived as purely a figment of the artist’s tormented imagination, no matter that the voice of the captions declares ‘I saw this’ or ‘I was here’. Goya originally opened the volume with that deathless image of a man slumped over his desk, the air thronged with bats and evil critters that might indeed be issuing from his nightmares; and ‘The Sleep of Reason’ has been taken as an allegorical self-portrait depicting the source (and modus operandi) of all that follows. But Goya replaced it, significantly, with this likeness of himself as a top-hatted man of the world casting a cold eye upon the viewer.

Self-Portrait, pub. 1799 (#litres_trial_promo) Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

It is an acerbic pastiche of the conventional famous-author portrait that has prefaced so many books, then and since. The profile puts the self-portrait straight into the third person: there is the author, Señor Goya, his name written below, corresponding precisely with Goya’s verbal description of himself throughout as el autor, or el pintor. And yet he breaks out of that profile, as if coming alarmingly alive. Facing left, he appears to turn his back upon what follows as if in disavowal; but then again, isn’t he rather like the kind of figures who occasionally turn up in the book? Goya may be the maker, or the narrator, but he is not above the vileness depicted herein.

We always say that in his images of sexual corruption, torture, war crimes, bullfights, Goya is the master of modern documentary, that whatever he had to say about the Spanish Inquisition or the horrors of the Napoleonic invasions of the early nineteenth century applies to Afghanistan or Abu Ghraib. The priest lusts, the paedophile rapes: the artist has seen it all and brought it back to us in its absolute horror. But it is very hard to read the tone of Goya’s art, to know who is speaking, who saw what, whether the talk is ever straight.

Look at that telling eye: it seems to swivel between there and here, then and now, between immediacy and distance. Pose and eye, taken together, make Goya both an observer and a man observed, the creator but also the subject. Yet the look is insinuating, and deviously incorporates the viewer. That left eye, half obscured by the heavy eyelid and nearly disappearing out of view, has you snared in its sights, for you and I are part of this too.

3 Dürer (#ulink_7d792f61-fb5f-5739-a492-a33ebbe1dce2)

‘You make us to thyself and our hearts are restless until we find rest in thee.’

St Augustine

Self-Portrait, 1500 (#litres_trial_promo) Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

One winter’s day in 1905, a museum guard was meandering through the galleries of the Alte Pinakotech in Munich when he noticed that one of the paintings had changed since the last time he looked. The eyes of Albrecht Dürer’s self-portrait, the most famous eyes in the museum – the most famous eyes in German art – had somehow lost their piercing charisma. The right eye appeared dim and the liveliness of the left severely diminished, as if they could no longer see, and when the painting was taken down, ferocious little rips were discovered in the irises and pupils that had most likely been made, it was agreed, with the tip of a hatpin. The man – or woman – who assaulted the painting may well have used such a weapon, swift, efficient and very conveniently produced and concealed, for it appears that nobody noticed the attack. Somebody unseen, somebody who was never caught, had tried to put out Dürer’s eyes.

Dürer’s eyes – this is how we put it, not bothering to distinguish between the painter and his self-portrait; and we do the same with portraits too. Mona Lisa is what we call both the picture and the young lady from Milan who sat for Leonardo da Vinci. But it feels more natural with self-portraits since artist and sitter are one and the same, being in some profound sense related, image to person. And in the case of Dürer’s 1500 self-portrait, as never before in the history of art, the one would become the counterpart of the other in unique and mysterious ways.

The impact of this painting cannot be overstated: so immediate and yet so remote. At a distance it seems to transmit an unearthly glow that draws viewers across the gallery, and the power intensifies the nearer one gets, not least because the picture is such an unqualified close-up. Dürer presents himself front on, waist up, formidably fixed, immediate and erect. One of his hands is just out of view, as if under the counter, the other fingers the tufts of his fur lapel in a curious gesture that draws attention to both the garment and the wearer, so present and correct, this man who is representing himself. His long moustache is waxed in two scimitar curves that echo the fine arcs of his eyebrows. The hair streams down over his shoulders, a triangle of metal-bright locks, not a single tendril out of place. The face is closed and eerily symmetric. Above all, the eyes transfix.

Even if you knew nothing about German society in 1500, or this period in art, you could assume that Dürer’s contemporaries were amazed by this self-portrait because it still astonishes today. No gold is used in the paint, apart from the inscription, and yet the picture has this peculiar golden radiance. The face appears exceptionally precise and distinctive – strong nose, more of a limb than a feature; slight cast in the eyes; blemish on the left cheek – yet the evidence, for all its heightened clarity, is bizarrely impersonal. What colour are those pale eyes? How old is this person? What is the expression in his look, so pertinacious and yet so withheld? The picture seems both immeasurably more than – and yet strangely unlike – other self-portraits.

It is a double take so improbable one hardly believes it at first. The long hair, centre-parted, the beard and moustache, the gesture of the fingers, the symmetry and stillness and remoteness of countenance, out of time and out of this world: the resemblance startles, incredulity immediately sets in and yet the thought builds like a quake. Is it just chance, a coincidence of fate, or could this man actually have meant to make himself look like Jesus?

People attack portraits when they no longer see, or want to see, them as pictures so much as surrogates or even real people. This is especially true of statues, which are abused exactly as if they were alive, their noses broken, their genitals mutilated, heads and hands brutally severed. Painted people ought to be less vulnerable, safe indoors and protected by guards, but they are victimized too and the connection between people and pictures is held to be so much closer that unlike statues – sightless objects, things apart – we commonly class them together. Nobody would dream of correcting a child who points to a baby in a book, and calls it a baby instead of a picture, and the same is true of our portraits. Even grown-ups plant kisses on images, carry them like champions through the streets, worship them, savage them out of spite or fury, become excited by them as we are excited by people in reality. What is so singular about Dürer’s image, in this respect as in so many others, is not that it has been adored or loathed but that it has excited both extremes of passion and to a greater degree than any other portrait.

This old painting of a man with prodigious hair and alarming eyes has been kissed and excoriated, worshipped and attacked, carried through the streets and mounted on an altar like an icon. It has been accused of self-love and sacrilege and shocking froideur, in spite of which, or perhaps because of which, women have loved it like a man. The German writer Bettina von Arnim became so infatuated with it – or him – that she had a copy made, one she would send to Goethe, for whom she also felt unrequited love, on the curious grounds that it was so precious to her that she might as well be sending herself.

(#litres_trial_promo) But was von Arnim in love with the portrait, or the man, or the idea of an artist who could create such an image? The idea that image, man and artist might somehow be one and the same, a trinity, may well be the most potent claim of self-portraiture.

In any case indifference is not what Dürer’s painting invites or inspires, and this sense of agency is crucial to its power; for all its preternatural stillness, the self-portrait feels almost oppressively vital. Just as things seen in a dream may seem clearer than those in the waking world, so one imagines that this self-portrait might have appeared more vivid than the real man himself, and perhaps the attacker felt this vitality was focused in the eyes. The damage to the self-portrait was clinically specific: just the irises and pupils, not the whites or any other part of the face, as if whoever tried to blind him could not stand the drilling fixity of Dürer’s gaze.

Mercifully the rips did not penetrate the Renaissance varnish and the painting was successfully repaired, except for a minuscule spot of dullness in one of the eyes that is invisible to our own but was fastidiously noted in the museum records. It is here that the details of the crime have been buried for almost a century. Museums do not often acknowledge – are perhaps even embarrassed by – the power of art to entrance, frighten or enrage and any viewer affected to the point of violence is inevitably described as insane. So it was with the unknown assailant at the Alte Pinakotech, who is described as categorically mad in the records. This may have been the case; the paranoid and delusional often believe that paintings are staring at them. But among the dry reports of each minute abrasion, the experts cannot help wondering whether the painting itself supplied motive. Why was the painting attacked? Because of the way it looked at its attacker, of course, a person presumed to have ‘taken exception to Dürer’s penetrating stare’.

(#litres_trial_promo) It is not beyond belief, even among those who make strong professional distinctions between art and life, that someone – anyone – might experience the eyes as a personal affront. But it is also possible that the attacker may have taken exception to more than the artist’s stare.

All self-portraits are prefaces of a sort. Just as our faces in some sense introduce us, so these painted faces are perceived – and treated – as the prefaces to artistic utterance. They are reproduced on the covers of autobiographies, monographs and fictional lives. They are displayed at the beginning of the museum retrospective like the host at the party, and sometimes at the end in farewell (in which respect, they are once again being construed as surrogates).

In any case indifference is not what Dürer’s painting invites or inspires, and this sense of agency is crucial to its power; for all its preternatural stillness, the self-portrait feels almost oppressively vital.

The self-portrait is cast as a frontispiece, a prologue before we get down to the real work, no matter that it may be among the artist’s greatest achievements, and this Dürer both courts and defies. He puts his self-portrait forward very consciously as a frontispiece but also as an unprecedented work of art. You are not to think that this is just any old painting of him so much as the defining image of Dürer the man and artist.

That he looks like Christ, that the painting resembles a frontispiece: this much is apparent all at once, but neither observation can quite explain the surpassing strangeness of the image. Strangeness is its first and last note. While there are other masterpieces of which this could be said very few of them are portraits, and still less self-portraits, which commonly have as part of their content the artist’s manifest desire to be the very opposite of strange: in fact, to be quite clearly understood.

The figure occupies a peculiar middle ground somewhere between two and three dimensions. There is no backdrop, but no foreground either and no obvious source of light. In fact, the tawny glow that illuminates the scene, beginning at the crown and rippling down through the hair, appears to emanate from Dürer’s own body. This hair, with its unnatural sheen, spreads in triangular curtains from the top of the head to the exact edge of the frame, perfectly contained as if made to measure; and the inscriptions on either side make an opposing triangle, its base the pointing finger below. These inscriptions – Dürer’s famous AD logo and the date 1500 on the left; the details of name and place on the right – are not written on any depicted surface but that of the picture itself, as part of its symmetrical composition; pendant as the scales of justice, they weigh Dürer’s face in the balance. Nothing is allowed to detract from this sense of order, geometry and design, of very close and insistent frontality. All is congruent. The artist is perfectly fused with his picture.

Dürer does not turn, he does not move, he is not looking out at you from any given time or place. He is simply and starkly himself – self-portraiture at its least equivocal – and yet he is also somebody else.