По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

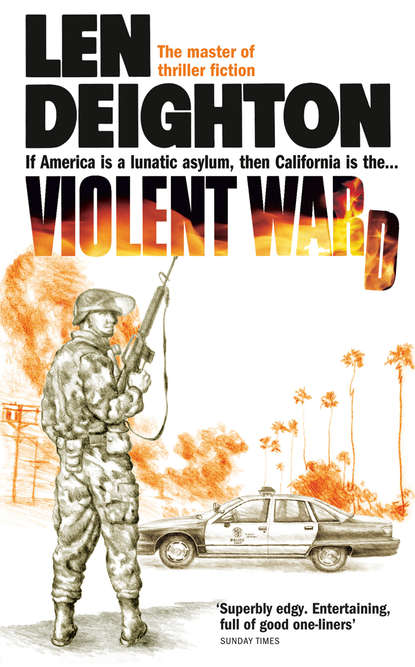

Violent Ward

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Can you beat that?’ I said, but oh, boy, I could well believe it. The two dumb jerks doing my garden knew as much about gardening as they knew about nuclear physics, and they were charging me an arm and a leg. They popped in for ten minutes of grass-cutting every Friday morning and didn’t even take the clippings and leaves away afterward. I tried to remember exactly where Cindy lived. I had driven her back there a million times. Next-door neighbor, eh? I mean: how much could they be paying him at Northrop?

‘I’ve been waiting for you to look in, Mr Murphy; you can settle a bet for me. It was Frank Loesser wrote ‘Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?’ Wasn’t it? I was arguing with my young brother; he thinks he knows everything. Back me up, will you? I’ve got ten dollars riding on it.’

‘Too bad. You lost your money, Cindy. Words by Yip Harburg, music by Jay Gorney.’

She didn’t seem too devastated at losing her ten bucks. She shook her head in admiration. ‘He should go on one of those TV quiz shows,’ she told Goldie. Goldie nodded. She had an exaggerated respect for anything she perceived as education.

I dredged my memory: ‘Written for a show called Americana sometime in the early thirties.’

Cindy refilled my coffee cup. ‘I can’t remember a darn thing these days,’ she admitted cheerfully. ‘I keep forgetting to tell you about your car, Mr Murphy.’ She poured coffee for the guys at the next table and then came back to me. ‘Maybe somebody else told you already. That old car of yours, it’s dripping oil everywhere.’

‘I know; it’s nothing,’ I said.

‘I noticed it when you drove away last week. A big pool of oil.’

‘It’s nothing that matters,’ I said. ‘Probably a gasket.’

‘Why don’t you get yourself a nice new car? Now your company has been bought out and everything.’

‘Are you crazy?’ I said. ‘That’s a valuable vintage car.’

‘Those Japanese cars are very reliable. My grandson has one. He’s got a great deal: ninety-nine dollars a month. It’s a lovely little car. Bright green. Four doors, radio, and everything. So comfortable and reliable.’ Goldie was looking at me with a stupid smile on his face.

‘And I haven’t been bought out.’ Maybe I said it too loudly.

‘I didn’t mean anything.’ She poured coffee for me.

‘Everybody keeps telling me I’m rich, except I don’t get the dough. So don’t go around saying I’ve been bought out.’

She looked at me and at Goldie and nodded. I could see what she was thinking. She was thinking I was making millions of dollars and hiding it away somewhere. ‘I thought I’d better tell you about the oil,’ she said, and walked away.

‘Stupid woman,’ I told Goldie. ‘Japanese cars. I don’t want to hear about Japanese cars.’

Goldie said, ‘Did you bring everything?’

‘I brought everything,’ I said. Goldie nodded.

I devoured the whole breakfast and even wiped the plate with bread. Was it a sign of nerves? I always eat too much when I’m tense. I wish I was one of these skinny joes who go off food when they are under stress, but with me it works just the other way. Anyway, it was a delicious breakfast: cholesterol cooked just the way I like it.

Then I reached into my leather case and brought out the glove I’d found in my safe. I put it on the table. Goldie looked at it without emotion. ‘Is this yours?’ I asked him.

‘Could be. I’ve got one just like it at home.’

‘You son of a bitch.’

‘Now we’re quits,’ said Goldie. ‘Don’t fool with my phones in future.’ He raised those heavy-lidded eyes of his to look at me.

‘I didn’t plant that bomb, Goldie.’

‘You just happened to want to make a call? You just happened to notice the wiring? Is that it?’

‘Of course it is. I didn’t plant that bomb.’

‘Maybe not, but I think you know who did. And you made sure I found it. I get the message, Mickey. Is this something you dreamed up with Budd Byron?’

‘What’s Budd got to do with it?’

‘He’s the one you promised to get a gun for, remember?’

‘This is too much! Are you bugging my office?’

‘It’s not your office any longer. You work for us now.’

I got to my feet and put some money on the table. Goldie reached out and grabbed my arm. ‘These are big boys, Mickey. This isn’t a Monopoly game, it’s real life. Ask yourself, pal. When big corporations are pushing hundreds of millions of dollars around the board, they are not deterred by some little guy reading aloud the instructions on the box lid.’ He looked at me. ‘They’ll squash you like a bug.’

‘Keep your guys out of my house,’ I said. I pulled away from his grip, picked up the glove, and tossed it at him. ‘You pull a routine like that again, and I’ll fix you in a way you won’t like.’

‘Turn off at the water tower,’ said Goldie. ‘It’s a white limo with tinted glass, parked near the main hangar.’

Camarillo airport is a onetime military field with six thousand feet of concrete runway, one hundred and fifty feet wide, and that’s more than enough to land Petrovitch’s plane even if old Petey himself is at the yoke nursing a hangover. I knew the field. For years, when driving on Route 101, I’d stolen a glance at the old blue-and-white Lockheed Constellation that marked the end of the runway.

I recognized the freeway exit ramp. I used to take Danny up that way to buy strawberries. Danny loved strawberries. I remember the first time he saw the strawberry fields – miles of them all the way to mountains – he could scarcely believe it was all real. Betty liked them too. We regularly bought berries there and took along a big tub of ice cream and had a feast in the car.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: