По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

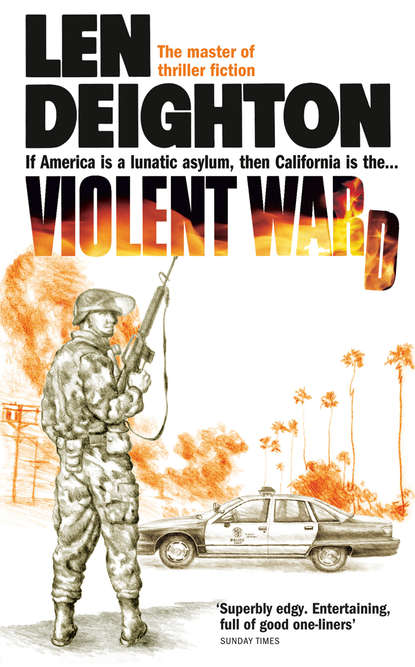

Violent Ward

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Say an extra prayer when you go to mass tomorrow morning,’ said Goldie. He was still under the desk fiddling with the bomb. ‘Go back downstairs and circulate. I can deal with this.’

‘Are you sure you don’t want the bomb squad?’

His glowering face appeared above the desktop. ‘Not a word about this to anyone, Mickey. If a story like this got into the papers, the shares would take a beating and I’d pay for it with my job.’

‘Whatever you say.’ I decided to leave my call to Phoenix for some other time and went back to the party for another drink. I could see why Goldie was so jumpy about publicity. The media crowd was well in evidence. Some of them I recognized, including two local TV announcers: the guy with the neat mustachio who does the morning show and the little girl with the elaborate hairdo who stands in for the weatherman on the local segment of the network news. They were standing near their cameras, paper napkins tucked into their collars like ruffs and their faces caked with makeup.

The one I was looking around for was Mrs Petrovitch. When I knew her we were both at Alhambra High, struggling with high school mathematics and preparing for college. High school friends are special, right? More special than any other kind of friends. In those days she was Ingrid Ibsen. I was in love with her. Half the other kids were in love with her too, but I dated her on account of the way she lived near me and I could always walk her home, and her dad knew my dad and did his accounts.

She lived only a block from me on Grenada. We used to walk down Main Street together, get a Coke and fries, and I’d think of something I had to buy in the five-and-dime just to make it last longer.

In my last year Ingrid was the lead in the senior play and I had a tap dance solo in the all-school production of The Music Man. I remember that final night: I danced real well. It was my last day of high school. It was a clear night with lots of stars and a big moon so you could see the San Gabriel Mountains. Dad let me have the new Buick. We were parked outside her house. I’d got my scholarship and a place at USC. I told her that as soon as I graduated I was going to come back and marry her. She laughed and said, ‘Don’t promise’ and put her finger on my lips. I always remembered the way she said that: ‘Don’t promise.’

Ingrid spent only one semester at college. She was smarter than I was at most subjects, and she could have got a B.A. easily, but her folks packed up and went to live in Chicago and she went with them. I never did get the full story, but the night she told me she was going, we walked around the neighborhood and I didn’t go home to bed until it was getting light. Then I had a fight with my folks, and the following day I stormed off and joined the Marine Corps. Kidlike, I figured I’d have to go to ’Nam eventually and it was better to get it over with. Now I’ve learned to put the bad ones at the bottom of the pile and hope they never show up. It was a crazy move because I was looking forward to going to college and almost never had arguments with my folks. And anyway, what does joining the service do to solve anything? It just gives you a million new and terrible problems to add to your old ones.

The next I heard of Ingrid was when her photo was in the paper. Budd Byron, who’d known us both at Alhambra, sent me an article that had been clipped from some small-town paper. It was a photo of Ingrid getting married. That was her first husband, some jerk from the sticks, long before she got hitched to Zachary Petrovitch. It said they’d met at a country dancing class. I ask you! I kept the clipping in my billfold for months. They were going to Cape Cod for their honeymoon, it said. Can you imagine anything more corny? Every time I looked at that picture it made me feel sorry for myself.

Soon after I met Betty, I ceremonially burned that clipping. As the ashes curled over and shimmered in the flames I felt liberated. The next day I went down to Saturn and Sun, the alternative medicine pharmacy where Betty worked, and asked her to marry me. As a futile exercise in self-punishment it sure beat joining the Marine Corps.

Then in the eighties I heard about Ingrid again when she upped and married Petrovitch. I knew the Petrovitch family by name; I’d even met Zach Petrovitch a few times. His father had made money from Honda dealerships in the Northwest, getting into them when they were giving them away, a time when everyone was saying the Japanese can maybe make cheap transistor radios, and motor bikes even, but cars?

The first time I met Petrovitch Junior he was with his father, who was guest of honor at an Irish orphanage’s charity dinner in New York. I guess that was before he knew Ingrid. At the end of the evening a few of us, including Zach, cut away to a bar in the Village. The music was great, and we all sank a lot of Irish whiskey. Petrovitch passed out in the toilet and we had a lot of trouble getting him back to the Stanhope, where he was staying. Cabs are leery of stopping for a group of men carrying a ‘corpse,’ and the ones that do stop, argue. I got into a fist fight with a cabbie from County Cork; it wasn’t serious, just an amiable bout with an overweight driver who wanted to stretch his legs. When I told him we were coming from the Irish orphanage benefit, he took us to the hotel and wouldn’t accept the fare money. The crazy thing was that when Petrovitch recovered someone told him I’d strong-armed the cabbie to take him that night. I suppose Petrovitch felt he owed me something. I never did explain it to him.

I moved over to the bar to sneak a look at Ingrid. She was standing with her husband at the end of the red carpet, welcoming guests as they arrived. I studied her through the palm tree fronds, making sure she didn’t see me. She looked as beautiful as ever. Her hair was still very blonde, almost white, but cut shorter now. She had on a long black moiré dress with black embroidery on the bodice and around the hem. With it she wore a gold necklace and a fancy little wrist-watch. I watched her laughing with an eager group of sharp-suited yuppies who were shaking paws with her husband. Seeing her laugh reawakened every terrible pang of losing her. It brought back that night sitting in the Buick when the idea of being married was something I didn’t have to promise. To hear that laugh every day; I would have sold my soul for that. So you can see why I didn’t go across to say hello to them. I didn’t want to be shoulder to shoulder with those jerks when talking with her. It was better to see her from a distance and shuffle through my memories.

‘Hello, Mickey. I thought you might be here,’ chirruped the kind of British accent that sounds like running your fingernails across a blackboard. I turned to see a little British lawyer named Victor Crichton. He was about forty, with the cultivated look that comes with having a company that picks up the tab for everything. His suit was perfect, his face was tanned, and his hair wavy and long enough to hide the tops of his ears.

‘Oh, it’s you,’ I said, in my usual suave and sophisticated way. Vic Crichton’s boss was Sir Jeremy Westbridge, the client who was giving me ulcers. His affairs were in such desperate disarray that I could hardly bear to open my mail in the morning.

‘Did I make you jump, old chap? Awfully sorry.’ He’d caught me off guard; I suppose I looked startled. He gave a big smile and then reached out for the arm of the woman at his side. ‘This is Dorothy, the light of my life, the woman who holds the keys to my confidential files.’ He hiccuped softly. ‘Figuratively speaking.’

I said, ‘That’s okay, Victor. Hi there, Dorothy. I was just thinking.’

‘Wow! Don’t let me interrupt anything like that!’ He winked at the woman he was with and said, ‘Mickey is Sir Jeremy’s attorney on the West Coast.’

‘Pleased to meet you,’ she said. His wife was British too.

‘It sounds good the way you say it, Vic. But we’ve got to talk.’ I was hoping to make him realize the danger he was in. It wasn’t just a matter of business acumen, they were going to be facing charges of fraud and God knows what else.

‘He’s really an Irish stand-up comic,’ Vic explained to the woman, ‘but you have to set a comic to catch a comic in this part of the world. Right, Mickey?’

‘I’ve got to talk to you, Vic,’ I said quietly. ‘Is Sir Jeremy here? We’ve got to do something urgently.’

He made no response to this warning. ‘Always together. Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Lennon and McCartney, Vic Crichton and Sir Jeremy. Partners.’

‘They all broke up,’ I said.

‘I wondered if you’d spot that,’ said Vic. ‘Split up or dead. But not us; not yet, anyway. Look for yourself.’

He waved a hand in the direction of the bar, where I spotted the lean and hungry-looking Sir Jeremy. He was a noticeable figure: very tall, well over six feet, with white hair and a pinched face. He was engaged in earnest conversation with a famous local character called the Reverend Dr Rainbow Stojil, a high-profile do-gooder for vagrants who liked to be seen on TV and at parties like this. I guessed that Stojil was trying to get a donation from him. Stojil was famous for his money-raising activities.

‘Don’t interrupt them,’ advised Vic.

‘Why not?’ I said. ‘We’ve got to have a meeting.’ Vic didn’t reply. He was drunk. I wasn’t really expecting a sensible answer.

Vic and his master were well matched. They were as crooked as you can get without ski masks and sawed-off shotguns. They called themselves property developers. Their cemeteries became golf courses; their golf courses became leisure centers, and leisure centers became shopping malls and offices. They had moved slowly and legally at first but success seemed to affect their brains, because lately they just didn’t care what laws they broke as long as the cash came rolling in.

‘Look,’ I said. ‘The game’s up with all this shit. I know for a fact that an investigation has begun. It’s just a matter of time before Sir Jeremy is arrested. I can’t hold them off forever.’

‘How long can you hold them off, old boy?’

He wasn’t taking me seriously. ‘I don’t know, not long. One, two, three weeks … it’s difficult to say.’

He prodded me in the chest. ‘Make it three weeks, old buddy.’ He laughed.

‘Look, Vic, either we sit down and talk and make a plan that I can offer to them—’

‘Or what?’ he said threateningly.

I took a deep breath. ‘Or you can get yourselves a new lawyer.’

He blinked. ‘Now, now, Mickey. Calm down.’

‘I mean it. You find yourself a new boy. Some guy who likes fighting the feds and the whole slew of people you’ve crossed. A trial lawyer.’

‘If that’s the way you feel, old boy,’ he said and touched me on the shoulder in that confident way that trainers pat a rottweiler.

Maybe he thought I was going to retract, but he was wrong. With that decision made, I already felt a lot better. ‘I’ll get all the papers and everything together. You tell me who to pass it to. How long are you staying in town?’

‘Not long.’ He held up his champagne and inspected it as if for the Food and Drug Administration. ‘We’ve come to hold hands with Petrovitch about a joint company we’re forming in Peru. Then I’m off for a dodgy little argument with some bankers in Nassau and back to London for Friday. Around the world in eight hotel beds: it’s all go, isn’t it, Dot?’

‘What about Sir Jeremy?’

‘Good question, old man. Let’s just say he has a date with Destiny. He’s modeling extra-large shrouds for Old Nick.’ He held out a hand to the wall to steady himself. Any minute now he was going to fall over.

‘What do you mean?’ I said, watching his attempt to regain equilibrium.

‘Don’t overdo it, old sport.’ He put his arm around my shoulder and leaned his head close to whisper. ‘You don’t have to play the innocent with me. I’m the next one to go.’

‘Go where?’

‘You are the one arranging it, aren’t you?’ His amiable mood was changing to irritation, as is the way with drunks when they become incoherent. ‘You buggers are being paid to fix it.’ He closed his eyes as if concentrating his thoughts. His lips moved but the promised words never came.

‘I think we’re boring your wife, Victor,’ I said, in response to the flamboyant way she was patting her open mouth with her little white hand.

‘Victor always gets drunk,’ she said philosophically. She didn’t look so sober herself. She’d drained her champagne and experimentally pushed the empty glass into a palm tree and left it balanced miraculously between the fronds.

Victor didn’t deny his condition. ‘Banjaxed, bombed, bug-eyed, and bingoed,’ he said without slurring his words. ‘Wonderful town, lavish hospitality, and vintage champagne. Very rare nowadays …’ He drawled to a stop like a clockwork toy that needed rewinding.