По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

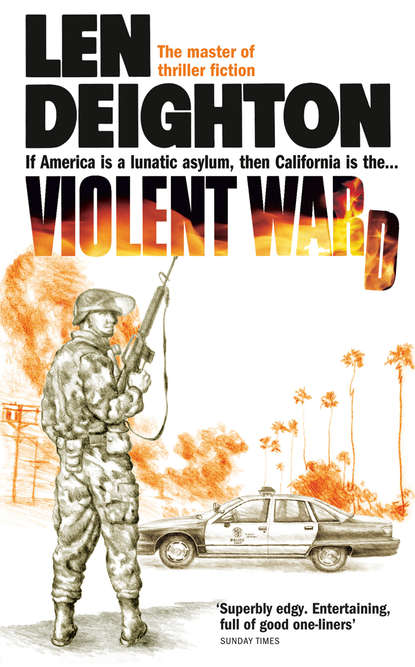

Violent Ward

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He looked up.

I said, ‘Are you doing her accounts or something? Why doesn’t she get a paying job?’

‘The aroma therapy workshop is a charity. It’s for poor people. No one pays. She wants to help people.’

‘She wants to help people? She works for nothing and I give her money. How does that make her the one who helps people?’

‘She’s really a wonderful person, Dad. I wish you’d make a little more effort to try and understand her.’

‘It’s always my fault. Why doesn’t she make an effort to try and understand me?’

‘She said you’re getting millions from the takeover.’

‘You two live in a dream world. There are no millions and there is no takeover. You can’t buy a law partnership unless you are a member of the California bar. Petrovitch picked up the pieces, that’s all that happened. He simply retained our services, put in a partner, and absorbed nearly a quarter of a million dollars of debt. I told you all that.’

‘She clipped a piece about Zach Petrovitch from the Los Angeles Times Business Section. It said in there that he’d paid a hundred million—’

‘But not for my partnership. I’ve heard all that talk. He picked up a Chapter Eleven recording company with a few big names on the labels and sold it to the Japanese. That all happened nearly three years ago. There’s been a goddamned recession since then.’

‘Petrovitch only buys companies he has plans for.’

‘Is this something they tell you in Philosophy One-oh-one, or did you switch to being a business major?’

‘You can’t keep that kind of pay off secret, Dad,’ he said. ‘Everyone knows.’

‘Don’t give me that shit, Danny. I’m your father, and I’m telling you all we got is a retainer with a small advance so I can pay off a few pressing debts. Who are you going to believe?’

‘You want a beer?’ He got up and went into the kitchen.

‘You haven’t answered the question,’ I called. ‘No. I don’t want a beer, and you’re too young to drink beer.’

‘I thought it was a rhetorical question,’ he called mournfully from the kitchen. I heard him rattling through the cans; I don’t think he’d ever thought of storing food in that icebox, just drink. ‘I’ve got Pepsi and Diet Pepsi; I’ve got Sprite, Dr Pepper, and all kinds of fruit juices.’

‘I don’t want anything to drink. Come back here and listen to me. I’m not a philosophy major; I haven’t got time to sit around talking for hours. I have to work for a living.’

I found a cane-seat chair and inspected it for food remains and parked chewing gum before sitting down. This was just the kind of chaos he’d lived in at home, like someone had thrown a concussion grenade into a Mexican fast-food counter. On the walls there were colored posters about saving the rain forest and protecting the whales. The only valuable item to be seen in the apartment was the zillion-watt amplifier that had made sure his guitar was shaking wax out of ears in Long Beach while he strummed it in Woodland Hills. Near the window there was a small table he used as a desk. There was a pile of philosophy books, an ancient laptop computer with labels stuck all over it, and a paper plate from which bright red sauce had been scraped. There was a brown bag too, the kind of insulated bag take-away counters use for hot food. I looked into it, expecting to find a tamale or a hot dog, but found myself looking at a stainless steel sandwich.

‘What’s this?’ I said.

Danny came out of the kitchen with his can of drink and a package of non-cholesterol chili-flavored potato chips. ‘It’s only a gun,’ he said.

‘Oh, it’s only a gun,’ I said sarcastically, bringing it out to take a closer look at it.

It was a shiny new Browning Model 35 9-mm automatic. I pulled back the action to make sure there were no rounds in the chamber. The action remained open, and from the pristine orange-colored top of the spring I could see it was brand new.

‘And what the hell are you doing with this?’ I took aim at Robyna’s save the whale poster and pulled the trigger a couple of times.

‘Relax, Dad. I loaned a Jordanian guy in my religion class two hundred bucks. He was strapped, and instead of paying me back he gave me the shooter and a stereo.’

‘You were ripped off,’ I said.

‘You’re always so suspicious,’ he said mildly. ‘A gun like that costs about five hundred bucks. I can pawn it for three hundred.’

‘How do you know it’s not been used in a stickup or a murder?’

‘His father had just bought it for him; it was still in the wrappings. So was the stereo.’

‘His father bought it? What kind of dope is his father?’

‘Don’t keep doing that, Dad. It’s not good for the mechanism.’

‘What do you know about guns?’ I said and pulled out the magazine and snapped it back into place a couple more times just to show him I wasn’t taking orders from him. ‘You’re talking to a marine, remember. Have you ever fired this gun?’

‘No, I haven’t.’

‘Budd Byron was in the office today asking me how he could buy a gun. This whole town is gun crazy these days.’

‘What does he want a gun for?’

‘Budd? I don’t know.’ I looked at the gun. It was factory-new. ‘In the original wrappings, you say? In the box? Then this is part of a stolen consignment.’

‘It’s not stolen. I just told you I got it from a guy I know at college. He does Comparative Religion with me. Next week he’ll probably want to buy it all back. He’s like that. He’s an Arab; he’s a distant relative of Kashoggi the billionaire.’

‘Do you know something? I’m still looking for some Arab in this town who is not a relative of Kashoggi. My mailman mentioned that he is Kashoggi’s cousin. The guy in the cleaners confided that he is Kashoggi’s nephew. They’re all just one big happy family.’

The TV was still muttering away: the ads are always louder than the programs. ‘You’re in a crumby mood today, Dad. Did something bad happen to you?’

‘Something bad? Have you suddenly gone deaf or something? Your mother dropped by to throw herself out of my office window.’

‘That was just a cry for help. You know that.’ He ate some chips, crunching them loudly in his teeth; then, leaning his head far back, he closed his eyes and held a cold can of low-cal cranberry juice cocktail to his forehead.

He wouldn’t hear a word against Betty. Sometimes I wondered if he understood that she walked out on me – walked out on us, rather. Yet how could I remind him of that? I said, ‘Will you find out where your mother is crashing these days? If she keeps pulling these jumping-off-the-ledge routines, she’ll get herself committed.’

He came awake, snapped the top off his cranberry juice, and took a deep gulp. He wiped his lips on the back of his hand and said, ‘Yah, okay, Dad. I’ll do what I can.’

‘Tell her I’ll maybe look at her dentist bills. I’ll pay something toward them.’

‘Hey, that’s great, Dad.’

‘I don’t want you getting together with her and rewriting the accounts, trying to bill me for a Chanel suit or something.’

‘What do you mean?’ Danny said.

‘You know what I mean. Do you think I’ve forgotten you using the graphics program on my office IBM to do that CIA letterhead that scared the bejesus out of old Mr Southgate?’

‘He deserved it. I should have gotten an A in his English class. Everyone said so.’

‘Well, I had to calm him down and stop him from writing to his senator. You promised you’d be sensible in future, so leave it between Betty and her dentist, will you?’