По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

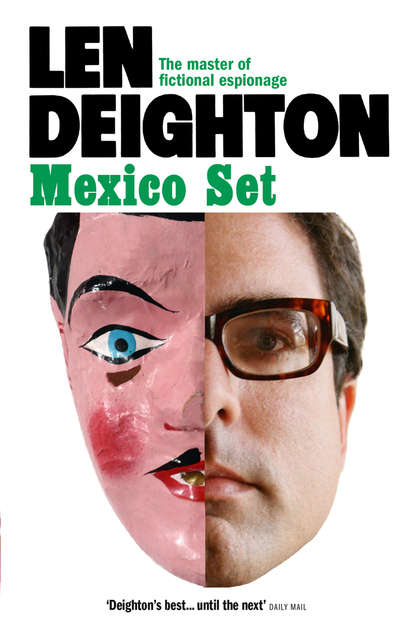

Mexico Set

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Len Deighton (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#u9c0e2a0f-d19c-58b3-a995-31eaa329af39)

During the First World War the neutral Netherlands had been the arena in which the rival spy services brawled. In the Second World War it was Portugal that served that purpose. In the Cold War the arena eventually became Mexico. It was in safe houses in Mexico City where the officers of the GRU and those of the KGB clashed, reasoned or sometimes socialized with their Allied opposite numbers. For Moscow, Washington and London these contacts were vital, but for the personnel stationed there the job was a consignment to the promotional rubbish heap. No interesting memoirs were written by the men who spent the Cold War years in Mexico. No indiscreet revelations were spilled into the well-paid serializations that sold the newspapers of that time. Mexico City only came into the headlines as a stopover for Lee Harvey Oswald when the assassination of President John Kennedy was being investigated.

The very first time I visited Mexico I was staying at the YMCA in Los Angeles. I was a penniless art student; well, perhaps that overstates it: let’s say I was living from hand to mouth and being saved from starvation by the care and consideration given me by the mother of an American artist I knew in London. Left to my own devices on my last day I ate supper from a hot-dog stand. Los Angeles was not the gourmet’s paradise that it later became, and street food was America’s answer to the fugu fish. I spent the night groaning in the toilets and when daylight finally arrived I was feeling very ill. In my pocket I had a Greyhound Bus ticket that would take me a few hundred miles into a country I knew nothing about and, with that physical stamina and grim determination that is the currency of the young and foolish, I dragged myself down to the bus depot, threw myself across the back seat and closed my eyes. You may wish to note that the back seat of a Greyhound Bus is not the best place to be if you are alternately praying for help and wishing to die. The sort of buses that are built for Mexico are fitted with robust and unyielding suspensions. The rearmost part of the chassis takes an undue proportion of the punishment that comes with loose surface roads and pot-holes. I recall every jolt of that journey but towards the end of it I was sitting upright and looking out of the window trying to see through the grime and the dust. As always, the Greyhound Bus got me there. During the nineteen fifties I did so many thousands of miles on Grey Buses that they used me in their advertising.

I survived the journey. I climbed down from the bus into the sweaty noon of Mexico’s west coast, spotted a bench and a Coca Cola stand and I started writing some notes for my diary. I’m told that nowadays this region of Mexico is packed with luxury hotels, motor-yachts and marinas but back in the nineteen fifties it was just a succession of small villages punctuating empty stretches of bleak, cactus strewn landscape. But the traveller counting the pennies gets a far more authentic impression of a country than any luxury tour can provide. The Mexicans were kind and generous to me and, if the steady diet of beans and tortillas I ate became monotonous, I knew that was only because I wasn’t as hungry as those around me. I felt at home. From that time I have always enjoyed being with Mexicans, and nowadays I am delighted to have become a part of a kind and joyful Mexican family.

I have always contrived to visit places at their least attractive time. Ski resorts in high summer, Asia when the monsoons come, Algeria in the annual rainstorms and the French Riviera when the restaurants are shuttered and the casinos being renovated. It may sound perverse but I can only get under the skin of foreign destinations when the lipstick and powder has been set aside and the spots and pimples are there for all to see. So, when I researched Mexico Set I saw it in the stormy season when the steely thunderclouds reach down lower and lower upon the thirsty earth until torrential rain arrives to lash the streets with fury.

Mexico Set opens with Bernard Samson and Dicky Cruyer in Mexico City. For Bernard the problems are piling higher and higher. While Berlin Game saw Bernard battered by professional dilemmas we now see the complex uncertainties of his private life. In this book I am able to do a few of the things that made the whole nine-book project so worthwhile for me. Instead of going back to start all over again with a new story I could take my characters deeper and deeper into the lives that, while being so weird and wonderful, are burdened with the domestic everyday events that we all endure.

Every writer wants to maximize everything: intriguing characters, labyrinthine plot, humorous asides, unfolding landscape, crisp dialogue. But now I didn’t have to cram all that tightly together; having the space granted by the planned future books gave me a freedom to do something better than I had ever done before. Of course every story worth reading has all of the above. Berlin Game with its dénouement set the scene. After that Mexico Set used arguments, anger and confidences to reveal new sides of the characters and their shifting attitudes to each other. Many important characters arrive in subsequent volumes but by the end of this book all the stars are on the stage. Yet in this book – and I know this is going to sound corny – Mexico is the star. It is a wonderful country, its cruel landscape tormented by its amazing weather patterns. With the ever-present danger of ending up writing a travel guide dominated by weather reports, I have kept Mexico as a persistent backdrop to the story of Bernard Samson.

Are the stories based on real people? Scott Fitzgerald argued with Ernest Hemingway about the nature of fiction. Writing to a friend who was deeply offended by the way she was depicted in his book, Fitzgerald said: ‘In my theory, utterly opposite to Ernest’s, about fiction i.e. that it takes half a dozen people to make a synthesis strong enough to create a fiction character – in that theory, or rather in despite of it, I used you again and again in Tender [is the Night].’ And so it is that most writers take manners and gestures and other bits and pieces from the people they meet, they steal slices from the landscape, relive the pain and joy of their experience. In this way the writer pushes beyond reality in pursuit of some sort of truth.

Len Deighton, 2010

1 (#u9c0e2a0f-d19c-58b3-a995-31eaa329af39)

‘Some of these people want to get killed,’ said Dicky Cruyer, as he jabbed the brake pedal to avoid hitting a newsboy. The kid grinned as he slid between the slowly moving cars, flourishing his newspapers with the controlled abandon of a fan dancer. ‘Six Face Firing Squad’; the headlines were huge and shiny black. ‘Hurricane Threatens Veracruz.’ A smudgy photo of street fighting in San Salvador covered the whole front of a tabloid.

It was late afternoon. The streets shone with that curiously bright shadowless light that precedes a storm. All six lanes of traffic crawling along the Insurgentes halted, and more newsboys danced into the road, together with a woman selling flowers and a kid with lottery tickets trailing from a roll like toilet paper.

Picking his way between the cars came a handsome man in old jeans and checked shirt. He was accompanied by a small child. The man had a Coca Cola bottle in his fist. He swigged at it and then tilted his head back again, looking up into the heavens. He stood erect and immobile, like a bronze statue, before igniting his breath so that a great ball of fire burst from his mouth.

‘Bloody hell!’ said Dicky. ‘That’s dangerous.’

‘It’s a living,’ I said. I’d seen the fire-eaters before. There was always one of them performing somewhere in the big traffic jams. I switched on the car radio but electricity in the air blotted out the music with the sounds of static. It was very hot. I opened the window but the sudden stink of diesel fumes made me close it again. I held my hand against the air-conditioning outlet but the air was warm.

Again the fire-eater blew a huge orange balloon of flame into the air.

‘For us,’ explained Dicky. ‘Dangerous for people in the cars. Flames like that, with all these petrol fumes … can you imagine?’ There was a slow roll of thunder. ‘If only it would rain,’ said Dicky. I looked at the sky, the low black clouds trimmed with gold. The huge sun was coloured bright red by the city’s ever-present blanket of smog, and squeezed tight between the glass buildings that dripped with its light.

‘Who got this car for us?’ I said. A motorcycle, its pillion piled high with cases of beer, weaved precariously between the cars, narrowly missing the flower seller.

‘One of the embassy people,’ said Dicky. He released the brake and the big blue Chevrolet rolled forward a few feet and then all the traffic stopped again. In any town north of the border this factory-fresh car would not have drawn a second glance. But Mexico City is the place old cars go to die. Most of those around us were dented and rusty, or they were crudely repainted in bright primary colours. ‘A friend of mine lent it to us.’

‘I might have guessed,’ I said.

‘It was short notice. They didn’t know we were coming until the day before yesterday. Henry Tiptree – the one who met us at the airport – let us have it. It was a special favour because I knew him at Oxford.’

‘I wish you hadn’t known him at Oxford; then we could have rented one from Hertz – with air-conditioning that worked.’

‘So what can we do …’ said Dicky irritably ‘… take it back and tell him it’s not good enough for us?’

We watched the fire-eater blow another balloon of flame while the small boy hurried from driver to driver, collecting a peso here and there for his father’s performance.

Dicky took some Mexican coins from the slash pocket of his denim jacket and gave them to the child. It was Dicky’s faded work suit, his cowboy boots and curly hair that had attracted the attention of the tough-looking woman immigration officer at Mexico City airport. It was only the first-class labels on his expensive baggage, and the fast talking of Dicky’s Counsellor friend from the embassy, that saved him from the indignity of a body search.

Dicky Cruyer was a curious mixture of scholarship and ruthless ambition, but he was insensitive, and this was often his undoing. His insensitivity to people, place and atmosphere could make him seem a clown instead of the cool sophisticate that was his own image of himself. But that didn’t make him any less terrifying as friend or foe.

The flower seller bent down, tapped on the window glass and waved at Dicky. He shouted ‘Vamos!’ It was almost impossible to see her face behind the unwieldy armful of flowers. Here were blossoms of all colours, shapes and sizes. Flowers for weddings and flowers for dinner hostesses, flowers for mistresses and flowers for suspicious wives.

The traffic began moving again. Dicky shouted ‘Vamos!’ much louder.

The woman saw me reaching into my pocket for money and separated a dozen long-stemmed pink roses from the less expensive marigolds and asters. ‘Maybe some flowers would be something to give to Werner’s wife,’ I said.

Dicky ignored my suggestion. ‘Get out of the way,’ he shouted at the old woman, and the car leaped forward. The old woman jumped clear.

‘Take it easy, Dicky, you nearly knocked her over.’

‘Vamos! I told her; vamos. They shouldn’t be in the road. Are they all crazy? She heard me all right.’

‘Vamos means “Okay, let’s go”,’ I said. ‘She thought you wanted to buy some.’

‘In Mexico it also means scram,’ said Dicky driving up close to a white VW bus in front of us. It was full of people and boxes of tomatoes, and its dented bodywork was caked with mud in the way that cars become when they venture on to country roads at this rainy time of year. Its exhaust-pipe was newly bound up with wire, and the rear panel had been removed to help cool the engine. The sound of its fan made a very loud whine so that Dicky had to speak loudly to make himself heard. ‘Vamos; scram. They say it in cowboy films.’