По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

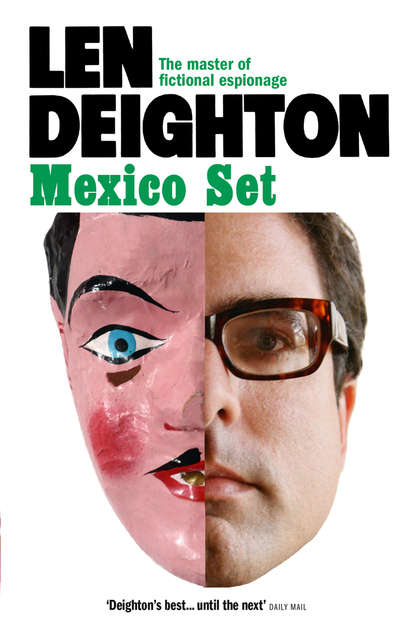

Mexico Set

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What will happen now?’ said Zena. She was short; she only came up to Dicky’s shoulder. Some say short people are aggressive to compensate for their small stature, but look at Zena Volkmann and you might start thinking that aggressive people are made short lest they take over the whole world. Either way Zena was short and the aggression inside her was always bubbling along the edges of the pan like milk before it boils over. ‘What will you do about him?’

‘Don’t ask,’ Werner told her.

But Dicky answered her, ‘We want to talk to him, Mrs Volkmann. No rough stuff, if that’s what you are afraid of.’

I swallowed my fruit punch and got a mouthful of tiny pieces of ice and some lemon pips.

Zena smiled. She wasn’t frightened of any rough stuff; she was frightened of not getting the money for arranging it. She stood up and twisted her shoulders, slowly stretching her arms above her head one after the other in a lazy display of overt sexuality. ‘Do you want my help?’ she said.

Dicky didn’t answer directly. He looked from Zena to Werner and back again and said, ‘Stinnes is a KGB major. That’s too low a rank for the computer to offer much on him. Most of what we know about him came from Bernard, who was interrogated by him.’ A glance at me to stress the unreliability of uncorroborated intelligence from any source. ‘But he’s senior staff in Berlin. So what is he doing in Mexico? Must be a Russian national. What’s his game? What’s he doing in this German club of yours?’

Zena laughed. ‘You think he should have joined Perovsky’s?’ She laughed again.

Werner said, ‘Zena knows this town very well, Dicky. She has aunts and uncles, cousins and a nephew here. She lived here for six months when she first left school.’

‘Where, what, how or why is Perovsky’s?’ said Dicky. He was German Stations Controller. He didn’t like being laughed at, and I could see he was taking a little time getting used to Werner calling him Dicky.

‘Zena is joking,’ explained Werner. ‘Perovsky’s is a big, rather run-down club for Russians near the National Palace. The ground floor is a restaurant open to anyone. It was started after the revolution. The members used to be dukes and counts and people who’d escaped from the Bolsheviks. Now it’s a pretty mixed crowd but the anti-communist line is still de rigueur. The people from the Soviet Embassy give it a wide berth. If a man such as Stinnes went in there and spoke out of turn he might never get out.’

‘Really never get out?’ I said.

Werner turned to look at me. ‘It’s a rough town, Bernie. It’s not all margaritas and mariachis like the travel posters.’

‘But the Kronprinz Club is not so particular about its membership?’ persisted Dicky.

‘No one goes there to talk politics. It’s the only place in town where you can get real German draught beer and good German food,’ explained Werner. ‘It’s very popular. It’s a social club; you get a very mixed crowd there. A lot of them are transients: airline pilots, salesmen, ships’ engineers, businessmen, priests even.’

‘And KGB men?’

‘You Englishmen avoid each other when you are abroad,’ said Werner. ‘We Germans like to be together. East Germans, West Germans, exiles, expatriates, men avoiding tax, men avoiding their wives, men avoiding their creditors, men avoiding the police. Nazis, monarchists, communists, even Jews like me. We like to be together because we are Germans.’

‘Such Germans as Stinnes?’ said Dicky sarcastically.

‘He must have lived in Berlin. His German is as good as Bernie’s,’ said Werner, looking at me. ‘Even more convincing in a way, because he has the sort of strong Berlin accent you seldom hear except in some workers’ bar in the city. It was only when I began to listen to him really carefully that I could detect something that was not quite right in the background of his voice. I’ll bet everyone in the club thinks he’s German.’

‘He’s not here to get a tan,’ said Dicky. ‘A man like that is sent here only for something special. What’s your guess, Bernard?’

‘Stinnes was in Cuba,’ I said. ‘He told me that when we talked together. Security police. I went back to the continuity files and began to guess he was there to give the Cubans some advice when they purged some of the bigwigs in 1970. It was a big shake-up. Stinnes must have been some kind of Latin America expert even then.’

‘Never mind old history,’ said Dicky. ‘What’s he doing now?’

‘Running agents, I suppose. Guatemala is a KGB priority, and it’s not so far from here. Anyone can walk through; the border is just jungle.’

‘I don’t think that’s it,’ said Werner.

I said, ‘The East Germans backed the Sandinista National Liberation Front long before it looked like winning and forming a government.’

‘The East Germans back anybody who might be a thorn in the flesh of the Americans,’ said Werner.

‘But what do you really think he’s doing?’ Dicky asked me.

I was stalling because I didn’t know how much Dicky would want me to say in front of Zena and Werner. I kept stalling. I said, ‘Stinnes speaks good English. Unless the cheque book is a deliberate way of throwing us off the scent, he might be running agents into California. Handling data stolen from electronics and software research firms perhaps.’ I was improvising. I didn’t have the slightest idea of what Stinnes might be doing.

‘Why would London give a damn about that sort of caper?’ said Werner, who knew me well enough to guess that I was bluffing. ‘Don’t tell me London Central put out an urgent call for Stinnes because he’s stealing computer secrets from the Americans.’

‘It’s the only reason I can think of,’ I said.

‘Don’t treat me like a child, Bernard,’ said Werner. ‘If you don’t want to tell me, just say so.’

As if in response to Werner’s acrimony, Zena went across to the fireplace and pressed a hidden bellpush. From somewhere in the labyrinth of the apartment there came the sound of footsteps, and an Indian woman appeared. She had that chin-up stance that makes so many Mexicans look as if they are ready to balance a water jug on their heads, and her eyes were half closed. ‘I knew you’d want to sample some Mexican food,’ said Zena. Personally it was the last thing I’d ever want to sample, but without waiting to hear our response she told the woman we would sit down immediately. Zena used her poor Spanish with a fluent confidence that made it sound better. Zena did everything like that.

‘She can understand German perfectly and a certain amount of English too,’ said Zena after the woman had gone. It was a warning to guard our tongues. ‘Maria has worked for my aunt for over ten years.’

‘But you don’t talk to her in German,’ said Dicky.

Zena smiled at him. ‘By the time you’ve said tortillas, tacos, guacamole and quesadillas, and so on, you might as well add por favor and get it over with.’

It was an elegant table, shining with solid-silver cutlery, hand-embroidered linen and fine cut-glass. The meal had obviously been planned and prepared as part of Zena’s pitch for a cash payment. It was a good meal, and not too damned ethnic, thank God. I have a very limited capacity for the primitive permutations of tortillas, bean-mush and chillies that numb the palate and sear the insides from Dallas to Cape Horn. But we started with grilled lobster and cold white wine, and not a refried bean in sight.

The curtains were drawn back so that air could come in through the open windows, but the air was not cool. The cyclone out in the Gulf had not moved nearer the coast, so the threatened storms had not come but neither had much drop in temperature. By now the sun had gone down behind the mountains that surround the city on every side, and the sky was mauve. Pin-pointed like stars in a planetarium were the lights of the city, which stretched all the way to the foothills of the distant mountains until like a galaxy they became a milky blur. The dining room was dark; the only light came from tall candles that burned brightly in the still air.

‘Sometimes London Central can get in ahead of our American friends,’ said Dicky, suddenly spearing another grilled lobster tail. Had he really spent so long thinking up a reply for Werner? ‘It would give us negotiating power in Washington if we had some good material about KGB penetration of anywhere in Uncle Sam’s backyard.’

Werner reached across the table to pour more wine for his wife. ‘This is Chilean wine,’ said Werner. He poured some for Dicky and for me and then refilled his own glass. It was Werner’s way of telling Dicky he didn’t believe a word of it, but I’m not sure Dicky understood that.

‘It’s not bad,’ said Dicky, sipping, closing his eyes and tilting his head back to concentrate all his attention on the taste. Dicky fancied his wine expertise. He’d already made a great show of sniffing the cork. ‘I suppose, with the peso collapsing, it will be more and more difficult to get any sort of imported wine. And Mexican wine is a bit of an acquired taste.’

‘Stinnes only arrived here two or three weeks ago,’ said Werner doggedly. ‘If London Central is interested in Stinnes, it won’t be on account of anything he might be planning to do in Silicon Valley or in the Guatemala rain forest; it will be on account of all the things he did in Berlin during the last two years.’

‘Do you think so? said Dicky, looking at Werner with friendly and respectful interest, like a man who wanted to learn something. But Werner could see through him.

‘I’m not an idiot,’ said Werner, using the unemotional tone but exaggerated clarity with which a man might specify decaffeinated coffee to an inattentive waiter. ‘I was dodging KGB men when I was ten years old. Bernie and I were working for the department when the Wall was built in 1961 and you were still at school.’

‘Point taken, old boy,’ said Dicky with a smile. He could afford to smile; he was two years younger than either of us, with years’ less time in the department, but he’d got the coveted job of German Stations Controller against tough competition. And – despite rumours about an imminent reshuffle in London Central – he was still holding on to it. ‘But the fact is that the people in London don’t tell me every last thing they have in mind. I’m just the chap chipping away at the coal-face, right? They don’t consult me about building new nuclear power stations.’ He poured some warm butter over his last piece of lobster with a care that suggested he had no other concern in his mind.

‘Tell me about Stinnes,’ I said to Werner. ‘Does he come along to the Kronprinz Club trailing a string of KGB zombies? Or does he come on his own? Does he sit in the corner with his big glass of Berliner Weisse mit Schuss, or does he sniff round to see what he can ferret out? How does he behave, Werner?’

‘He’s a loner,’ said Werner. ‘He probably would never have spoken to us in the first place except that he mistook Zena for one of the Biedermann girls.’

‘Who are the Biedermann girls?’ said Dicky. After the remains of the lobster course had been removed, the Indian servant brought an elaborate array of Mexican dishes: refried beans, whole chillies and the tortilla in its various disguises: enchiladas, tacos, tostadas and quesadillas. Dicky paused for long enough to have each one identified and described but he took only a tiny portion on his plate.

‘Here in Mexico the chilli has sexual significance,’ said Zena, directing the remark to Dicky. ‘The man who eats hot chillies is thought to be virile and strong.’

‘Oh, I love chillies,’ said Dicky, his tone of voice picking up the hint of mockery that was to be detected in Zena’s remark. ‘Always have had a weakness for chillies,’ he said, as he reached for a plate on which many different ones were arranged. I glanced at Werner who was watching Dicky with interest. Dicky looked up to see Werner’s face. ‘It’s the tiny, dark-coloured ones that blow your head off,’ Dicky explained. He took a large, pale-green cayenne and smiled at our doubting faces before biting a section from it.

There was a silence after Dicky’s mouth closed upon the chilli. Everyone except Dicky knew he’d mistaken the cayenne for one of the very mild aji chillies from the eastern provinces. And soon Dicky knew it too. His face went red, his mouth half opened, and tears shone in his eyes. He fought against the pain but he had to take it from his mouth. Then he fed himself lots and lots of plain rice.

‘The Biedermanns are a wealthy Berlin family,’ said Zena, carrying on as if she’d not noticed Dicky’s desperate discomfort. ‘They are well known in Germany. They have interests in German travel companies. The newspapers said the company had borrowed millions of dollars to build a holiday village in the Yucatan peninsula. It’s never been finished. Erich Stinnes thought I looked just like the younger sister Poppy who’s always in the newspaper gossip columns.’