По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

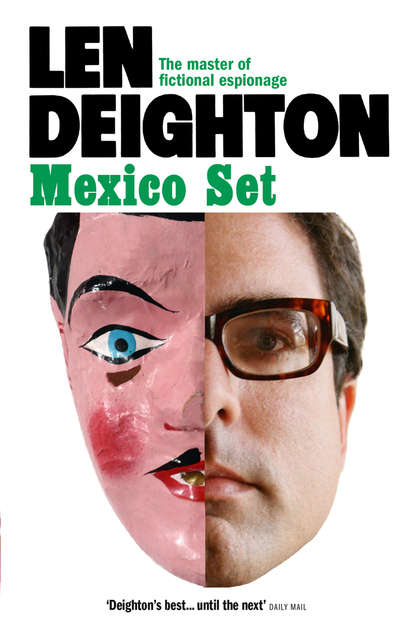

Mexico Set

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘And that’s what you’d like me to do now?’ asked Stinnes mockingly. ‘Bring our boys out to clear the streets the way we cleared them in 1945? Announce an immediate curfew and give the army shoot-on-sight orders?’

‘You know what I mean.’

‘You have no idea what this business is all about, Pavel. You’ve spent your career running typewriters; I’ve spent mine running people.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘You rush in like a rapist when we are in the middle of a seduction. Do you really think you can march agents up and down like Prussian infantry? Don’t you understand that men such as Biedermann have to be romanced?’

‘We should never use agents who are not politically dedicated to us,’ said Pavel.

Stinnes went to the window and I could see him clearly in the moonlight as he looked at the sea. Outside, the wind was roaring through the trees and making thumping noises against the windows. Stinnes held his drink up high and swirled it round to see the expensive brandy cling to the glass. ‘You’ve still got that passion that I once had,’ said Stinnes. ‘How do you hang on to all your illusions, Pavel?’

‘You’re a cynic,’ said the elder man. ‘I might as well ask how you continue doing your job without believing in it.’

‘Believing?’ said Stinnes, drinking some of the brandy and turning back to face his companion. ‘Believing what? Believing in my job or believing in the socialist revolution?’

‘You talk as if the two beliefs are incompatible.’

‘Are they compatible? Can a “workers and peasants state” need so many secret policemen like us?’

‘There is a threat from without,’ said the elder man, using the standard Party cliché.

‘Do you know what Brecht wrote after the 17th June uprising? Brecht I’m talking about, not some Western reactionary. Brecht wrote a poem called “The Solution”. Did you ever read it?’

‘I’ve no time for poetry.’

‘Brecht asked, would it not be easier for the government to dissolve the people, and vote itself another?’

‘Do you know what people say of you in Moscow?’ the older man asked. ‘They say, is this man a Russian or is he a German?’

‘And what do you say when people ask that question of you, Pavel?’

‘I had never met you,’ said the elder man, ‘I knew you only by reputation.’

‘And now? Now that you’ve met me?’

‘You like speaking German so much that sometimes I think you’ve forgotten how to speak Russian.’

‘I haven’t forgotten my mother tongue, Pavel. But it is good for you to practise German. Even more you need Spanish, but your appalling Spanish hurts my ears.’

‘You use your German name so much, I wonder if you are ashamed of your father’s name.’

‘I’m not ashamed, Pavel. Stinnes was my operational name and I have retained it. Many others have done the same.’

‘You take a German wife and I wonder if Russian girls were not good enough for you.’

‘I was on active service when I married, Pavel. There were no objections then as I remember.’

‘And now I hear you talk of the June ’53 uprising as if you sympathized with the German terrorists. What about our Russian boys whose blood was spilled restoring law and order?’

‘My loyalty is not in question, Pavel. My record is better than yours, and you know that.’

‘But you don’t believe any more.’

‘Perhaps I never did believe in the way that you believe,’ said Stinnes. ‘Perhaps that’s the answer.’

‘There’s no half-way,’ said the elder man. ‘Either you accept the Party Congress and its interpretation of Marxist-Leninism or you are a heretic.’

‘A heretic?’ said Stinnes, feigning interest. ‘Extra ecclesiam nulla salus; no salvation is possible outside the Church. Is that it, Pavel? Well, perhaps I am a heretic. And it’s your misfortune that the Party prefers that, and so does the service. A heretic like me does not lose his faith.’

‘You don’t care about the struggle,’ said the elder man. ‘You can’t even be bothered to search the house.’

‘There’s no car, and no boat at the dock. Do you think a man such as Biedermann would come on foot through the jungle that frightens you so much?’

‘You knew he wouldn’t be here.’

‘He’s a thousand miles away by now,’ said Stinnes. ‘He’s rich. A man like that can go anywhere at a moment’s notice. Perhaps you haven’t been in the West long enough to understand how difficult that makes our job.’

‘Then why did we drag ourselves out here through that disgusting jungle?’

‘You know why we came. We came because Biedermann told us the Englishman phoned and said he was coming here. We came because the stupid woman in Berlin sent a priority telex last night telling us to come here.’

‘And you wanted to prove Berlin was wrong. You wanted to prove you know better than she knows.’

‘Biedermann is a liar. We have found that over and over again.’

‘Then let’s get on the road back,’ said the older man. ‘You’ve proved your point; now let’s get back to Mexico City, back to electric light and hot water.’

‘The house must be searched. You are right, Pavel. Take a look round. I will wait here.’

‘I have no gun.’

‘If anyone kills you, Pavel, I will get them.’

The elder man hesitated as if about to argue, but he went about his task, nervously poking about with his flashlight, while Stinnes watched him with ill-concealed contempt. He came upstairs too but he was an amateur. I stepped outside to avoid him. I need not have bothered even to do that, for he did little more than shine a light through the doorway to see if the bed was occupied. After no more than ten minutes he was back in the lounge telling Stinnes that the house was empty. ‘Now can we go back?’

‘You’ve gone soft, Pavel. Is that why Moscow sent you to be my assistant?’

‘You know why Moscow sent me here,’ the elder man grumbled.

Stinnes laughed briefly and I heard him put his glass down on the table. ‘Yes, I read your personal file. For “political realignment”. Whatever did you do in Moscow that the department thinks you are not politically reliable?’

‘Nothing. You know very well that that bastard got rid of me because I discovered he was taking bribes. One day his turn will come. A criminal like that cannot survive for ever.’

‘But meanwhile, Pavel, you suit me fine. You are politically unreliable and so the one man I can be sure will not report my unconventional views.’

‘You are my superior officer, Major Stinnes,’ said the older man stuffily.