По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

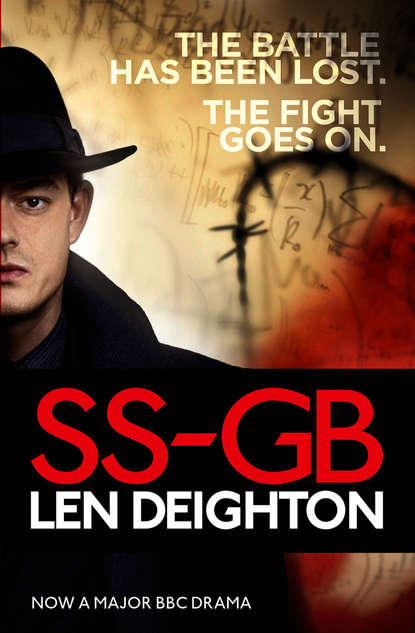

SS-GB

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter Twenty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Len Deighton (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#u34757546-68c2-5f77-aa05-3a0133075a98)

‘My book, Inside the Third Reich, never reached the top of the New York best seller list,’ Albert Speer told me. ‘It was Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex but were afraid to ask that always remained at number one.’

I am still not sure if he was joking. Hitler’s onetime Minister of Armaments had a sharp sense of humour, especially about the men with whom he had been in Spandau prison; he always referred to Field Marshal Milch as ‘Milk’. And when writers get together sales talk is not unusual.

But Albert Speer was not the catalyst for SS-GB. It began over a late-night drink with Ray Hawkey the writer and designer, and Tony Colwell my editor at Jonathan Cape. ‘No one knows what might have happened had we lost the Battle of Britain,’ said Tony with a sigh as we finished sorting through photos to illustrate my book, Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain.

‘I wouldn’t go as far as that,’ I told him. ‘A great deal of the planning for the German occupation has been found and published.’

I had read some of that material and, after this conversation, I sought out the official German publications and began wondering if Britain under German rule would make a book. It would have to be what was then called an ‘alternative world’ book and that was outside all my writing experience. On the other hand, research for Fighter and Funeral in Berlin and particularly Bomber, had brought me into contact with many Germans, mostly men who had fought in the war.

I work very slowly so I don’t embark on a story until I am confident that I will be able to get the material for it and live with it for many months, perhaps years. The plot problems seemed insurmountable. Would I create a hero in the German occupation army? I wouldn’t want a Nazi as a hero. If I told the story through the eyes of a British civilian how would such a person have enough information to make the plot work? A notable member of the resistance would qualify as a hero but such heroes would all be dead, or fugitives.

This story had to be told from the centre of power. The police would be the people who connected the conquerors with the conquered but that sort of compromise role was not attractive to me. I went round and round on this until I thought of a Scotland Yard detective as hero. A man who solved crimes and hunted only real criminals could have contacts at the top and yet still be acceptable as a central character. I would frame it like a conventional murder mystery, with corpse at the start and solution at the end.

I like big charts and diagrams. They serve as a guide and reminder while a book is being written. Using the German data I drew a chain of command showing the connections between the civilians and the puppet government, black-marketeers and quislings and the occupying power with its security forces and bitterly competitive army and Waffen SS elements. My old friend, and fellow writer, Ted Allbeury had spent the immediate post-war period in occupied Germany as what the locals called ‘the head of the British Gestapo’. Ted’s experience was very valuable indeed and I used his experience and anecdotes to the full.

For the London scenes, I used only places that I had known in the war, so in that respect there is an autobiographical element in the story. I remembered London in wartime: the dimly lit streets, gas lights that hissed and spluttered, tin baths in front of the fire, rationing that made food a constant subject of thought and conversation, and bombed homes that spewed their intimate household contents into the streets.

The Scotland Yard building had to be the stage upon which my story was played but the police were no longer using it. It had become an office building for members of parliament and was strictly guarded. The Metropolitan Police were very cooperative about letting me into their new building and they let me use their fascinating library and their archives too without restrictions of any kind. I spent many days studying wartime crimes and looking at pictures of Scotland Yard detectives in the natty suits that were mandatory at that time. But the obstacle remained, the police had no authority over the building they had vacated.

By a wonderful piece of luck I found an elderly ex-policeman who knew the building from cellar to attic. I recorded hours of his descriptions but I still could not get into it until a friend named Freddy Warren devised a method by which I could explore every nook and cranny of the historic Scotland Yard building. Freddy’s authority as an official of the Whip’s office was to allot the offices to the politicians. He took me on a guided tour. With him I went everywhere; opening doors, interrupting conferences, awakening sleepers and declining liquid refreshment. No one was going to risk upsetting Freddy. I remain indebted to him and I hope that this record of the Scotland Yard building, as once it was, justifies the trouble he took on my behalf.

When writing the main text begins I have found it beneficial to step away from phones and friends and any social commitments. Together with my wife Ysabele and two small children I climbed into an old Volvo with its trunk crammed with research material. We went to Tuscany. My friend Al Alvarez the writer and broadcaster lent us his wonderful mountainside house near Barga. It was winter and, no matter about the pictures in the brochures, winter in northern Italy is cold and wet. I searched far and wide for an electric typewriter and failed to find one. All I could find was a tiny lightweight portable Olivetti Lettera 22. Yes I know the Lettera 22 is an icon of the nineteen fifties and is found in design museums, but after the soft touch joys of an electric machine, pounding the mechanical keyboard took a lot of getting used to. My fingers swelled up like salsiccia Toscana. But rural Italy worked its magic. Our elderly ‘next door’ neighbours adopted us. Signora Ida and her husband Silvio lavished our children with love, made pizzas for us in their outdoor oven and showed us the secret of making ravioli and the secret of happiness on the slim budget that a few olive trees provide. We will never forget those two wonderful people. They made my time in Tuscany writing SS-GB one of the happiest times of my happy life.

Len Deighton, 2009

‘In England they’re filled with curiosity and keep asking, “Why doesn’t he come?” Be calm. Be calm. He’s coming! He’s coming!’

Adolf Hitler. 4 September 1940, at a rally of nurses and social workers in Berlin.

Oberste Befehlshaber

Berlin, den 18.2.41

Der Oberste Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht

10 Ausfertigungen Ausfertigung

Instrument of Surrender – English Text. Of all British armed forces in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland including all islands.

1 The British Command agrees to the surrender of all British armed forces in the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland including all islands and including military elements overseas. This also applies to units of the Royal Navy in all parts of the world, at port and on the high seas.

2 All hostilities on land, sea and in the air by British forces are to cease at 0800 hrs Greenwich Mean Time on 19 February 1941.

3 The British Command to carry out at once, without argument or comment, all further orders that will be issued by the German Command on any subject.

4 Disobedience of orders, or failure to comply with them, will be regarded as a breach of these surrender terms and will be dealt with by the German Command in accordance with the laws and usages of war.

5 This instrument of surrender is independent of, without prejudice to, and will be superseded by any general instrument of surrender imposed by or on behalf of the German Command and applicable to the United Kingdom and the Allied nations of the Commonwealth.

6 This instrument of surrender is written in German and English. The German version is the authentic text.

7 The decision of the German Command will be final if any doubt or dispute arises as to the meaning or interpretation of the surrender terms.

Chapter One (#u34757546-68c2-5f77-aa05-3a0133075a98)

‘Himmler’s got the king locked up in the Tower of London,’ said Harry Woods. ‘But now the German Generals say the army should guard him.’

The other man busied himself with the papers on his desk and made no comment. He thumped the rubber stamp into the pad and then on to the docket, ‘Scotland Yard. 14 Nov. 1941’. It was incredible that the war had started only two years ago. Now it was over; the fighting finished, the cause lost. There was so much paperwork that two shoe boxes were being used for the overflow; Dolcis shoes, size six, patent leather pumps, high heels, narrow fitting. Detective Superintendent Douglas Archer knew only one woman who would buy such shoes: his secretary.