По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

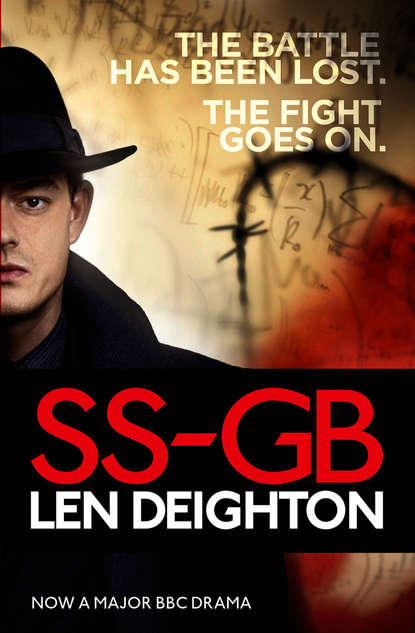

SS-GB

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Alopecia areata,’ said the doctor. ‘It’s common enough.’

Douglas looked into the mouth. The dead man had had enough money to pay for good dental care. Gold shone in his mouth but there was blood there too.

‘There’s blood in his mouth.’

‘Probably hit his face as he fell.’

Douglas didn’t think so but he didn’t argue. He noted the tiny ulcers on the man’s face and blood spots under the skin. He pushed back the shirt sleeve far enough to see the red inflamed arm.

‘Where do you find such sunshine at this time of the year?’ the doctor said.

Douglas didn’t answer. He drew a small sketch of the way that the body had fallen backwards into the tiny bedroom, and guessed that he’d been in the doorway when the bullets hit him. He touched the blood on the body to see if it was tacky, and then placed a palm on the chest. He could feel no warmth at all. His experience told him that this man had been dead for six hours or more. The doctor watched Douglas but made no comment. Douglas got to his feet and looked round the room. It was a tiny place, over-decorated with fancy wallpapers, Picasso reproductions and table lights made from Chianti bottles.

There was a walnut escritoire, with its front open as if it might have been rifled. An old-fashioned brass lamp had been adjusted to bring the light close upon the green leather writing top but its bulb had been taken out and left in one of the pigeon-holes, together with some cheap writing paper and envelopes.

There were no books, no photos and nothing personal of any kind. It was like some very superior sort of hotel room. In the tiny open fireplace there was a basket of logs. The grate was overflowing with ashes of paper.

‘Pathologist here yet?’ Douglas asked. He fitted the light bulb into the brass lamp. Then he switched it on for long enough to see that the bulb was still in working order and switched it off again. He went to the fireplace and put his hand into the ash. It was not warm but there was no surviving scrap of paper to reveal what had been burned there. It was a long job to burn so much paper. Douglas used his handkerchief to wipe his hands.

‘Not yet,’ said the doctor in a dull voice. Douglas guessed that he resented being ordered to wait.

‘What do you make of it, doc?’

‘You get any spare cigarettes, working with the SIPO?’

Douglas produced the gold cigarette case that was his one and only precious possession. The doctor took the cigarette and nodded his thanks while examining it carefully. Its paper was marked with the double red bands that identified Wehrmacht rations. The doctor put it in his mouth, brought a lighter from his pocket and lit it, all without changing his expression or his position, sprawled on the couch with legs extended.

A uniformed Police Sergeant had watched all this while waiting on the tiny landing outside the door. Now he put his head into the room and said, ‘Pardon me, sir. A message from the pathologist. He won’t be here until this afternoon.’

Harry Woods was unpacking the murder bag. Douglas could not resist glancing at him. Harry nodded. Now he realized that to keep the Police Surgeon here was a good idea. The pathologists were always late these days. ‘So what do you make of it, doctor?’ said Douglas.

They both looked down at the body. Douglas touched the dead man’s shoes; the feet were always the last to stiffen.

‘The photographers have finished until the pathologist comes,’ said Harry. Douglas unbuttoned the dead man’s shirt to reveal huge black bruises surrounding two holes upon which there was a crust of dried blood.

‘What do I make of it?’ said the doctor. ‘Gunshot wound in chest caused death. First bullet into the heart, second one into the top of the lung. Death more or less instantaneous. Can I go now?’

‘I won’t keep you longer than absolutely necessary,’ said Douglas without any note of apology in his voice. From his position crouched down with the body, he looked back to where the killer must have been. At the wall, far under the chair he saw a glint of metal. Douglas went over and reached for it. It was a small construction of alloy, with a leather rim. He put it into his waistcoat pocket. ‘So it was the first bullet that entered the heart, doctor, not the second one?’

The doctor still had not moved from his fixed posture on the couch but now he twisted his feet until his toes touched together. ‘There would have been more frothy blood if a bullet had hit the lung first while the heart was pumping.’

‘Really,’ said Douglas.

‘He might have been falling by the time the second shot came. That would account for it going wide.’

‘I see.’

‘I saw enough gunshot wounds last year to become a minor expert,’ said the doctor without smiling. ‘Nine millimetre pistol. That’s the sort of bullets you’ll find when you dig into the plaster behind that bloody awful Regency stripe wallpaper. Someone who knew him did it. I’d look for a lefthanded ex-soldier who came here often and had his own key to get in.’

‘Good work, doctor.’ Harry Woods looked up from where he was going through the dead man’s pockets. He recognized the note of sarcasm.

‘You know my methods, Watson,’ said the doctor.

‘Dead man wearing an overcoat; you conclude he came in the door to find the killer waiting. You guess the two men faced each other squarely with the killer in the chair by the fireplace, and from the path of the wound you guess the gun was in the killer’s left hand.’

‘Damned good cigarettes these Germans give you,’ said the doctor, holding it in the air and looking at the smoke.

‘And an ex-soldier because he pierced the heart with the first shot.’ The doctor inhaled and nodded. ‘Have you noticed that all three of us are still wearing overcoats?’ said Douglas. ‘It’s bloody cold in here and the gas meter is empty and the supply disconnected. And not many soldiers are expert shots, doc, and not one in a million is an expert with a pistol, and by your evidence a German pistol at that. And you think the killer had a key because you can’t see any signs of the door being forced. But my Sergeant could get through that door using a strip of celluloid faster than you could open it with a key, and more quietly too.’

‘Oh,’ said the doctor.

‘Now, what about a time of death?’ said Douglas.

All doctors hate to estimate the time of death and this doctor made sure the policemen knew that. He shrugged. ‘I can think of a number and double it.’

‘Think of a number, doc,’ said Douglas, ‘but don’t double it.’

The doctor, still lolling on the couch, pinched out his cigarette and put the stub away in a dented tobacco tin. ‘I took the temperature when I arrived. The normal calculation is that a body cools one-and-a-half degrees Fahrenheit per hour.’

‘I’d heard a rumour to that effect,’ said Douglas.

The doctor gave him a mirthless grin as he put the tin in his overcoat pocket, and watched his feet as he made the toes touch together again. ‘Could have been between six and seven this morning.’

Douglas looked at the uniformed Sergeant. ‘Who reported it?’

‘The downstairs neighbour brings a bottle of milk up here each morning. He found the door open. No smell of cordite or anything,’ added the Sergeant.

The doctor chortled. When it turned into a cough he thumped his chest. ‘No smell of cordite,’ he repeated. ‘I’ll remember that one, that’s rather rich.’

‘You don’t know much about coppers, doc,’ said Douglas. ‘Specially when you take into account that you are a Police Surgeon. The uniformed Sergeant here, an officer I’ve never met before, is politely hinting to me that he thinks the time of death was earlier. Much earlier, doc.’ Douglas went over to the elaborately painted corner cupboard and opened it to reveal an impressive display of drink. He picked up a bottle of whisky and noted without surprise that most of the labels said ‘Specially bottled for the Wehrmacht’. Douglas replaced the bottles and closed the cupboard. ‘Have you ever heard of postmortem lividity, doctor?’ he said.

‘Death might have been earlier,’ admitted the doctor. He was sitting upright now and his voice was soft. He, too, had noticed the coloration that comes from settling of the blood.

‘But not before midnight.’

‘No, not before midnight,’ agreed the doctor.

‘In other words death took place during curfew?’

‘Very likely.’

‘Very likely?’ said Douglas caustically.

‘Definitely during curfew,’ admitted the doctor.

‘What kind of a game are you playing, doc?’ said Douglas. He didn’t look at the doctor. He went to the fireplace and examined the huge pile of charred paper that was stuffed into the tiny grate. The highly polished brass poker was browned with smoke marks. Someone had used it to make sure that every last piece of paper was consumed by the flames. Again Douglas put his hand into the feathery layers of ash; there must have been a huge pile of foolscap and it was quite cold. ‘Contents of his pockets, Harry?’

‘Identity card, eight pounds, three shillings and tenpence, a bunch of keys, penknife, expensive fountain pen; handkerchief, no laundry marks, and a railway ticket monthly return half; London to Bringle Sands.’