По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

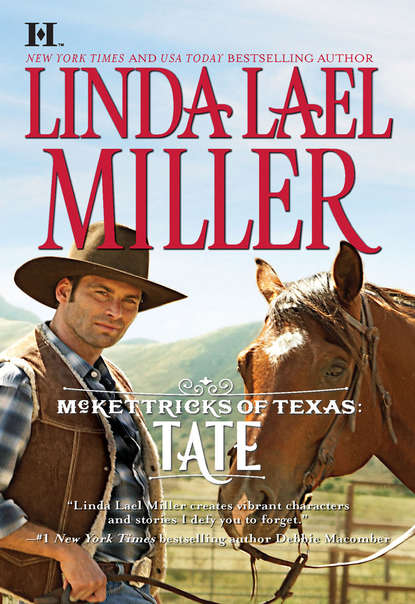

McKettricks of Texas: Tate

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Libby frowned. In the old days, she and Julie and Paige had played a lot of backyard croquet with their dad, and she cherished the recollection. She’d been proud that when other daddies were on the golf course with their friends and business associates, hers had chosen to spend the time with her and her sisters. “What’s wrong with that?”

He sighed, stood with his arms folded, his head tilted back. He’d always loved looking at the stars, said that was why he’d never be happy in a big city. “Nothing,” he admitted. “But I kind of lost my head after the castle and the ponies were delivered. Call it male ego.”

“You’re not going to change your mind about the dogs, are you?” Libby asked, worried all over again.

Tate gripped the edge of her open window and bent to look in at her. His face was mere inches from hers, and for one terrible, wonderful, wildly confusing moment, she thought he was going to kiss her.

He didn’t, though.

“I’m not going to change my mind, Lib,” he said. “The mutts will have a home as long as I do.”

“You wouldn’t send them to town to live with your wife?”

“Ex-wife,” Tate said. “No, Cheryl’s not a dog person. Like the ponies, they’ll live right here on the Silver Spur for the duration.”

“Okay,” Libby said, now almost desperate to be gone.

And oddly, equally desperate to stay.

Tate straightened, smiled down at her. Half turned again, toward the house. Toward his daughters and the dogs that were already loved and would soon be named, toward his brother Garrett and Esperanza, the housekeeper.

But then he turned back.

“I don’t suppose you’d like to have dinner with me some night?” he asked, sounding as shy as he had that long-ago day when he’d asked her to the junior prom. “Soon?”

CHAPTER THREE

“I CAN’T PAY YOU,” Libby warned, the next morning, when her sister Julie showed up at the shop, all set to bake scones and chocolate-chip cookies, her four-year-old son Calvin in tow. Clad in swim trunks and flip-flops, with a plastic ring around his waist, Libby’s favorite—and only—nephew had clearly made up his mind to take advantage of the first body of water to present itself.

He adjusted his horn-rimmed glasses, with the chunk of none-too-clean tape holding the bridge together, and climbed onto one of three stools lining the short counter.

Libby ruffled his hair. “Hey, buddy,” she said. “Want an orange smoothie?”

“No, thanks,” Calvin replied glumly.

Julie, twenty-nine, with long, naturally auburn hair that fell to the middle of her back in spiral curls—also natural—and a figure that would do any exercise maven proud, wore jeans and a royal blue long-sleeved T-shirt. Thus her hazel eyes, which tended to reflect whatever color she was wearing that day, were the pure azure of a clear spring sky. She grinned at Libby and headed for the tiny kitchen in the back of the shop.

“You could take my week troubleshooting with Marva,” she sang. “Instead of paying me wages, I mean.”

“Not a chance,” Libby said, but the refusal was rhetorical, and Julie knew that as well as she did. The three sisters rotated, week by week, taking responsibility for their mother, which meant visiting regularly, settling the problems Marva invariably caused with neighbors and hunting her down when she decided to take off on one of her hikes into the countryside and got lost. Marva was always up to something.

“Mom doesn’t have anything better to do anyway,” Calvin confided solemnly. He was precocious for his age, and he’d already been reading for a year. Julie, a high school English and drama teacher, was off for the summer, and her usual fill-in job at the insurance agency had fallen through for some unspecified reason. “You might as well let her make scones.”

Libby chuckled and couldn’t resist planting a smacking kiss on Calvin’s cheek. “The community pool is closed for maintenance this week,” she reminded him. “So what’s with the trunks and the plastic inner tube?”

Calvin’s eyes were a pale, crystalline blue, like those of his long-gone father, a man Julie had met while she was student teaching in Galveston, after college. As close as she and Julie were, Libby knew very little about Gordon Pruett, except that he’d owned a fishing boat and was a lot better at going away than coming back. He’d stayed around long enough to pass his unique eye color on to his son and name him Calvin, for his favorite uncle, but soon enough he’d felt compelled to move on.

Gordon didn’t visit, but he wasn’t completely worthless. He remembered birthdays, mailed his son a box of awkwardly wrapped presents every Christmas, and sent Julie a few hundred dollars in child support each month.

Most of the time, the checks even cleared the bank.

Calvin pushed his everyday glasses up his nose—he had better ones for important occasions. “I know the pool is closed for maintenance, Aunt Libby,” he said, “but the kid next door to us—Justin?—well, his mom and dad bought him a swimming pool, the kind you blow up with a bicycle pump. His dad filled it with a garden hose this morning, but Justin’s mom said we can’t swim until the sun heats the water up. I just want to be ready.”

Julie chuckled as she came out of the kitchen. She’d already managed to get flour all over the front of her fresh apron. “Hey, Mark Spitz,” she said to her son, “how about going next door for a five-pound bag of sugar? Give you a nickel for your trouble.”

Almsted’s, probably one of the last surviving mom-and-pop grocery stores in that part of Texas, was something of a local institution, as much a museum as a place of business.

“You can’t buy anything for a nickel,” Calvin scoffed, but he climbed down from the stool and held out one palm, reporting for duty.

Libby gave him a few dollars from the till to pay for the sugar, and Calvin marched himself out onto the sidewalk, headed next door.

Julie immediately stationed herself at a side window, in order to keep an eye on him. No child had ever gone missing from Blue River, but a person couldn’t be too careful.

“We’ve already got plenty of sugar,” Libby said.

“I know,” Julie answered, watching as her son went into Almsted’s, with its peeling, green-painted wooden screen door. “I have something to tell you, and I don’t want Calvin to hear.”

Libby, busy getting ready for the Monday-morning latte rush, went still. “Is something wrong?”

“Gordon e-mailed me,” Julie said, still keeping her careful vigil. “He’s married and he and his wife pass through town often, on the way to visit his parents in Tulsa, and now Gordon and the little woman want to stop by sometime soon, and get acquainted with Calvin.”

“That sounds harmless,” Libby observed, though she felt a prickle of uneasiness at the news.

“I don’t like it,” Julie replied firmly. She smiled, which meant Calvin had reappeared, lugging the bag of sugar, and stepped back so he wouldn’t see her. “What if Gordon decides to be an actual, step-up father, now that he’s married?”

“Julie, he is Calvin’s father—”

Julie made a throat-slashing motion with one hand, and Calvin struggled through the front door, might have been squashed by it if he hadn’t been wearing the miniature inner tube with the goggle-eyed frog-head on the front.

“Here,” he said, holding the bag out to his mother. “Where’s my nickel?”

Julie paid up, casting a warning glance in Libby’s direction as she did so. There was to be no more talk of Gordon Pruett’s impending visit while Calvin was around.

“I’m bored,” Calvin soon announced. “I want to go to playschool over at the community center.”

“You should have thought of that when you insisted on wearing swimming trunks and the floaty thing with the frog-head,” Julie responded lightly, heading back toward the kitchen with the unnecessary bag of sugar. “You’re not dressed for playschool, kiddo.”

“There’s a dress code?” Libby asked. She generally took Calvin’s side when there was a difference of opinion.

“No,” Julie conceded brightly, “but I’d be willing to bet nobody else is wearing a bathing suit.”

Two secretaries came in then, for their double nonfat lattes, following by Jubal Tabor, a lineman for the power company. In his midforties, with a receding hairline and a needy personality, Jubal always ordered the Rocket, a high-caffeine concoction with ginseng and a lot of sugar. Said it got him through the morning.

“Expectin’ a flood, kid?” he asked Calvin, who was back on his stool, shoulders hunched, frog-head slightly askew.

Calvin rolled his eyes.

Hiding a smile, Libby served the secretaries’ drinks, took their money and thanked them.