По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

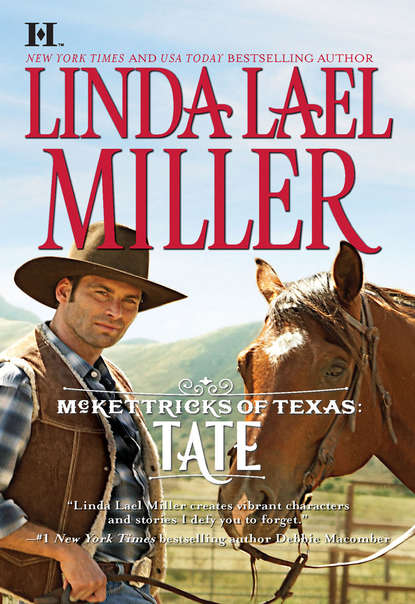

McKettricks of Texas: Tate

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Meanwhile, Julie made sure she stayed in the kitchen. Jubal asked her to the movies nearly every time their paths crossed, and even now he was standing on tiptoe trying to catch a glimpse of her while the espresso for his Rocket steamed out of the steel spigot.

“He’s not so bad,” Libby had said once, when Julie had sent Jubal away with another carefully worded rejection.

“Julie and Jubal?” her sister had said, her eyes green that day because she was wearing a mint-colored blouse. “Our names alone are reason enough to steer clear—we’d sound like second cousins to the Bobbsey twins. Besides, he’s too old for me, he wears white socks and he always calls Calvin ‘kid.’”

The admittedly comical ring of their names, Jubal’s age and the white socks might have been overlooked, in Libby’s opinion, but the gruff way he said “kid” whenever he spoke to Calvin bugged her, too. So she’d stopped reminding her sister that there was a shortage of marriageable men in Blue River.

“Scones aren’t ready yet?” Jubal asked, casting a disapproving eye toward the virtually empty plastic bakery display case beside the cash register. “Out at Starbucks, they’ve always got scones.”

Libby refrained from pointing out to Jubal that he never bought scones anyway, no matter how good the selection was, and set his drink on the counter. “You been cheating on me, Jubal?” she teased. “Buying your jet fuel from the competition?”

Jubal looked at her and blinked once, hard, as though he’d never seen her before. “You want to go to the movies with me tonight?” he asked.

Calvin made a rude sound, which Jubal either missed or pretended not to hear.

“I’m sorry,” Libby said, with a note of kind regret in her voice. “I promised Tate McKettrick I’d have dinner with him.”

Julie dropped something in the kitchen, causing a great clatter, and out of the corner of her eye, Libby saw Calvin watching her with renewed interest. Since he’d been born long after the breakup, he couldn’t have registered the implications of his aunt’s statement, but that well-known surname had a cachet all its own.

Even among four-year-olds, it seemed.

“Well,” Jubal groused, “far be it from me to compete with a McKettrick.”

Libby merely smiled. “Thanks for the business, Jubal,” she told him. “You have yourself a good day, now.”

Jubal paid up, took his Rocket and left.

The instant his utility van pulled away from the curb, Julie peeked out of the kitchen. “Did I hear you say you’re going to dinner with Tate?” she asked.

Libby tried to act casual. “He asked me last night. I said maybe.”

“That isn’t what you told Mr. Tabor,” Calvin piped up. “You lied.”

“I didn’t lie,” Libby lied. First, she’d driven her car without the emissions repair, single-handedly destroying the environment, to hear her conscience tell it, and now this. She was setting a really bad example for her nephew.

“Yes, you did,” Calvin insisted.

“Sometimes,” Julie said carefully, resting a hand on Calvin’s small, bare shoulder, “we say things that aren’t precisely true so we don’t hurt other people’s feelings.”

Calvin held his ground. “If it’s not the truth, then it’s a lie. That’s what you always tell me, Mom.”

Libby sighed. “If Tate asks me out again,” she told Calvin, “I’ll say yes. That way, I won’t have fibbed to anybody.”

“I can’t believe you didn’t say ‘yes’ in the first place,” Julie marveled. “Elisabeth Remington, are you crazy?”

Libby cleared her throat, slanted a glance in Calvin’s direction to remind her sister that the conversation would have to wait.

“Can I go to playschool if I put on clothes?” Calvin asked, looking so woeful that Julie mussed his hair and ducked out of her floury apron.

“Sure,” she said. “Let’s run home so you can change.” She turned to Libby. “I put the first batch of scones in the oven a couple of minutes ago,” she added. “When you hear the timer ding, take them out.”

“Are you coming back?” Libby asked, as equally invested in a “no” as she was in a “yes.” Once she and her sister were alone again, between customers, Julie would grill her about Tate. If Julie didn’t return, the first batch of scones would sell out in a heartbeat, as always, and there wouldn’t be any more for the rest of the day, because Libby always burned everything she baked, no matter how careful she was.

“Only if you promise to take my turn babysitting Marva so I can—” Julie paused, cleared her throat “—leave town for a few days.”

“We’re going somewhere?” Calvin asked, immediately excited. On a teacher’s salary, with the child support going into a college account, he and Julie didn’t take vacations.

“Yes,” Julie answered, passing Libby an arch look. “If your aunt Libby will agree to look after Gramma while we’re gone, that is.”

Calvin sagged with disappointment. “Nobody,” he said, “wants to spend any more time with Gramma than they have to.”

“Calvin Remington,” Julie replied, without much sternness to her tone, “that was a terrible thing to say.”

“You say it all the time.”

“It’s still terrible, all right?” Julie turned to Libby. “Deal or no deal?”

Agreeing would mean two weeks in a row on Marva-watch. But Libby needed those scones, if she didn’t want all her customers heading for Starbucks. “Deal,” she said, in dismal resignation.

Julie grinned. “Great. See you in twenty minutes.”

“Crap,” Libby muttered, when her sister and nephew had reached the sidewalk and she knew Calvin wouldn’t hear.

Julie took half an hour to get back, not twenty minutes, and in the meantime there was a run on iced coffee, so Libby nearly missed the “ding” of the timer on the oven. She rescued the scones in the nick of time and sold the last one just as Julie waltzed in, all pleased with herself.

“You’re going, aren’t you?” she asked, as soon as the customer and the scone were gone. “If Tate asks you out to dinner again, you’ll say ‘yes,’ not ‘maybe’?”

“Maybe,” Libby said, annoyed. “And thanks a heap for sticking me with Marva for an extra week. I covered for you last month, remember, when you wanted to take your twelfth-grade drama class on that field trip to Dallas.”

“They learned so much about Shakespeare,” Julie said.

“And I came to understand the mysteries of matricide,” Libby said, cleaning the spigots on the espresso machine with a paper towel. “Are you seriously planning to leave town so you can avoid Gordon and the new bride?”

“Yes,” Julie answered. “According to his e-mail, he sold his boat, or it sank or both and it went for salvage—I forget. That means good old Gordon is thinking of settling down, and I don’t want him asking for joint custody or something, just because he’s got a wife now.”

“I understand where you’re coming from, Julie,” Libby said, after taking a few moments to prepare, “but you won’t be able to hide from Gordon forever—if he really wants to be part of Calvin’s life, he’ll find a way. And he has a right to at least see the little guy once in a while.”

“Gordon Pruett is the most irresponsible man on the planet,” Julie reminded Libby, her eyes suspiciously bright and her voice shaking a little. “I can’t turn Calvin over to him every other weekend, or for whole summers or for holidays. For one thing, there’s the asthma.”

A silence fell between them.

Libby hadn’t witnessed one of Calvin’s asthma attacks recently, but when they happened, they were terrifying. Once, when he was still in diapers, he’d all but stopped breathing. Libby’s youngest sister, Paige, an RN, had jumped up and made sure he wasn’t choking, then grabbed him from his high chair at the Thanksgiving dinner table at a neighbor’s house, yelled for someone to call 911 and rushed to the shower, where she’d thrust the by-then-blue baby under an icy spray, drenching herself in the process, holding him there until his lungs were shocked into action.

Libby could still hear his affronted, frightened shrieks, see him soaked and struggling to get to Julie, who bundled him in a towel and held him close, once he’d gotten his breath again, whispering to him, singing softly, desperate to calm him down.

Paige had calmly turned on the hot water spigot in the shower then, and filled the bathroom with steam, and Julie had sat on the lid of the toilet, rocking a whimpering Calvin in her arms until the paramedics arrived.

The toddler had spent nearly a week in the pediatric ward of a San Antonio hospital, Julie at his bedside around the clock, and it had taken Paige months to win back his trust. He was simply too little to understand that she’d saved his life.