По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

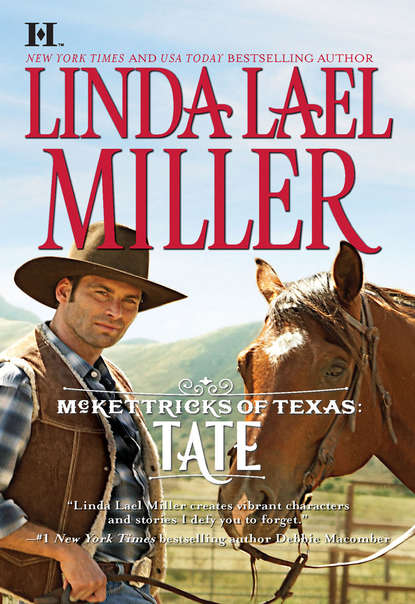

McKettricks of Texas: Tate

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“You and Hildie and I are having supper on the Silver Spur, just like we planned. I’ll just call Esperanza and ask her to feed the girls early.”

“But—”

Tate took in Libby’s sundress, her strappy sandals, her semi-big hair. “You look better than fantastic,” he said. Then he took Libby by the arm and squired her toward the front door, Hildie happily trotting alongside.

His truck was parked at the curb, and he hoisted Hildie into the back seat, then opened the passenger-side door for Libby. Helped her onto the running board, from which point she was able to come in for a landing on the leather seat with something at least resembling dignity.

“You don’t have to do this,” she said.

Tate didn’t answer until he’d rounded the front of the truck and climbed behind the wheel. “I don’t have to do anything but die and pay taxes,” he replied, with a grin. “I’m here because I want to be here, Lib. No other reason.”

Within five minutes, they were pulling into one of the parking lots at Poplar Bend, behind Building B. Marva lived off the central courtyard, and as they approached, she stepped out onto her small patio, smiling cheerfully. A glass of white wine in one hand, she wore white linen slacks and a matching shirt, tasteful sandals and earrings.

Libby stared at her.

“Well, this is a nice surprise,” Marva said, her eyes gliding over Tate McKettrick briefly before shifting back to her daughter. “To what do I owe the pleasure?”

“Gerbera Jackson called me,” Libby said, struggling to keep her tone even. “She was very concerned because you didn’t want to watch your soap operas or eat supper.”

Marva sighed charitably and shook her head. “I was just having a little blue spell, that’s all,” she said. She raised the wineglass, its contents shimmering in the late-afternoon light. “Care for a drink?”

Inwardly, Libby seethed. Gerbera was a sensible woman, and if she’d been concerned about Marva’s behavior, then Marva had given her good reason for it.

Bottom line, Marva had decided she wanted a little attention. Instead of just saying so, she’d manipulated Gerbera into raising an unnecessary alarm.

“No, thanks,” Tate said, nodding affably at Marva. “Is there anything you need, ma’am?”

Libby wanted to jab him with her elbow, but she couldn’t, because Marva would see.

“Well,” Marva said, almost purring, “there is that light in the kitchen. It’s been burned out for weeks and I’m afraid I’ll break my neck if I get up on a ladder and try to replace the bulb.”

Tate rolled up his sleeves. “Glad to help,” he said.

Libby’s smile felt fixed; she could only hope it looked more genuine than it felt, quivering on her mouth.

Tate replaced the bulb in Marva’s kitchen.

“It’s good to have a man around the house,” Marva said.

Libby all but rolled her eyes. You had one, she thought. You had Dad. And he wasn’t exciting enough for you.

“I guess Libby and I ought to get going,” Tate told Marva. “Esperanza will be holding supper for us.”

Marva patted his arm, giving Libby a sly wink, probably in reference to Tate’s well-developed biceps. “You young people run along and have a nice evening,” she said, setting aside her now-empty wineglass to wave them out of the condo. “It’s nice to know you’re dating, Libby,” she added, her tone sunny. “You and your sisters need to have more fun.”

Libby’s cheeks burned.

Tate took her by the elbow, nodded a good evening to Marva, and they were out of the condo, headed down the walk.

When they reached the truck, Tate lifted Libby bodily into the cab, paused to reach back and pet Hildie reassuringly before sprinting around to the driver’s-side door, climbing in and taking the wheel again.

As soon as he turned the key in the ignition, the air-conditioning kicked in, cooling Libby’s flesh, if not her temper.

She leaned back in the seat, then closed her eyes. Stopping by Marva’s place had been no big deal, as it turned out, and Tate certainly hadn’t minded changing the lightbulb.

But of course, those things weren’t at the heart of the problem, anyway, were they?

All this emotional churning was about Marva’s leaving, so many years ago.

It was about her and Julie and Paige, not to mention their dad, missing her so much.

Marva had departed with a lot of fanfare. Now that she was back, she expected to be treated like any normal mother.

Not.

“I guess your mom still gets under your hide,” Tate commented quietly, once they were moving again.

Libby turned her head, looked at him. “Yes,” she admitted. He knew the story—everyone around Blue River did. Several times, when they were younger, he’d held her while she cried over Marva.

Tate was thoughtful, and silent for a long time. “She’s probably doing the best she can,” he said, when they were past the town limits and rolling down the open road. “Like the rest of us.”

Libby nodded. Marva’s “best” wasn’t all that good, as it happened, but she didn’t want the subject of her mother to ruin the evening. She raised and lowered her shoulders, releasing tension, and focused on the scenery. “I guess so,” she said.

The conversational lull that followed was peaceful, easy.

Hildie got things going again by suddenly popping her big head forward from the back seat and giving Tate an impromptu lick on the ear.

He laughed, and so did Libby.

“Do you ever think about getting another dog?” she asked, thinking of Crockett. That old hound had been Tate’s constant companion. He’d even taken him to college with him.

“Got two,” Tate reminded Libby, grinning.

“I mean, one of your own,” Libby said.

Tate swallowed, shook his head. “I keep thinking I’ll be ready,” he replied, keeping his gaze fixed on the winding road ahead. “But it hasn’t happened yet. Crockett and I, we were pretty tight.”

Libby watched him, took in his strong profile and the proud way he held his head up high. It was a McKettrick thing, that quiet dignity.

“Your folks were such nice people,” she told Tate.

He smiled. “Yeah,” he agreed. “They were.”

They’d passed mile after mile of grassy rangeland by then, dotted with cattle and horses, all of it part of the Silver Spur. Once, there had been oil wells, too, pumping night and day for fifty years or better, though Tate’s father had shut them down years before.

A few rusty relics remained, hulking and rounded at the top; in the fading, purplish light of early evening, they reminded Libby of the dinosaurs that must have shaken the ground with their footsteps and dwarfed the primordial trees with their bulk.

“You’re pretty far away,” Tate said, as they turned in at the towering wrought-iron gates with the name McKettrick scrolled across them. Those gates had been standing open the night before; Libby, relieved not to have to stop, push the button on the intercom and identify herself to someone inside, had breezed right in. “What are you thinking about, Lib?”