По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

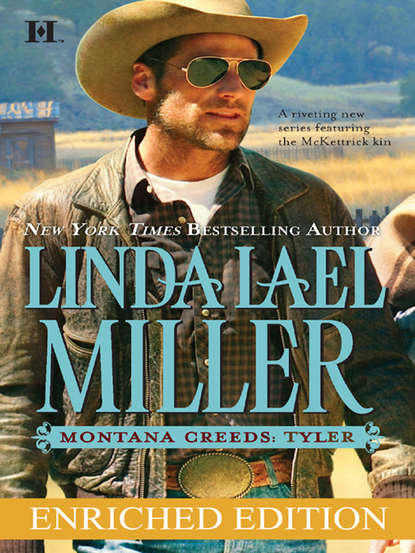

Montana Creeds: Tyler

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

L ILY K ENYON WASN’T HAVING second thoughts about staying on in Montana to look after her ailing father as she and a nurse muscled him into her rented Taurus in front of Missoula General Hospital. She was having forty-third thoughts, seventy-eighth thoughts; she’d left second ones behind about half an hour after she and her six-year-old daughter, Tess, rushed into the admittance office a week before, fresh from the airport.

Lily had remembered her father as a good-natured if somewhat distracted man, even-tempered and funny. Until her teens, she’d spent summers in Stillwater Springs, sticking to his heels like a wad of chewing gum as he saw four-legged patients in his veterinary clinic, trailing him from barn to barn while he made his rounds, tending sick cows, horses, goats and barn cats. He’d been kind, referring to her as his assistant and calling her “Doc Ryder,” and it had made her feel proud, because that was what folks in that small Montana community called him .

In those little-girl days, Lily had wanted to be just like her dad.

Now, though, she was having a hard time squaring the man she recalled with the one her bitter, angry mother described after the divorce. The one who never showed up on the doorstep, sent Christmas or birthday cards, or even called to ask how she was.

Let alone sent a plane ticket so she could visit.

Now, after seven long days of putting up with his crotchety ways, she understood her mom’s attitude a little better, even though it still smarted, the way Lucy Ryder Cook could never speak of her ex-husband without pursing her lips afterward. Hal Ryder, aka Doc, seemed fond of Tess, but every time he looked at Lily, she saw angry, baffled pain in his eyes.

Once her father and daughter were buckled in, Hal in the front and Tess in the special booster seat the law required of anyone under a certain age and height, Lily slid behind the wheel and tried to center herself. The day was hot, even for July; the hospital had been blessedly cool, but the vents on the dashboard of the rental were still huffing out blasts of heat.

Sweat dampened the back of Lily’s sleeveless blouse; without even turning a wheel, she was already sticking to the seat.

Not good.

“Can we get hamburgers?” Tess piped from the backseat.

“No,” said Lily, who placed great stock in eating healthfully.

“Yes,” challenged her curmudgeon of a father, at exactly the same moment.

“Which?” Tess inquired patiently. “Yes or no?” The poor kid was nothing if not pragmatic—stoic, too. She’d had a lot of practice at resigning herself to things since Burke’s “accident” a year before. Lily hadn’t had the heart to tell her little girl what everyone else knew—that Burke Kenyon, Lily’s estranged husband and Tess’s father, had crashed his small private plane into a bridge on purpose, in a fit of spiteful melancholy.

“No,” Lily said firmly, after glaring eloquently at her dad for a moment. “You’re recovering from a heart attack,” she reminded him. “You are not supposed to eat fried food.”

“There’s such a thing as quality of life, you know,” Hal Ryder grumped. He looked thin, and there were bluish-gray shadows under his eyes, underlaid by pouches of skin. “And if you think I’m going to live on tofu and sprouts until my dying day, you’d better think again.”

Lily shifted the car into gear, and the tires screeched a little on the sun-softened pavement as she pulled away from the hospital entrance. “Listen,” she replied tersely, at her wit’s end from stress and lack of sleep, “if you want to clog your arteries with grease and poison your system with preservatives and God only knows what else, that’s your business. Tess and I intend to live long, healthy lives.”

“Long, boring lives,” Hal complained. Lily had stopped thinking of him as “Dad” years before, when it first dawned on her that he wouldn’t be flying her out to Montana for any more small-town, barefoot-and-Popsicle summers. He hadn’t approved of her teenage romance with Tyler Creed, and she’d always suspected that was part of the reason he’d cut her out of his life.

“I’d be happy to hire a nurse,” Lily said, shoving Tyler to the back of her mind and biting her lip as she navigated thickening late-morning traffic. “Tess and I can go back to Chicago if you’d prefer.”

“Don’t be mean, Mom,” Tess counseled sagely. “Grampa’s heart attacked him, remember.”

The image of a ticker gone berserk filled Lily’s mind. If the subject hadn’t been so serious, she’d have smiled.

“Yeah,” Hal agreed. “Don’t be mean. It reminds me of Lucy, and I like to think about her as little as possible.”

Since Lily wasn’t on much better terms with her mother than she was with Hal, she could have done without that last remark. She peeled her back from the seat and fumbled with the air-conditioning, keeping one eye on the road. Her cotton shorts had ridden up, so her thighs were stuck, too, and it would hurt to pull them free.

Another thing to dread.

“Gee, thanks,” she muttered.

“Nana’s a stinker,” Tess commented, her tone cheerful and affectionately tolerant.

“Hush,” Lily said, though she secretly agreed. “That wasn’t a nice thing to say.”

“Well, she is, ” Tess insisted.

“Amen,” Hal added.

“Enough,” Lily muttered. “Both of you. I’m trying to drive, here. Keep us all alive.”

“Slow down a little, then,” Hal grumbled. “This isn’t Chicago.”

“Don’t remind me.” Lily hadn’t intended to sound sarcastic, but she had.

“Is your house big, Grampa?” Tess asked, bravely trying to steer the conversation onto more amiable ground. “Can I have my mom’s old room?”

Lily flashed on the big, rambling Victorian that had once been her home, with its delightful nooks and crannies, its cluttered library stuffed with books, its window seats and alcoves and brick fireplaces. Remembering, she felt the loss afresh, and something squeezed at the back of her heart.

“You can,” Hal said, with a gentleness Lily almost envied. She felt his gaze touch her, sidelong and serious. “Is there a man waiting in Chicago, Lily—is that why you want to go back?”

Lily tensed, searching for the freeway on-ramp, wondering if the question had a subtext. After all, Lily’s mother had left her father for another man, and he hadn’t remarried during the intervening years. Maybe he mistrusted women—his only daughter included. Maybe he expected her to drop everything and run back home to some guy she’d met at Burke’s funeral.

She sighed and shoved a hand into her blond, chin-length hair, only to catch her fingers in the plastic clip she’d used to gather it haphazardly on top of her head that morning before leaving the motel for the hospital. She wasn’t being fair. Her dad had suffered a serious coronary incident, and the doctors and nurses at Missoula General had warned her that depression was common in patients who suddenly found themselves dependent on other people for their care.

Hal Ryder had been doing what he pleased, at least since the divorce. Now, he needed her, a near stranger, to fix his meals, sort out his prescriptions, which were complicated, and see that he didn’t try to mow his lawn or fling himself back into his thriving practice before he was ready.

“Lily?” he prompted.

“No,” she said, after thumbing back through her thoughts for the original question. “There’s no man, Hal.”

“Mom’s a black widow,” Tess explained earnestly.

Hal chuckled. “I wouldn’t go that far, cupcake,” he told his granddaughter.

For a reason Lily couldn’t have explained, her eyes filled with sudden, scalding tears—and she blinked them away. Tears were dangerous on a busy freeway, and besides that, they never made things better. “I’m a widow, ” Lily corrected her daughter calmly. “A black widow is a spider.”

“Oh,” Tess said, digesting the science lesson. She began to thump her sandaled heels against the front of her seat, something she did when she was impatient for the drive to be over.

“Stop,” Lily told her.

A few moments of silence passed. Then Tess went on. “My daddy died when I was four,” she announced.

“I know, sweetheart,” Hal said, his voice tender and a little gruff.

Lily’s throat ached. She’d filed for divorce, after a tearful call from Burke’s latest girlfriend, whom he’d apparently dropped. Would he still be alive if she’d waited, agreed to more marriage counseling, instead of calling a lawyer right after hanging up with the mistress? Would her child still have a father?

Tess had adored her dad.

“His plane hit a bridge,” Tess said.

“Tess,” Lily said gently, “could we talk about this later, please?”