По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

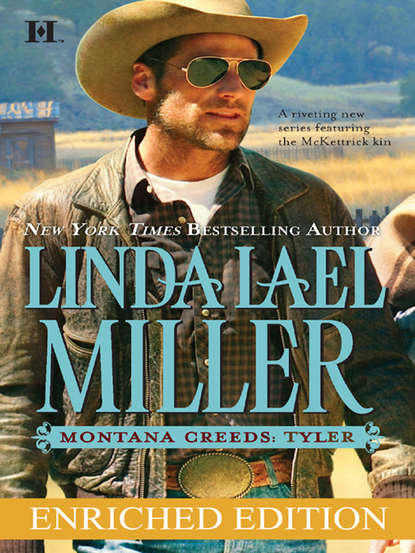

Montana Creeds: Tyler

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Do you ever read a newspaper?” Dylan countered, sounding semi-irritated now. Now there was a tone Tyler understood.

“No,” he snapped back. “My lips move when I read, and that makes me testy.”

“ Everything makes you testy, little brother.” Dylan paused, sighed. Went on. “Freida Turlow killed the girl—some kind of jealousy thing. And the drifter—well, that’s another story.”

“Those Turlows,” Tyler said, “are just plain loco.”

Dylan laughed again, but it was a raw, gruff sound, without a trace of humor. “Coming from a Creed, that’s saying something.”

In spite of himself, Tyler laughed, too.

“What brings you back to the home place, little brother?” Dylan asked. He was downright loquacious, old Dylan.

“Stop calling me ‘little brother,’” Tyler told him. “I’m a head taller than you are.”

“You’ll always be the baby of the family. Deal with it.” Dylan downshifted, with a grinding of gears, and they jostled up the lake road, toward Tyler’s cabin. “Answer my question. What are you doing here?”

Tyler let out a long sigh. “Damned if I know,” he admitted. “I guess I’m tired of the open road. I need some time to think a few things through.”

“What things?”

Again, Tyler’s temper, never far beneath the surface, stirred inside him. “What the fuck do you care?” he asked.

Kit Carson gave a fitful whimper from the backseat.

“I care,” Dylan said evenly. “And so does Logan.”

“Bullshit,” Tyler said flatly.

“Why is that so hard for you to believe?”

The cabin came in sight, nestled up close to the lake. It was more shack than house, his hind-tit inheritance from the old man, but Tyler loved the solitude and the way the light of the sun and moon played over that still water.

Logan, being the eldest, had scored the main ranch house when Jake Creed got himself killed up in the woods, logging, and Dylan, coming in second, got their uncle’s old dump on the other side of the orchard. That left Tyler in third place, as always.

Hind-tit.

Tyler unclamped his back molars, reached back to reassure the dog with a ruffling of the ears. Ignoring Dylan’s question, he asked about Bonnie instead.

“She’s fine,” Dylan answered.

He brought the truck to a stop in front of the log A-frame, and Tyler had the passenger-side door open before Dylan had shut off the engine. Kit Carson waited, shivering a little, with either anticipation or dread, until Tyler hoisted him down from the backseat.

“Thanks for the lift,” Tyler told his brother, reaching over the side of the truck bed for the kibble and the grub they’d picked up in town. Here’s your hat, what’s your hurry?

Dylan got out of the truck, slammed his door.

“Don’t you have things to do?” Tyler asked tersely. Kit Carson was sniffing around in the rich, high grass, making himself at home—and he was all the company Tyler wanted at the moment. Once inside, he’d prime the pump, build a fire in the antiquated wood cookstove and brew some coffee. Try to get a little perspective.

“I have all kinds of ‘things to do,’” Dylan answered, his mild tone in direct conflict with his go-to-hell manner. “I’m building a house, for one thing. Logan and I are back in the cattle business. But you’re at the top of my to-do list today, little brother. Like it or lump it.”

Tyler consulted an imaginary list, envisioning a little notebook, like the one his dad had always carried in the pocket of his work shirt, full of timber footage and married women’s phone numbers. “You’re at the top of mine, too,” he replied. “Trouble is, it’s a shit list.”

Dylan leaned against the hood of his truck, watching as Tyler started for the cabin, lugging the kibble under one arm and juggling two grocery bags with the other. Kit Carson hurried after him, though it was most likely the dog food he was after.

“Ty,” Dylan said, easy-like but with that steel undercurrent that was pure Creed orneriness, born and bred, “we’re brothers, remember? We’re blood. Logan and I, we’d like to mend some fences, and I’m not talking about the barbed-wire kind.”

“You’ve obviously mistaken me for somebody who gives a rat’s ass what you and Logan would like.”

Dylan stepped back from the truck, folded his arms. “Look,” he said, as Tyler passed him, headed for the front door of the cabin, “we were all messed up after Jake’s funeral—”

Messed up? They’d gotten into the mother of all brawls, he and Logan and Dylan, down at Skivvie’s Tavern. Wound up in jail, in fact, and gone their separate ways—after saying a lot of things that couldn’t be taken back.

Tyler shook his head, shifted to fumble with the doorknob. The thing was so rusted out, he’d never bothered with a lock, but that day, it whisked open and Kit Carson shot over the threshold, growling low, his hackles up.

Dylan was right at Tyler’s back, carrying his guitar case and duffel bag. “What the hell?” he muttered.

Somebody was inside the cabin, that was obvious, and Kit Carson had them cornered in the john.

“Whoa,” Tyler told the dog, setting aside the stuff he was carrying.

“Call him off!” a youthful voice squeaked from inside what passed as a bathroom. “Call him off!”

Tyler and Dylan exchanged curious glances, and Tyler eased the dog aside with one knee to stand in the doorway.

A kid huddled on the floor between the pull-chain toilet and the dry sink, staring up at Tyler with wild, rebellious, terrified eyes. Male, as near as Tyler could guess, wearing a long black coat, as if to defy the heat. Three silver rings pierced the boy’s right eyebrow, and both his ears and his lower lip sported hardware, too. The tattooed spider clinging to his neck added to the drama.

Tyler winced, just imagining all that needlework. Gripped the door frame with both hands, a human barrier filling the only route of escape, other than the tiny window three feet above the tank on the john. The kid glanced up, wisely ruled out that particular bolt-hole.

“I wasn’t hurting anything,” he said. His eyes skittered to Kit, who was still trying to squeeze past Tyler’s left knee and challenge the trespasser. “Does that dog bite?”

“Depends,” Tyler said. “What’s your name?”

The boy scowled. “Whether he bites me or not depends on what my name is?”

Tyler suppressed a grin. Aside from the piercings and the spider, he reckoned he and the kid were more alike than different. “No,” he said. “It depends on whether or not you stop being a smart-ass and tell me who you are and what the hell you’re doing in my house.”

“This is a house? Looks more like a chicken coop to me.”

Standing somewhere behind him, Dylan chuckled. He’d set Tyler’s guitar case and duffel bag down and, from the clanking and splashing, started working the pump at the main sink.

“Okay, Brutus,” Tyler said, looking down at the dog, “get him.”

Kit Carson looked up at him in confusion, probably wondering who the hell Brutus was.

“Davie McCullough!” the kid burst out, scrambling to his feet and, at the same time, trying to melt into the bathroom wall, which was papered with old catalog pages and peeling in a lot of places. “All right? My name is Davie McCullough! ”

“Take a breath, Davie,” Tyler told him. “The dog won’t hurt you, and neither will I.”