По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

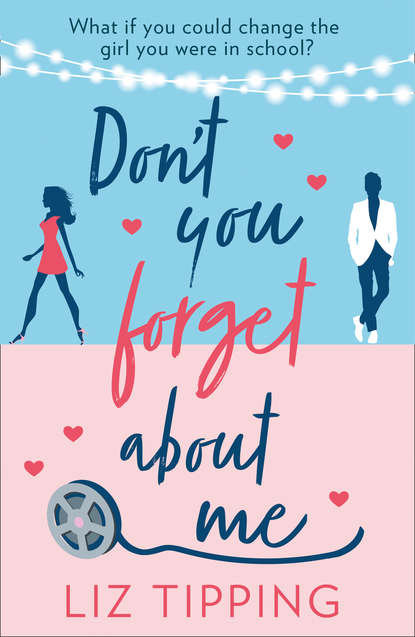

Don't You Forget About Me

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I felt like Stubbs could begin to do the things he enjoyed again. He was just lacking in confidence. Maybe it was the same for me. I got the impression from a few of the things he’d said that he’d been so busy supporting Kim in her career when he lived away, that he’d slotted into her life down south and there wasn’t much room for Stubbs to flourish. I studied him for a while and he looked distracted like something was troubling him. His face slightly screwed up. I think that’s what your face looks like when you are having a battered sausage revelation.

Stubbs could do whatever he wanted. We both could. We could both have our John Hughes moments, our scene at the end when everything was perfect. And I’d go to April’s stupid ball as well, even though it would be such a hard thing to do. Like Andie in Pretty in Pink, I needed them to know they didn’t break me.

Chapter Four (#ulink_953ff0f8-8e75-5ab5-93c9-59c9b88b7702)

I woke on Sunday feeling like I’d barely slept at all and my head was whizzing with thoughts of school reunions, Daniel Rose and disappointing school discos. I was shattered from too much wine and that vile cider and black. I was convinced I would go straight to sleep, but I lay awake for ages and everything came flooding back as though it was yesterday.

I’d made myself invisible nearly all the way through school, then when Daniel appeared suddenly I didn’t want to be invisible any more. I had tried so hard for no one to ever look my way and Daniel had noticed me anyway. He made me think it would be okay for people to see me.

By the time the Christmas disco came around, Daniel Rose had flirted with and asked out every girl in our class apart from me. I told myself I’d been foolish to think he’d even noticed me, but sometimes I caught him looking over in class and he spoke to me in detention every day. Verity said he was probably waiting to ask me to the disco. She thought he liked me too. We both walked home for weeks, saving up our bus fare so we could buy clothes for the Christmas disco, and I lived in hope that Daniel was going to ask me out. I was fed up of not joining in, not taking these moments for myself.

I walked into the hall where Daniel was standing near the door. I thought he might be about to come over and ask me out. Then I was jostled by one of April’s friends who laughed out loud and then muttered “bag lady” as she walked past. I hadn’t heard it in years and it cut deep. Bag lady. How could she be so cruel? This was the moment I had been waiting for, for Daniel to notice me and ask me out. I felt so vulnerable stood in front of all those people. Tears rolled down my face and I couldn’t speak. Daniel Rose was looking right at me. Was he going to save me from this humiliation with a kind word or a look? He looked down at the floor and walked away. I felt Stubbs pull my hand from behind. I wondered if he had heard the unkind words. I wasn’t sure, but I felt his pull and walked away with him.

The following day there were sniggers again, chattering about me barely out of earshot. I should have known not to draw attention to myself.

After that, I went back to being invisible again. It was easier that way.

*

When April had first invited us to the ball, I knew I had to go. I wanted to prove to everybody that all those years of hiding away meant nothing – that I was just as good as everyone else. I’d spent so long feeling invisible and trying to be average, I felt I’d never really had a chance to shine at anything and I hadn’t found my thing.

All the years of missing out on social activities meant I spent a lot of time at home watching films, experiencing all my important moments watching John Hughes films, not having any of my own. But it wasn’t too late to find out what my thing was.

I dragged myself to the convenience shop on the corner of the High Street, just before midday, to seek out some Sunday lunch. In the shop, I found myself browsing the Pot Noodles – such was my glitzy life. I bizarrely found myself wondering what April would be having for her lunch. Something expensive, most probably. April had made a success of things here in Broad Hampton whereas I couldn’t even make a Sunday lunch. I was pleading with Mr Sidhu because last week, I had made him promise never ever, ever to sell me a Pot Noodle on a Sunday again no matter how hung-over I was and how much I begged.

He folded his arms and shook his head slowly, resolutely. He wasn’t going to budge.

“Just this once,” I said, “then I am quitting.”

“This is the last time,” he said. “You said you were quitting. How about a nice microwave meal instead? Have a look in the freezer. I’ve got some nice frozen chicken dinners for you.”

He gestured to the chest freezer, which was half full of 10p freeze pops and the rest full of boxes covered in so many ice crystals you couldn’t really tell what they were.

I was peering in the freezer when I heard Stubbs.

“You won’t find a Pot Noodle in there, Cara,” he said, laughing. Judging by the grey sweatpants and white vest, I assumed he’d been for a run over the rec.

“Have you really been up at this hour running?” I said.

“It’s nearly lunchtime,” he said.

“Why do you do it though? Running?” I asked as he paid Mr Sidhu for his water.

Stubbs was never really a sporty type at school and here he was dressed just like Emilio Estevez. Perhaps Stubbs was now an athlete and had found his ‘thing’.

He shrugged. “Makes you feel good.”

“You should listen to your friend,” Mr Sidhu said. “Some fresh air, exercise, good food. Just what you need.”

I thanked Mr Sidhu for his unsolicited and unwelcome advice and me and Stubbs made our way out of the shop. But he had a point.

“So would you say it’s like your ‘thing’ now, being an athlete?” Maybe it could be my thing too? Then when I went to the ball, I could tell people how sporty I was and everyone would marvel at my athleticism. I wondered how long it would take for me to fully athleticise. More than a fortnight, I imagined.

“Why do I have to have a ‘thing’?”

“Like in The Breakfast Club,” I said. “It’s what makes them all cool. Can you teach me how to run in a fortnight?”

Stubbs laughed and stopped in his tracks, nearly spitting his water out.

“How did you get to thirty years old and not know how to run? You don’t know how to run! Have you heard yourself?”

“Well, obviously, I could run, but I don’t have special clothes or anything.”

“You are a moron, you know that, don’t you?” he said, grinning.

I gave him a gentle dig in the arm.

“Go on, please, show me how to run. I want to see if I’m an athlete. Maybe I could have been if I’d been able to afford to go to the clubs and buy the kits,” I said.

“Okay, if you really want to know how to run, meet me in the park later. And I will teach you the noble art of putting one foot in front of the other. And maybe how not to be such a moron.”

“I think I could totally do it. Being an athlete would suit me. Like Emilio Estevez in the film. Except not a wrestler because that would be weird, but yeah, you can show me how to do running later.”

He repeated everything back to me, sarcastically. “You want to be an athlete, like Emilio Estevez in the film? And you want me to show you how to do running?”

Now he said it like that, it did sound a bit stupid, but I persisted and pretended it was perfectly normal. “Yes please,” I said. “You can help me because you are good at everything. Even PE.”

Being from our estate hadn’t seemed to hold Stubbs back in exactly the same way it did with me, but I still felt he hadn’t achieved all he could. He’d always seemed to rise above any teasing, laughing it off or batting it back with witty remarks.

“PE?” Stubbs laughed. “Yeah, well, I don’t really call it PE any more, you know. I tend it call it exercise, like normal people do. But okay, whatever, Dunham. I’ll see you later.”

I phoned Verity as soon as I got in.

“I’m going to be an athlete,” I said. “It’s going to be my thing. Stubbs is going to teach me how to run. Want to come?”

“I’d love to but it’s Sunday and I have to watch Frozen four hundred times. Why are you going to be an athlete, by the way?” she said as an afterthought.

“So I don’t look like a loser at the school reunion. It’s part of finding my thing; then I’ll go to the school reunion, Daniel Rose will find me scintillating and magnetic and I’ll have my John Hughes moment and then I can get on with life. It will be a turning point, like in a film.”

“Right. Well I’m glad you’ve sorted that out. You’re going for a run in the park with Stubbs and then your life is going to magically change?”

“Exactly,” I said. Listening to my plan remixed with Verity’s cynical words didn’t make it sound the most convincing, but it seemed as good a place to start as any. Besides I thought it would be fun going to the park with Stubbs. I still wasn’t fully convinced the athlete’s life was for me. Maybe I needed to up my game and rethink my nutrition? I stared at my Pot Noodle on the kitchen worktop and swiped it away into the bin. I was having a Pot Noodle moment to go with the battered sausage revelation.

*

“Are you still hung-over? You’re hung-over, aren’t you?” Stubbs looked like a proper runner, alternately stretching his arms across his back and stretching out his thighs, which I may have by accident had a look at for slightly too long.

“No,” I insisted. I gulped down some water and squinted in the sunlight.