По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

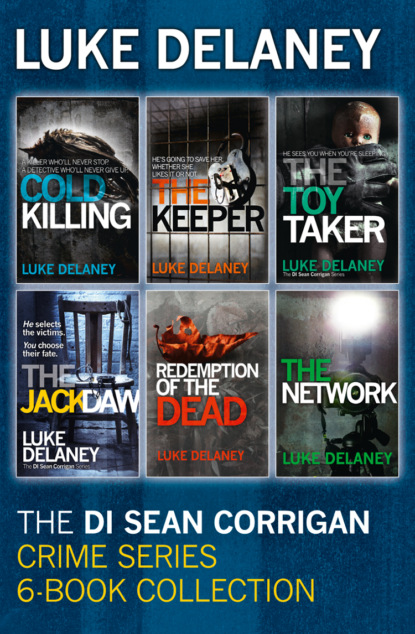

DI Sean Corrigan Crime Series: 6-Book Collection: Cold Killing, Redemption of the Dead, The Keeper, The Network, The Toy Taker and The Jackdaw

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Hellier pulled the smaller envelope from his jacket pocket, opened the flap and shook the contents out on to the table − a silver key. He couldn’t help but look around him as he put the key into the lock. It was stiff, causing him to feel a stab of panic as he jiggled it, eventually turning the lock and opening the box. Slowly he lifted the lid and peered inside. The box was as he had left it. He ignored the rolls of US dollars and pushed the loose diamonds out of the way, flicking a five-carat solitaire to one side as if it was a dead insect, until he found what he was looking for − a scrap of ageing paper. He lifted it closer to the light and examined it, relieved to see the number was still visible after all this time. He smiled, and spent the next ten minutes committing the number to memory. He ignored the first three digits – the outer London dialling code – but he repeated the remainder of the number over and over until he was sure he would never forget it.

‘Nine-nine-one-three. Two-zero-seven-four. Nine-nine-one-three. Two-zero-seven-four.’

Sean read through the files from General Registry. He’d found it difficult to concentrate at first, the logistical problems of the investigation severely hindering his free thinking, but as the office grew quieter he was able to lose himself in the files.

He’d already rejected several. They were all extremely violent crimes that remained unsolved, but they just didn’t feel right. Too many missing elements.

He picked up the next file and flipped open the cover. The first thing he saw was a crime-scene photograph. He winced at the sight of a young girl, no more than sixteen, lying on a cold stone floor, her dead hands clutching her throat. He could see she was lying in a huge pool of her own blood and guessed her throat had been cut.

He leaned into the file. The photographs spoke to him. The victim spoke to him. His nostrils flared. This one, he thought to himself. This one. He flicked past the photographs and began to read.

The victim was a young runaway. Came to London from Newcastle. Parents reported her missing several days before her body was found. Neither parent considered as a suspect. No boyfriend involved. No pimp under suspicion. Her name, Heather Freeman. Body recovered from an unused building on waste ground in Dagenham. No witnesses traced.

Sean rifled through the papers to the forensic report. It was ominously short. No fingerprints, no DNA, no blood other than the victim’s. The suspect had left no trace of himself other than one thing: footprints in the dust inside the scene. They were striking only because of their lack of uniqueness. A plain-soled man’s shoe, size nine or ten, apparently very new with minimal scarring.

‘Jesus Christ,’ he whispered.

Sean checked the date of the murder. It predated Daniel Graydon’s death by more than two weeks. ‘You have killed before, you had to have, but how many times?’ His head began to thump. He searched for the name of the investigating officer and found it: DI Ross Brown, based on the Murder Investigation Team at Old Ilford police station. He bundled together his belongings and, taking the file with him, headed for the exit. He’d phone DI Brown once he was on his way.

Hellier walked along Great Titchfield Street, still in the heart of London’s West End shopping area, although it was a lot quieter. He soon found a phone booth and pumped three pound coins into the slot. He heard the dialling tone and punched the number keypad. Zero-two-zero. Nine-nine-one-three. Two-zero-seven-four.

The dialling tone changed to a ringing one. He waited only two cycles before it was answered. The person on the other end had clearly been expecting a call. Hellier spoke.

‘Hello, old friend,’ he said mockingly. ‘We have much to discuss.’

‘I’ve been waiting for you to call,’ the voice answered. ‘I expected it sooner.’

‘Your friends took my contact book,’ Hellier told him, ‘and you’re not listed in the phone book or with Directory Enquiries. Makes you a difficult person to find.’

‘The police have taken a book off you with my number in it?’ The voice sounded strained. ‘How the hell did you let that happen?’

‘Calm down.’ Hellier was in control. ‘All the numbers in the book were coded. No one will know it’s yours.’

‘They’d better not,’ the voice said. ‘So if they’ve got the book, how did you find my number again?’

‘You gave it to me, don’t you remember? When you first came begging to me. Cap in hand. You wrote it on a piece of paper. I kept it. Thought it might come in useful one day.’

‘You need to get rid of it. Now,’ the voice demanded.

Hellier wished he and the voice were face to face. He’d make him suffer for his insolence. ‘Listen, fucker,’ he shouted into the phone. A passer-by glanced at him, but quickly looked away when he saw Hellier’s eyes. ‘You don’t tell me what to do. You never fucking tell me what to do. Do-You-Understand-Me?’

There was silence. Neither man spoke. It gave Hellier a few seconds to regain his composure. He pulled a handkerchief from his trouser pocket and dabbed his shining brow. The voice broke the silence.

‘What do you want me to do?’

‘Get Corrigan to call his dogs off,’ Hellier replied.

‘I don’t think I can do that. If I could think of any way … But I swear I don’t have that sort of pull.’ The voice was almost pleading.

‘You’re a damn fool,’ Hellier snapped. ‘Just wait for me to call you. I’ll think of something.’ He hung up.

Feeling better now, he rolled his head and massaged the back of his neck. He glanced at his watch. Time was passing. He needed to get back to work.

Sally sat in a side office at the Fingerprint Branch at New Scotland Yard. A tall slim man in his mid-fifties entered the room nervously. Sally stood and offered her hand. ‘Thanks for seeing me so quickly.’

‘No problem at all,’ said IDO Collins. ‘How can I help?’

Sally sucked in a lungful of air and began to explain herself. ‘This is a sensitive matter, you understand?’

‘Of course,’ Collins reassured her.

‘On the phone you said you couldn’t find Korsakov’s fingerprints. So what I need to find out is how the fingerprints of a convicted criminal could go missing.’

Collins smiled and shook his head. ‘Not possible. You can’t remove files from the computer database.’

‘Before that,’ Sally said. ‘Assume they went missing from the old filing system. Possible?’

‘Well, I suppose so.’ Collins began to chew the side of his thumb. ‘But they could only go missing for a period of time.’

‘Meaning?’

‘Well, on the old system, officers and other agencies would sometimes ask to look at sets of prints. Mostly they would view them here at the Yard, but occasionally they would have to take them away. For example to compare them with a person the Immigration Service had doubts about, or to compare them with a prison inmate if the Prison Service suspected funny business. Somebody trying to serve a sentence on behalf of somebody else. It does happen, you know. Usually for money, sometimes out of fear.’

‘Or to get away from the wife and kids?’ Sally half-joked.

‘Yes. Probably. I wouldn’t know.’ Collins laughed a little. He still sounded nervous. ‘Anyway. Prints might be taken away, but if they weren’t returned quickly, within a few days, we’d chase after them. We’d always get them back. Always. We simply wouldn’t stop pestering until they were returned. They’re too important to allow them to disappear.’

‘Then perhaps you can explain how this set vanished?’ Sally slid a file across the desk. ‘Stefan Korsakov. Convicted of fraud in 1996. He definitely had prints taken when he was charged. No mistake. Prints that you’re telling me have since disappeared.’

Collins looked shocked, but recovered quickly and smiled. ‘A clerical mistake. Give me a minute and I’ll search for them myself.’

She knew it made sense to double check. ‘If it’ll make you feel better, then it’ll make me feel better. I’ll be in the canteen. Give me a shout when you’re finished.’

DI Ross Brown waited at the old murder scene for Sean to arrive, the police cordon tape flapping loosely in the mild breeze, tatty and spoilt now.

It was getting late, but he didn’t mind waiting. His investigation had not been going well − stranger attacks of this type were extremely difficult to solve quickly. Unless you were out to make a name for yourself, they were every detective’s worst nightmare. And with only three years’ service remaining, DI Ross Brown wasn’t out to make a name for himself. If he thought Sean could help his case, he’d wait all night.

Sean found his way to Hornchurch Marshes and drove through the unmanned entrance to the wasteground. A single road wound its way over the desolate and oppressive land to a small outbuilding. Sean could see a tall, well-built man standing outside. He parked next to DI Brown’s car and climbed out. Brown was already moving towards him, his hand outstretched.

‘Sean Corrigan. We spoke on the phone.’

Ross Brown wrapped a big hand around Sean’s. His grip was surprisingly gentle. ‘Good of you to come all this way out east,’ he said.

‘I just hope I’m not wasting your time,’ Sean answered.

DI Brown pointed to the outbuilding. ‘She died in there. She was fifteen years old.’ He looked sad. ‘She’d run away from home. The usual story. Mum and Dad split up, Mum gets a new man, kid won’t accept him and ends up running away to London − straight into the hands of some sick bastard.

‘It’s not easy to get the homeless to talk,’ he continued, ‘to get their trust. But a couple of her friends have provided us with details of her last movements.