По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

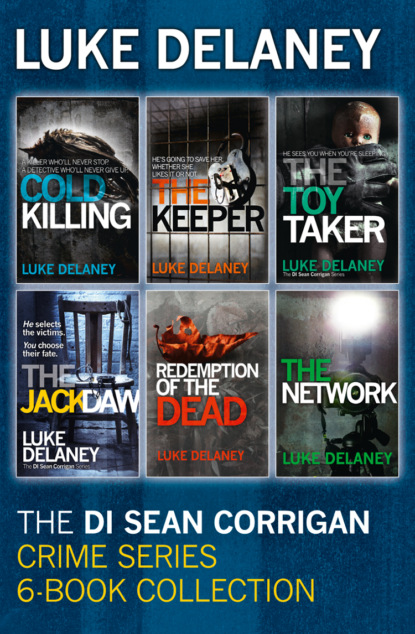

DI Sean Corrigan Crime Series: 6-Book Collection: Cold Killing, Redemption of the Dead, The Keeper, The Network, The Toy Taker and The Jackdaw

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘We’re pretty certain she was abducted in the King’s Cross area on the same night she was killed, about two weeks ago, give or take. We canvassed the area, but no one witnessed the abduction − our man is apparently extremely cautious and fast.

‘We tried to get the media interested, but we only got minimal coverage. It’s difficult to compete with suicide bombers, and they like victims to be the nice, top-of-the-class type, not teenage runaways.

‘The killer drove her to this waste ground. He took her into this abandoned building, stripped her, and then he cut her throat. One large laceration that almost cut the poor little cow’s head off.’

Sean could see Brown was disturbed. No doubt the man had teenage daughters of his own. The nearby giant car plant dominated the horizon. It all added to the feeling of dread in this place. ‘Poor little cow,’ Brown repeated. ‘What the hell must she have been thinking? All alone. Made to strip. There were no signs of sexual abuse, but we can’t be sure what he did or didn’t make her do. Fucking animal.’

‘The murder of Daniel Graydon occurred six days ago,’ Sean said without prompting. ‘His head was caved in with a heavy blunt instrument, not recovered. He was also stabbed repeatedly with an ice pick or similar, not recovered either. He was killed in his own flat in the early hours. No sign of forced entry. He was a homosexual and a prostitute.’

Brown frowned. He couldn’t see much of a connection to his investigation, if any. ‘Doesn’t sound like my man. Different type of victim, murder location, weapon used. I’m sorry, Sean. I don’t see any similarities here.’

‘No,’ Sean said, holding up a hand. ‘That’s not where the similarity lies.’ He began to walk to the outbuilding. DI Brown followed him.

‘What then?’ Brown asked.

‘The only usable evidence from our scene were some footprints in the hallway carpet. They were made by a man wearing a pair of plain-soled shoes with plastic bags over them. The forensic report said you recovered footprints.’

‘Yes,’ Brown said. ‘Inside the outbuilding.’

‘And no other forensic evidence?’ Sean asked.

‘Is that why you’re here?’ DI Brown asked. ‘Because neither of us have any forensic evidence, other than a useless shoeprint?’ Sean’s silence answered the question. ‘Then I guess we’re both in the shit,’ Brown continued, ‘because if you’re right and these murders are connected, then this is a really bad bastard we’re after here and he’s absolutely not going to stop until someone stops him.’

Sean’s phone interrupted him before he could reply. It was Donnelly. ‘Dave?’

‘Guv’nor, surveillance is in place at Butler and Mason, and guess who’s back?’

‘He’s at work?’

‘No mistake. I’ve seen him myself through the window. He’s not hiding.’

‘Okay. Stay on him. I’ll call you later.’ He hung up.

What the hell are you up to now? And where have you been that you didn’t want us to see?

‘Problem?’ Brown asked.

‘No,’ Sean answered. ‘Nothing that can’t wait.’

Sally saw Collins enter the canteen and gave a little wave to attract his attention. He sat opposite her, carefully placing an old index book on the table.

‘From a time before computers,’ he told her. ‘I’ve double checked both the computer system and searched manually, as well as checking the old records on microfiche. We have nothing under the name of Korsakov.’

‘Which means?’ Sally asked.

‘Well, normally I would have said that you were mistaken. That Korsakov’s prints could never have been submitted.’

‘But …?’

‘But I have this.’ He patted the index book. ‘This is a record of all fingerprints that are removed from Fingerprint Branch. We still use it as a back-up for our new computer records, and this way we actually get the signature of the removing party, which helps ensure their safe return. This volume goes back to ninety-nine.’

Collins went to the page showing all the fingerprints of people whose surnames began with the letter K that were removed that year. It was a comparatively short list. Fingerprints were rarely removed.

‘Here,’ he pointed. ‘On the fourteenth of May 1999, fingerprints belonging to one Stefan Korsakov were removed by a DC Graham Wright, from the CID at Richmond.’

‘So they were here?’ Sally asked.

‘They must have been.’

‘But this DC Wright never returned them?’

‘That’s the bit I don’t understand,’ said Collins, frowning. ‘They were returned. Two days later by the same detective, along with the microfiche of the prints, which he’d also booked out.’

‘Then where are they?’

‘I have no idea,’ Collins admitted.

Sally paused for a few seconds. ‘Could someone have simply walked in here and taken the prints and microfiche?’

‘I seriously doubt it. The office is always manned and all prints and fiches are locked away. Only someone who worked in the Fingerprint Branch would have that level of access.’

Why the hell would someone from Fingerprints want to make Korsakov’s records disappear? Had he corrupted someone there? Paid them for a little dirty work? But in May of 1999 he was still in prison, so how could he possibly have known whom to approach? No, Sally decided. Something else.

‘When fingerprints are returned, are they checked?’ she asked. ‘Before being accepted.’

‘A quick visual check, no more,’ Collins told her.

‘And the microfiche?’

‘No. That wouldn’t have been standard practice. So long as the fingerprints were in good order, that would have been that.’

Sean and Brown moved into the outbuilding. There was still light outside, but inside it was dim and damp. Sean could clearly see the last remains of that horrific night: a large circular bloodstain in the middle of the floor. It was rusty brown now. The inexperienced eye would have thought it nothing. He sometimes wished his eyes could be so innocent.

The arterial spray marks went from Sean’s left to right across the room. They’d almost hit the wall over twelve feet away. The detectives moved around slowly in the gloom. The scene had long since been examined and any evidence taken away, but Sean studied it closely nonetheless. He knew nothing would have been missed, but that wasn’t why he was there. He was seeing that night through the victim’s eyes. Through the killer’s eyes.

Brown broke the silence. ‘We know she was on her knees when he cut her,’ he said solemnly, ‘from the distance her blood travelled and the body’s final resting position. He pulled her head back and then slit her throat.’ Brown obviously didn’t enjoy recounting their findings. ‘You really think these murders could be linked?’

Sean didn’t answer. He knelt down. This was how Heather last saw the world. ‘We have a suspect,’ he announced suddenly.

‘A suspect?’ Brown asked.

‘Yeah,’ Sean said. He could feel the clouds lifting from his mind. Could see things he’d never considered before. Standing on the spot where Heather Freeman had died fired his mind, his imagination, the dark side he buried so deep. ‘James Hellier,’ Sean continued. ‘Up until this point he’s been hiding from us. Hiding behind a mask of respectability. A wife and children. A career. But he’s out now. He’s showing himself to us.

‘The gender of the victims doesn’t matter to him. Male, female – makes no difference. It’s not a matter of sex with Hellier. It’s about power. About victimization. The gender is coincidental. Two young and vulnerable victims. Easy targets.’

‘Why’s he not bothered about leaving his footprints,’ Brown asked, ‘if he’s so damn careful where everything else is concerned?’

‘No.’ Sean spoke softly. ‘He’s extremely concerned about footprints. He’s probably experimented with dozens of methods, maybe even hundreds, but each time he comes up with the same conclusion. No matter what he tries, no matter what shoes he wears, what surface he walks on, he nearly always leaves some type of print. Even if it’s the slightest impression in a carpet, like in Daniel Graydon’s flat.