По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

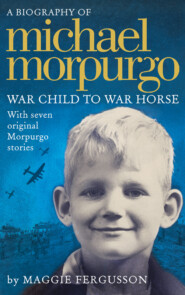

Michael Morpurgo: War Child to War Horse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In November 1945 Kippe caught the train up to London and she and Jack spent the evening alone together. By the end of the year they were engaged in what Jack later described as a game of ‘Let’s pretend’ – ‘but we were not children, we were in love’.

What happened over the next few weeks can be pieced together from a slim file of correspondence which remains, more than sixty years on, so distressing to Michael that he has never read it in full. Jack Morpurgo was cleverer than Kippe, and he knew it. His letters to her, typed on foolscap in faultless mandarin prose, are exercises in intellectual bullying. He bombards her with arguments until he has her boxed in on every side. Tony Bridge, he insists, is a mere ‘base-wallah’ who has seen no real action. He is utterly undeserving of a wife like Kippe, whom Jack compares to Cleopatra. He flatters Kippe, quoting Keats to Fanny Burney, ‘You have ravished me away by a Power I cannot resist …’, but he also hints that youth is not on her side, and states baldly that he is ‘not prepared to wait indefinitely’. When, briefly, Kippe summons up the strength to break off relations with him, he writes daily to his ‘Lost Darling’, protesting that she has condemned him to ‘an eternity of bleakness’ – yet slipping in a sly reference to Jean Lindsay, a pretty nurse with whom he spent time in Abyssinia, and who has been in touch and wants to see him.

Kippe’s handwritten responses to Jack are, by contrast, short and simple, and filled with self-denigration and remorse. She begs his forgiveness for her ‘failings’ and her ‘selfishness’, for her inability to express herself – ‘it’s pretty poor to be able to say so little so stupidly’ – and to see her way forward. She longs for guidance and comfort. Jack is sparing with his sympathy. ‘You have this marvellous capacity for taking upon your own shoulders the burdens of all the world, and for blaming none but yourself for the mishaps that occur to others,’ he concedes, but he warns that her misery and indecision will be causing damage to Pieter and Michael. And when Kippe admits that, in desperation, she has written a ‘muddled letter’ to Tony Bridge telling him what is afoot, Jack puts her swiftly into checkmate. He and Kippe cannot now stop seeing one another, he argues, because ‘any break in our relations implies acceptance of some guilt, and will imply that to your husband’. Nor can Kippe any longer contemplate a future with Tony Bridge, who, knowing of her feelings for Jack, ‘will pass his days with doubts’.

On receiving Kippe’s ‘muddled letter’ Tony was granted compassionate leave. He made a painful progress back to England – Basra to Baghdad, Baghdad to Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv to Cairo, Cairo to Alexandria, across the Mediterranean to France, and, finally, by steamer into Newhaven. On Friday 1 February 1946 he and Kippe were reunited at the Rembrandt Hotel in Knightsbridge.

They travelled together to Suffolk, and for a week bicycled around Blythburgh, Walberswick, Southwold, Tony hoping that, surrounded by silence and sea breezes, by tall churches, fluent countryside and early spring light, they might somehow recover what they seemed to have lost. They returned to the Eyrie, and for most of that spring they remained together. But the atmosphere was fraught and Kippe was still in touch with Jack. On 4 April, having found Kippe in tears in Tony’s arms, Emile Cammaerts sent Jack a letter, begging him courteously but firmly to leave his daughter alone. ‘I don’t know whether you realize what a terrible strain your present relationship with Catherine imposes upon Tony,’ he wrote. ‘I feel certain that he will not be able to stand it much longer. He is no longer the cheerful and easy-going man we used to know.’ It was no good. Back in London Kippe and Jack went to see a divorce lawyer and, as Jack put it, ‘prepared suitable evidence for inspection by a detective on an appointed day’.

It was to be, by today’s standards, a brutally thorough separation. In the face of fierce opposition from his parents, who were about to lose their only grandchildren, Tony decided that it would be best for his sons if he removed himself completely from their lives. He was, after all, through no fault of his own, a complete stranger to them.

Both sons now speak of his decision with defensive pride: ‘It was,’ says Pieter, ‘a very brave thing for him to do, to give us up. He thought, and I’m sure he was right, that it would be less confusing for us.’ Michael compares Tony to Gabriel Oak – ‘a man who didn’t know the meaning of possessiveness or selfishness’. But Tony did not regard his actions as either brave or noble: ‘It was,’ he wrote towards the end of his life, ‘just the way it had to be.’ After bleak attempts to reignite his acting career in the West End, he emigrated to Canada, changed his name to Tony van Bridge, and eventually found work with Sir Tyrone Guthrie in Stratford, Ontario.

Despite all he had suffered, Tony remained, in a part of himself, devoted to his ‘Kate’. In his 1995 memoir, Also in the Cast, the pages about her glow. ‘I am glad that Kate and I married,’ he insists; and the reader cannot help but feel that the urge to set down those words for posterity was his chief motive in writing the book.

In November 1945, the month that Kippe’s affair with Jack Morpurgo began in earnest, the film Brief Encounter was released in British cinemas. We all know the story: a man and a woman, middle-class, in early middle age and married, meet by chance on a suburban railway station and fall in love. After much humiliation, guilt and anguish – played out against the strains of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2 – they agree to part. So compelling were the performances by Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson that rumours flew about that they must genuinely be having an affair. But what impressed the Times critic was not so much the acting as the ‘heroic integrity’ at the centre of the film. In overriding their passions and returning to their dull but dependable spouses, the couple had, in the end, done ‘the right thing’.

All over Britain the opposite was happening. Since the end of the First World War divorce rates had soared. By the middle of the Second World War they seemed to be out of control. In October 1943, the month that Kippe gave birth to Michael, the archbishops of Canterbury and York had spoken out jointly against ‘moral laxity’, urging Christians to remember that promiscuity and adultery were sins that degraded personality, destroyed homes, and visited ‘years of terrible suffering’ on innocent children. But the divorce rates rocketed again that year and the next. In 1945, 15,634 couples divorced; and by the time Kippe and Tony’s decree nisi was granted the following year the number had nearly doubled to 29,829 – a misleadingly low figure, in fact, as by the middle of the year there were more than 50,000 service men and women waiting for divorces, and the Attorney-General had been forced to appoint thirty-five new legal teams to process their cases.

Behind these statistics lay innumerable tales of grief and heartache. Few divorces can have been less acrimonious than Kippe and Tony’s. It was, as Tony later wrote, ‘quiet and unsensational’. But it was, even so, ‘full of suffering on both sides’; and it left Kippe with a burden of guilt that she would carry to the grave.

She had inflicted great pain not just on Tony, whose decency and acquiescence can only have made her feel worse, but also on her parents-in-law. By running off with Jack Morpurgo she had proved all their misgivings about her well-founded, as well as depriving them of access to their only grandchildren. For weeks Arthur and Edith Bridge fought their son’s decision to give Kippe custody of the boys. She cannot have been unaware of their distress.

Then there were her own parents. Both Emile and Tita were children of broken marriages, and both, as a result, had an almost pathological horror of divorce. Ever since his father’s suicide, Emile had been haunted by the notion that there was ‘bad blood’ in the Cammaerts family and that it might one day resurface. On hearing the news that Kippe was to marry Jack, Jeanne remembers, Tita clung to the arms of her chair until her knuckles turned white, while Emile muttered, ‘I’ll kill that boy.’

They pleaded with Kippe to reconsider, employing all the arguments that Emile would later publish in a treatise on marriage, For Better, For Worse: adultery was ‘a sin’; second marriages were ‘sham marriages’; it put a child’s soul in danger to witness ‘division in the very place where union should prevail’. But, as her mind was made up, the chief effect of their pleading was to make Jack Morpurgo determined that they would play very little part in his and Kippe’s future. Though he generally disliked bad language, he referred to Tita simply as ‘the bitch’, and visited the Eyrie as seldom as possible. When he and Kippe finally married, in Kensington Register Office on 16 July 1947, not a single member of the Cammaerts family was present.

Kippe was forced to turn from her own family to the Morpurgos. Shortly after the marriage, she and Jack moved from his flat in Clanricarde Gardens, Notting Hill Gate, to 84 Philbeach Gardens, near Earls Court. The tall, terraced house was somewhat beyond their means, so Jack’s two spinster, schoolmistress sisters, Bess and Julie, moved in with them to help pay the bills and look after the boys. They were to remain a part of the household for the next quarter of a century, a Laurel and Hardy pair – Julie, who had been jilted when she was twenty-one, delicate and emotionally fragile; Bess big-hearted and controlling.

It was Bess who was deputed to take Pieter and Michael for a walk one afternoon, and to explain to them that Jack was now their father. A memory of their conversation remains with Michael, fragmentary but crystal-clear. ‘We were on a railway bridge. I must have said something about my father, and Bess said, “Well, you’ve got a new father now, you know.” And a train came by, and the steam came up in my face. And it just felt quite strange.’

Jack, in fact, never formally adopted Pieter and Michael; but he was determined to expunge the memory of Tony Bridge, and the boys implicitly understood that their real father must not be mentioned. From the summer of 1947 onwards, they took Jack’s surname. ‘No one ever said, “Jack is your stepfather,”’ Michael remembers. ‘And when my mother had two more children, Mark and Kay, no one talked about half-brothers and half-sisters. We were the Morpurgos: that’s what they told the outside world. We children were part of that story; that sham.’

Pieter was just five at the time of the divorce, and had recently learned to write out his full name, PIETER BRIDGE. One of his earliest memories is of being told that he was a Bridge no longer, and of toiling over the new letters M-O-R-P-U-R-G-O. But visitors had only to look at Pieter to see that he was not a Morpurgo. He was extraordinarily like his true father; a constant, vexing reminder to Jack of the man he had wronged. Like Farmer Tregerthen in Michael’s story ‘Gone to Sea’, Jack was ‘not a cruel man by nature, but he did not want to have to be reminded continually of his own inadequacy as a father and as a man’. From the start, he was unreasonably hard on Pieter, whom Jeanne describes as a ‘sensitive, shivering child’, and Michael was aware of being unfairly favoured.

Michael and Pieter outside 84 Philbeach Gardens.

Pieter and Michael, 1948.

Perhaps Kippe, too, was unsettled by Pieter’s likeness to Tony; perhaps, because he was nervous and easily upset, he fuelled her guilt. Michael, by contrast, was a robust, sunny toddler, and with his mother, as with Jack, he had the closest bond. He remembers walking with her, hand-in-hand, through the smog that descended on London like a manifestation of post-war gloom. He remembers the thrill of being allowed to take charge of the ration book when they shopped together at the local International Stores, where he committed his first felony, slipping into his pocket a model Norman soldier with an orange tunic and an irresistible hinged helmet. He remembers stopping with her to talk to the weepy-eyed, skewbald milk-cart horse, Trumpeter, which used to stand shifting from foot to foot in Philbeach Gardens, munching from the sack of hay round his neck, giving off what seemed to Michael a fascinating odour of fur and sweat and dung.

But most vivid of all are his memories of bedtime, when Kippe would sit at the end of his bed and read to him. She read from Aesop’s Fables, Masefield and de la Mare, from Belloc, Longfellow, Lear and Kipling. She had a way of making imaginary characters and places come alive, of conveying the music and joy and taste of language:

Then Kolokolo Bird said, with a mournful cry, ‘Go to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees …’

Michael rolled the words around on his tongue like sweets. When he was three, his mother found him rocking to and fro in his bed, chanting ‘Zanzibar! Zanzibar! Marzipan! Zanzibar!’

Story-time over, Kippe would leave the door slightly ajar to let in a chink of light. The smell of her face-powder lingered in the room.

Sometimes there could be about Kippe an almost reckless joie de vivre. When one afternoon Pieter and Michael locked themselves into their fifth-floor bedroom while they were supposed to be resting, she shinned undaunted up a drainpipe, ignoring Jack’s protests, and climbed in through their window to rescue them. When visitors came to the house she shone. ‘As she opened the front door,’ Michael remembers, ‘it was as if she was walking on to a stage – beautifully dressed and made-up, charming, sparkling.’

But when the visitors left she tended to collapse, reaching for her cigarettes and smoking almost obsessively. And sometimes for days on end a sadness – what Pieter calls ‘a wondering’ – would settle upon her, and she became quiet and unreachable. Twice a year she would take Pieter and Michael on a bus to Twickenham to visit their paternal grandparents in their neat, modest, semi-detached house in Poulett Gardens. Michael remembers the uncomfortable formality of these visits – ‘the scones, the clinking of spoons on teacups’ – and the awkwardness as the conversation turned to Tony, his grandparents bringing out photographs and press clippings to show to the boys. On the way home, and for days afterwards, Kippe was silent. Michael knew that to ask questions would upset her further, so he too remained silent, aware simply that ‘ours was a family which had at its heart a tension’.

In the wider world, too, he was becoming aware of complexity and shadows. The area around Philbeach Gardens had been heavily bombed in the Blitz, and the house next to number 84 completely destroyed. The cordoned-off bomb site was reachable via the cellar, and Michael particularly liked to play here alone. ‘It was my Wendy house, I suppose. A rather tragic Wendy house.’ Among the weeds and crumbling walls were remnants of life – bits of cutlery, a chair, an iron bedstead – evidence that in the very recent past ‘there had been this terrible trauma’ for the family that had lived there.

Michael, 1948.

School, when it came, confirmed his sense that the world could be harsh. At three, Michael was taken to a playgroup in the hall of St Cuthbert’s, Philbeach Gardens: a cosy, eccentric set-up, where the lady in charge kept order by issuing the children with linoleum ‘islands’ on which they would be asked to sit if they threatened to become unruly. At five, he moved on to the local state primary school, St Matthias, across Warwick Road. It seemed a cavernous, grim place to a small boy, with painted brick walls as in a prison or hospital, and windows so high that if a child tried to look out all he could see were small segments of sky. There was one magical element. Beneath the school lived a community of refugee Greek Orthodox monks: long, black-robed creatures who glided soundlessly in and out of a dark chapel full of glowing lanterns. But within the school itself the children were coaxed into learning through fear. Mistakes were met with a thwack of the teacher’s ruler, either on the palm of the hand, or, more painfully, across the knuckles. Michael found himself frequently standing in the corner. Books and stories were suddenly filled with menace – ‘words were to be spelt, forming sentences and clauses, with punctuation, in neat handwriting and without blotches’. He developed a stutter, his tongue and throat clamping with terror when he was asked to read or recite to the class; and he began to cheat, squinting across to copy from brainy, bespectacled Belinda, who shared his double desk, and with whom he was in love.

So it came as a relief when, just after his seventh birthday, plans were made for Michael to leave St Matthias and join Pieter at his prep school in Sussex. Kippe took him on a bus to Selfridges, and he remembers the delight of being measured up, of being the centre of attention, of watching his ‘amazing’ uniform (green, red and white cap; blazer ‘like the coat of many colours’; rugby boots; shiny, black, lace-up shoes; socks; shorts; shirts and ties) piling up on the counter – ‘all for me!’ He had remained, despite everything, a happy child, ‘very positive, full of laughs, a bit of a show-off’, and the prospect of prep school was thrilling. ‘I was really looking forward to it,’ he says. ‘I had no idea what was in store.’

It can be uncomfortable when family stories believed to be true are revealed as myth. When Maggie told me the truth about my uncle Pieter’s death, it took a while to sink in. The story I’d believed for nearly seventy years had entered deeply into my imagination. So, in a different way, had the letters that Jack Morpurgo and my mother wrote each other when they fell in love – though I’ve not read them all. I wanted to work both Uncle Pieter and those letters into a story. As I turned it over in my mind it began to take the form of a letter itself – a confessional story/letter.

Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble (#uacfd6f7b-2c31-531a-a2d7-3dcd63ddbf77)

To my mother, Kippe

Do you remember? You used to read to us every night, every night without fail. For both of us, Piet and me, this time just before bed was an oasis of warmth and intimacy. The taste of toothpaste still reminds me of those precious minutes alone with you, our bedtime treat. We’d climb into the same bed, browsing the book together before you came, longing to hear the sound of your footfall on the stairs. Sometimes I’d fall asleep before you came but would always wake for the story. You read to us only those stories and poems that you loved, often in a hushed voice as if you were confiding in us, telling us a secret you’d never told anyone else. We still love those stories and poems to this day, over sixty years later, but in my case with one exception.

Everything else you read us I simply adored. I never wanted your story-time to end. ‘The Elephant’s Child’ from Kipling’s Just So Stories was my favourite. Piet’s was ‘The Cat that Walked by Himself’. We both knew them off by heart. And then sometimes you’d read a poem by Masefield or de la Mare. It could be ‘The Listeners’ –

‘Is there anybody there?’ said the Traveller,

Knocking on the moonlit door;

And his horse in the silence champed the grasses

Of the forest’s ferny floor …

Or maybe ‘Cargoes’, with all those wonderfully mysterious and musical names: ‘Quinquireme of Nineveh from distant Ophir’. Or ‘Sea-Fever’:

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky …

I may not always remember which poet wrote which poem, but I remember the poems, every line of them; and your voice reading them. And I mustn’t forget Edward Lear’s nonsense poems, those ludicrous limericks that made us all laugh so much.

There was an Old Man with a beard,

Who said, ‘It is just as I feared! –

Two Owls and a Hen, four Larks and a Wren,

Have all built their nests in my beard!’

We all thought that the old man in question had to be your daddy, or Grad as we called him, who had a bushy white beard that smelt of pipe tobacco. I used to sit on his lap sometimes and explore the depths of his beard with my fingers, searching for any birds or birds’ nests that might be there, but they never were. When I asked Grad once why there were no birds in his beard, he told me that they had been there, but they’d all grown up now and flown the nest ‘like little birds do, like we all do in the end’.

It’s not so surprising, when I come to think about it now, that you were such a compelling reader, such a magical storyteller. Until you married for the second time you had been an actress like your own mother, like your brother, like our first father too. It was in your blood to love words, to love stories (I think maybe it’s in mine too – and Piet’s, he’s spent all his working life in theatre or television). You could make your voice sing and dance. You could be an elephant or a cat or even a crocodile – no trouble at all. You could do ghosts and pirates – Marley’s ghost in A Christmas Carol, Captain Hook in Peter Pan. You simply became them. So Piet and I lived every story, believed every character. You brought them to life for us. Our imaginations soared on the wings of your words. And that was a fine and wonderful thing – mostly.

But the trouble was that with one poem in particular you were far too good, far too frightening. You scared me half to death every time you recited it. I don’t think you realised it at first because I was adept at toughing it out. I’d feign terror, clap my hands dramatically over my ears while you were reading, make a whole big scene of being terrified, to cover up the fact that I was.