По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

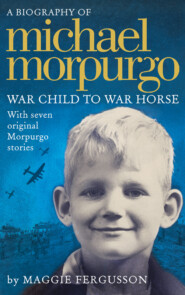

Michael Morpurgo: War Child to War Horse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The fire officer was talking to Aunty B and Aunty J. ‘It looks like some idiot, some old tramp maybe, has gone in that bomb site and started a fire to keep himself warm.’ He shook his head. ‘Though what an old witches’ cauldron is doing down there, God only knows. We’ve managed to confine the fire to your basement, but it’s totally burned out in there, gutted. There’s only smoke damage in the house itself, though we’ve had to use a lot of water to get the fire under control, so it’s a bit of a mess, I’m afraid. Still, we must be thankful for small mercies’ – he ruffled my hair – ‘these little mercies I’m talking about. You got them to safety and that’s all that really matters, isn’t it, when all’s said and done?’

The three of us didn’t dare look at one another, or at anyone else, in case the guilt showed in our eyes. We went to sleep in Belinda’s house that night, and stayed there for a week or more while Aunty B and Aunty J got the house cleared up for your return. I remember them breaking the news of the fire to you on the doorstep and how you tried to comfort them as, tearfully, they relived every moment of it. You kept hugging them, telling them how wonderful they had been to save Pieter and me, and in the end that seemed to make them feel better.

But Piet and I didn’t feel better. We haven’t felt better about it all our lives, and to be honest, telling you about it now hasn’t helped as much as I hoped it might. Hiding this terrible secret from you, for as long as we have, has been at least as bad as the guilt we felt on the night it happened. It seems confession is not enough.

The trouble is there’s another secret we never told you. It’s not as bad as the burning of your love-letters and your wedding photo, or setting fire to the house, but it was a secret we couldn’t tell, because if we had told it, all the others would have come out too.

The Christmas after the fire Gran came to stay, if you remember. She gave you a present. You opened it and showed it to us, probably with tears in your eyes – you always had tears in your eyes when you spoke about him.

‘Look, boys, what Gran has given us,’ you said. ‘It’s a photo of your uncle Pieter in his RAF uniform. Doesn’t he look fine?’

You passed it to Piet and me. It was the first time we’d ever seen a photo of him. Looking up at us, out of the silver frame, without any question, was the face of the stranger we had met in the bomb site that foggy day. We knew it at once.

That is the secret I feel saddest about now, because it might have been a great comfort to you if we’d had the courage to tell you.

Some time after you died, far from any of us, out in America, in Washington, I happened to find myself near St Eval in Cornwall at the RAF station where I’d been told Uncle Pieter’s plane had crashed in 1941. I stood there on what was left of the runway and told him at last that I knew it had been him who came to see us in the bomb site all those years before. He didn’t speak, I didn’t see him – but he was there, I am sure of it. And you were there too, Mum, I’m sure of that as well. It was a spring day. The hawthorns were white in the hedges, the daffodils blowing in the wind, and the blackbirds calling to one another over the fields.

2 Spotless Officer Number One (#uacfd6f7b-2c31-531a-a2d7-3dcd63ddbf77)

Saturday 19 December 2009; the Dragon School, Oxford. The playing fields are white with frost, but the Lynam Hall is a hive of warmth and colour as parents and children cram in to hear Michael Morpurgo open the Dragon Christmas Sale. As he strides on to the stage, draped in a long, multicoloured, Dr Who scarf, he is running on empty. The last week alone has taken him to two bookshop signings in London, and stage productions of The Best Christmas Present in the World in Bristol and On Angel Wings in Winchester. Exhaustion shows when it comes to taking questions. ‘By the way,’ he tells a little girl in a lime-green top, after answering her question about where his stories come from, ‘the colour of your shirt is appalling.’ She blushes to the roots of her hair.

In talking to groups of children Michael adopts what the illustrator Emma Chichester Clark calls his ‘angry headmaster mode’, projecting a persona that is knockabout, bumptious and ‘seemingly’, he admits, ‘rather over-confident’. But the man you discover when you spend time with Michael at his home in Devon is quite different: thoughtful, unsure of his gifts, frightened of the blank page, and prone to melancholy. This ‘schizophrenia’ (his word) bothers him. ‘I’m comfortable in both parts,’ he confesses, ‘but I’m uncomfortable with the fact that I seem to need two parts. And I am certainly uncomfortable with the effect that this has on the people I love.’ He is referring to his wife and children, but they come later in the story, years after the seeds of his ‘schizophrenia’ were sown at The Abbey, near East Grinstead in Sussex.

In the second half of the last century, Sussex and Kent were honeycombed with prep schools. Middle-class boys were squirrelled away in them in such large numbers that, arriving at Victoria Station at the end of the holidays, they were obliged to join a scrum of children squeezing around a blackboard to get directions to the railway carriages specially reserved for the Abbey, Ashdown House, Brambletye, Fonthill Lodge, Hazelwood, Hillsbrow …

Many of these schools are still going strong, but the Abbey long since fell victim to financial mismanagement, closed its doors to pupils, and was sold to a property developer and converted into flats. Yet from the outside the house looks exactly the same today as the one to which Michael returns often in his dreams: an ugly, late-Victorian, mock-baronial pile; a jumble of turrets and mullioned windows and brick excrescences. A weather-vane pokes up, slightly cockeyed, amidst a coppice of top-heavy chimneys, and there is a bleak stone inscription – PERSEVERANTIA – above an ivy-clad front door. The buildings around the main house are now suburban dwellings, but their names hint at the past – one is called ‘Gymnasium’, another ‘The Old Laundry’ – and walking through the overgrown gardens that surround them is like stepping into the pages of Michael’s books. There is the stream, swelled in Michael’s imagination to a river, across which the ‘toffs’ and the ‘oiks’ fought their battles in The War of Jenkins’ Ear; and the woods in which a blond boy called Christopher made a chapel with a log altar and a straw floor, and persuaded his contemporaries that he was Jesus come again. And at the bottom of the school park is the fence over which Michael – later Bertie in The Butterfly Lion – climbed, overcome with homesickness, in a bid to run away from school.

Visiting the Abbey on a drizzly afternoon in late winter, one feels that the dripping rhododendrons are haunted by the homesickness which Michael suffered from the moment he arrived. It was worst at night. There was something about the moment that Matron, strict but kind, called ‘Lights Out!’ that made him yearn for his mother. And though darkness was a relief, allowing the tears to roll down his cheeks unseen, sleep did not come easily. Beyond the dormitory window was a clock tower that chimed the quarters, ‘slicing up the night’; and the night was dominated by anxiety about the following day.

In a tatty copy of the Abbey school magazine from 1957, after a ‘hail and farewell’ section in which the staff seem to have been drawn straight from a pack of Happy Families – goodbye Mr Kane, head of senior Classics; welcome Mr Bent, English master, and Miss Kitkat, junior matron – there is the précis of a speech given to the boys by a visiting headmaster at their summer prize-giving. Those who have won cups must win more next year, he insists. Those who have not must work harder. And those at the bottom of their classes should resolve to be ‘at least halfway up’ by the time he visits again.

Academic success mattered. Measured in ‘pluses’ and ‘minuses’, ‘unders’ and ‘overs’, the performance of every boy was calculated weekly and read out to the whole school on a Sunday evening. Those who did well became ‘Centurions’. Those who did badly were punished. At worst, this meant a journey up the red-carpeted stairway, ‘the Bloody Steps’, to the study of fat-fingered Mr Crump, one of the triumvirate of headmasters, for a caning. Canings took place amidst a collection of African tribal artefacts and hunting trophies left by the Abbey’s previous owner, gambler and mining millionaire Sir Abe Bailey: ‘Swish. Then “Ow, sir!” You had to shake Crump’s hand when it was finished.’

Michael had his fair share of punishment. Pigeonholed from the start as not especially bright – ‘Very much below the standard of the form,’ his Maths master noted at the end of his first term – he remained, throughout his time at the Abbey, somewhere around the middle to bottom of his year. He was not helped by his stutter, which grew steadily worse, tripping him up on his ‘c’s and ‘f’s and ‘w’s. If there was a poem to learn, or a string of history dates, he would lie in the early hours of the morning contriving ways of sliding over these troublesome consonants. This did not always work, and when it failed he was teased. Then he would blush, and then he would be teased again: ‘You’re going red, Morpurgo …’ Anxiety brought on chronic eczema – cracking, weeping knee and arm joints, which Matron daubed with ointment at bedtime, before feeding Michael one tablespoonful of Radio Malt, to build him up.

He might have cut a pathetic figure had not the ‘other’ Michael Morpurgo, the waggish, confident doppelgänger who has accompanied him through life, come to his rescue. Perhaps it was his theatrical genes that enabled him to drop a visor of confidence over his vulnerability; or perhaps it was Jack Morpurgo. Jack’s treatment of Pieter, who was even less academic than Michael, bordered on cruelty. Observing it, Michael had learned early that the only way to rub along with his stepfather was to devise ways to win praise, even if this involved deceit.

Edna Macleod, who, with her husband, Ian, spent so much time with Kippe and Jack that the joint families became known as the ‘Macpurgos’, remembers one Christmas morning on which Pieter got up early to make Edna and Ian breakfast in bed. Just as he was about to carry the tray into their room, Michael lifted it from his hands, walked through and presented it to Edna – ‘getting all the kudos’. Michael was ‘a monkey’, Edna says, but also ‘irresistible’. At home, family and friends were enchanted by his ‘intelligence and humour and charm’.

Very quickly, the same was true at school. Once it was clear that he was not going to shine academically, he found other areas in which he could come out on top. In the Abbey magazine the achievements of ‘Morpurgo ii’ are lauded on almost every page. He is Chapel Warden and Chief Chorister. He is the only boy wheeled out to play a violin solo, ‘Highland Heather’, in the Christmas carol concert. He is in the tennis team, and he is Captain of Cricket. He carries off the cups for Batting, Choir and Personal Merit. Above all, he is a hero on the rugby pitch. Reports of matches against neighbouring schools are peppered with descriptions of his triumphs: ‘From a quick heel, Morpurgo scored a good try’; ‘Morpurgo’s covering and tackling were excellent’; ‘Morpurgo found his swerve would not work on the slippery surface’ but ‘did some good defensive kicking’ instead. Bookish he might not be, but the magazine editor is confident that ‘a great Rugger future’ lies before him.

First XV at The Abbey, winter 1954. Mr Beagley stands centre back, Michael sits cross-legged, front left.

His sporting triumphs brought multiple benefits. They had an anaesthetising effect on Jack, numbing him to Michael’s mediocre academic reports: ‘Far too inclined to flounder about in a sea of ink and inaccuracies’ (Maths); ‘His mapwork is untidy’ (Geography); ‘I do not understand him’ (French); ‘An exasperating boy’ (English); ‘Rather excitable and harum-scarum’ (Headmaster). And they impressed the other boys, among whom Michael both relished and mistrusted his reputation as a ‘clubbable and charismatic’ hero. But, perhaps most importantly of all, they were rewarded with treats – rare, delicious opportunities to break the bounds of the Abbey and taste the wider world.

Like many of the other Abbey parents, Kippe and Jack barely ever came to visit the boys, so that even on ‘Leave-out’ Sundays the only hope of escape was to angle for an invitation from Humphrey and Peregrine Swann to join them, with their parents, for lunch at the Letherby and Christopher Hotel in East Grinstead. But success in sports, and in the choir, earned Michael visits to the cinema, and even, on one never-to-be-forgotten occasion, a trip to see Così fan tutte at Glyndebourne. Mr Gladstone, the most sympathetic of the three headmasters, drove the boys in his black Humber convertible, he and his wife, Kitty, in the front, Michael and two others in the back. They purred through the summer dusk, the Downs stretching before them like a Ravilious painting. The memory remains magical.

What did they wear for that outing? Such things mattered to Michael. His two most treasured possessions at the Abbey were the red ribbon he was awarded as Chief Chorister, and the green velvet cap that marked him out as Captain of Rugby. Like the children’s television character Mr Benn, he felt most at home in a costume: ‘I liked playing a part,’ he says. ‘It meant I could forget about myself.’ And this was a relief, because he was unsure of his real identity. On the rugby pitch, while the other boys cheered his courage, he felt afraid and oddly detached. ‘When I went in for a tackle, I did it closing my eyes because I was so scared,’ he says. ‘Part of me was there, in the scrum; but part of me was standing at the side of the pitch, watching.’ This sense of involved detachment persists. As he talks at the Dragon School on that cold winter morning, his storyteller’s costume – red trousers, black beret, stripy scarf – gives him the identity he needs to communicate with children, while at the same time enabling him to remain essentially hidden.

So how many people know Michael Morpurgo really well? ‘Very few,’ he believes. ‘My brother, Pieter, and my half-brother, Mark, they know me.’ But when I visit Mark, born to Kippe and Jack in 1948, at his home in the Scottish Highlands, he suggests otherwise. ‘I wonder whether you will be able to get to the bottom of Michael,’ he muses. ‘I love him, but he’s an enigma to me.’ Peter Campbell, possibly Michael’s closest school friend, agrees: ‘You’ll never really know Michael,’ he says, ‘and he’ll never really know himself.’

Homesickness afflicted Michael throughout his years at the Abbey, and beyond. It began to take a hold about a fortnight before the end of the holidays, when his stepaunts, Bess and Julie, fetched their sewing baskets and got busy with nametapes. Soon afterwards the brown leather trunk was hauled out, packed, and delivered to the station to travel in advance – ‘and you knew from that moment that you were on a wave that would carry you, like it or not, back to school’. Then came the last supper (always shepherd’s pie), the last night at home, and the dreaded journey.

On Victoria Station, in those days, there was a small newsreel cinema, to which Kippe would take the boys for a final treat before surrendering them to the barrel-chested rugby master, Mr Beagley. This was a boon. The cinema’s dark interior served as a kind of decompression chamber where, as Bugs Bunny or Mickey Mouse flickered on the screen, Michael could allow his ‘home’ self to slip away, and arm himself for school.

After that, it was best if Kippe left quickly. She was the focus for Michael’s homesickness, but she was also an embarrassment to him. When they married, Kippe and Jack had decided that, as Pieter and Michael could not be expected to call Jack ‘Daddy’, they should cease to call Kippe ‘Mummy’. They should address them both simply as ‘Kippe’ and ‘Jack’ – and any further children born to them should do the same. The boys at the Abbey, quick to spot chinks in one another’s emotional armour, homed in on this oddity. ‘Jack is not your real father,’ they taunted, ‘and Kippe is a weird name.’ So it was a relief, really, when she turned to walk away, wrapped in her fragile sadness, smelling of face-powder. Michael could then settle into the corner of a railway carriage. To prevent himself from crying he concentrated on following raindrops down the thick windows with his finger, as the train wound out through south London, which was still pockmarked with bomb damage.

Yet, as the terms passed, Michael became aware that his homesickness was more habitual than real, and that there were things about school that he was growing not just to tolerate but to love.

The Abbey is set on high ground, and to the south its gardens tumble gently downwards, allowing wide views over Ashdown Forest. Between the formal garden and the forest were forty acres of school grounds, and on summer evenings the boys were left to ‘play out’ here, unsupervised, until the light failed. The memory of these evenings remains vivid and glorious – ‘I was at that age when one is wide open to everything, antennae out.’ These were hours of camps and camaraderie, of whittling arrows with sheath knives and exchanging secrets.

Winter evenings had a different charm. One of the headmasters, Mr Frith, regularly invited a group of boys to come to his study after supper and sit by the fire in their pyjamas. He served orange squash and Garibaldi biscuits, and read aloud from the novels of Dornford Yates: mild, sex-free thrillers, which had enjoyed a vogue between the wars, and in which the narrator-hero, Richard Chandos, drove about the Continent in a ‘Rolls’ tackling crime and hunting treasure. Michael loved these evenings – the warmth, the involvement in a story, the feeling of belonging. He slept well after them.

He was not, himself, a great reader – or at least not the kind that Jack Morpurgo would have wished him to be. The leather-bound copies of Dickens that Jack periodically put Michael’s way were anathema to him, and to this day he has to overcome a psychological block before tackling large books, and cannot happily read for more than an hour at a stretch. But he was saved from Jack’s contempt by a series called Great Illustrated Classics – easy-to-read, large-print abridgements which, borrowed from other boys and studied in secret, enabled him to pretend that he had read not only much of Dickens, but also of Homer, Dostoevsky and Sir Walter Scott. Privately, meantime, he was developing his own taste for really good yarns, in which pictures relieved his fear of text, so that the text could create pictures in his mind. He devoured the novels of G. A. Henty, of Kipling and, above all, of Robert Louis Stevenson: ‘I was Jim Hawkins,’ he says, remembering his first reading of Treasure Island. ‘I was in that barrel of apples on the deck of the Hispaniola; I overheard the plots of mutiny.’

He was gripped, too, by the stories of real men. On the ground floor of the Abbey was a library, a dark, musty room, whose deep leather armchairs gave the atmosphere of a gentleman’s club, and whose glass-fronted bookcases reached to the ceiling. The shelves were filled, for the most part, with books that had belonged to Sir Abe Bailey; and among these were bound copies of the Illustrated London News, stretching back to the mid-nineteenth century. Michael spent hours of his free time poring over black-and-white pencil sketches of soldiers fighting and dying in the Crimea and in the Balkan Wars.

History lessons fed his appetite for heroes. He remembers marvelling at the courage of Joan of Arc, steadfast at her stake as the flames began to lick around her; at the cunning of William the Conqueror, instructing his archers to fire into the air so that Harold’s men would look up and get arrows in their eyes; at the valour of Simon de Montfort as he fell to his death at the Battle of Evesham. But one man preoccupied him more than any other, and that was Jesus.

The pupils at the Abbey filed into the school chapel every morning, and twice on a Sunday. But Michael, privately, went much more often. Apart from the ‘bog’, the chapel was the one place he could escape the other boys, and he liked being alone there with his thoughts, sitting before the altar where there was always a red lamp flickering. Though his faith was uncertain – ‘I wanted to believe; I still do’ – he felt drawn to the life of Jesus, told in stained glass. He longed to meet the man, yet at the same time felt sure that, were they to meet, Jesus would dislike him – ‘because he was more perceptive than other people, and would see straight through me’. The mask he had developed to protect his more private, sensitive self from the sink-or-swim perils of prep school was already a source of confusion and guilt.

At home, Michael could allow his mask to slip, and his elation at the start of each school holidays was greater than any he has since experienced. Kippe and Jack had moved, in 1950, to a small village, Bradwell-juxta-Mare, on the Essex coast. With financial help from Bess and Julie they bought a large, haunted, sixteenth-century house, set in several acres of garden. In the post-war years, as domestic staff became for many a thing of the past, houses like New Hall had dropped in value. Buyers were struck less by the beauty of their architecture than by the number of windows that needed cleaning, floors sweeping, stairs running up and down. But Jack Morpurgo, socially ambitious and domestically impractical, had no such misgivings. What he saw in New Hall was a house that confirmed his transformation from East End working-class boy to English country squire.

Michael loved New Hall for other reasons. Its down-at-heel, rambling cosiness gave him a sense of belonging, and all the houses he has lived in since have been in some way attempts to recapture this. He and Pieter slept in adjoining attic bedrooms, with low sloping roofs, reached by a narrow staircase which the rest of the household rarely climbed. This was their private world, in which they made candles on a paraffin stove, read Tintin and Asterix and novels by Enid Blyton, all outlawed by Jack, and hoisted themselves out of the windows at night to sit in the leaded gully running between the roof and the house façade. The darkness was filled with the hooting of owls, the calls of wildfowl, and the mournful arhythmic clanging of boat riggings a couple of miles away, beyond the salt marshes, in the Blackwater Estuary.

The garden, too, was a boy’s paradise, with a smooth front lawn for cricket and slip catching, and beamed stables with a sagging roof in which Pieter and Michael built a giant racetrack for their cars and played ping-pong on rainy days. To the back of the house the garden had been allowed to run wild. Dog roses climbed over two old Nissen huts that had been used as a mess by RAF fighter squadrons flying out of Bradwell airfield during the war. There was an overgrown orchard with apple, pear, plum and damson trees, and a mulberry bush from which, in the summer holidays, Pieter and Michael harvested the purple, staining fruit in boiler suits.

Pieter, Mark and Michael outside New Hall.

Around the garden ran a high wall, up to which the sea would occasionally flood. The wall was a statement in mottled brick that New Hall was the big house; that its inhabitants lived somehow apart from the rest of the village. It taught Michael his first lessons about class division, because local boys liked to scale it, lean over the top, and jeer at the ‘posh kids’ on the other side.

When the Morpurgo brothers came out of the front gates these boys sometimes formed roadblocks, or kicked their bicycles, or threw stones. None of this deterred Pieter and Michael. If they loved the world within the garden wall, they loved what lay beyond it also. Bradwell-juxta-Mare was the sort of quintessentially English village that might have sprung from the pages of an Agatha Christie novel. Opposite New Hall was the home of retired Major Turpin; a little further along the road the three Miss Stubbings, spinster sisters, shared a cottage with wisteria around the door. And in the only other big house lived the Labour MP Tom Driberg. He struck Michael as ‘fat and foul’, though he knew nothing of Driberg’s rampant homosexuality, which was still in those days a criminal offence.

Between the village and the sea lay a stretch of marshland that entered deeply into Michael’s imagination – the marshland Paul Gallico captures in the opening pages of The Snow Goose: ‘one of the last wild places of England, a low, far-reaching expanse of grass and reeds and half-submerged meadowlands ending in the great saltings and mud flats and tidal pools near the restless sea’.

It is a rich landscape for a storyteller, sunk so deep in time that distinctions between the ordinary and the fabulous begin to blur. Towards the end of the third century the Romans established a fort, Othona, on the coast by Bradwell. Four hundred years on, at the invitation of the Christian King Sigbert, a Lindisfarne monk, Cedd, arrived in a small boat. Using blocks of Kentish ragstone from Othona, he built a chapel in the sea wall. St Peter-on-the-Wall remains to this day, standing square against the huge Essex sky like a symbol of simplicity, perseverance and strength. Michael loved to sit alone by St Peter’s, with the past for company. ‘The Romans had been here, and the Saxons, and the Normans. And now me.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: