По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

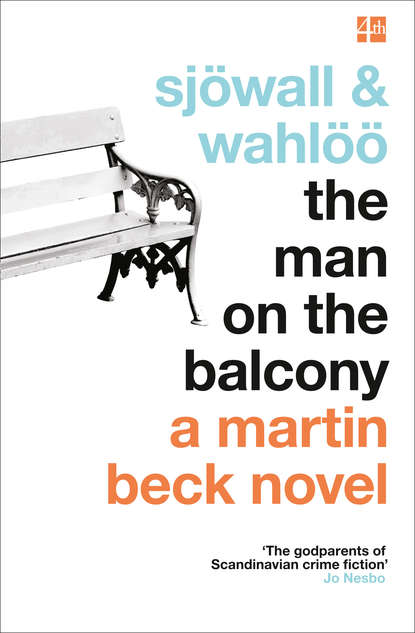

The Man on the Balcony

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Do you mind if we sit down?’ Kollberg asked, and sat in one of the armchairs.

The woman remained standing and said:

‘What has happened? Have you found her?’

Kollberg saw the dread and the panic in her eyes and tried to keep quite calm.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Please sit down, Mrs Carlsson. Where is your husband?’

She sat in the armchair opposite Kollberg.

‘I have no husband. We're divorced. Where's Eva? What has happened?’

‘Mrs Carlsson, I'm terribly sorry to tell you this. Your daughter is dead.’

The woman stared at him.

‘No,’ she said. ‘No.’

Kollberg got up and went over to her.

‘Have you no one who can be with you? Your parents?’

The woman shook her head.

‘It's not true,’ she said.

Kollberg put his hand on her shoulder.

‘I'm terribly sorry, Mrs Carlsson,’ he said lamely.

‘But how? We were going to the country…’

‘We're not sure yet,’ Kollberg replied. ‘We think that she … that she's been the victim of…’

‘Killed? Murdered?’

Kollberg nodded.

The woman shut her eyes and sat stiff and still. Then she opened her eyes and shook her head.

‘Not Eva,’ she said. ‘It's not Eva. You haven't … you've made a mistake.’

‘No,’ Kollberg said. ‘I can't tell you how sorry I am, Mrs Carlsson. Isn't there anyone I can call? Someone I can ask to come here? Your parents or someone?’

‘No, no, not them. I don't want anyone here.’

‘Your ex-husband?’

‘He's living in Malmö, I think.’

Her face was ashen and her eyes were hollow. Kollberg saw that she had not yet grasped what had happened, that she had put up a mental barrier which would not allow the truth past it. He had seen the same reaction before and knew that when she could no longer resist, she would collapse.

‘Who is your doctor, Mrs Carlsson?’ Kollberg asked.

‘Doctor Ström. We were there on Wednesday. Eva had had a tummy ache for several days and as we were going to the country I thought I'd better…’

She broke off and looked at the doorway into the other room.

‘Eva's never sick as a rule. And she soon got over this tummy ache. The doctor thought it was a touch of gastric flu.’

She sat silent for a moment. Then she said, so softly that Kollberg could hardly catch the words:

‘She's all right again now.’

Kollberg looked at her, feeling desperate and idiotic. He did not know what to say or do. She was still sitting with her face turned towards the open door into her daughter's room. He was trying frantically to think of something to say when she suddenly got up and called her daughter's name in a loud, shrill voice. Then she ran into the other room. Kollberg followed her.

The room was bright and nicely furnished. In one corner stood a red-painted box full of toys and at the foot of the narrow bed was an old-fashioned doll's house. A pile of schoolbooks lay on the desk.

The woman was sitting on the edge of the bed, her elbows propped on her knees and face buried in her hands. She rocked to and fro and Kollberg could not hear whether she was crying or not.

He looked at her for a moment, then went out into the hall where he had seen the telephone. An address book lay beside it and in it, sure enough, he found Doctor Ström's number.

The doctor listened while Kollberg explained the situation and promised to come within five minutes.

Kollberg went back to the woman, who was sitting as he had left her. She was making no sound. He sat down beside her and waited. At first he wondered whether he dared touch her, but after a while he put his arm cautiously around her shoulders. She seemed unaware of his presence.

They sat like this until the silence was broken by the doctor's ring at the door.

8 (#ulink_a8a950a0-da19-550d-bc24-5c6455da7496)

Kollberg was sweating as he walked back through Vanadis Park. The cause was neither the steep incline, the humid heat after the rain, nor his tendency to corpulence. At any rate not entirely.

Like most of those who were to deal with this case, he was jaded before the investigation started. He thought of the repulsiveness of the crime itself and he thought of the people who had been so hard hit by its blind meaninglessness. He had been through all this before, how many times he couldn't even say offhand, and he knew exactly how horrible it could turn out to be. And how difficult.

He thought too of the swift gangsterization of this society, which in the last resort must be a product of himself and of the other people who lived in it and had a share in its creation. He thought of the rapid technical expansion that the police force had undergone merely during the last year; despite this, crime always seemed to be one step ahead. He thought of the new investigation methods and the computers, which could mean that this particular criminal might be caught within a few hours, and also what little consolation these excellent technical inventions had to offer the woman he had just left, for example. Or himself. Or the set-faced men who had now gathered around the little body in the bushes between the rocks and the red fence.

He had only seen the body for a few moments, and at a distance, and he didn't want to see it again if he could help it. This he knew to be an impossibility. The mental image of the child in the blue skirt and striped T-shirt was etched into his mind and would always remain there, together with all the others he could never get rid of. He thought of the wooden-soled sandals on the slope and of his own child, as yet unborn; of how this child would look in nine years’ time; of the horror and disgust that this crime would arouse, and what the front pages of the evening papers would look like.

The entire area around the gloomy, fortress-like water tower was roped off now, as well as the steep slope behind it, right down to the steps leading to Ingemarsgatan. He walked past the cars, stopped at the cordon and looked out over the empty playground with its sandpits and swings.

The knowledge that all this had happened before and was certain to happen again was a crushing burden. Since the last time they had got computers and more men and more cars. Since the last time the lighting in the parks had been improved and most of the bushes had been cleared away. Next time there would be still more cars and computers and even less shrubbery. Kollberg wiped his brow at the thought and the handkerchief was wet through.

The journalists and photographers were already there, but fortunately only a few of the inquisitive had as yet found their way here. The journalists and photographers, oddly enough, had become better with the years, partly thanks to the police. The inquisitive would never be any better.

The area around the water tower was strangely quiet, despite all the people. From afar, perhaps from the swimming pool or the playground at Sveavägen, cheerful shouts could be heard and children laughing.

Kollberg remained standing by the cordon. He said nothing, nor did anyone speak to him.