По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

Gone with the Wind. Volume 2 / Унесенные ветром. Том 2

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“The truth at last. Talking love and thinking money. How truly feminine! Do you need the money badly?”

“Oh, ye- Well, not so terribly but I could use it.”

“Three hundred dollars. That's a vast amount of money. What do you want it for?”

“To pay taxes on Tara.”

“So you want to borrow some money. Well, since you're so businesslike, I'll be businesslike too. What collateral will you give me?”

“What what?”

“Collateral. Security on my investment. Of course, I don't want to lose all that money.” His voice was deceptively smooth, almost silky, but she did not notice. Maybe everything would turn out nicely after all.

“My earrings.”

“I'm not interested in earrings.”

“I'll give you a mortgage on Tara.”

“Now just what would I do with a farm?”

“Well, you could-you could-it's a good plantation. And you wouldn't lose. I'd pay you back out of next year's cotton.”

“I'm not so sure.” He tilted back in his chair and stuck his hands in his pockets. “Cotton prices are dropping. Times are so hard and money's so tight.”

“Oh, Rhett, you are teasing me! You know you have millions!”

There was a warm dancing malice in his eyes as he surveyed her.

“So everything is going nicely and you don't need the money very badly. Well, I'm glad to hear that. I like to know that all is well with old friends.”

“Oh, Rhett, for God's sake…” she began desperately, her courage and control breaking.

“Do lower your voice. You don't want the Yankees to hear you, I hope. Did anyone ever tell you you had eyes like a cat-a cat in the dark?”

“Rhett, don't! I'll tell you everything. I do need the money so badly. I–I lied about everything being all right. Everything's as wrong as it could be. Father is-is-he's not himself. He's been queer ever since Mother died and he can't help me any. He's just like a child. And we haven't a single field hand to work the cotton and there's so many to feed, thirteen of us. And the taxes-they are so high. Rhett, I'll tell you everything. For over a year we've been just this side of starvation. Oh, you don't know! You can't know! We've never had enough to eat and it's terrible to wake up hungry and go to sleep hungry. And we haven't any warm clothes and the children are always cold and sick and-”

“Where did you get the pretty dress?”

“It's made out of Mother's curtains,” she answered, too desperate to lie about this shame. “I could stand being hungry and cold but now-now the Carpetbaggers have raised our taxes. And the money's got to be paid right away. And I haven't any money except one five-dollar gold piece. I've got to have money for the taxes! Don't you see? If I don't pay them, I'll-we'll lose Tara and we just can't lose it! I can't let it go!”

“Why didn't you tell me all this at first instead of preying on my susceptible heart-always weak where pretty ladies are concerned? No, Scarlett, don't cry. You've tried every trick except that one and I don't think I could stand it. My feelings are already lacerated with disappointment at discovering it was my money and not my charming self you wanted.”

She remembered that he frequently told bald truths about himself when he spoke mockingly-mocking himself as well as others, and she hastily looked up at him. Were his feelings really hurt? Did he really care about her? Had he been on the verge of a proposal when he saw her palms? Or had he only been leading up to another such odious proposal as he had made twice before? If he really cared about her, perhaps she could smooth him down. But his black eyes raked her in no lover-like way and he was laughing softly.

“I don't like your collateral. I'm no planter. What else have you to offer?”

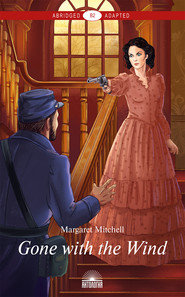

Well, she had come to it at last. Now for it! She drew a deep breath and met his eyes squarely, all coquetry and airs gone as her spirit rushed out to grapple that which she feared most.

“I–I have myself.”

“Yes?”

Her jaw line tightened to squareness and her eyes went emerald.

“You remember that night on Aunt Pitty's porch, during the siege? You said-you said then that you wanted me.”

He leaned back carelessly in his chair and looked into her tense face and his own dark face was inscrutable. Something flickered behind his eyes but he said nothing.

“You said-you said you'd never wanted a woman as much as you wanted me. If you still want me, you can have me. Rhett, I'll do anything you say but, for God's sake, write me a draft for the money! My word's good. I swear it. I won't go back on it. I'll put it in writing if you like.”

He looked at her oddly, still inscrutable and as she hurried on she could not tell if he were amused or repelled. If he would only say something, anything! She felt her cheeks getting hot.

“I have got to have the money soon, Rhett. They'll turn us out in the road and that damned overseer of Father's will own the place and-”

“Just a minute. What makes you think I still want you? What makes you think you are worth three hundred dollars? Most women don't come that high.”

She blushed to her hair line and her humiliation was complete.

“Why are you doing this? Why not let the farm go and live at Miss Pittypat's. You own half that house.”

“Name of God!” she cried. “Are you a fool? I can't let Tara go. It's home. I won't let it go. Not while I've got breath left in me!”

“The Irish,” said he, lowering his chair back to level and removing his hands from his pockets, “are the damnedest race. They put so much emphasis on so many wrong things. Land, for instance. And every bit of earth is just like every other bit. Now, let me get this straight, Scarlett. You are coming to me with a business proposition. I'll give you three hundred dollars and you'll become my mistress.”

“Yes.”

Now that the repulsive word had been said, she felt somehow easier and hope awoke in her again. He had said “I'll give you.” There was a diabolic gleam in his eyes as if something amused him greatly.

“And yet, when I had the effrontery to make you this same proposition, you turned me out of the house. And also you called me a number of very hard names and mentioned in passing that you didn't want a 'passel of brats.' No, my dear, I'm not rubbing it in. I'm only wondering at the peculiarities of your mind. You wouldn't do it for your own pleasure but you will to keep the wolf away from the door. It proves my point that all virtue is merely a matter of prices.”

“Oh, Rhett, how you run on! If you want to insult me, go on and do it but give me the money.”

She was breathing easier now. Being what he was, Rhett would naturally want to torment and insult her as much as possible to pay her back for past slights and for her recent attempted trickery. Well, she could stand it. She could stand anything. Tara was worth it all. For a brief moment it was mid-summer and the afternoon skies were blue and she lay drowsily in the thick clover of Tara's lawn, looking up at the billowing cloud castles, the fragrance of white blossoms in her nose and the pleasant busy humming of bees in her ears. Afternoon and hush and the far-off sound of the wagons coming in from the spiraling red fields. Worth it all, worth more.

Her head went up.

“Are you going to give me the money?”

He looked as if he were enjoying himself and when he spoke there was suave brutality in his voice.

“No, I'm not,” he said.

For a moment her mind could not adjust itself to his words.

“I couldn't give it to you, even if I wanted to. I haven't a cent on me. Not a dollar in Atlanta. I have some money, yes, but not here. And I'm not saying where it is or how much. But if I tried to draw a draft on it, the Yankees would be on me like a duck on a June bug and then neither of us would get it. What do you think of that?”

Her face went an ugly green, freckles suddenly standing out across her nose and her contorted mouth was like Gerald's in a killing rage. She sprang to her feet with an incoherent cry which made the hum of voices in the next room cease suddenly. Swift as a panther, Rhett was beside her, his heavy hand across her mouth, his arm tight about her waist. She struggled against him madly, trying to bite his hand, to kick his legs, to scream her rage, despair, hate, her agony of broken pride. She bent and twisted every way against the iron of his arm, her heart near bursting, her tight stays cutting off her breath. He held her so tightly, so roughly that it hurt and the hand over her mouth pinched into her jaws cruelly. His face was white under its tan, his eyes hard and anxious as he lifted her completely off her feet, swung her up against his chest and sat down in the chair, holding her writhing in his lap.

“Oh, ye- Well, not so terribly but I could use it.”

“Three hundred dollars. That's a vast amount of money. What do you want it for?”

“To pay taxes on Tara.”

“So you want to borrow some money. Well, since you're so businesslike, I'll be businesslike too. What collateral will you give me?”

“What what?”

“Collateral. Security on my investment. Of course, I don't want to lose all that money.” His voice was deceptively smooth, almost silky, but she did not notice. Maybe everything would turn out nicely after all.

“My earrings.”

“I'm not interested in earrings.”

“I'll give you a mortgage on Tara.”

“Now just what would I do with a farm?”

“Well, you could-you could-it's a good plantation. And you wouldn't lose. I'd pay you back out of next year's cotton.”

“I'm not so sure.” He tilted back in his chair and stuck his hands in his pockets. “Cotton prices are dropping. Times are so hard and money's so tight.”

“Oh, Rhett, you are teasing me! You know you have millions!”

There was a warm dancing malice in his eyes as he surveyed her.

“So everything is going nicely and you don't need the money very badly. Well, I'm glad to hear that. I like to know that all is well with old friends.”

“Oh, Rhett, for God's sake…” she began desperately, her courage and control breaking.

“Do lower your voice. You don't want the Yankees to hear you, I hope. Did anyone ever tell you you had eyes like a cat-a cat in the dark?”

“Rhett, don't! I'll tell you everything. I do need the money so badly. I–I lied about everything being all right. Everything's as wrong as it could be. Father is-is-he's not himself. He's been queer ever since Mother died and he can't help me any. He's just like a child. And we haven't a single field hand to work the cotton and there's so many to feed, thirteen of us. And the taxes-they are so high. Rhett, I'll tell you everything. For over a year we've been just this side of starvation. Oh, you don't know! You can't know! We've never had enough to eat and it's terrible to wake up hungry and go to sleep hungry. And we haven't any warm clothes and the children are always cold and sick and-”

“Where did you get the pretty dress?”

“It's made out of Mother's curtains,” she answered, too desperate to lie about this shame. “I could stand being hungry and cold but now-now the Carpetbaggers have raised our taxes. And the money's got to be paid right away. And I haven't any money except one five-dollar gold piece. I've got to have money for the taxes! Don't you see? If I don't pay them, I'll-we'll lose Tara and we just can't lose it! I can't let it go!”

“Why didn't you tell me all this at first instead of preying on my susceptible heart-always weak where pretty ladies are concerned? No, Scarlett, don't cry. You've tried every trick except that one and I don't think I could stand it. My feelings are already lacerated with disappointment at discovering it was my money and not my charming self you wanted.”

She remembered that he frequently told bald truths about himself when he spoke mockingly-mocking himself as well as others, and she hastily looked up at him. Were his feelings really hurt? Did he really care about her? Had he been on the verge of a proposal when he saw her palms? Or had he only been leading up to another such odious proposal as he had made twice before? If he really cared about her, perhaps she could smooth him down. But his black eyes raked her in no lover-like way and he was laughing softly.

“I don't like your collateral. I'm no planter. What else have you to offer?”

Well, she had come to it at last. Now for it! She drew a deep breath and met his eyes squarely, all coquetry and airs gone as her spirit rushed out to grapple that which she feared most.

“I–I have myself.”

“Yes?”

Her jaw line tightened to squareness and her eyes went emerald.

“You remember that night on Aunt Pitty's porch, during the siege? You said-you said then that you wanted me.”

He leaned back carelessly in his chair and looked into her tense face and his own dark face was inscrutable. Something flickered behind his eyes but he said nothing.

“You said-you said you'd never wanted a woman as much as you wanted me. If you still want me, you can have me. Rhett, I'll do anything you say but, for God's sake, write me a draft for the money! My word's good. I swear it. I won't go back on it. I'll put it in writing if you like.”

He looked at her oddly, still inscrutable and as she hurried on she could not tell if he were amused or repelled. If he would only say something, anything! She felt her cheeks getting hot.

“I have got to have the money soon, Rhett. They'll turn us out in the road and that damned overseer of Father's will own the place and-”

“Just a minute. What makes you think I still want you? What makes you think you are worth three hundred dollars? Most women don't come that high.”

She blushed to her hair line and her humiliation was complete.

“Why are you doing this? Why not let the farm go and live at Miss Pittypat's. You own half that house.”

“Name of God!” she cried. “Are you a fool? I can't let Tara go. It's home. I won't let it go. Not while I've got breath left in me!”

“The Irish,” said he, lowering his chair back to level and removing his hands from his pockets, “are the damnedest race. They put so much emphasis on so many wrong things. Land, for instance. And every bit of earth is just like every other bit. Now, let me get this straight, Scarlett. You are coming to me with a business proposition. I'll give you three hundred dollars and you'll become my mistress.”

“Yes.”

Now that the repulsive word had been said, she felt somehow easier and hope awoke in her again. He had said “I'll give you.” There was a diabolic gleam in his eyes as if something amused him greatly.

“And yet, when I had the effrontery to make you this same proposition, you turned me out of the house. And also you called me a number of very hard names and mentioned in passing that you didn't want a 'passel of brats.' No, my dear, I'm not rubbing it in. I'm only wondering at the peculiarities of your mind. You wouldn't do it for your own pleasure but you will to keep the wolf away from the door. It proves my point that all virtue is merely a matter of prices.”

“Oh, Rhett, how you run on! If you want to insult me, go on and do it but give me the money.”

She was breathing easier now. Being what he was, Rhett would naturally want to torment and insult her as much as possible to pay her back for past slights and for her recent attempted trickery. Well, she could stand it. She could stand anything. Tara was worth it all. For a brief moment it was mid-summer and the afternoon skies were blue and she lay drowsily in the thick clover of Tara's lawn, looking up at the billowing cloud castles, the fragrance of white blossoms in her nose and the pleasant busy humming of bees in her ears. Afternoon and hush and the far-off sound of the wagons coming in from the spiraling red fields. Worth it all, worth more.

Her head went up.

“Are you going to give me the money?”

He looked as if he were enjoying himself and when he spoke there was suave brutality in his voice.

“No, I'm not,” he said.

For a moment her mind could not adjust itself to his words.

“I couldn't give it to you, even if I wanted to. I haven't a cent on me. Not a dollar in Atlanta. I have some money, yes, but not here. And I'm not saying where it is or how much. But if I tried to draw a draft on it, the Yankees would be on me like a duck on a June bug and then neither of us would get it. What do you think of that?”

Her face went an ugly green, freckles suddenly standing out across her nose and her contorted mouth was like Gerald's in a killing rage. She sprang to her feet with an incoherent cry which made the hum of voices in the next room cease suddenly. Swift as a panther, Rhett was beside her, his heavy hand across her mouth, his arm tight about her waist. She struggled against him madly, trying to bite his hand, to kick his legs, to scream her rage, despair, hate, her agony of broken pride. She bent and twisted every way against the iron of his arm, her heart near bursting, her tight stays cutting off her breath. He held her so tightly, so roughly that it hurt and the hand over her mouth pinched into her jaws cruelly. His face was white under its tan, his eyes hard and anxious as he lifted her completely off her feet, swung her up against his chest and sat down in the chair, holding her writhing in his lap.