По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

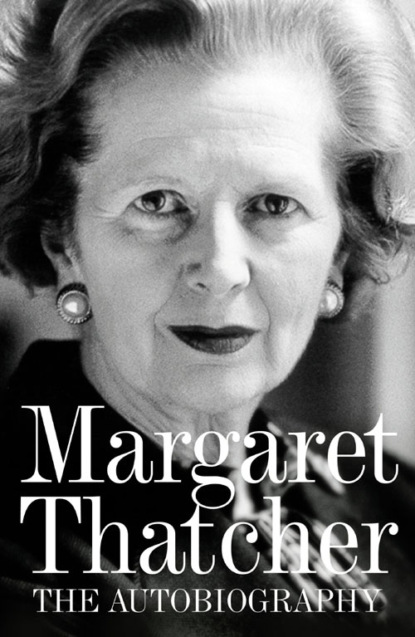

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Perhaps the biggest excitement of my early years was a visit to London when I was twelve years old. I came down by train in the charge of a friend of my mother’s, arriving at King’s Cross, where I was met by the Rev. Skinner and his wife, family friends who were going to look after me. The first impact of London was overwhelming: King’s Cross itself was a giant bustling cavern; the rest of the city had all the dazzle of a commercial and imperial capital. For the first time in my life I saw people from foreign countries, some in the traditional native dress of India and Africa. The sheer volume of traffic and of pedestrians was exhilarating; they seemed to generate a sort of electricity. London’s buildings were impressive for another reason; begrimed with soot, they had a dark imposing magnificence which constantly reminded me that I was at the centre of the world.

I was taken by the Skinners to all the usual sites. I fed the pigeons in Trafalgar Square; I rode the Underground – a slightly forbidding experience for a child; I visited the Zoo, where I rode on an elephant and recoiled from the reptiles – an early portent of my relations with Fleet Street; I was disappointed by Oxford Street, which was much narrower than the boulevard of my imagination; made a pilgrimage to St Paul’s, where John Wesley had prayed on the morning of his conversion; and of course, to the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben, which did not disappoint at all; and I went to look at Downing Street, but unlike the young Harold Wilson did not have the prescience to have my photograph taken outside No. 10.

All this was enjoyable beyond measure. But the high point was my first visit to the Catford Theatre in Lewisham where we saw Sigmund Romberg’s famous musical The Desert Song. For three hours I lived in another world, swept away as was the heroine by the daring Red Shadow – so much so that I bought the score and played it at home, perhaps too often.

I could hardly drag myself away from London or from the Skinners, who had been such indulgent hosts. Their kindness had given me a glimpse of, in Talleyrand’s words, ‘la douceur de la vie’ – how sweet life could be.

Our religion was not only musical and sociable – it was also intellectually stimulating. The ministers were powerful characters with strong views. The general political tendency among Methodists and other Nonconformists in our town was somewhat to the left wing and even pacifist. Methodists in Grantham were prominent in organizing the ‘Peace Ballot’ of 1935, circulating a loaded questionnaire to the electorate, which was then declared overwhelmingly to have ‘voted for peace’. It is not recorded how far Hitler and Mussolini were moved by this result; we had our own views about that in the Roberts household. The Peace Ballot was a foolish idea which must take some of the blame nationally for delaying the rearmament necessary to deter and ultimately defeat the dictators. On this question and others, being staunchly Conservative, we were the odd family out. Our friend the Rev. Skinner was an enthusiast for the Peace Ballot. He was the kindest and holiest man, and he married Denis and me at Wesley’s Chapel in London many years later. But personal virtue is no substitute for political hard-headedness.

The sermons we heard every Sunday made a great impact on me. It was an invited Congregationalist minister, the Rev. Childe, who brought home to me the somewhat advanced notion for those days that whatever the sins of the fathers (and mothers) they must never be visited on the children. I still recall his denunciation of the Pharisaical tendency to brand children born outside marriage as ‘illegitimate’. All the town knew of some children without fathers; listening to the Rev. Childe, we felt very guilty about thinking of them as different. Times have changed. We have since removed the stigma of illegitimacy not only from the child but also from the parent – and perhaps increased the number of disadvantaged children thereby. We still have to find some way of combining Christian charity with sensible social policy.

When war broke out and death seemed closer to everybody, the sermons became more telling. In one, just after the Battle of Britain, the preacher told us that it is ‘always the few who save the many’: so it was with Christ and the apostles. I was also inspired by the theme of another sermon: history showed how it was those who were born at the depths of one great crisis who would be able to cope with the next. This was proof of God’s benevolent providence and a foundation for optimism about the future, however dark things now looked. The values instilled in church were faithfully reflected in my home.

So was the emphasis on hard work. In my family we were never idle – partly because idleness was a sin, partly because there was so much work to be done, and partly, no doubt, because we were just that sort of people. As I have mentioned, I would help whenever necessary in the shop. But I also learned from my mother just what it meant to cope with a household so that everything worked like clockwork, even though she had to spend so many hours serving behind the counter. Although we had a maid before the war – and later a cleaning lady a couple of days a week – my mother did much of the work herself, and there was a great deal more than in a modern home. She showed me how to iron a man’s shirt in the correct way and to press embroidery without damaging it. Large flatirons were heated over the fire and I was let in on the secret of how to give a special finish to linen by putting just enough candle wax to cover a sixpenny piece on the iron. Most unusually for those times, at my secondary school we had to study domestic science – everything from how to do laundry properly to the management of the household budget. So I was doubly equipped to lend a hand with the domestic chores. The whole house at North Parade was not just cleaned daily and weekly: a great annual spring clean was intended to get to all those parts which other cleaning could not reach. Carpets were taken up and beaten. The mahogany furniture – always good quality, which my mother had bought in auction sales – was washed down with a mixture of warm water and vinegar before being repolished. Since this was also the time of the annual stocktaking in the shop, there was hardly time to draw breath.

Nothing in our house was wasted, and we always lived within our means. The worst you could say about another family was that they ‘lived up to the hilt’. Because we had always been used to a careful regime, we could cope with wartime rationing, though we used to note down the hints on the radio about the preparation of such stodgy treats as ‘Lord Woolton’s potato pie’, an economy dish named after the wartime Minister for Food. My mother was an excellent cook and a highly organized one. Twice a week she had her big bake – bread, pastry, cakes and pies. Her home-made bread was famous, as were her Grantham gingerbreads. Before the war there were roasts on Sunday, which became cold cuts on Monday and disappeared into rissoles on Tuesday. With wartime, however, the Sunday roast became almost meatless stew or macaroni cheese.

Small provincial towns in those days had their own networks of private charity. In the run-up to Christmas as many as 150 parcels were made up in our shop, containing tinned meat, Christmas cake and pudding, jam and tea – all purchased for poorer families by one of the strongest social and charitable institutions in Grantham, the Rotary Club. There was always something from those Thursday or Sunday bakes which was sent out to elderly folk living alone or who were sick. As grocers, we knew something about the circumstances of our customers.

Clothes were never a problem for us. My mother had been a professional seamstress and made most of what we wore. In those days there were two very good pattern services, Vogue and Butterick’s, and in the sales we could get the best-quality fabrics at reduced prices. So we got excellent value for money and were, by Grantham standards, rather fashionable. For my father’s mayoral year, my mother made both her daughters new dresses – a blue velvet for my sister and a dark green velvet for me – and herself a black moiré silk gown. But in wartime the ethos of frugality was almost an obsession. Even my mother and I were taken aback by one of our friends, who told us that she never threw away her tacking cottons but re-used them: ‘I consider it my duty to do so,’ she said. After that, so did we. We were not Methodists for nothing.

I had less leisure time than other children. But I used to enjoy going for long walks, often on my own. Grantham lies in a little hollow surrounded by hills, unlike most of Lincolnshire which is very flat. I loved the beauty of the countryside and being alone with my thoughts in those surroundings. Sometimes I used to walk out of the town by Manthorpe Road and cut across on the north side to return down the Great North Road. I would also walk up Hall’s Hill, where in wartime we were given a week off school to go and gather rose hips and blackberries. There was tobogganing there when it snowed.

I did not play much sport, though I learned to swim, and at school I was a somewhat erratic hockey player. At home we played the usual games, like Monopoly and Pit – a noisy game based on the Chicago Commodities Exchange. In a later visit to America I visited the Exchange; but my dabbling in commodities ended there.

It was, however, the coming of the cinema to Grantham which really brightened my life. We were fortunate in having among our customers the Campbell family who owned three cinemas in Grantham. They would sometimes invite me around to their house to play the gramophone, and I got to know their daughter Judy, later to be a successful actress who partnered Noël Coward in his wartime comedy Present Laughter and made famous the song ‘A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square’. Because we knew the Campbells, the cinema was more acceptable to my parents than it might otherwise have been. They were content that I should go to ‘good’ films, a classification which fortunately included Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals, and the films of Alexander Korda. They rarely went with me – though on a Bank Holiday we would go together to the repertory theatre in Nottingham or to one of the big cinemas there – so usually I would be accompanied by friends of my own age. Even then, however, there were limits. Ordinarily there was a new film each week; but since some of these did not sustain enough interest to last six days, another one was shown from Thursday. Some people would go along to the second film, but that was greatly frowned on in our household.

Perhaps that was a fortunate restraint; for I was entranced with the romantic world of Hollywood. For 9d you had a comfortable seat in the darkness while the screen showed first the trailer for forthcoming attractions, then the British Movietone News with its chirpy optimistic commentary, after that a short public service film on a theme like Crime Does Not Pay, and finally the Big Picture. These ran the gamut from imperialistic adventures like The Four Feathers and Drum, to sophisticated comedies like The Women (with every female star in the business), to the four-handkerchief weepies like Barbara Stanwyck in Stella Dallas or Ingrid Bergman in anything. Nor was I entirely neglecting my political education ‘at the pictures’. My views on the French Revolution were gloriously confirmed by Leslie Howard and lovely Merle Oberon in The Scarlet Pimpernel. I saw my father’s emphasis on the importance of standing up for your principles embodied by James Stewart in Mr Smith Goes to Washington. I rejoiced to see Soviet communism laughed out of court when Garbo, a stern Commissar, was seduced by a lady’s hat in Ninotchka.

And my grasp of history was not made more difficult by the fact that William Pitt the Younger was played by Robert Donat and, in Marie Walewska, Napoleon was played by the great French charmer Charles Boyer.

I often reflect how fortunate I was to have been born in 1925 and not twenty years earlier. Until the 1930s, there was no way that a young girl living in a small English provincial town could have had access to this extraordinary range of talent, dramatic form, human emotion, sex appeal, spectacle and style. To a girl born twenty years later these offerings were commonplace and taken much more for granted. Grantham was a small town, but on my visits to the cinema I roamed to the most fabulous realms of the imagination. It gave me the determination to roam in reality one day.

For my parents the reality which mattered was here and now. Yet it was not really a dislike of pleasure which shaped their attitude. They made a very important distinction between mass and self-made entertainment, which is just as valid in the age of constant soap operas and game shows – perhaps more so. They felt that entertainment that demanded something of you was preferable to being a passive spectator. At times I found this irksome, but I also understood the essential point.

When my mother, sister and I went on holiday together, usually to Skegness, there was always the same emphasis on being active, rather than sitting around day-dreaming. We would stay in a self-catering guesthouse, much better value than a hotel, and first thing in the morning I went out with the other children for PT exercises arranged in the public gardens. There was plenty to keep us occupied and, of course, there were buckets and spades and the beach. In the evening we would go to the variety shows and reviews, with comedians, jugglers, acrobats, ‘old tyme’ singers, ventriloquists and lots of audience participation when we joined in singing the latest hit from Henry Hall’s Guest Night. My parents considered that such shows were perfectly acceptable, which in itself showed how attitudes changed: we would never have gone to the variety while Grandmother Stephenson, who lived with us till I was ten, was still alive.

That may make my grandmother sound rather forbidding. Again, not at all. She was a warm presence in the life of myself and my sister. Dressed in the grandmotherly style of those days – long black sateen-beaded dress – she would come up to our bedrooms on warm summer evenings and tell us stories of her life as a young girl. She would also make our flesh creep with old wives’ tales of how earwigs would crawl under your skin and form carbuncles. Her death at the age of eighty-six was the first time I had ever encountered death. As was the custom in those days, I was sent to stay with friends until the funeral was over and my grandmother’s belongings had all been packed away. In fact, life is very much a day-today experience for a child, and I recovered reasonably quickly. But Mother and I went to tend her grave on half-day closing days. I never knew either of my grandfathers, who died before I was born, and I saw Grandmother Roberts only twice, on holidays down to Ringstead in Northamptonshire. She was a bustling, active little old lady who kept a fine garden. I remember particularly that she kept a store of Cox’s orange pippins in an upstairs room from which my sister and I were invited to select the best.

My father was a great bowls player, and he smoked (which was very bad for him because of his weak chest). Otherwise, his leisure and entertainment always seemed to merge into duty. We had no alcohol in the house until he became mayor at the end of the war, and then only sherry and cherry brandy, which for some mysterious reason was considered more respectable than straight brandy, to entertain visitors. (Years of electioneering also later taught me that cherry brandy is very good for the throat.)

Like the other leading businessmen in Grantham, my father was a Rotarian. The Rotary motto, ‘Service Above Self’, was engraved on his heart. He spoke frequently and eloquently at Rotary functions, and we could read his speeches reported at length in the local paper. The Rotary Club was constantly engaged in fund raising for the town’s different charities. My father would be involved in similar activity, not just through the church but as a councillor and in a private capacity. One such event which I used to enjoy was the League of Pity (now NSPCC) Children’s Christmas party, which I would go to in one of the party dresses beautifully made by my mother, to raise money for children who needed help.

Apart from home and church, the other centre of my life was, naturally enough, school. Here too I was very lucky. Huntingtower Road Primary School had a good reputation in the town and by the time I went there I had already been taught simple reading by my parents. Even when I was very young I enjoyed learning. Like all children, I suspect, these days remain vividly immediate for me. I remember a heart-stopping moment at the age of five when I was asked how to pronounce W-R-A-P; I got it right, but I thought ‘They always give me the difficult ones.’ Later, in General Knowledge, I first came across the mystery of ‘proverbs’. I already had a logical and indeed somewhat literal mind – perhaps I have not changed much in this regard – and I was perplexed by the metaphorical element of phrases like ‘Look before you leap’. I thought it would be far better to say ‘Look before you cross’ – a highly practical point given the dangerous road I must traverse on my way to school. And I triumphantly pointed out the contradiction between that proverb and ‘He who hesitates is lost’.

It was in the top class at primary school that I first came across the work of Kipling, who died that January of 1936. I immediately became fascinated by his poems and stories and asked my parents for a Kipling book at Christmas. His poems gave a child access to a wider world – indeed, wider worlds – of the Empire, work, English history and the animal kingdom. Like the Hollywood films later, Kipling offered glimpses into the romantic possibilities of life outside Grantham. By now I was probably reading more widely than most of my classmates, doubtless through my father’s influence, and it showed on occasion. I can still recall writing an essay about Kipling and burning with indignation at being accused of having copied down the word ‘nostalgia’ from some book, whereas I had used it quite naturally and easily.

From Huntingtower Road I went on to Kesteven and Grantham Girls’ School. It was in a different part of town, and what with coming home for lunch, which was more economical than the school lunch, I walked four miles a day back and forth. Our uniform was saxe-blue and navy and so we were called ‘the girls in blue’. (When Camden Girls’ School from London was evacuated to Grantham for part of the war they were referred to as ‘the girls in green’.) The headmistress was Miss Williams, a petite, upright, grey-haired lady, who had started the school as headmistress in 1910, inaugurated certain traditions such as that all girls however academic had to take domestic science for four years, and whose quiet authority by now dominated everything. I greatly admired the special outfits Miss Williams used to wear at the annual school fête or prize-giving, when she appeared in beautiful silk, softly tailored, looking supremely elegant. But she was very practical. The advice to us was never to buy a low-quality silk when the same amount of money would purchase a good-quality cotton. ‘Never aspire to a cheap fur coat when a well-tailored wool coat would be a better buy.’ The rule was always to go for quality within your own income.

My teachers had a genuine sense of vocation and were highly respected by the whole community. The school was small enough – about 350 girls – for us to get to know them and one another, within limits. The girls were generally from middle-class backgrounds; but that covered a fairly wide range of occupations from town and country. My closest friend came in daily from a rural village about ten miles distant, where her father was a builder. I used to stay with her family from time to time. Her parents, no less keen than mine to add to a daughter’s education, would take us out for rural walks, identifying the wild flowers and the species of birds and birdsongs.

I had a particularly inspiring History teacher, Miss Harding, who gave me a taste for the subject, which, unfortunately, I never fully developed. I found myself with absolute recall remembering her account of the Dardanelles campaign so many years later when, as Prime Minister, I walked over the tragic battlegrounds of Gallipoli.

But the main academic influence on me was undoubtedly Miss Kay, who taught Chemistry, in which I decided to specialize. It was not unusual – in an all-girls’ school, at least – for a girl to concentrate on science, even before the war. My natural enthusiasm for the sciences was whetted by reports of breakthroughs in the splitting of the atom and the development of plastics. It was clear that a whole new scientific world was opening up. I wanted to be part of it. Moreover, as I knew that I would have to earn my own living, this seemed an exciting way to do so.

As my father had left school at the age of thirteen, he was determined to make up for this and to see that I took advantage of every educational opportunity. We would both go to hear ‘Extension Lectures’ from the University of Nottingham about current and international affairs, which were given in Grantham regularly. After the talk would come a lively question time in which I and many others would take part: I remember, in particular, questions from a local RAF man, Wing-Commander Millington, who later captured Chelmsford for Common Wealth – a left-wing party of middle-class protest – from the Churchill coalition in a by-election towards the end of the war.

My parents took a close interest in my schooling. Homework always had to be completed – even if that meant doing it on Sunday evening. During the war, when the Camden girls were evacuated to Grantham and a shift system was used for teaching at our school, it was necessary to put in extra hours at the weekend. My father, in particular, who was an all the more avid reader for being a self-taught scholar, would discuss what we read at school. On one occasion he found that I did not know Walt Whitman’s poetry; this was quickly remedied, and Whitman is still a favourite author of mine. I was also encouraged to read the classics – the Brontës, Jane Austen and, of course, Dickens: it was the latter’s A Tale of Two Cities, with its strong political flavour, that I liked best. My father also used to subscribe to the Hibbert Journal – a philosophical journal. But this I found heavy going.

Beyond home, church and school lay the community which was Grantham itself. We were immensely proud of our town; we knew its history and traditions; we were glad to be part of its life. Grantham was established in Saxon times, though it was the Danes who made it an important regional centre. During the twelfth century the Great North Road was re-routed to run through the town, literally putting Grantham on the map. Communications were always the town’s lifeblood. In the eighteenth century the canal was cut to carry coke, coal and gravel into Grantham and corn, malt, flour and wool out of it. But the real expansion had come with the arrival of the railways in 1850.

Our town’s most imposing structure I have already mentioned – the spire of St Wulfram’s Church, which could be seen from all directions. But most characteristic and significant for us was the splendid Victorian Guildhall and, in front of it, the statue of Grantham’s most famous son, Sir Isaac Newton. It was from here, on St Peter’s Hill, that the Remembrance Day parades began to process en route to St Wulfram’s. I would watch from the windows of the Guildhall Ballroom as (preceded by the Salvation Army band and the band from Ruston and Hornsby’s locomotive works) the mayor, aldermen and councillors with robes and regalia, followed by Brownies, Cubs, Boys’ Brigade, Boy Scouts, Girl Guides, Freemasons, Rotary, Chamber of Commerce, Working Men’s Clubs, trade unions, British Legion, soldiers, airmen, the Red Cross, the St John’s Ambulance and representatives of every organization which made up our rich civic life filed past. It was also on the green at St Peter’s Hill that every Boxing Day we gathered to watch the pink coats of the Belvoir Hunt hold their meet (followed by the traditional tipple) and cheered them as they set off.

Nineteen thirty-five was a quite exceptional and memorable year for the town. We celebrated King George V’s Silver Jubilee along with Grantham’s Centenary as a borough. Lord Brownlow, whose family (the Custs) with the Manners family (the Dukes of Rutland) were the most distinguished aristocratic patrons of the town, became mayor. The town itself was heavily decorated with blue and gold waxed streamers – our local colours – across the main streets. Different streets vied to outdo one another in the show they put on. I recall that it was the street with some of the poorest families in the worst housing, Vere Court, which was most attractively turned out. Everyone made an effort. The brass bands played throughout the day, and Grantham’s own ‘Carnival Band’ – a rather daring innovation borrowed from the United States and called ‘The Grantham Gingerbreads’ – added to the gaiety of the proceedings. The schools took part in a great open-air programme and we marched in perfect formation under the watchful eye of the wife of the headmaster of the boys’ grammar school to form the letters ‘G-R-A-N-T-H-A-M’. Appropriately enough, I was part of the ‘M’.

My father’s position as a councillor, Chairman of the Borough Finance Committee, then alderman* (#ulink_a0b12f4a-cd0e-5965-a8d7-63e913745ed4) and finally, in 1945–46, mayor meant that I heard a great deal about the town’s business and knew those involved in it. Politics was a matter of civic duty and party was of secondary importance. The Labour councillors we knew were respected and, whatever the battles in the council chamber or at election time, they came to our shop and there was no partisan bitterness. My father understood that politics has limits – an insight which is all too rare among politicians. His politics would perhaps be best described as ‘old-fashioned liberal’. Individual responsibility was his watchword and sound finance his passion. He was an admirer of John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. Like many other business people he had, as it were, been left behind by the Liberal Party’s acceptance of collectivism. He stood for the council as a ratepayer’s candidate. In those days, before comprehensive schools became an issue and before the general advance of Labour politics into local government, local council work was considered as properly non-partisan. But I never remember him as anything other than a staunch Conservative.

I still recall with great sorrow the day in 1952 when Labour, having won the council elections, voted my father out as an alderman. This was roundly condemned at the time for putting party above community. Nor can I forget the dignity with which he behaved. After the vote in the council chamber was taken, he rose to speak: ‘It is now almost nine years since I took up these robes in honour, and now I trust in honour they are laid down.’ And later, after receiving hundreds of messages from friends, allies and even old opponents, he issued a statement which said: ‘Although I have toppled over I have fallen on my feet. My own feeling is that I was content to be in and I am content to be out.’ Years later, when something not too dissimilar happened to me, after my father was long dead, I tried to take as an example the way he left public life.

But this is to anticipate. Perhaps the main interest which my father and I shared while I was a girl was a thirst for knowledge about politics and public affairs. We read the Daily Telegraph every day, The Methodist Recorder, Picture Post and John O’London’s Weekly every week, and when we were small we took The Children’s Newspaper. Occasionally we read The Times.

And then came the day my father bought our first wireless – a Philips of the kind you sometimes now see in the less pretentious antique shops. I knew what he was planning and ran much of the way home from school in my excitement. I was not disappointed. It changed our lives. From then on it was not just Rotary, church and shop which provided the rhythm of our day: it was the radio news. And not just the news. During the war after the 9 o’clock news on Sundays there was Postscript, a short talk on a topical subject, often by J.B. Priestley, who had a unique gift of cloaking left-wing views as solid, down-to-earth, Northern homespun philosophy, and sometimes an American journalist called Quentin Reynolds who derisively referred to Hitler by one of his family names, ‘Mr Schicklgruber’. There was The Brains Trust, an hour-long discussion of current affairs by four intellectuals, of whom the most famous was Professor C.E.M. Joad, whose answer to any question always began ‘It all depends what you mean by …’ On Friday evenings there were commentaries by people like Norman Birkett in the series called Encounter. I loved the comedy ITMA with its still serviceable catchphrases and its cast of characters like the gloomy charlady ‘Mona Lott’ and her signature line ‘It’s being so cheerful as keeps me going.’

As for so many families, the unprecedented immediacy of radio broadcasts gave special poignancy to great events – particularly those of wartime. I recall sitting by our radio with my family at Christmas dinner and listening to the King’s broadcast in 1939. We knew how he struggled to overcome his speech impediment and we knew that the broadcast was live. I found myself thinking just how miserable he must have felt, not able to enjoy his own Christmas dinner, knowing that he would have to broadcast. I remember his slow voice reciting those famous lines:

And I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year: ‘Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.’

And he replied: ‘Go out into the darkness and put your hand into the Hand of God. That shall be to you better than light and safer than a known way.’* (#ulink_2cd96d81-4bcf-5e48-8a64-af6c7ea08c8d)

I was almost fourteen by the time war broke out, and already informed enough to understand the background to it and to follow closely the great events of the next six years. My grasp of what was happening in the political world during the thirties was less sure. But certain things I did take in. The years of the Depression – the first but not the last economic catastrophe resulting from misguided monetary policy – had less effect on Grantham itself than on the surrounding agricultural communities, and of course much less than on Northern towns dependent on heavy industry. Most of the town’s factories kept going – the largest, Ruston and Hornsby, making locomotives and steam engines. We even attracted new investment, partly through my father’s efforts: Aveling-Barford built a factory to make steamrollers and tractors. Our family business was also secure: people always have to eat, and our shops were well run. The real distinction in the town was between those who drew salaries for what today would be called ‘white collar’ employment and those who did not, with the latter being in a far more precarious position as jobs became harder to get. On my way to school I would pass a long queue waiting at the Labour Exchange, seeking work or claiming the dole. We were lucky in that none of our closest friends was unemployed, but we knew people who were. We also knew – and I have never forgotten – how neatly turned out the children of those unemployed families were. Their parents were determined to make the sacrifices that were necessary for them. The spirit of self-reliance and independence was very strong in even the poorest people of the East Midlands towns and, because others quietly gave what they could, the community remained together. Looking back, I realize just what a decent place Grantham was.

So I did not grow up with the sense of division and conflict between classes. Even in the Depression there were many things which bound us all together. The monarchy was certainly one. And my family like most others was immensely proud of the Empire. We felt that it had brought law, good administration and order to lands which would never otherwise have known them. I had a romantic fascination for out-of-the-way countries and continents and what benefits we British could bring to them. As a child, I heard with wonder a Methodist missionary describing his work in Central America with a tribe so primitive that they had never written down their language until he did it for them. Later, I seriously considered going into the Indian Civil Service, for to me the Indian Empire represented one of Britain’s greatest achievements. (I had no interest in being a civil servant in Britain.) But my father said, all too perceptively as it turned out, that by the time I was ready to join it the Indian Civil Service would probably not exist.

As for the international scene, I recall when I was very young my parents expressing unease about the weakness of the League of Nations and its failure to come to the aid of Abyssinia when Italy invaded it in 1935. We had a deep distrust of the dictators.

We did not know much about the ideology of communism and fascism at this time. But, unlike many conservative-minded people, my father was fierce in rejecting the argument that fascist regimes had to be backed as the only way to defeat communists. He believed that the free society was the better alternative to both. This too was a conviction I quickly made my own. Well before war was declared, we knew just what we thought of Hitler. On the cinema newsreels I would watch with distaste and incomprehension the rallies of strutting brownshirts, so different from the gentle self-regulation of our own civic life. We also read a good deal about the barbarities and absurdities of the Nazi regime.

But none of this meant, of course, that we viewed war with the dictators as anything other than an appalling prospect, which should be avoided if possible. In our attic there was a trunk full of magazines showing, among other things, the famous picture from the Great War of a line of British soldiers blinded by mustard gas walking to the dressing station, each with a hand on the shoulder of the one in front to guide him. Hoping for the best, we prepared for the worst. As early as September 1938 – the time of Munich – my mother and I went out to buy yards of blackout material. My father was heavily involved in organizing the town’s air raid precautions. As he would later say, ‘ARP’ stood for ‘Alf Roberts’ Purgatory’, because it was taking up so much time that he had none to spare for other things.

The most pervasive myth about the thirties is perhaps that it was the Right rather than the Left which most enthusiastically favoured appeasement. Not just from my own experience in a highly political right-wing family, but from my recollection of how Labour actually voted against conscription even after the Germans marched into Prague, I have never been prepared to swallow this. But it is important to remember that the atmosphere of the time was so strongly pacifist that the practical political options were limited.

The scale of the problem was demonstrated in the general election of 1935 – the contest in which I cut my teeth politically, at the age of ten. It will already be clear that we were a highly political family. And for all the serious sense of duty which underlay it, politics was fun. I was too young to canvass for my father during council elections, but I was put to work folding the bright red election leaflets extolling the merits of the Conservative candidate, Sir Victor Warrender. The red came off on my sticky fingers and someone said, ‘There’s Lady Warrender’s lipstick.’ I had no doubt at all about the importance of seeing Sir Victor returned. On election day itself, I was charged with the responsible task of running back and forth between the Conservative committee room and the polling station (our school) with information about who had voted. Our candidate won, though with a majority down from 16,000 to 6,000.

I did not grasp at the time the arguments about rearmament and the League of Nations, but this was a very tough election, fought in the teeth of opposition from the enthusiasts of the Peace Ballot and with the Abyssinian war in the background. Later, in my teens, I used to have fierce arguments with other Conservatives about whether Baldwin had culpably misled the electorate during the campaign in not telling them the dangers the country faced. In fact, had the National Government not been returned at that election there is no possibility that rearmament would have happened faster, and it is very likely that Labour would have done less. Nor could the League have ever prevented a major war.

We had mixed feelings about the Munich Agreement of September 1938, as did many people. At the time, it was impossible not to be pulled in two directions. We knew by now a good deal about Hitler’s regime and probable intentions – something brought home to my family by the fact that Hitler had crushed Rotary in Germany, which my father always considered one of the greatest tributes Rotary could ever be paid. Dictators, we learned, could no more tolerate Burke’s ‘little platoons’ – the voluntary bodies which help make up civil society – than they could individual rights under the law. Dr Jauch, of German extraction and probably the town’s best doctor, received a lot of information from Germany which he passed on to my father, and he in turn discussed it with me.

I knew just what I thought of Hitler. Near our house was a fish and chip shop where I was sent to buy our Friday evening meal. Fish and chip queues were always a good forum for debate. On one occasion the topic was Hitler. Someone suggested that at least he had given Germany some self-respect and made the trains run on time. I vigorously argued the opposite, to the astonishment and doubtless irritation of my elders. The woman who ran the shop laughed and said: ‘Oh, she’s always debating.’