По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

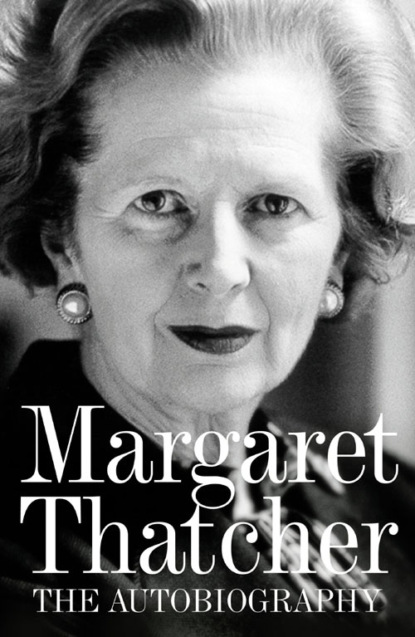

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The most reliable sign that a political occasion has gone well is that you have enjoyed it. I enjoyed that evening at Dartford, and the outcome justified my confidence. I was selected. Afterwards I stayed behind for drinks and something to eat with the officers of the Association. The candidate is not the only one to be overwhelmed by relief on these occasions. The selectors too can stop acting as critics and start to become friends. The happy, if still slightly bewildered young candidate, is deluged with advice, information and offers of help. Such friendly occasions provide at least part of the answer to that question put to all professional politicians: ‘Why on earth do you do it?’

My next step was to be approved by the national Party. Usually Party approval precedes selection, but when I went to Central Office the day after to meet the Women’s Chairman, Miss Marjorie Maxse, I had no difficulties. A few weeks afterwards I was invited to dinner to meet the Party Chairman Lord Woolton, his deputy J.P.L. Thomas, Miss Maxse and the Area Agent, Miss Beryl Cook. Over the next few years Marjorie Maxse and Beryl Cook proved to be strong supporters and they gave me much useful advice.

After selection comes adoption. The formal adoption meeting is the first opportunity a candidate has to impress him or herself on the rank and file of the Association. It is therefore a psychologically important occasion. It is also a chance to gain some good local publicity, for the press are invited too. Perhaps what meant most to me, however, was the presence of my father. For the first time he and I stood on the same platform to address a meeting. He recalled how his family had always been Liberal, but that now it was the Conservatives who stood for the old Liberalism. In my own speech I too took up a theme which was Gladstonian in content if not quite style (or length), urging that ‘the Government should do what any good housewife would do if money was short – look at their accounts and see what’s wrong’.

After the adoption meeting at the end of February I was invited back by two leading lights of the Association, Mr and Mrs Soward, to a supper party they had arranged in my honour. Their house was at the Erith end of the constituency, not far from the factory of the Atlas Preservative Company, which made paint and chemicals, where Stanley Soward was a director. His boss, the Managing Director, had been at my adoption meeting and was one of the dinner guests: and so it was that I met Denis.

It was clear to me at once that Denis was an exceptional man. He knew at least as much about politics as I did and a good deal more about economics. His professional interest in paint and mine in plastics may seem an unromantic foundation for friendship, but it also enabled us right away to establish a joint interest in science. And as the evening wore on I discovered that his views were no-nonsense Conservatism.

After the evening was over he drove me back to London so that I could catch the midnight train to Colchester. It was not a long drive at that time of night, but long enough to find that we had still more in common. Denis is an avid reader, especially of history, biography and detective novels. He seemed to have read every article in the Economist and the Banker, and we found that we both enjoyed music – Denis with his love of opera, and me with mine of choral music.

From then on we met from time to time at constituency functions, and began to see more of each other outside the constituency. He had a certain style and dash. He had a penchant for fast cars and drove a Jaguar and, being ten years older, he simply knew more of the world than I did. At first our meetings revolved around political discussion. But as we saw more of each other, we started going to the occasional play and had dinner together. Like any couple, we had our favourite restaurants, small pasta places in Soho for normal dates, the wonderful White Tower in Fitzrovia, the Ecu de France in Jermyn Street and The Ivy for special occasions. I was very flattered by Denis’s attentions, but I first began to suspect he might be serious when the Christmas after my first election campaign at Dartford I received from him a charming present of a crystal powder bowl with a silver top, which I still treasure.

We might perhaps have got married sooner, but my passion for politics and his for rugby football – Saturdays were never available for a date – both got in the way. He more than made up for this by being an immense help in the constituency – problems were solved in a trice and all the logistics taken care of. Indeed, the fact that he had proposed to me and that we had become engaged was one final inadvertent political service, because unbeknown to me Beryl Cook leaked the news just before election day to give my campaign a final boost.

When Denis asked me to be his wife, I thought long and hard about it. I had so much set my heart on politics that I really hadn’t figured marriage in my plans. I suppose I pushed it to the back of my mind and simply assumed that it would occur of its own accord at some time in the future. I know that Denis too, because a wartime marriage had ended in divorce, only asked me to be his wife after much reflection. But the more I considered, the surer I was. More than forty years later I know that my decision to say ‘yes’ was one of the best I ever made.

I had in any case been thinking of leaving BX Plastics and Colchester for some time. It was my selection for Dartford that persuaded me I had to look for a new job in London. I had told the Selection Committee that I would fight Dartford with all the energy at my disposal, and I meant it. Nor was I temperamentally inclined to do otherwise. So I began to look for a London-based job which would give me about £500 a year – not a princely sum even in those days, but one which would allow me to live comfortably if modestly. I went for several interviews, but found that they were not keen to take on someone who was hoping to leave to take up a political career. I was certainly not going to disguise my political ambitions, so I just kept on looking. Finally, I was taken on by J. Lyons in Hammersmith as a food research chemist and moved into lodgings in the constituency.

Dartford became my home in every sense. The families I lived with fussed over me and could not have been kinder, their natural good nature undoubtedly supplemented by the fact that they were ardent Tories. The Millers also took me under their wing. After evening meetings I would regularly go back to their house to unwind over a cup of coffee. It was a cheerful household in which everyone seemed to be determined to enjoy themselves after the worst of the wartime stringencies were over. We regularly went out to political and non-political functions, and the ladies made an extra effort to wear something smart. John Miller’s father – a widower – lived with the family and was a great friend to me: whenever there was a party he would send me a pink carnation as a buttonhole.

I also used to drive out to the neighbouring North Kent constituencies: the four Associations – Dartford, Bexley Heath (where Ted Heath was the candidate), Chislehurst (Pat Hornsby-Smith) and Gravesend (John Lowe) – worked closely together and had a joint President in Morris Wheeler. From time to time he would bring us all together at his large house, ‘Franks’, at Horton Kirby.

Of the four constituencies, Dartford was by far the least winnable, and therefore doubtless in the eyes of its neighbours – though not Dartford’s – the least important. But there is always good political sense in linking safe constituencies with hopeless cases. If an active organization can be built up in the latter there is a good chance of drawing away your opponents’ party workers from the political territory you need to hold. This was one of the services which Central Office expected of us to help Ted Heath in the winnable seat of Bexley.

It was thus that I met Ted. He was already the candidate for Bexley, and Central Office asked me to speak in the constituency. Ted was an established figure. He had fought in the war, ending up as a Lieutenant-Colonel; his political experience went back to the late 1930s when he had supported an anti-Munich candidate in the Oxford by-election; and he had won the respect of Central Office and the four Associations. When we met I was struck by his crisp and logical approach – he always seemed to have a list of four aims, or five methods of attack. Though friendly with his constituency workers, he was always very much the man in charge, ‘the candidate’, or ‘the Member’, and this made him seem, even when at his most affable, somewhat aloof and alone.

Pat Hornsby-Smith, his next-door neighbour at Chislehurst, could not have been a greater contrast. She was a fiery, vivacious redhead and perhaps the star woman politician of the time. She had brought the Tory Conference to its feet with a rousing right-wing speech in 1946, and was always ready to lend a hand to other young colleagues. She and I became great friends, and had long political talks at her informal supper parties.

Well before the 1950 election we were all conscious of a Conservative revival. This was less the result of fundamental rethinking within the Conservative Party than of a strong reaction both among Conservatives and in the country at large against the socialism of the Attlee Government.

The 1950 election campaign was the most exhausting few weeks I had ever spent. Unlike today’s election campaigns, we had well-attended public meetings almost every night, and so I would have to prepare my speech some time during the day. I also wrote my letters to prospective constituents. Then, most afternoons, it was a matter of doorstep canvassing and, as a little light relief, blaring out the message by megaphone. I was well supported by my family: my father came to speak and my sister to help.

Before the election Lady Williams (wife of Sir Herbert Williams, veteran tariff reformer and a Croydon MP for many years) told candidates that we should make a special effort to identify ourselves by the particular way we dressed when we were campaigning. I took this very seriously and spent my days in a tailored black suit and a hat which I bought in Bourne and Hollingsworth in Oxford Street specially for the occasion. And, just to make sure, I put a black and white ribbon around it with some blue inside the bow. Quite whether these precautions were necessary is another matter. How many other twenty-four-year-old girls could be found standing on a soapbox in Erith Shopping Centre? In those days it was not often done for women candidates to canvass in factories. But I did – inside and outside. There was always a lively if sometimes noisy reception. The socialists in Dartford became quite irked until it turned out that their candidate – the sitting MP Norman Dodds – would have had the same facilities extended to him if they had thought of asking. It was only the pubs that I did not like going into, and indeed would not do so alone. Some inhibitions die hard.

I was lucky to have an opponent like Norman Dodds, a genuine and extremely chivalrous socialist of the old school. He knew that he was going to win, and he was a big enough man to give an ambitious young woman with totally different opinions a chance. Soon after I was adopted he challenged me to a debate in the hall of the local grammar school and, of course, I eagerly accepted. He and I made opening speeches, there were questions and then we each wound up our case. Each side had its own supporters, and the noise was terrific. Later in the campaign there was an equally vigorous and inconclusive re-run. What made it all such fun was that the argument was about issues and facts, not personalities. On one occasion, a national newspaper reported that Norman Dodds thought a great deal of my beauty but not a lot of my election chances – or of my brains. This perfect socialist gentleman promptly wrote to me disclaiming the statement – or at least the last part.

My own public meetings were also well attended. It was not unusual for the doors of our hall to be closed twenty minutes before the meeting was due to start because so many people were crowding in. Certainly, in those days one advantage of being a woman was that there was a basic courtesy towards us on which we could draw – something which today’s feminists have largely dissipated. So, for example, on one occasion I arrived at a public meeting to find the visiting speaker, the former Air Minister Lord Balfour of Inchrye, facing a minor revolution from hecklers in the audience – to such an extent indeed that the police had been sent for. I told the organizers to cancel the request, and sure enough once I took my place on the platform and started to speak the tumult subsided and order – if not exactly harmony – was restored.

I was also fortunate in the national and indeed international publicity which my candidature received. At twenty-four, I was the youngest woman candidate fighting the 1950 campaign, and as such was an obvious subject for comment. I was asked to write on the role of women in politics. My photograph made its way into Life magazine, the Illustrated London News where it rubbed shoulders with those of the great men of politics, and even the West German press where I was described as a ‘junge Dame mit Charme’ (perhaps for the last time).

The slogans, coined by me, gained in directness whatever they lacked in subtlety – ‘Vote Right to Keep What’s Left’ and, still more to the point, ‘Stop the Rot, Sack the Lot’.

I felt that our hard work had been worthwhile when I heard the result at the count in the local grammar school. I had cut the Labour majority by 6,000. It was in the early hours at Lord Camrose’s Daily Telegraph party at the Savoy Hotel – to which candidates, MPs, ministers, Opposition figures and social dignitaries were in those days all invited – that I experienced the same bittersweet feeling about the national result, where the Conservatives had cut Labour’s overall majority from 146 to 5 seats. But victory it was not.

I should recall, however, one peculiar experience I had as candidate for Dartford. I was asked to open a Conservative fête in Orpington and was reluctantly persuaded to have my fortune told while I was there. Some fortune tellers have a preference for crystal balls. This one apparently preferred jewellery. I was told to take off my string of pearls so that they could be felt and rubbed as a source of supernatural inspiration. The message received was certainly optimistic: ‘You will be great – great as Churchill.’ Most politicians have a superstitious streak; even so, this struck me as quite ridiculous. Still, so much turns on luck that anything that seems to bring a little with it is more than welcome. From then on I regarded my pearls as lucky. And, all in all, they seem to have proved so.

As I have said, the 1950 result was inconclusive. After the initial exhilaration dies away such results leave all concerned with a sense of anti-climax. There seemed little doubt that Labour had been fatally wounded and that the coup de grâce would be administered in a second general election fairly shortly. But in the meantime there was a good deal of uncertainty nationally and if I were to pursue my political career further I needed to set about finding a winnable seat. But I felt morally bound to fight the Dartford constituency again. It would be wrong to leave them to find another candidate at such short notice. Moreover, it was difficult to imagine that I would be able to make the kind of impact in a second campaign that I had in the one just concluded. I was also extremely tired and, though no one with political blood in their veins shies away from the excitement of electioneering, another campaign within a short while was not an attractive prospect.

I had also decided to move to London. I had found a very small flat in St George’s Square Mews, in Pimlico. Mr Soward (Senior) came down from Dartford to help me decorate it. I was able to see a good deal more of Denis and in more relaxing conditions than in the hubbub of Conservative activism in Dartford.

I also learned to drive and acquired my first car. My sister, Muriel, had a pre-war Ford Prefect which my father had bought her for £129, and I now inherited it. My Ford Prefect became well known around Dartford, where I was re-adopted, and did me excellent service until I sold it for about the same sum when I got married.

The general election came in October 1951. This time I shaved another 1,000 votes off Norman Dodds’s majority and was hugely delighted to discover when all the results were in that the Conservatives now had an overall majority of seventeen.

During my time at Dartford I had continued to widen my acquaintanceship with senior figures in the Party. I had spoken as proposer of a vote of thanks to Anthony Eden (whom I had first met in Oxford) when he addressed a large and enthusiastic rally at Dartford football ground in 1949. The following year I spoke as seconder of a motion applauding the leadership of Churchill and Eden at a rally of Conservative Women at the Albert Hall, to which Churchill himself replied in vintage form. This was a great occasion for me – to meet in the flesh and talk to the leader whose words had so inspired me as I sat with my family around our wireless in Grantham. In 1950 I was appointed as representative of the Conservative Graduates to the Conservative Party’s National Union Executive, which gave me my first insight into Party organization at the national level.

The greatest social events in my diary were the Eve of (parliamentary) Session parties held by Sir Alfred Bossom, the Member for Maidstone, at his magnificent house, No. 5 Carlton Gardens.

Several marquees were put up, brilliantly lit and comfortably heated, in which the greatest and the not so great – like one Margaret Roberts – would mingle convivially. Sir Alfred Bossom would cheerily describe himself as the day’s successor to Lady Londonderry, the great Conservative hostess of the inter-war years. You would hardly have guessed that behind his amiable and easygoing exterior was a genius who had devised the revolutionary designs of some of the first skyscrapers in New York. He was specially kind and generous to me. It was his house from which I was married, and there that our reception was held; and it was he who proposed the toast to our happiness.

I was married on a cold and foggy December day at Wesley’s Chapel, City Road. It was more convenient for all concerned that the ceremony take place in London, but it was the Methodist minister from Grantham, our old friend the Rev. Skinner, who assisted the Rev. Spivey, the minister at City Road. Then all our friends – from Grantham, Dartford, Erith and London – came back to Sir Alfred Bossom’s. Finally, Denis swept me off to our honeymoon in Madeira, where I quickly recovered from the bone-shaking experience of my first and last aquatic landing in a seaplane to begin my married life against the background of that lovely island.

On our return from Madeira I moved into Denis’s flat in Swan Court, Flood Street in Chelsea. It was a light, sixth-floor flat with a fine view of London. It was also the first time I learned the convenience of living all on one level. As I would find again in the flat at 10 Downing Street, this makes life far easier to run. There was plenty of space – a large room which served as a sitting room and dining room, two good-sized bedrooms, another room which Denis used as a study and so on. Denis drove off to Erith every morning and would come back quite late in the evening. We quickly made friends with our neighbours; one advantage of living in a block of flats with a lift is that you meet everyone.

People felt that after all the sacrifices of the previous twenty years, they wanted to enjoy themselves, to get a little fun out of life. Although I may have been perhaps rather more serious than my contemporaries, Denis and I enjoyed ourselves quite as much as most, and more than some. We went to the theatre, we took holidays in Rome and Paris (albeit in very modest hotels), we gave parties and went to them, we had a wonderful time.

But the high point of our lives at that time was the coronation of Queen Elizabeth in June 1953. Those who had televisions – we did not – held house parties to which all their friends came to watch the great occasion. Denis and I, passionate devotees of the monarchy that we were, decided the occasion merited the extravagance of a seat in the covered stand erected in Parliament Square just opposite the entrance to Westminster Abbey. The tickets were an even wiser investment than Denis knew when he bought them, for it poured all day and most people in the audience were drenched – not to speak of those in the open carriages of the great procession. The Queen of Tonga never wore that dress again. Mine lived to see another day.

Pleasant though married life was in London, I still had time enough after housework to pursue a long-standing intellectual interest in the law. As with my fascination with politics, it was my father who had been responsible for stimulating this interest. Although he was not a magistrate, as Mayor of Grantham in 1945–46 my father would automatically sit on the Bench. During my university vacations I would go along with him to the Quarter Sessions (where many minor criminal offences were tried), at which an experienced lawyer would be in the chair as Recorder. On one such occasion my father and I lunched with him, a King’s Counsel called Norman Winning. I was captivated by what I saw in court, but I was enthralled by Norman Winning’s conversation about the theory and practice of law. At one point I blurted out: ‘I wish I could be a lawyer; but all I know about is chemistry and I can’t change what I’m reading at Oxford now.’ But Norman Winning said that he himself had read physics for his first degree at Cambridge before changing to law as a second degree. I objected that there was no way I could afford to stay on all those extra years at university. He replied that there was another way, perfectly possible but very hard work, which was to get a job in or near London, join one of the Inns of Court and study for my law exams in the evenings. And this in 1950 is precisely what I had done. Now with Denis’s support I could afford to concentrate on legal studies without taking up new employment. There was a great deal to read, and I also attended courses at the Council of Legal Education.

I had decided that what with running a home and reading for the Bar I would have to put my political ambitions on ice for some time to come. At twenty-six I could afford to do that and I told Conservative Central Office that such was my intention. But as a young woman candidate I still attracted occasional public attention. For example, in February 1952 an article of mine appeared in the Sunday Graphic on the position of women ‘At the Dawn of the New Elizabethan Era’. I was also on the list of sought-after Party speakers and was invited to constituencies up and down the country. In any case, try as I would, my fascination for politics got the better of all contrary resolutions.

I talked it over with Denis and he said that he would support me all the way. So in June I went to see Beryl Cook at Central Office and told her: ‘It’s no use. I must face it. I don’t like being left out of the political stream.’ As I knew she would, ‘Auntie Beryl’ gave me her full support and referred me to John Hare, the Party Vice-Chairman for Candidates. In the kindest possible way, he told me about the pressures which membership of the House of Commons placed on family life, but I said that Denis and I had talked it through and this was something we were prepared to face. I said that I would like to have the chance of fighting a marginal or safe seat next time round. We both agreed that, given my other commitments, this should be in London itself or within a radius of thirty miles. I promptly asked to be considered for Canterbury, which was due to select a candidate. I left Central Office very pleased with the outcome – though I did not get Canterbury.

The question which John Hare had raised with me about how I would combine my home life with politics was soon to become even more sensitive. For in August 1953 the twins, Mark and Carol, put in an appearance. Late one Thursday night, some six weeks before what we still called ‘the baby’ was due, I began to have pains. I had seen the doctor that day and he asked me to come back on the Monday for an X-ray because there was something he wanted to check. Now Monday seemed a very long way away, and off I was immediately taken to hospital. I was given a sedative which helped me sleep through the night. Then on Friday morning the X-ray was taken and to the great surprise of all it was discovered that I was to be the mother of twins. Unfortunately, that was not the whole story. The situation required a Caesarean operation the following day. The two tiny babies – a boy and a girl – had to wait a little before they saw their father. For Denis, imagining that all was progressing smoothly, had very sensibly gone to the Oval to watch the Test Match and it proved quite impossible to contact him. On that day he received two pieces of good but equally surprising news. England won the Ashes, and he found himself the proud father of twins.

I had to stay in hospital for over a fortnight: this meant that after the first few uncomfortable days of recovery I found myself with time on my hands. The first and most immediate task was to telephone all the relevant stores to order two rather than just one of everything. Oddly enough, the very depth of the relief and happiness at having brought Mark and Carol into the world made me uneasy. The pull of a mother towards her children is perhaps the strongest and most instinctive emotion we have. I was never one of those people who regarded being ‘just’ a mother or indeed ‘just’ a housewife as second best. Indeed, whenever I heard such implicit assumptions made both before and after I became Prime Minister it would make me very angry indeed. Of course, to be a mother and a housewife is a vocation of a very high kind. But I simply felt that it was not the whole of my vocation. I knew that I also wanted a career. A phrase that Irene Ward, MP for Tynemouth, and I often used was that ‘while the home must always be the centre of one’s life, it should not be the boundary of one’s ambitions’. Indeed, I needed a career because, quite simply, that was the sort of person I was. And not just any career. I wanted one which would keep me mentally active and prepare me for the political future for which I believed I was well suited.

So it was that at the end of my first week in hospital I came to a decision. I had the application form for my Bar finals in December sent to me. I filled it in and sent off the money for the exam, knowing that this little psychological trick I was playing on myself would ensure that I plunged into legal studies on my return to Swan Court with the twins, and that I would have to organize our lives so as to allow me to be both a mother and a professional woman.

This was not as difficult as it might sound. The flat was large enough, though being on the sixth floor, we had to have bars put on all the windows. And without a garden, the twins had to be taken out twice a day to Ranelagh Gardens. But this turned out to be good for them because they became used to meeting and playing with other children – though early on, when we did not know the rules, we had our ball confiscated by the Park Superintendent. Usually, however, it was the nanny, Barbara, who took Mark and Carol to the park, except at weekends when I took over. Barbara turned out to be a marvellous friend to the children.

Not long after I had the twins, John Hare wrote to me from Central Office:

I was delighted to hear that you had had twins. How very clever of you. How is this going to affect your position as a candidate? I have gaily been putting your name forward; if you would like me to desist, please say so.

I replied thanking him and noting:

Having unexpectedly produced twins – we had no idea there were two of them until the day they were born – I think I had better not consider a candidature for at least six months. The household needs considerable reorganization and a reliable nurse must be found before I can feel free to pursue such other activities with the necessary fervour.

So my name was, as John Hare put it, kept ‘in cold storage for the time being’. It was incumbent on me to say when I would like to come onto the active list of candidates again.

My self-prescribed six months of political limbo were quickly over. I duly passed my Bar finals. I had begun by considering specializing in patent law but it seemed that the opportunities there were very limited and so perhaps tax law would be a better bet. In any case, I would need a foundation in the criminal law first. So in December 1953 I joined Frederick Lawton’s Chambers in the Inner Temple for a six months’ pupillage. Fred Lawton’s was a common law Chambers. He was, indeed, one of the most brilliant criminal lawyers I ever knew. He was witty, with no illusions about human nature or his own profession, extraordinarily lucid in exposition, and a kind guide to me.

In fact, I was to go through no fewer than four sets of Chambers, partly because I had to gain a grounding in several fields before I was competent to specialize in tax. So I witnessed the rhetorical fireworks of the Criminal Bar, admired the precise draftsmanship of the Chancery Bar and then delved into the details of company law. But I became increasingly confident that tax law could be my forte. It was a meeting point with my interest in politics; it offered the right mixture of theory and practical substance; and of one thing we could all be sure – there would never be a shortage of clients desperate to cut their way out of the jungle of over-complex and constantly changing tax law.

Studying, observing, discussing and eventually practising law had a profound effect on my political outlook. In this I was probably unusual. Familiarity with the law usually breeds if not contempt, at least a large measure of cynicism. For me, however, it gave a richer significance to that expression ‘the rule of law’ which so easily tripped off the Conservative tongue.