По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

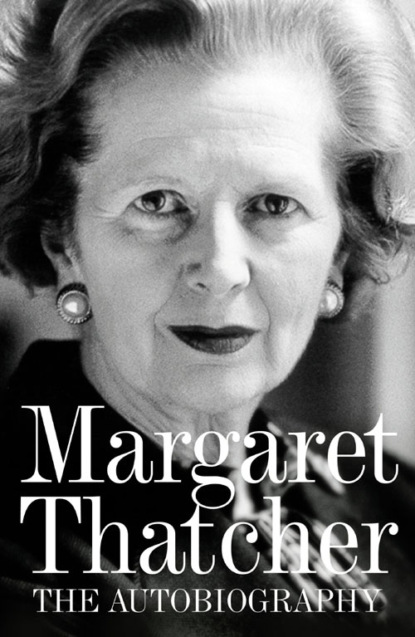

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Yet, behind the official propaganda, the grey streets, all but empty shops and badly maintained workers’ housing blocks, Russian humanity peeped out. There was no doubt about the genuineness of the tears when the older people at Leningrad and Stalingrad told me about their terrible sufferings in the war. The young people I talked to from Moscow University, though extremely cautious about what they said in the full knowledge that they were under KGB scrutiny, were clearly fascinated to learn all they could about the West. And even bureaucracy can prove human. When I visited the manager of the Moscow passenger transport system he explained to me at great length how decisions about new development had to go from committee to committee in what seemed – as I said – an endless chain of non-decision-making. I caught the eye of a young man, perhaps the chairman’s assistant, standing behind him and he could not repress a broad smile.

On my return to London I was moved to the Education portfolio in the Shadow Cabinet. Edward Boyle was leaving politics to become Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leeds. There was by now a good deal of grassroots opposition at Party Conferences to what was seen as his weakness in defence of the grammar schools. Although our views had diverged, I was sorry to see him go and I would miss his intellect, sensitivity and integrity. But for me this was definitely a promotion, even though, as I have since learned, I was in fact the reserve candidate, after Keith Joseph: I got the job because Reggie Maudling refused to take over Keith’s job as Trade and Industry Shadow.

I was delighted with my new role. I had risen to my present position as a result of free (or nearly free) good education, and I wanted others to have the same chance. Socialist education policies, by equalizing downwards and denying gifted children the opportunity to get on, were a major obstacle to that. I was also fascinated by the scientific side – the portfolio in those days being to shadow the Department of Education and Science.

Education was by now one of the main battlegrounds of politics. Since their election in 1964 Labour had been increasingly committed to making the whole secondary school system comprehensive, and had introduced a series of measures, to make local education authorities (LEAs) submit plans for such a change. (The process culminated in legislation, introduced a few months after I took over as Education Shadow.) The difficulties Edward had faced in formulating and explaining our response soon became clear to me.

The Shadow Cabinet and the Conservative Party were deeply split over the principle of selection in secondary education and, in particular, over the examination by which children were selected at the age of eleven, the 11-Plus. To oversimplify a little: first, there were those who had no real interest in state education because they themselves and their children went to private schools. This was a group all too likely to be swayed by arguments of political expediency. Second, there were those who, themselves or their children, had failed to get into grammar school and had been disappointed with the education received at a secondary modern. Third, there were those Conservatives who had absorbed a large dose of the fashionable egalitarian doctrines of the day. Finally, there were people like me who had been to good grammar schools, were strongly opposed to their destruction and felt no inhibitions at all about arguing for the 11-Plus.

But by the time I took on the Education portfolio, the Party’s policy group had presented its report and the policy itself was largely established. It had two main aspects. We had decided to concentrate on improving primary schools. And in order to defuse as much as possible the debate about the 11-Plus, we stressed the autonomy of local education authorities in proposing the retention of grammar schools or the introduction of comprehensive schools.

The good arguments for this programme were that improvements in the education of younger children were vital if the growing tendency towards illiteracy and innumeracy was to be checked and, secondly, that in practice the best way to retain grammar schools was to fight centralization. There were, however, arguments on the other side. There was not much point in spending large sums on nursery and primary schools and the teachers for them, if the teaching methods and attitudes were wrong. Nor, of course, were we in the long run going to be able to defend grammar schools – or, for that matter, private schools, direct grant schools and even streamed comprehensive schools – if we did not fight on grounds of principle.

Within the limits which the agreed policy and political realities allowed me, I went as far as I could. This was a good deal too far for some people, as I learned when, shortly after my appointment, I was the guest of the education correspondents at the Cumberland Hotel in London. I put the case not just for grammar schools but for secondary moderns. Those children who were not able to shine academically could in fact acquire responsibilities and respect at a separate secondary modern school, which they would never have done if in direct and continual competition and contact with the more academically gifted. I was perfectly prepared to see the 11-Plus replaced or modified by testing later in a child’s career, if that was what people wanted. I knew that it was quite possible for late developers at a secondary modern to be moved to the local grammar school so that their abilities could be properly stretched. I was sure that there were too many secondary modern schools which were providing a second-rate education – but this was something which should be remedied by bringing their standards up, rather than grammar school standards down. Only two of those present at the Cumberland Hotel lunch seemed to agree. Otherwise I was met by a mixture of hostility and blank incomprehension. It opened my eyes to the dominance of socialist thinking among those whose task it was to provide the public with information about education.

There were still some relatively less important issues in Conservative education policy to be decided. I fought hard to have an unqualified commitment to raising the school leaving age to sixteen inserted into the manifesto, and succeeded against some doubts from the Treasury team. I also met strong opposition from Ted Heath when, at our discussions at Selsdon Park in early 1970, I argued that the manifesto should endorse the proposed new independent University of Buckingham. I lost this battle but was at least finally permitted to make reference to the university in a speech. Quite why Ted felt so passionately against it I have never fully understood.

The Selsdon Park policy weekend at the end of January and beginning of February was a success, but not for the reasons usually given. The idea that Selsdon Park was the scene of debate which resulted in a radical rightward shift in Party policy is false. The main lines of policy had already been agreed and incorporated into a draft manifesto which we spent our time considering in detail. Our line on immigration had also been carefully spelt out. Our proposals for trade union reform had been published in Fair Deal at Work. On incomes policy, a rightward but somewhat confused shift was in the process of occurring. Labour had effectively abandoned its own policy. There was no need, therefore, to enter into the vexed question of whether some kind of ‘voluntary’ incomes policy might be pursued. But it was clear that Reggie Maudling was unhappy that we had no proposals to deal with what was still perceived as ‘wage inflation’. In fact, the manifesto, in a judicious muddle, avoided either a monetarist approach or a Keynesian one and said simply: ‘The main causes of rising prices are Labour’s damaging policies of high taxation and devaluation. Labour’s compulsory wage control was a failure and we will not repeat it.’

This led us into some trouble later. During the election campaign the fallacious assertion that high taxes caused inflation inspired a briefing note from Central Office. This note allowed the Labour Party to claim subsequently that we had said that we would cut prices ‘at a stroke’ by means of tax cuts.

Thanks to the blanket press coverage of Selsdon Park, we seemed to be a serious alternative Government committed to long-term thinking about the policies for Britain’s future. We were also helped by Harold Wilson’s attack on ‘Selsdon Man’. It gave us an air of down-to-earth right-wing populism which countered the somewhat aloof image conveyed by Ted. Above all, both Selsdon Park and the Conservative manifesto, A Better Tomorrow, contrasted favourably with the deviousness, inconsistency and horse trading which by now characterized the Wilson Government, especially since the abandonment of In Place of Strife under trade union pressure.* (#ulink_44f513fb-eab1-5106-a527-93cb86603e27)

Between our departure from Selsdon Park and the opening of the general election campaign in May, however, there was a reversal of the opinion poll standing of the two parties. Quite why this turnaround had occurred (or indeed how real it actually was) is hard to know. With the prospect of a general election there is always a tendency for disillusioned supporters to resume their party allegiance. But it is also true – and it is something that we would pay dearly for in government – that we had not seriously set out to win the battle of ideas against socialism during our years in Opposition. And indeed, our rethinking of policy had not been as fundamental as it should have been.

The campaign itself was largely taken up with Labour attacks on our policies. We for our part, like any Opposition, highlighted the long list of Labour’s broken promises – ‘steady industrial growth all the time’, ‘no stop-go measures’, ‘no increase in taxation’, ‘no increase in unemployment’, ‘the pound in your pocket not devalued’, ‘economic miracle’ and many more. This was the theme I pursued in my campaign speeches. But I also used a speech to a dinner organized by the National Association of Head Teachers in Scarborough to outline our education policies.

It is hard to know just what turned the tide. Paradoxically perhaps, the Conservative figures who made the greatest contribution were those two fierce enemies, Ted Heath and Enoch Powell. No one could describe Ted as a great communicator, but as the days went by he came across as a decent man, someone with integrity and a vision – albeit a somewhat technocratic one – of what he wanted for Britain. It seemed, to use Keith’s words to me five years earlier, that he had ‘a passion to get Britain right’. This was emphasized in Ted’s powerful introduction to the manifesto in which he attacked Labour’s ‘cheap and trivial style of government’ and ‘government by gimmick’ and promised ‘a new style of government’. Ted’s final Party Election Broadcast also showed him as an honest patriot who cared deeply about his country and wanted to serve it. He had fought a good campaign. For his part, Enoch Powell made three powerful speeches on the failures of the Labour Government, urging people to vote Conservative. There is some statistical evidence that Enoch’s intervention helped tip the balance in the West Midlands.

My own result was announced to a tremendous cheer at Hendon College of Technology – I had increased my majority to over 11,000 over Labour. Then I went down to the Daily Telegraph party at the Savoy, where it quite soon became clear that the opinion polls had been proved wrong and that we were on course for an overall majority.

Friday was spent in my constituency clearing up and writing the usual thank-you letters. I thought that probably Ted would have at least one woman in his Cabinet, and that since he had got used to me in the Shadow Cabinet I would be the lucky girl. On the same logic, I would probably get the Education brief.

On Saturday morning the call from the No. 10 Private Secretary came through. Ted wanted to see me. When I went in to the Cabinet Room I began by congratulating him on his victory. But not much time was spent on pleasantries. He was as ever brusque and businesslike, and he offered me the job of Education Secretary, which I accepted.

I went back to the flat at Westminster Gardens with Denis and we drove to Lamberhurst.* (#ulink_b05bfba2-3708-5ce2-874a-05bff52e7973)

Sadly my father was not alive to share the moment. Shortly before his death in February, I had gone up to Grantham to see him. My stepmother, Cissy, whom he had married several years earlier and with whom he had been very happy, was constantly at his bedside. While I was there, friends from the church, business, local politics, the Rotary and bowling club, kept dropping in ‘just to see how Alf was’. I hoped that at the end of my life I too would have so many good friends.

I understand that my father had been listening to me as a member of a panel on a radio programme just before he died. He never knew that I would become a Cabinet minister, and I am sure that he never imagined I would eventually become Prime Minister. He would have wanted these things for me because politics was so much a part of his life and because I was so much his daughter. But nor would he have considered that political power was the most important or even the most effective thing in life. In searching through my papers to assemble the material for this volume I came across some of my father’s loose sermon notes slipped into the back of my sixth-form chemistry exercise book.

Men, nations, races or any particular generation cannot be saved by ordinances, power, legislation. We worry about all this, and our faith becomes weak and faltering. But all these things are as old as the human race – all these things confronted Jesus 2,000 years ago … This is why Jesus had to come.

My father lived these convictions to the end.

* (#ulink_1f8dacb8-68b7-520c-820f-30b4e4cc346a)A Balance of Power (1986), p.42.

* (#ulink_01e31219-cb2d-5a54-8c36-737ded741931)In Place of Strife was the – in retrospect ironically chosen – title of a Labour White Paper of 1969 which proposed a range of union reforms. The proposals had to be abandoned due to internal opposition within the Cabinet and the Labour Party, led by Jim Callaghan.

* (#ulink_97bc4522-6265-51bb-9719-5ee870320742) We had bought ‘The Mount’, a mock-Tudor house with a large garden in Lamberhurst, near Tunbridge Wells, in 1965. In 1972 we sold it, and bought the house in Flood Street (Chelsea) which would be my home until in 1979 I moved into 10 Downing Street.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_317ee1b3-d7e5-5079-b740-ec348ddb851e)

Teacher’s Pest (#ulink_317ee1b3-d7e5-5079-b740-ec348ddb851e)

The Department of Education 1970–1974

ON MONDAY 22 JUNE 1970 I arrived at the Department of Education and Science (DES) in its splendid old quarters in Curzon Street. I was met by the Permanent Secretary, Bill (later Sir William) Pile and the outgoing Permanent Secretary, Sir Herbert Andrew. They gave me a warm greeting and showed me up to my impressive office. It was all too easy to slip into the warm water of civil service respect for ‘the minister’, but I was very conscious that hard work lay ahead. I was generally satisfied with the ministerial team I had been allotted: one friendly, one hostile and one neutral. My old friend Lord Eccles, as Paymaster-General, was responsible for the Arts. Bill Van Straubenzee, a close friend of Ted’s, dealt with Higher Education. Lord Belstead answered for the department in the Lords. I was particularly pleased that David Eccles, a former Minister of Education, was available, though installed in a separate building, to give me private advice based on his knowledge of the department.

My difficulties with the department, however, were not essentially about personalities. Nor did they stem from the opposition between my own executive style of decision-making and the more consultative style to which they were accustomed. Indeed, by the time I left I was aware that I had won a somewhat grudging respect because I knew my own mind and expected my decisions to be carried out promptly and efficiently. The real problem was – in the widest sense – one of politics.

The ethos of the DES was self-righteously socialist. For the most part, these were people who retained an almost reflex belief in the ability of central planners and social theorists to create a better world. There was nothing cynical about this. Years after many people in the Labour Party had begun to have their doubts, the educationalists retained a sense of mission. Equality in education was not only the overriding good, irrespective of the practical effects of egalitarian policies on particular schools; it was a stepping stone to achieving equality in society, which was itself an unquestioned good. It was soon clear to me that on the whole I was not among friends.

My difficulties with the civil service were compounded by the fact that we had been elected in 1970 with a set of education policies which were perhaps less clear than they appeared. During the campaign I had hammered away at seven points:

a shift of emphasis onto primary schools

the expansion of nursery education (which fitted in with Keith Joseph’s theme of arresting the ‘cycle of deprivation’)

in secondary education, the right of local education authorities to decide what was best for their areas, while warning against making ‘irrevocable changes to any good school unless … the alternative is better’

raising the school leaving age to sixteen

encouraging direct grant schools and retaining private schools* (#ulink_ee5ff0af-6086-584c-8ed5-d1c9d2375a7b)

expanding higher and further education

holding an inquiry into teacher training

But those pledges did not reflect a clear philosophy. Different people and different groups within the Conservative Party favoured very different approaches to education, in particular to secondary education and the grammar schools. On the one hand, there were some Tories who had a commitment to comprehensive education which barely distinguished them from moderate socialists. On the other, the authors of the so-called Black Papers on education had started to spell out a radically different approach, based on discipline, choice and standards (including the retention of existing grammar schools with high standards).

On that first day at the department I brought with me a list of about fifteen points for action which I had written down over the weekend in an old exercise book. After enlarging upon them, I tore out the pages and gave them to Bill Pile. The most immediate action point was the withdrawal of Tony Crosland’s Circular 10/65, under which local authorities were required to submit plans for reorganizing secondary education on completely comprehensive lines, and Circular 10/66, issued the following year, which withheld capital funding from local education authorities that refused to go comprehensive.

The department must have known that this was in our manifesto – but apparently they thought that the policy could be watered down, or its implementation postponed. I, for my part, knew that the pledge to stop pressuring local authorities to go comprehensive was of great importance to our supporters, and that it was important to act speedily in order to end uncertainty. Consequently, even before I had given Bill Pile my fifteen points, I had told the press that I would immediately withdraw Labour’s Circulars. I even indicated that this would have happened by the time of the Queen’s Speech. The alarm this provoked seems to have made its way to No. 10, for I was reminded that I should have Cabinet’s agreement to the policy, though of course this was only a formality.

More seriously, I had not understood that the withdrawal of one Circular requires the issue of another. My civil servants made no secret of the fact that they considered that a Circular should contain a good deal of material setting out the department’s views on its preferred shape for secondary education in the country as a whole. This might take for ever, and in any event I did not see things that way. The essence of our policy was to encourage variety and choice rather than ‘plan’ the system. Moreover, to the extent that it was necessary to lay down from the centre the criteria by which local authorities’ reorganization proposals would be judged, this could be done now in general terms, with any further elaboration taking place later. It was immensely difficult to persuade them that I was serious. I eventually succeeded by doing an initial draft myself: they quickly decided that co-operation was the better part of valour. And in the end a very short Circular – Circular 10/70 – was issued on Tuesday 30 June: in good time for the Education Debate on the Queen’s Speech on Wednesday 8 July.

I now came under fierce attack from the educational establishment because I had failed to engage in the ‘normal consultation’ which took place before a Circular was issued. I felt no need to apologize. As I put it in my speech in the House, we had after all ‘just completed the biggest consultation of all’, that is, a general election. But this carried little weight with those who had spent the last twenty-five years convinced that they knew best. Ted Short, Labour’s Education spokesman, a former schoolmaster, even went so far as to suggest that, in protest, teachers should refuse to mark 11-Plus exam papers. A delegation from the NUT came to see me to complain about what I had done. Significantly, the brunt of their criticism was that I had ‘resigned responsibility for giving shape to education’. If indeed that had been my responsibility, I do not think the NUT would have liked the shape I would have given it.

In fact, the policy which I now pursued was more nuanced than the caricatures it attracted – though a good deal could have been said for the positions caricatured. Circular 10/70 withdrew the relevant Labour Government Circulars and then went on: ‘The Secretary of State will expect educational considerations in general, local needs and wishes in particular and the wise use of resources to be the main principles determining the local pattern.’ It also made it clear that the presumption was basically against upheaval: ‘where a particular pattern of organization is working well and commands general support the Secretary of State does not wish to cause further change without good reason’.

Strange though it may seem, although local education authorities had been used to sending in general plans for reorganization of all the schools under their control, neither these nor the Secretary of State’s comments on them had any legal standing. The law only entered the picture when the notices were issued under Section 13 of the 1944 Education Act. This required local education authorities to give public notice – and notice to the department – of their intention to close or open a school, significantly alter its character, or change the age range of its pupils. Locally, this gave concerned parents, school governors and residents two months in which to object. Nationally, it gave me, as Secretary of State, the opportunity to intervene. It read: ‘Any proposals submitted to the Secretary of State under this section may be approved by him after making such modifications therein, if any, as appear to him desirable.’

The use of these powers to protect particular good schools against sweeping reorganization was not only a departure from Labour policy; it was also a conscious departure from the line taken by Edward Boyle, who had described Section 13 as ‘reserve powers’. But as a lawyer myself and as someone who believed that decisions about changing and closing schools should be sensitive to local opinion, I thought it best to base my policy on the Section 13 powers rather than on exhortation through Circulars. I was very conscious that my actions were subject to the scrutiny of the courts and that the grounds on which I could intervene were limited. And by the time I made my speech in the debate I was in a position to spell out more clearly how this general approach would be implemented.

My policy had a further advantage. At a time when even Conservative education authorities were bitten with the bug of comprehensivization, it offered the best chance of saving good local grammar schools. The administrative disadvantage was that close scrutiny of large numbers of individual proposals meant delays in giving the department’s response. Inevitably, I was attacked on the grounds that I was holding back in order to defer the closure of more grammar schools. But in this the critics were unjust. I took a close interest in speeding up the responses. It was just that we were deluged.

For all the political noise which arose from this change of policy, its practical effects were limited. During the whole of my time as Education Secretary we considered some 3,600 proposals for reorganization – the great majority of them proposals for comprehensivization – of which I rejected only 325, or about 9 per cent. In the summer of 1970 it had seemed possible that many more authorities might decide to reverse or halt their plans. For example, Conservative-controlled Birmingham was one of the first education authorities to welcome Circular 10/70. A bitter fight had been carried on to save the city’s thirty-six grammar schools. But in 1972 Labour took control and put forward its own plans for comprehensivization. I rejected sixty of the council’s 112 proposals in June 1973, saving eighteen of the city’s grammar schools.