По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

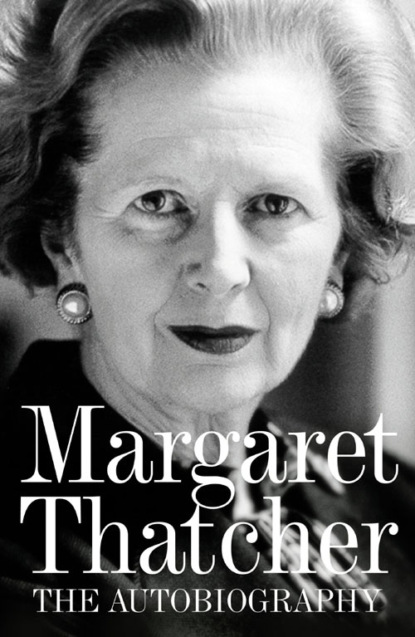

Margaret Thatcher: The Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I felt victory – almost tangibly – slip away from us in the last week. I just could not believe it when I heard on the radio of the leak of evidence taken by the Pay Board which purported to show that the miners could have been paid more within Stage 3, with the implication that the whole general election was unnecessary. The Government’s attempts to deny this – and there did indeed turn out to have been a miscalculation – were stumbling and failed to carry conviction. From now on it was relentlessly downhill.

Two days later, Enoch Powell urged people to vote Labour in order to secure a referendum on the Common Market. I could understand the logic of his position, which was that membership of the Common Market had abrogated British sovereignty and that the supreme issue in politics was therefore how to restore it. But what shocked me was his manner of doing it – announcing only on the day the election was called that he would not be contesting his Wolverhampton seat and then dropping this bombshell at the end of the campaign. It seemed to me that to betray one’s local supporters and constituency workers in this way was heartless. I suspect that Enoch’s decision had a crucial effect.

Then three days later there was another blow. Campbell Adamson, the Director-General of the CBI, publicly called for the repeal of the Industrial Relations Act. It was all too typical of the way in which Britain’s industrial leaders were full of bravado before battle was joined, but lacked the stomach for a fight.

By polling day my optimism had been replaced by unease.

That sentiment grew as I heard from Finchley and elsewhere around the country of a surprisingly heavy turn-out of voters to the polls that morning. I would have liked to think that these were all angry Conservatives, coming out to demonstrate their refusal to be blackmailed by trade union power. But it seemed more likely that they were voters from the Labour-dominated council estates who had come out to teach the Tories a lesson.

The results quickly showed that we had nothing to be cheerful about. We lost thirty-three seats. It would be a hung Parliament. Labour had become the largest party with 301 seats – seventeen short of a majority; we were down to 296, though with a slightly higher percentage of the vote than Labour; the Liberals had gained almost 20 per cent of the vote with fourteen seats, and smaller parties, including the Ulster Unionists, held twenty-three. My own majority in Finchley was down from 11,000 to 6,000, though some of that decline was the result of boundary changes in the constituency.

On Friday afternoon we met, a tired and downcast fag-end of a Cabinet, to be asked by Ted Heath for our reactions as to what should now be done. There were a number of options. Ted could advise the Queen to send for Harold Wilson as the leader of the largest single party. Or the Government could face Parliament and see whether it could command support for its programme. Or he could try to do a deal with the smaller parties for a programme designed to cope with the nation’s immediate difficulties. Having alienated the Ulster Unionists through our Northern Ireland policy, this in effect meant a deal with the Liberals – though even that would not have given us a majority. There was little doubt from the way Ted spoke that this was the course he favoured.

My own instinctive feeling was that the party with the largest number of seats in the House of Commons was justified in expecting that they would be called to try to form a government. But Ted argued that with the Conservatives having won the largest number of votes, he was duty bound to explore the possibility of coalition. So he offered the Liberal Leader Jeremy Thorpe a place in a coalition government and promised a Speaker’s conference on electoral reform. Thorpe went away to consult his party. Although I wanted to remain Secretary of State for Education, I did not want to do so at the expense of the Conservative Party’s never forming a majority government again. Yet that is what the introduction of proportional representation, which the Liberals would be demanding, might amount to. I was also conscious that this horse-trading was making us look ridiculous. The British dislike nothing more than a bad loser. It was time to go.

When we met again on Monday morning Ted gave us a full account of his discussions with the Liberals. They had not been willing to go along with what Jeremy Thorpe wanted. A formal reply from him was still awaited. But it now seemed almost certain that Ted would have to tender his resignation. The final Cabinet was held at 4.45 that afternoon. By now Jeremy Thorpe’s reply had been received. From what Ted said, there were clues that his mind was already turning to the idea of a National Government of all parties, something which would increasingly attract him. It did not, of course, attract me at all. In any case, the Liberals were not going to join a coalition government with us. There was nothing more to say.

I left Downing Street, sad but with some sense of relief. I had given little thought to the future. But I knew in my heart that it was time not just for a change in government but for a change in the Conservative Party.

* (#ulink_42459718-b2f8-5c32-aa22-657e424a31a0) ‘The Lesson’ (1902). The lesson in question was the Boer War, in which Britain had suffered many military reverses.

* (#ulink_a9134ceb-bdf7-5ddd-9027-d49927748216) A State of Emergency may be proclaimed by the Crown – effectively by ministers – whenever a situation arises which threatens to deprive the community of the essentials of life by disrupting the supply and distribution of food, water, fuel or light, or communications. It gives Government extensive powers to make regulations to restore these necessities. Troops may be used. If Parliament is not sitting when the proclamation is made, it must be recalled within five days. A State of Emergency expires at the end of one month, but may be extended.

* (#ulink_e71acd55-e56b-551d-b3ab-845c37bcb2af) John Poulson was an architect convicted in 1974 of making corrupt payments to win contracts. A number of local government figures also went to jail. Reggie Maudling had served on the board of one of Poulson’s companies.

* (#ulink_20937384-a3fb-5788-a411-baa08060252d)Hansard, 13 June 1972; Volume 838, columns 1319–20.

* (#ulink_4977dd8e-dafd-5863-9f00-3c86e9b4ff5c) Alan Walters became my economic adviser as Prime Minister 1981–84 and again in 1989.

* (#ulink_2100bdad-7baf-5a73-a9df-9b55d1aadd95) M1 comprised the total stock of money held in cash and in current and deposit accounts at a particular point in time; M3 included the whole of M1, with the addition of certain other types of bank accounts, including those held in currencies other than sterling.

CHAPTER EIGHT (#ulink_d535670f-5330-58d7-9706-a52618995dc9)

Seizing the Moment (#ulink_d535670f-5330-58d7-9706-a52618995dc9)

The October 1974 general election and the campaign for the Tory Leadership

IT IS NEVER EASY to go from government to opposition. But for several reasons it was particularly problematical for the Conservatives led by Ted Heath. First, of course, we had up until almost the last moment expected to win. Whatever the shortcomings of our Government’s economic strategy, every department had its own policy programme stretching well into the future. This now had to be abandoned for the rigours of Opposition. Secondly, Ted himself desperately wanted to continue as Prime Minister. He had been unceremoniously ejected from 10 Downing Street and for some months had to take refuge in the flat of his old friend and PPS Tim Kitson, having no home of his own – from which years later I drew the resolution that when my time came to depart I would at least have a house to go to. Ted’s passionate desire to return as Prime Minister lay behind much of the talk of coalitions and Governments of National Unity which came to disquiet the Party. The more that the Tory Party moved away from Ted’s own vision, the more he wanted to see it tamed by coalition. Thirdly, and worst of all perhaps, the poisoned legacy of our U-turns was that we had no firm principles, let alone much of a record, on which to base our arguments. And in Opposition argument is everything.

I was glad that Ted did not ask me to cover my old department at Education but gave me the Environment portfolio instead. I was convinced that both rates and housing – particularly the latter – were issues which had contributed to our defeat. The task of devising and presenting sound and popular policies in these areas appealed to me.

There were rumblings about Ted’s own position, though that is what they largely remained. This was partly because most of us expected an early general election to be called in order to give Labour a working majority, and it hardly seemed sensible to change leaders now. But there were other reasons. Ted still inspired nervousness, even fear among many of his colleagues. In a sense, even the U-turns contributed to the aura around him. For he had single-handedly reversed Conservative policies and had gone far, with his lieutenants, in reshaping the Conservative Party. Paradoxically too, both those committed to Ted’s approach and those – like Keith and me and many on the backbenches – who thought very differently agreed that the vote-buying policies which the Labour Party was now pursuing would inevitably lead to economic collapse. Just what the political consequences of that would be was uncertain. But there were many Tory wishful thinkers who thought that it might result in the Conservative Party somehow returning to power with a ‘doctor’s mandate’. And Ted had no doubt of his own medical credentials.

He did not, though, make the concessions to his critics in the Party which would have been required. He might have provided effectively against future threats to his position if he had changed his approach in a number of ways. He might have shown at least some willingness to admit and learn from the Government’s mistakes. He might have invited talented backbench critics to join him as Shadow spokesmen and contribute to the rethinking of policy. He might have changed the overall complexion of the Shadow Cabinet to make it more representative of parliamentary opinion.

But he did none of these things. He replaced Tony Barber – who announced that he intended to leave the Commons though he would stay on for the present in the Shadow Cabinet without portfolio – with Robert Carr, who was even more committed to the interventionist approach that had got us into so much trouble. He promoted to the Shadow Cabinet during the year those MPs like Michael Heseltine and Paul Channon who were seen as his acolytes, and were unrepresentative of backbench opinion of the time. Only John Davies and Joe Godber, neither of whom was ideologically distinct, were dropped. Above all, he set his face against any policy rethinking that would imply that his Government’s economic and industrial policy had been seriously flawed. When Keith Joseph was not made Shadow Chancellor, he said he wanted no portfolio but rather to concentrate on research for new policies – something which would prove as dangerous to Ted as it was fruitful for the Party. Otherwise, these were depressing signals of ‘more of the same’ when the electorate had clearly demonstrated a desire for something different. Added to this, the important Steering Committee of Shadow Ministers was formed even more in Ted’s image. I was not invited to join it, and of its members only Keith and perhaps Geoffrey Howe were likely to oppose Ted’s wishes.

Between the February and October 1974 elections most of my time was taken up with work on housing and the rates. I had an effective housing policy group of MPs working with me. Hugh Rossi, a friend and neighbouring MP, was a great housing expert, with experience of local government. Michael Latham and John Stanley were well versed in the building industry. The brilliant Nigel Lawson, newly elected, always had his own ideas. We also had the help of people from the building societies and construction industry. It was a lively group which I enjoyed chairing.

The political priority was clearly lower mortgage rates. The technical problem was how to achieve these without open-ended subsidy. In government we had introduced a mortgage subsidy, and there had been talk of taking powers to control the mortgage rate. The Labour Government quickly came up with its own scheme, devised by Harold Lever, to make large cheap short-term loans to the building societies. Our task was to devise something more attractive.

As well as having an eye for a politically attractive policy, I had always believed in a property-owning democracy and wider home ownership. It is cheaper to assist people to buy homes with a mortgage – whether by a subsidized mortgage rate, or by help with the deposit, or just by mortgage interest tax relief – than it is to build more council houses or to buy up private houses through municipalization. I used to quote the results of a Housing Research Foundation study which observed: ‘On average each new council house now costs roughly £900 a year in subsidy in taxes and rates (including the subsidy from very old council houses) … Tax relief on an ordinary mortgage, if this be regarded as a subsidy, averages about £280 a year.’ My housing policy group met regularly on Mondays. Housing experts and representatives from the building societies gave their advice. It was clear to me that Ted and others were determined to make our proposals on housing and possibly rates the centrepiece of the next election campaign, which we expected sooner rather than later. For example, at the Shadow Cabinet on Friday 3 May we had an all-day discussion of policies for the manifesto. I reported on housing and was authorized to set up a rates policy group. But this meeting was more significant for another reason. At it Keith Joseph argued at length but in vain for a broadly ‘monetarist’ approach to dealing with inflation.

The question of the rates was a far more difficult one than any aspect of housing policy, and I had a slightly different group to help me. Reform, let alone abolition, of the rates had profound implications for the relations between central and local government and for the different local authority services, particularly education. I drew on the advice of the experts – municipal treasurers proved the best source, and gave readily of their technical advice. But working as I was under tight pressure of time and close scrutiny by Ted and others who expected me to deliver something radical, popular and defensible, my task was not an easy one.

The housing policy group had already held its seventh meeting and our proposals were well developed by the time the rates group started work on 10 June. I knew Ted and his advisers wanted a firm promise that we would abolish the rates. But I was loath to make such a pledge until we were clear about what to put in their place. Anyway, if there was to be an autumn election, there was little chance of doing more than finding a sustainable line to take in the manifesto.

Meanwhile, throughout that summer of 1974 I received far more publicity than I had ever previously experienced. Some of this was inadvertent. The interim report of the housing policy group which I circulated to Shadow Cabinet appeared on the front page of The Times on Monday 24 June. On the previous Friday Shadow Cabinet had spent the morning discussing the fourth draft of the manifesto. By now the main lines of my proposed housing policy were agreed. The mortgage rate would be held down to some unspecified level by cutting the composite rate of tax paid by building societies on depositors’ accounts, in other words by subsidy disguised as tax relief. A grant would be given to firsttime buyers saving for a deposit, though again no figure was specified. There would be a high-powered inquiry into building societies; this was an idea I modelled on my earlier James Inquiry into teachers’ training. I hoped it might produce a long-term answer to the problem of high mortgage rates and yet save us from an open-ended subsidy.

The final point related to the right of tenants to buy their council houses. Of all our proposals this was to prove the most far-reaching and the most popular. The February 1974 manifesto had offered council tenants the chance to buy their houses, but retained a right of appeal for the council against sale, and had not offered a discount. We all wanted to go further than this; the question was how far. Peter Walker constantly pressed for the ‘Right to Buy’ to be extended to council tenants at the lowest possible prices. My instinct was on the side of caution. It was not that I underrated the benefits of wider property ownership. Rather, I was wary of alienating the already hard-pressed families who had scrimped to buy a house on one of the new private estates at the market price and who had seen the mortgage rate rise and the value of their house fall. These people were the bedrock Conservative voters for whom I felt a natural sympathy. They would, I feared, strongly object to council house tenants who had made none of their sacrifices suddenly receiving what was in effect a large capital sum from the Government. We might end up losing more support than we gained. In retrospect, this argument seems both narrow and unimaginative. And it was. But there was a lot to be said politically for it in 1974 at a time when the value of people’s houses had slumped so catastrophically.

In the event, the October 1974 manifesto offered council tenants who had been in their homes for three years or more the right to buy them at a price a third below market value. If the tenant sold again within five years he would surrender part of any capital gain. Also, by the time the manifesto reached its final draft, we had quantified the help to be given to first-time buyers of private houses and flats. We would contribute £1 for every £2 saved for the deposit up to a given ceiling. (We ducked the question of rent decontrol.)

It was, however, the question of how low a maximum mortgage interest rate we would promise in the manifesto that caused me most trouble. When I was in the car on the way from London to Tonbridge on Wednesday 28 August in order to record a Party Political Broadcast the bleeper signalled that I must telephone urgently. Ted wanted a word. Willie Whitelaw answered the phone and it was clear that the two of them, and doubtless others of the inner circle, were meeting. Ted came on the line. He asked me to announce on the PPB the precise figure to which we would hold down mortgages, and to take it down as low as I could. I said I could understand the psychological point about going below 10 per cent. That need could be satisfied by a figure of 9½ per cent, and in all conscience I could not take it down any further. To do so would have a touch of rashness about it. I was already worried about the cost. I did not like this tendency to pull figures out of the air for immediate political impact without proper consideration of where they would lead. So I stuck at 9½ per cent.

It was a similar story on the rates. When we had discussed the subject at our Shadow Cabinet meeting on Friday 21 June I had tried to avoid any firm pledge. I suggested that our line should be one of reform to be established on an all-party basis through a Select Committee. Even more than housing, this was not an area in which precipitate pledges were sensible. Ted would have none of this and said I should think again.

In July Charles Bellairs at the Conservative Research Department and I worked on a draft rates section for the manifesto. We were still thinking in terms of an inquiry and an interim rate relief scheme. I went along to discuss our proposals at the Shadow Cabinet Steering Committee. I argued for the transfer of teachers’ salaries – the largest item of local spending – from local government onto the Exchequer. Another possibility I raised was the replacement of rates with a system of block grants, with local authorities retaining discretion over spending but within a total set by central government. Neither of these possibilities was particularly attractive. But at least discussion revealed to those present that ‘doing something’ about the rates was a very different matter from knowing what to do.

On Saturday 10 August I used my speech to the Candidates’ Conference at the St Stephen’s Club to publicize our policies. I argued for total reform of the rating system to take into account individual ability to pay, and suggested the transfer of teachers’ salaries and better interim relief as ways to achieve this. It was a good time of the year – a slack period for news – to unveil new proposals, and we gained some favourable publicity.

It seemed to me that this proved that we could fight a successful campaign without being more specific; indeed, looking back, I can see that we were already a good deal too specific because, as I was to discover fifteen years later, such measures as transferring the cost of services from local to central government do not in themselves lead to lower local authority rates.

I had hoped to have a pleasant family holiday at Lamberhurst away from the demands of politics. It was not to be. The telephone kept ringing, with Ted and others urging me to give more thought to new schemes. Then I was called back for another meeting on Friday 16 August. Ted, Robert Carr, Jim Prior, Willie Whitelaw and Michael Wolff from Central Office were all there. It was soon clear what the purpose was – to bludgeon me into accepting a commitment in the manifesto to abolish the rates altogether within the lifetime of a Parliament. I argued against this for very much the same reason that I argued against the ‘9½ per cent’ pledge on the mortgage rate. But so shell-shocked by their unexpected defeat in February were Ted and his inner circle that in their desire for reelection they were clutching at straws, or what in the jargon were described as manifesto ‘nuggets’.

There were various ways to raise revenue for expenditure on local purposes. We were all uneasy about moving to a system whereby central government just provided block grants to local government. So I had told Shadow Cabinet that I thought a reformed property tax seemed to be the least painful option. But in the back of my mind I had the additional idea of supplementing the property tax with a locally collected tax on petrol. Of course, there were plenty of objections to both, but at least they were better than putting up income tax.

What mattered to my colleagues was clearly the pledge to abolish the rates, and at Wilton Street Ted insisted on it. I felt bruised and resentful to be bounced again into policies which had not been properly thought out. But I thought that if I combined caution on the details with as much presentational bravura as I could muster I could make our rates and housing policies into vote-winners for the Party. This I now concentrated my mind on doing.

It was at a press conference on the afternoon of Wednesday 28 August that I delivered the package of measures – built around 9½ per cent mortgages and the abolition of the rates – without a scintilla of doubt, which as veteran Evening Standard reporter Robert Carvel said, ‘went down with hardened reporters almost as well as the sherry’ served by Central Office. We dominated the news. It was by general consent the best fillip the Party had had since losing the February election. The Building Societies’ Association welcomed the proposals for 9½ per cent mortgages but questioned my figures about the cost. As I indignantly told them, it was their sums which were wrong and they subsequently retracted. Some on the economic right were understandably critical, but among the grassroots Conservatives that we had to win back the mortgage proposal was extremely popular. So too was the pledge on the rates. The Labour Party was rattled and unusually the party-giving Tony Crosland was provoked into describing the proposals as ‘Margaret’s midsummer madness’. All this publicity was good for me personally as well. Although I was not to know it at the time, this period up to and during the October 1974 election campaign allowed me to make a favourable impact on Conservatives in the country and in Parliament without which my future career would doubtless have been very different.

Although it was my responsibilities as Environment spokesman which took up most of my time and energy, from late June I had become part of another enterprise which would have profound consequences for the Conservative Party, for the country and for me. The setting up of the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) is really part of Keith Joseph’s story rather than mine. Keith had emerged from the wreckage of the Heath Government determined on the need to rethink our policies from first principles. If this was to be done, Keith was the ideal man to do it. He had the intellect, the integrity and not least the humility required. He had a deep interest in both economic and social policy. He had long experience of government. He had an extraordinary ability to form relationships of friendship and respect with a wide range of characters with different viewpoints and backgrounds. Although he could, when he felt strongly, speak passionately and persuasively, it was as a listener that he excelled. Moreover, Keith never listened passively. He probed arguments and assertions and scribbled notes which you knew he would go home to ponder. He was so impressive because his intellectual self-confidence was the fruit of continual self-questioning. His bravery in adopting unpopular positions before a hostile audience evoked the admiration of his friends, because we all knew that he was naturally shy and even timid. He was almost too good a man for politics – except that without a few good men politics would be intolerable.

I could not have become Leader of the Opposition, or achieved what I did as Prime Minister, without Keith. But nor, it is fair to say, could Keith have achieved what he did without the Centre for Policy Studies and Alfred Sherman. Apart from the fact of their being Jewish, Alfred and Keith had little in common, and until one saw how effectively they worked together it was difficult to believe that they could co-operate at all.

Alfred had his own kind of brilliance. He brought his convert’s zeal (as an ex-communist), his breadth of reading and his skills as a ruthless polemicist to the task of plotting out a new kind of free market Conservatism. He was more interested, it seemed to me, in the philosophy behind policies than the policies themselves. He was better at pulling apart sloppily constructed arguments than at devising original proposals. But the force and clarity of his mind, and his complete disregard for other people’s feelings or opinion of him, made him a formidable complement and contrast to Keith. Alfred helped Keith to turn the Centre for Policy Studies into the powerhouse of alternative Conservative thinking on economic and social matters.

I was not involved at the beginning, though I gathered from Keith that he was thinking hard about how to turn his Shadow Cabinet responsibilities for research on policy into constructive channels. In March Keith had won Ted’s approval for the setting up of a research unit to make comparative studies with other European economies, particularly the so-called ‘social market economy’ as practised in West Germany. Ted had Adam Ridley put on the board of directors of the CPS (Adam acted as his economic adviser from within the Conservative Research Department), but otherwise Keith was left very much to his own devices. Nigel Vinson, a successful entrepreneur with strong free enterprise convictions, was made responsible for acquiring a home for the Centre, which was found in Wilfred Street, close to Victoria. It was at the end of May 1974 that I first became directly involved with the CPS. Whether Keith ever considered asking any other members of the Shadow Cabinet to join him at the Centre I do not know: if he had, they certainly did not accept. His was a risky, exposed position, and the fear of provoking the wrath of Ted and the derision of left-wing commentators was a powerful disincentive. But I jumped at the chance to become Keith’s Vice-Chairman.

The CPS was the least bureaucratic of institutions. Alfred Sherman has caught the feel of it by saying that it was an ‘animator, agent of change, and political enzyme’. The original proposed social market approach did not prove particularly fruitful and was eventually quietly forgotten, though a pamphlet called Why Britain Needs a Social Market Economy was published.

What the Centre then developed was the drive to expose the follies and self-defeating consequences of government intervention. It continued to engage the political argument in open debate at the highest intellectual level. The objective was to effect change – change in the climate of opinion and so in the limits of the ‘possible’. In order to do this, it had to employ another of Alfred’s phrases, to ‘think the unthinkable’. It was not long before more than a few feathers began to be ruffled by that approach.

Keith had decided that he would make a series of speeches over the summer and autumn of 1974 in which he would set out the alternative analysis of what had gone wrong and what should be done. The first of these, which was also intended to attract interest among potential fundraisers, was delivered at Upminster on Saturday 22 June. Alfred was the main draftsman. But as with all Keith’s speeches – except the fateful Edgbaston speech which I shall describe shortly – he circulated endless drafts for comment. All the observations received were carefully considered and the language pared down to remove every surplus word. Keith’s speeches always put rigour of analysis and exactitude of language above style, but taken as a whole they managed to be powerful rhetorical instruments as well.

The Upminster speech infuriated Ted and the Party establishment because Keith lumped in together the mistakes of Conservative and Labour Governments, talking about the ‘thirty years of socialistic fashions’. He said bluntly that the public sector had been ‘draining away the wealth created by the private sector’, and challenged the value of public ‘investment’ in tourism and the expansion of the universities. He condemned the socialist vendetta against profits and noted the damage done by rent controls and council housing to labour mobility. Finally – and, in the eyes of the advocates of consensus, unforgivably – he talked about the ‘inherent contradictions [of the] … mixed economy’. It was a short speech but it had a mighty impact, not least because people knew that there was more to come.

From Keith and Alfred I learned a great deal. I renewed my reading of the seminal works of liberal economics and conservative thought. I also regularly attended lunches at the Institute of Economic Affairs where Ralph Harris, Arthur Seldon, Alan Walters and others – in other words all those who had been right when we in government had gone so badly wrong – were busy marking out a new non-socialist economic and social path for Britain. I lunched from time to time with Professor Douglas Hague, the economist, who would later act as one of my unofficial economic advisers.